The Man Who Would Be King

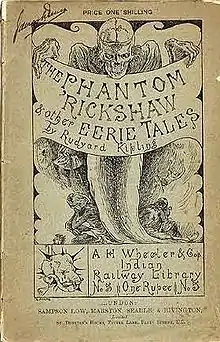

"The Man Who Would Be King" (1888) is a story by Rudyard Kipling about two British adventurers in British India who become kings of Kafiristan, a remote part of Afghanistan. The story was first published in The Phantom Rickshaw and other Eerie Tales (1888).[1] It also appeared in Wee Willie Winkie and Other Child Stories (1895), and numerous later editions of that collection. It has been adapted for other media a number of times.

| "The Man Who Would Be King" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Author | Rudyard Kipling |

| Country | United Kingdom, British India |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Adventure |

| Published in | The Phantom 'Rickshaw and other Eerie Tales |

| Publication type | Anthology |

| Publisher | A. H. Wheeler & Co. of Allahabad |

| Publication date | 1888 |

Plot summary

The narrator of the story is an Indian journalist in 19th century India—Kipling himself, in all but name. Whilst on a tour of some Indian native states he meets two scruffy adventurers, Daniel Dravot and Peachey Carnehan. Softened by their stories, he agrees to help them in a minor errand, but later he regrets this and informs the authorities about them—preventing them from blackmailing a minor rajah. A few months later the pair appear at his newspaper office in Lahore. They tell him of a plan they have hatched. They declare that after years of trying their hands at all manner of things, they have decided that "India is not big enough for them". They plan to go to Kafiristan and set themselves up as kings. Dravot will pass as a native and, armed with twenty Martini-Henry rifles, they plan to find a king or chief to help him defeat enemies. Once that is done, they will take over for themselves. They ask the narrator for the use of books, encyclopedias and maps of the area—as a favour, because they are fellow Freemasons, and because he spoiled their blackmail scheme. They also show him a contract they have drawn up between themselves which swears loyalty between the pair and total abstinence from women and alcohol.

Two years later, on a scorching hot summer night, Carnehan creeps into the narrator's office. He is a broken man, a crippled beggar clad in rags and he tells an amazing story. Dravot and Carnehan succeeded in becoming kings: traversing treacherous mountains, finding the Kafirs, mustering an army, taking over villages, and dreaming of building a unified nation and even an empire. The Kafirs (pagans, not Muslims) were impressed by the rifles and Dravot's lack of fear of their idols, and acclaimed him as a god, the reincarnation or descendant of Alexander the Great. They show a whiter complexion than others of the area ("so hairy and white and fair it was just shaking hands with old friends") implying their ancient lineage to Alexander himself. The Kafirs practised a form of Masonic ritual, and Dravot's reputation was further cemented when he showed knowledge of Masonic secrets that only the oldest priest remembered.

Their schemes were dashed, however, when Dravot (against the advice of Carnehan) decided to marry a Kafir girl. Kingship going to his head, he decided he needed a Queen and then royal children. Terrified at marrying a god, the girl bit Dravot when he tried to kiss her during the wedding ceremony. Seeing him bleed, the priests cried that he was "Neither God nor Devil but a man!" Most of the Kafirs turned against Dravot and Carnehan. A few of his men remained loyal, but the army defected and the two kings were captured.

Dravot, wearing his crown, stood on a rope bridge over a gorge while the Kafirs cut the ropes, and he fell to his death. Carnehan was crucified between two pine trees. When he survived this torture for a whole day, the Kafirs considered it a miracle and let him go. He begged his way back to India.

