The Man Who Laughs (1928 film)

The Man Who Laughs is a 1928 American silent romantic drama film directed by the German Expressionist filmmaker Paul Leni. The film is an adaptation of Victor Hugo's 1869 novel of the same name and stars Mary Philbin as the blind Dea and Conrad Veidt as Gwynplaine. The film is known for the grim carnival freak-like grin on the character Gwynplaine's face, which often leads it to be classified as a horror film.[1] Film critic Roger Ebert stated, "The Man Who Laughs is a melodrama, at times even a swashbuckler, but so steeped in Expressionist gloom that it plays like a horror film."[2]

| The Man Who Laughs | |

|---|---|

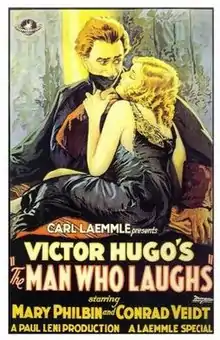

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Paul Leni |

| Produced by | Paul Kohner |

| Screenplay by | J. Grubb Alexander Walter Anthony Mary McLean Charles E. Whittaker |

| Based on | The Man Who Laughs by Victor Hugo |

| Starring | Mary Philbin Conrad Veidt Brandon Hurst Olga V. Baklanova Cesare Gravina Stuart Holmes Samuel de Grasse George Siegmann Josephine Crowell |

| Music by | Ernö Rapée Walter Hirsch Lew Pollack William Axt Sam Perry Gustav Borch |

| Cinematography | Gilbert Warrenton |

| Edited by | Edward L. Cahn Maurice Pivar |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 110 minutes (10 reels) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | Silent English intertitles |

The Man Who Laughs is a Romantic melodrama, similar to films such as The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923). The film was one of the early Universal Pictures productions that made the transition from silent films to sound films, using the Movietone sound system introduced by William Fox. The film was completed in April 1927 but was held for release in April 1928, with sound effects and a music score that included the song, "When Love Comes Stealing", by Walter Hirsch, Lew Pollack, and Ernö Rapée.

Plot

In 1680s England, King James II sentences his political enemy, Lord Clancharlie, to death in an iron maiden. Clancharlie's son, Gwynplaine, is disfigured with a permanent grin by comprachico Dr. Hardquannone, so that he will "laugh forever at his fool of a father". When the comprachicos are exiled, Gwynplaine is deserted in the snow. He discovers a blind baby girl, Dea, whose mother has died of hypothermia. Together, they are taken in by the mountebank Ursus.

Years later, a now-adult Gwynplaine has become the Laughing Man, the freak show star of a traveling carnival. He and Dea have also fallen in love; he remains distant, believing himself unworthy of her affection due to his disfigurement, although she cannot see it. Meanwhile, the jester Barkilphedro, who had been involved in Lord Clancharlie's execution, is now attached to the court of Queen Anne. He discovers records that reveal Gwynplaine's lineage and rightful inheritance. That estate is currently possessed by sexually aggressive vamp Duchess Josiana.

On an evening of Gwynplaine's show performance, Josiana attends, but does not laugh with the rest of the crowd, as she is attracted to Gwynplaine's disfigurement. After the show, she requests his presence to her room that night and attempts to seduce him, but he rejects her advances and flees. He returns to Dea and lets her touch his disfigured face. She accepts him by saying: "God closed my eyes so I could see only the real Gwynplaine!", and the couple express their love for one another. Later the queen's guards arrest Gwynplaine and, to stop his friends from looking for him, they fake his death, leaving Dea, Ursus and his friends heartbroken. Then, the group are ordered to leave England by Barkilphedro.

Queen Anne grants Gwynplaine his peerage and a seat in the House of Lords, and orders Josiana to marry him, in order to restore the proper ownership of the estate. Ultimately, Gwynplaine renounces his title, and refuses the Queen's order of marriage. He escapes, pursued by guards in a chase punctuated by swordplay. He arrives at the docks and is happily reunited with Dea and Ursus on their ship. Together, they all sail away from England.

The film is thus given a more upbeat ending than that of Hugo's novel, in which both Dea and Gwynplaine die at the end.