As proof of his tale, Carnehan shows the narrator Dravot's head, still wearing the golden crown, which he swears never to sell. Carnehan leaves carrying the head. The next day the narrator sees him crawling along the road in the noon sun, with his hat off and gone mad. The narrator sends him to the local asylum. When he inquires two days later, he learns that Carnehan has died of sunstroke. No belongings were found with him.[2]

Acknowledged sources

Kafiristan was recognized as a real place by at least one early Kipling scholar, Arley Munson, who in 1915 called it "a small tract of land in the northeastern part of Afghanistan," though she wrongly thought the "only source of information is the account of the Mahomedan traders who have entered the country."[3] By then, Kafiristan had been literally wiped off the map and renamed "Nuristan" in Amir Abdur Rahman Khan's 1895 conquest, and it was soon forgotten by literary critics who, under the sway of the New Criticism, read the story as an allegory of the British Raj. The disappearance of Kafiristan was so complete that a 1995 New York Times article referred to it as "the mythical, remote kingdom at the center of the Kipling story."[4]

As the New Historicism replaced the New Criticism, scholars rediscovered the story's historical Kafiristan, aided by the trail of sources left in it by Kipling himself, in the form of the publications the narrator supplies to Dravot and Carnehan.

- "Volume INF-KAN of the Encyclopædia Britannica," which (in the ninth edition of 1882) contained Sir Henry Yule's long "Kafiristan" entry.[5] Yule's entry described Kafiristan as "land of lofty mountains, dizzy paths, and hair-rope bridges swinging over torrents, of narrow valleys laboriously terraced, but of wine, milk, and honey rather than of agriculture." He includes Bellew's description of a Kafir informant as "hardly to be distinguished from an Englishman" and comments at length on the reputed beauty of Kafir women.

- "Wood on the Sources of the Oxus," namely, A Personal Narrative of a Journey to the Source of the River Oxus by the Route of the Indus, Kabul, and Badakhshan (1841) by Captain John Wood (1811–1871), from which Dravot extracts route information.[6]

- "The file of the United Services' Institute," accompanied by the directive, "read what Bellew says," refers, no doubt, to an 1879 lecture on "Kafristan [sic] and the Kafirs" by Surgeon Major Henry Walter Bellew (1834–1892). This account, like Wood's, was based largely on second-hand native travellers' accounts and "some brief notices of this people and country scattered about in the works of different native historians," for, as he noted, "up to the present time we have no account of this country and its inhabitants by any European traveler who has himself visited them." The 29-page survey of history, manners and customs, was as "sketchy and inaccurate" as the narrator suggests, Bellew acknowledging that "of the religion of the Kafirs we know very little," but noting that "the Kafir women have a world wide reputation of being very beautiful creatures."[7]

- The narrator smokes "while the men poured over Raverty, Wood, the maps, and the Encyclopædia." Henry George Raverty's "Notes on Káfiristan" appeared in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1859, and it is presumably this work, based on Raverty's contact with some Siah-Posh Kafirs region.[8]

Possible models

In addition to Kipling's acknowledged sources, a number of individuals have been proposed as possible models for the story's main characters.

- Alexander Gardner (1785–1877), American adventurer captured in Afghanistan in 1823. Gardner "stated that he visited Kafiristan twice between 1826 and 1828, and his veracity was vouched for by . . . reliable authorities"[9] "Only Gardner provides the three essential ingredients of the Kipling novel," according to John Keay.[10]

- Josiah Harlan (1799–1871), American adventurer enlisted as a surgeon with the British East India Company's army in 1824.[11]

- Frederick "Pahari" Wilson (1817–1883), an English officer who deserted during the First Afghan War and later became "Raja of Harsil."[12]

- James Brooke, an Englishman who in 1841 was made the first White Rajah of Sarawak in Borneo, in gratitude for military assistance to the Sultan of Brunei. Kipling alludes to Brooke in the story by referring to Kafiristan as the "only one place now in the world that two strong men can Sar-a-whack."

- Adolf Schlagintweit (1829–1857) German botanist and explorer of Central Asia. Suspected of being a Chinese spy, he was beheaded in Kashgar by the amir, Wali Khan.