Cast

- Mary Philbin as Dea

- Conrad Veidt as Gwynplaine

- Brandon Hurst as Barkilphedro

- Julius Molnar Jr. as Gwynplaine (child)

- Olga Vladimirovna Baklanova as Duchess Josiana

- Cesare Gravina as Ursus

- Stuart Holmes as Lord Dirry-Moir

- Samuel de Grasse as King James II Stuart

- George Siegmann as Dr. Hardquanonne

- Josephine Crowell as Queen Anne Stuart

Veidt plays a dual role as Gwynplaine's father, Lord Clancharlie.[3] Many significant silent-era actors appeared in minor or uncredited roles, including D'Arcy Corrigan,[4] Torben Meyer, Edgar Norton, Nick De Ruiz, Frank Puglia, and Charles Puffy.[5] The animal actor used for the role of Homo the Wolf was a dog named Zimbo.[6]

Production

-Gwynplaine.png.webp)

Following the success of Universal Pictures's 1923 adaptation of Victor Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, the company was eager to release another film starring Lon Chaney. A treatment adapting The Phantom of the Opera was prepared, but rejected by the Universal executives. In its place, Chaney was offered the lead in a film version of Hugo's The Man Who Laughs, to be produced under its French title (L'Homme Qui Rit) out of perceived similarity to Les Misérables.[7] The Man Who Laughs, published in 1869, had been subject to significant criticism in both England and France, and was one of Hugo's least successful novels,[8] but it had been filmed twice before. Pathé had produced L'Homme qui rit in France in 1908, and the Austrian film company Olympic-Film released a low-budget German version in 1921 as Das grinsende Gesicht.[9]

Despite Chaney's contract, production did not begin. Universal had failed to acquire film rights to the Hugo novel from the French studio Société Générale des Films. Chaney's contract was amended, releasing him from The Man Who Laughs, but permitting him to name the replacement film, ultimately resulting in the 1925 The Phantom of the Opera.[10] After the success of Phantom, studio chief Carl Laemmle returned to The Man Who Laughs for Universal's next Gothic film "super-production".[11][12] Laemmle selected two fellow expatriate Germans for the project. Director Paul Leni had been hired by Universal following his internationally acclaimed Waxworks,[13] and had already proven himself to the company with The Cat and the Canary.[14] Countryman Conrad Veidt was cast in the Gwynplaine role that was previously intended for Chaney. Veidt had worked with Leni for Waxworks and several other German films, and was well known for his role as Cesare in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.[15][16] American actress Mary Philbin, who had played Christine Daaé opposite Chaney in Phantom, was cast as Dea.[3]

Leni was provided with a skilled crew. Charles D. Hall was chosen to design the sets. He had previously adapted Ben Carré's stage sets to film for Phantom and had worked with Leni for The Cat and the Canary.[16] Jack Pierce became the head makeup artist at Universal in 1926, and was responsible for crafting Gwynplaine's appearance.[16]

During the sequence where Gwynplaine is presented to the House of Lords, the extras were so moved by Veidt's performance that they burst into applause.[17]

Universal put over $1,000,000 into The Man Who Laughs, an extremely high budget for an American film of the time.[18]

Music and sound

Films of the silent era were typically projected with musical accompaniment. Originally, the accompanying music varied not only by film but by venue, and often featured the performance of a live pianist or even, in larger theaters, a full orchestra. The first 30 years of the 20th century also saw the development of the photoplayer and the theatre organ, specialized instruments designed specifically for in-theater entertainment and to accompany silent film, which were installed in hundreds of theaters between 1900–1930, and which eventually usurped the solo pianist and orchestras in most places. But even up until the introduction of sound film, music was substandard or absent entirely in some locations.[19] By the late 1920s, the major film studios had largely shifted to recorded music, synchronized with the film, and distributed along with it.[20]

The Man Who Laughs was initially released without music, but following the film's initial success, it was recalled and re-released with sound effects, a synchronized score, and a theme song,[21] provided by the Movietone sound-on-film system.[22] Leni did not employ the shrieking and creaking sound effects of horror theater (although he did in his following film, The Last Warning). Instead, the film's viewers are disconcerted by hearing the sounds of the crowds and audiences within the film (often laughing at or jeering Gwynplaine), while the main characters (including Gwynplaine himself) are left entirely silent.[23] The film's theme song, "When Love Comes Stealing", was an Ernö Rapée instrumental piece previously used for some showings of the 1922 film Robin Hood, but with added lyrics by Walter Hirsch and Lew Pollack.[24] The remainder of the score comprises music by William Axt, Sam Perry, and Rapée,[25] and one piece by Gustav Borch, which was later reused in the 1932 zombie film White Zombie.[26]