- William Watts McNair (1849–1889), a surveyor in the Indian Survey Department, who in 1883 visited Kafiristan while on furlough disguised as a hakim or native doctor, disregarding Government regulations.[13] His report to the Royal Geographical Society earned him the Murchison Award.[14]

Reception

- As a young man the would-be poet T. S. Eliot, already an ardent admirer of Kipling, wrote a short story called "The Man Who Was King". Published in 1905 in the Smith Academy Record, a school magazine of the school he was attending as a day-boy, the story explicitly shows how the prospective poet was concerned with his own unique version of the "King".[15][16][17]

- J. M. Barrie described the story as "the most audacious thing in fiction".[18]

- Kingsley Amis called the story a "grossly overrated long tale" in which a "silly prank ends in predictable and thoroughly deserved disaster."[19]

- Additional critical responses are collected in Bloom's Rudyard Kipling.[20]

Adaptations

Literature

- The title of J. Michael Bailey's popular science book, The Man Who Would Be Queen (2003), plays on Kipling's title.

- In Jimmy Buffett's book Salty Piece of Land, the movie version starring Sean Connery and Michael Caine is referenced several times as a significant plot line to the story.

- The two main characters appear in by Ian Edginton's graphic novel Scarlet Traces (2002).

- Garth Nix's short story "Losing Her Divinity", in the book Rags and Bones, is based on the story.

- In H. G. Wells' The Sleeper Awakes (1910), the Sleeper identifies a cylinder ("a modern substitute for books") with "The Man Who Would Be King" written on the side in mutilated English as "oi Man huwdbi Kin". The Sleeper recalls the story as "one of the best stories in the world".[21]

Comic

This story is mentioned in "The Golden House of Samarkand", comic by Hugo Pratt (1967). The hero, Corto Maltese, is on the trail of a treasure hidden by Alexander the Great in Kafiristan.

Radio

- A CBS Radio adaption of the story by Les Crutchfield was broadcast on the anthology series Escape on 7 July 1947. It was rebroadcast on 1 August 1948.

- An adaptation by Mike Walker was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 22 July 2018 as part of the To The Ends of the Earth series.[22]

Films

- The Man Who Would Be King (1975), adapted and directed by John Huston, starring Sean Connery as Dravot and Michael Caine as Carnehan, with Christopher Plummer as Kipling. (As early as 1954, Humphrey Bogart expressed the desire to star in The Man Who Would Be King and was in talks with Huston.)[23]

- The DreamWorks 2D hand-drawn animated movie The Road to El Dorado (2000) is loosely based on the story.

Television

- The 1993 Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode "The Storyteller" was based on the short story, according to Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Companion.

- In the 1990 Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Déjà Q" the omnipotent Q, stripped of his powers and left to live as a mortal human, sarcastically refers to himself as "The king who would be man."

- Supernatural, season 6, episode 20 is titled "The Man Who Would Be King."

Games

- In the video game Borderlands 2, one of the main missions is called "The Man Who Would Be Jack" as a reference to the story.

- In the video game Civilization V, the achievement for completing the game on any difficulty with Alexander the Great is named "The Man Who Would Be King."

- Gold and Glory: The Road to El Dorado was the video game tie-in, developed by Revolution Software, released on PlayStation, Game Boy Color, and Microsoft Windows.[24]

Music

- "The Man Who Would be King" is a song by Dio on the album Master of the Moon.

- "The Man Who Would Be King", a 2004 song written by Pete Doherty and Carl Barât of The Libertines, appears in their self-titled second album. The songwriters are known fans of Kipling and his work. It reflects on the story, as two friends – who seem to be at the top – drift away from each other and begin to despise each other, mirroring the bandmates' turbulent relationship and eventual splitting of the band shortly after the album's release.

- The ninth track on Iron Maiden's 15th studio album, The Final Frontier, is entitled "The Man Who Would Be King". The song has no apparent connection with the novella apart from the title.

- In rapper Billy Woods' album History Will Absolve Me, the third track is called "The Man Who Would Be King"

References

- "The Man Who Would Be King". Indian Railway Library. A. H. Wheeler & Co of Allahabad. 5. 1888.

- "Plot Summary of "The Man Who Would Be King" in Harold Bloom, ed. Rudyard Kipling, Chelsea House, 2004. pp. 18–22.

- Arley Munson, Kipling's India (Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday, Page & Co. 1915): 90.