Some of the score, such as the fast-paced melodramatic music used for the chase scene near the end of the film, contrasts sharply with the romantic "When Love Comes Stealing". This effect, although jarring, was probably intentional in order to make the theme song more memorable and encourage sheet music sales.[12][27]

Release

Theatrical release

The film premiered April 27, 1928, in New York, with two showings per day at the Central Theatre. Proceeds from opening night were donated to the American Friends of Blérancourt, a humanitarian aid organization.[28] According to Universal's house organ, The Gold Mine, these limited showings continued at least into May.[29] Also in May, the film had its London premiere, at a trade show at the London Pavilion Theatre on the 2nd.[30]

Home media

For many years, the film was not publicly available. In the 1960s, The Man Who Laughs was among the films preserved by the Library of Congress following a donation from the American Film Institute; along with 22 other such films, it was shown at the New York Film Festival in 1969.[31] It was again screened by Peter Bogdanovich at the Telluride Film Festival in 1998,[32] but remained largely unavailable until Kino International and the Cineteca di Bologna produced a restored version of the film made from two American prints and an Italian print.[33][34] This restoration was released on DVD by Kino on September 30, 2003.[34] Slant Magazine gave this DVD 3.5 out of 5 stars, citing the overall quality of the restoration and the uniqueness of the included extras, including a home movie of Veidt.[33] Kino included this DVD in their five-volume American Silent Horror Collection box set on October 9, 2007.[35] Sunrise Silents also produced a DVD of the film, edited to a slightly longer runtime than the Kino restoration, released in October 2004.[34]

The Man Who Laughs was released on Blu-ray on June 4, 2019, sourced from a new 4K restoration, and features a score performed by the Berklee College of Music.[36]

Critical reception

Contemporary

Initially, the critical assessment of The Man Who Laughs was mediocre, with some critics disliking the morbidity of the subject matter and others complaining that the Germanic looking sets did not evoke 17th-century England.[12]

Paul Rotha was particularly critical. In his 1930 history of film, The Film Till Now, he called The Man Who Laughs a "travesty of cinematic methods",[37] and declared that in directing it, Leni "became slack, drivelling, slovenly, and lost all sense of decoration, cinema, and artistry".[38] The New York Times gave the film a slightly positive review, calling it "gruesome but interesting, and one of the few samples of pictorial work in which there is no handsome leading man".[39]

Modern

As late as the 1970s, critical assessment of the film was largely negative. Writing for Film Quarterly after the New York Film Festival showing, Richard Koszarski described it as "overblown" and a "stylistic mishmash".[31]

In recent times, the assessment has been more positive. Critic Roger Ebert gave the film 4 out of 4 stars, declaring it "one of the final treasures of German silent Expressionism."[2] Film critic Leonard Maltin awarded the film 3 out of a possible 4 stars, stating that the film was "visually dazzling".[40] Kevin Thomas from the Los Angeles Times praised the film, declaring it to be director Leni's masterpiece, writing "In Leni it found its perfect director, for his bravura Expressionist style lifts this tempestuous tale above the level of tear-jerker to genuinely stirring experience."[41] Dennis Schwartz of Ozus' World Movie Reviews rated the film a grade A, praising Veidt's performance as "one of cinema's most sensitive and moving performances".[42] Eric Henderson from Slant Magazine gave the film 3.5 out of 4 stars, offering similar praise towards Veidt's performance, as well as the film's cinematography.[43]

It is among the films with a 100% rating at review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes based on 20 reviews, with a weighted average rating of 8.40/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "A meeting of brilliant creative minds, The Man Who Laughs serves as a stellar showcase for the talents of director Paul Leni and star Conrad Veidt."[44]

Legacy

The Man Who Laughs had considerable influence on the later Universal Classic Monsters films.[45] Pierce continued to provide the makeup for Universal's monsters; comparisons to Gwynplaine's grin was used to advertise The Raven.[46] Hall's set design for The Man Who Laughs helped him develop the blend of Gothic and expressionist features he employed for some of the most important Universal horror films of the 1930s: Dracula, Frankenstein, The Old Dark House, The Invisible Man, The Black Cat, and Bride of Frankenstein.[47] Decades later, the themes and style of The Man Who Laughs were influences on Brian De Palma's 2006 The Black Dahlia, which incorporates some footage from the 1928 film.[48]

.jpg.webp)

The Joker, nemesis to DC Comics's Batman, owes his appearance to Veidt's portrayal of Gwynplaine in The Man Who Laughs. Although Bill Finger, Bob Kane, and Jerry Robinson disagreed as their respective roles in the 1940 creation of the Joker, they agreed that his exaggerated smile was influenced by a photograph of Veidt from the film.[49] Heath Ledger's portrayal of the character in the 2008 film The Dark Knight (which was released 80 years later) makes this connection even more direct by depicting the Joker's smile as the result of disfiguring scarring rather than an expression of his insanity.[50] A 2005 graphic novel exploring the first encounter between Batman and the Joker was also titled Batman: The Man Who Laughs in homage to the 1928 film, as was the Batman Who Laughs, an alternate universe Batman who becomes more like Joker after managing to kill his enemy.[50]

Later adaptations

Although prominent actors, including Christopher Lee and Kirk Douglas, expressed interest in taking the role of Gwynplaine in a hypothetical remake,[9] there has been no American film adaptation of The Man Who Laughs in the sound era; however, there have been three adaptations by European directors. Italian director Sergio Corbucci's 1966 version, L'Uomo che ride (released in the United States as The Man Who Laughs, but in France as L'Imposture des Borgia)[51] substantially altered the plot and setting, placing the events in Italy and replacing the court of King James II with that of the House of Borgia.[9] Jean Kerchbron directed a three-part French television film adaptation, L'Homme qui rit, in 1971. Philippe Bouclet and Delphine Desyeux star as Gwynplaine and Dea; Philippe Clay appeared as Barkilphedro.[51] Jean-Pierre Améris directed another French-language version, also called L'Homme qui rit, which was released in 2012. It stars Marc-André Grondin and Christa Théret, with Gérard Depardieu as Ursus.[52]

Horror-film historian Wheeler Winston Dixon described the 1961 film Mr. Sardonicus, also featuring a character with a horrifying grin, as "The Man Who Laughs ... remade, after a fashion".[53] However, its director, William Castle, has stated the film is an adaptation of "Sardonicus", an unrelated short story by Ray Russell originally appearing in Playboy.[54]

References

Bibliography

- Altman, Rick (2007). Silent Film Sound. Film and Culture. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11663-3.

- Castle, William (1992) [1976]. Step Right Up! I'm Gonna Scare the Pants Off America: Memoirs of a B-Movie Mogul. Putnam. ISBN 978-0-88687-657-9.

- Conrich, Ian (2004). "Before Sound: Universal, Silent Cinema, and the Last of the Horror-Spectaculars". In Prince, Stephen (ed.). The Horror Film. Rutgers University Press. pp. 40–57. ISBN 978-0-8135-3363-6.

- DiLeo, John (2007). Screen Savers: 40 Remarkable Movies Awaiting Rediscovery. Hansen. ISBN 978-1-60182-654-1.

- Dixon, Wheeler Winston (2010). A History of Horror. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4795-4.

- Gleizes, Delphine, ed. (2005). L'œuvre de Victor Hugo à l'écran (in French). L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-7475-9094-5.

- Holston, Kim R. (2013). Movie Roadshows: A History and Filmography of Reserved-Seat Limited Showings, 1911–1973. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6062-5.

- Josephson, Matthew (2005) [1942]. Victor Hugo: A Realistic Biography of the Great Romantic. Jorge Pinto Books. ISBN 978-0-9742615-7-7.

- Long, Harry H (2012). "The Man Who Laughs". In Soister, John T.; Nicolella, Henry; Joyce, Stever; Long, Harry H; Chase, Bill (eds.). American Silent Horror, Science Fiction and Fantasy Feature Films, 1913–1929. McFarland. pp. 374–378. ISBN 978-0-7864-3581-4.

- Mank, Gregory William (2009) [1990]. Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff: The Expanded Story of a Haunting Collaboration, with a Complete Filmography of Their Films Together (revised ed.). McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3480-0.

- Melnick, Ross (2012). American Showman: Samuel 'Roxy' Rothafel and the Birth of the Entertainment Industry, 1908–1935. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-15904-3.

- Richards, Rashna Wadia (2013). Cinematic Flashes: Cinephilia and Classical Hollywood. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-00688-2.

- Riley, Philip J. (1996). The Phantom of the Opera. Hollywood Archives Series. Magicimage Filmbooks. ISBN 978-1-882127-33-7.

- Rotha, Paul (1930). The Film Till Now: A Survey of the Cinema. Jonathan Cape. OCLC 886633324.