- Michael Specter, "The World; Meet Stan, and Stan, and . . ." New York Times, 7 May 1995, E:3. cited in Edward Marx, "How We Lost Kafiristan." Representations 67 (Summer 1999): 44.

- Henry Yule, "Kafiristan," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th ed. (London: Henry G. Allen, 1882): 13:820–23.

- John Wood, A Personal Narrative of a Journey to the Source of the River Oxus, by the Route of the Indus, Kabul, and Badakhshan, Performed under the Sanction of the Supreme Government of India, in the Years 1836, 1837, and 1838 (London: J. Murray, 1841)

- Henry Walter Bellew, "Kafristan [sic] and the Kafirs: A Lecture Delivered at the United Service Institution," Journal of the United Service Institution 41 (1879): 1. Bellew was also the author of a number of other works on Afghanistan.

- H.G. Raverty, "Notes on Kafiristan," Journal of the Asiatic Society 4 (1859): 345.

- B. E. M. Gurdon, "Early Explorers of Kafiristan," Himalayan Journal 8:3 (1936): 26

- John Keay, The Tartan Turban: In Search of Alexander Gardner (London: Kashi House, 2017). Keay's ingredients are "the location (Kafiristan), the legend (of the Kafirs having once admitted white strangers) and the detail (of these strangers being two Europeans of whom the Kafirs were somewhat in awe)."

- Macintyre, Ben The Man Who Would Be King, New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2002. Macintyre claimed that "Kipling would certainly have been familiar with Harlan's history, just as he would have known of the even earlier exploits of George Thomas, the eighteenth-century Irish mercenary."

- Robert Hutchison, The Raja of Harsil: The Legend of Fredrick "Pahari Wilson" New Delhi: Roli Books, 2010. "By then Harlan's exploits had been all but forgotten. The exploits of 'Pahari' Wilson, on the other hand, were still vividily remembered... Wilson fits the character far better than Josiah Harlan."

- W.W. McNair, "A Visit to Kafiristan," Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society 6:1 (Jan. 1884): 1–18; reprinted with additional material in J.E. Howard, ed., Memoir of William Watts McNair: The First European Explorer of Kafiristan (London: D.J. Keymer, 1890).

- Edward Marx, "How We Lost Kafiristan." Representations 67 (Summer 1999): 44.

- Narita, Tatsushi & Coutinho, Eduardo F. (Editor) (2009). "Young T. S. Eliot as a Transpacific 'Literary Columbus': Eliot on Kipling's Short Story". Beyond Binarism: Discontinuities and Displacements: Studies in Comparative Literature. Rio de Janeiro: Aeroplano: 230–237.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Narita, Tatsushi (2011). T. S. Eliot and his Youth as 'A Literary Columbus'. Nagoya: Kougaku Shuppan.

- Narita, Tatsushi (1992). "Fiction and Fact in T.S. Eliot's 'The Man Who Was King". Notes and Queries. Pembroke College, Oxford University. 39 (2): 191–192. doi:10.1093/nq/39.2.191-a.

- Norman Page, quoted in John McGivering and George Kieffer, eds., Kipling Society notes.

- Kingsley Amis, Rudyard Kipling (London: Thames and Hudson, 1975), 62, quoted in John McGivering and George Kieffer, eds., Kipling Society notes.

- Bloom, Harold (Editor) (2004). Rudyard Kipling. Chelsea House.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Wells, H. G. & Parringer, Patrick (Editor) (2005). The Sleeper Awakes. England: Penguin Classics. p. 56.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "To the Ends of the Earth: The Man Who Would Be King". BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "bogart-bacall-grace-person-to-person-a-look-back". CBS News. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- "Gold and Glory: The Road to El Dorado". Gamespot. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

Further reading

- Kreitzer, Larry J. (January 2002). The Son of God Goes Forth to War: Biblical Imagery in Rudyard Kipling's 'The Man Who Would Be King'. ISBN 9781841271484.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Full text at Project Gutenberg

The Man Who Would Be King public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Man Who Would Be King public domain audiobook at LibriVox

.jpg.webp)

Schlegel_Julius_btv1b84503133_(cropped).jpg.webp)