- Slowik, Michael (2014). After the Silents: Hollywood Film Music in the Early Sound Era, 1926–1934. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-16582-2.

- Soister, John T. (2002). Conrad Veidt on Screen: A Comprehensive Illustrated Filmography. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4511-0.

- Solomon, Matthew (2013). "Laughing Silently". In Pomerance, Murray (ed.). The Last Laugh: Strange Humors of Cinema. Wayne State University Press. pp. 15–30. ISBN 978-0-8143-3513-0.

- Stephens, Michael L. (1998). Art Directors in Cinema: A Worldwide Biographical Dictionary. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3771-9.

Notes

- PopMatters Staff. "PopMatters: The Man Who Laughs". popmatters.com. Retrieved January 11, 2007.

- Roger Ebert. "Roger Ebert: Great Movies: The Man Who Laughs (1928)". rogerebert.com. Retrieved January 11, 2007.

- Soister 2002, p. 206.

- Long 2012, p. 313.

- Long 2012, p. 374.

- IMDb. "Zimbo the Dog, Actor".

- Riley 1996, pp. 39–40.

- Josephson 2005, p. 459.

- Long 2012, p. 378.

- Riley 1996, p. 40.

- Solomon 2013, p. 27.

- Newman, James (October 24, 2003). "The Man Who Laughs". Images. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- Stephens 1998, p. 196.

- DiLeo 2007, pp. 176–177.

- DiLeo 2007, p. 176.

- Conrich 2004, p. 42.

- "Gossip of All the Studios". Photoplay. February 1928. Vol. XXXIII. No. 3. p. 88.

- Phil M. Daly (April 22, 1928). "And That's That". lantern.mediahist.org. The Film Daily. XLIV (19): 5. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- Altman 2007, pp. 199–200.

- Slowik 2014, pp. 41–42.

- Soister 2002, pp. 202–210.

- "The Man Who Laughs". Catalogue of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- Richards 2013, pp. 64–66.

- Melnick 2012, p. 479.

- Holston 2013, p. 304.

- Long 2012, p. 377.

- Slowik 2014, p. 323.

- Holston 2013, p. 64.

- "'Man Who Laughs' Captures London as It Did N.Y.". The Gold Mine. 2 (18): 2. 1928.

- Soister 2002, p. 205.

- Koszarski, Richard (1969–1970). "Lost Films from the National Film Collection". Film Quarterly. 23 (2): 31–37. doi:10.2307/1210519. JSTOR 1210519.

- Ebert, Roger (January 18, 2004). "The Man Who Laughs". RogerEbert.com. Great Movies. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- Henderson, Eric (September 29, 2003). "The Man Who Laughs". Slant Magazine. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- "The Man Who Laughs". Silent Era. Silent Era Films on Home Video. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- "American Silent Horror Collection". Silent Era. Silent Era Films on Home Video. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- Review. Blu-ray.com. June 20, 2019.

- Rotha 1930, p. 204.

- Rotha 1930, p. 31.

- "The Screen; His Grim Grin". New York Times.com. The New York Times. April 28, 1928. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- Leonard Maltin; Spencer Green; Rob Edelman (2010). Leonard Maltin's Classic Movie Guide. Plume. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-452-29577-3.

- Thomas, Kevin (August 15, 1994). "Leni's 'Man Who Laughs' a Silent, Stirring Experience". LA Times.com. Kevin Thomas. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- Schwartz, Dennis. "manwholaughs". Sover.net. Dennis Schwartz. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- Henderson, Eric. "The Man Who Laughs". Slant Magazine.com. Eric Henderson. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- "The Man Who Laughs (1928)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- DiLeo 2007, p. 177.

- Mank 2009, p. 256.

- Stephens 1998, pp. 148–150, 196.

- Uhlich, Keith (September 11, 2006). "The Black Dahlia". Slant Magazine. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- Rodriguez, Mario (2014). "Physiognomy and Freakery: The Joker on Film". Americana. 13 (2).

- Serafino, Jay (August 3, 2016). "How a 1928 Silent Film Influenced the Creation of the Joker". Mental Floss. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- Gleizes 2005, p. 244.

- Young, Neil (September 12, 2012). "The Man Who Laughs (L'Homme Qui Rit): Venice Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- Dixon 2010, p. 21.

- Castle 1992, p. 163.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Man Who Laughs (1928 film) |