The Story of Marie and Julien

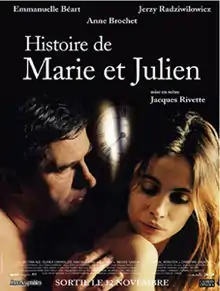

The Story of Marie and Julien (French: Histoire de Marie et Julien) is a 2003 French drama film directed by Nouvelle Vague film maker Jacques Rivette. The film slowly develops from a drama about blackmail into a dark, yet tender, supernatural love story between Marie and Julien, played by Emmanuelle Béart and Jerzy Radziwiłowicz.[3][4][5] Anne Brochet plays the blackmailed Madame X. Béart had previously worked with Rivette in La Belle Noiseuse, as had Radziwiłowicz in Secret Defense. The film was shot by William Lubtchansky, and edited by Nicole Lubtchansky, both frequent collaborators of Rivette's.

| The Story of Marie and Julien | |

|---|---|

French theatrical release poster | |

| French | Histoire de Marie et Julien |

| Directed by | Jacques Rivette |

| Produced by | Martine Marignac |

| Written by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | William Lubtchansky |

| Edited by | Nicole Lubtchansky |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 150 minutes |

| Country |

|

| Language | French |

The film was originally going to be made in 1975 as part of a series of four films, but shooting was abandoned after two days, only to be revisited by Rivette 27 years later. It premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2003 and had a cinema release in France, Belgium and the UK. It was shown in competition at the San Sebastian International Film Festival and was nominated for the Prix Louis-Delluc. Some critics found the film tedious, long, and pretentious, while others maintained that it was moving, intelligent, and among Rivette's best work. The film was frequently compared to other supernatural thrillers, among them Vertigo (1958), The Sixth Sense (1999), and The Others (2001).

Plot

Julien (Radziwiłowicz) is a middle-aged clockmaker who lives alone with his cat in a large house in the Paris suburbs. Julien is blackmailing 'Madame X' (Brochet) who is importing fake antique Chinese silks,[4] and may have murdered her sister.[6] By chance, he meets Marie (Béart), a beautiful young woman he last saw a year ago, and they begin a passionate relationship. Though elusive, Marie agrees to move in with him; she acts strangely at times and appears absent.[7] A mystery connects Marie to Madame X's dead sister and in uncovering Marie's secret Julien risks losing her.[8] The film is separated into four parts, named to reflect the narrative perspective.[2][9]

Julien: Julien dreams of Marie, whom he met just over a year before at a party, and with whom he would have begun a relationship but for them both having partners. He immediately runs into her on the street as she is running for her bus and he is off to meet Madame X.[5][6] They agree to meet again, but Marie fails to appear and he returns home to find Madame X waiting for him against their agreement, so he raises his price tenfold. Madame X returns the next day to try to bargain, and asks for a letter back that he does not have. Marie invites him to her place for dinner, where Julien tells her his girlfriend ran away with another man and Marie says her boyfriend Simon died six months ago. They have sex, but in the morning Marie has checked out of her apartment. Julien returns home to find that his house has been ransacked. He tries to find her by ringing her old boss, then tracks her down when an unknown woman calls to tell him the hotel Marie is staying at. Julien visits her there, and Marie agrees to move in with him.

Julien et Marie: Marie makes herself at home, trying on the clothes of Julien's old girlfriend,[10] exploring the house, and watching him at work. Their lovemaking is passionate,[9] but Marie's behaviour is unusual. She is sometimes cold or trance-like, at one point reciting words in an unidentified language,[11][12] and she is physically detached and unaware of the time — Julien corrects her "bonjour" to "bonsoir".[13] She is jealous of his ex,[14] compulsively decorates and rearranges a room in his attic,[5] feels compelled to act out her dreams,[9] and does not bleed when scratched[11] — something she keeps from Julien. She sees a girl in her dreams who shows her a "forbidden sign" with her hands.[15] Marie helps Julien in his blackmailing, and after meeting Madame X, who only knows of Marie as "l'autre personne",[10] Marie is handed a letter by someone who says she is Madame X's sister (Bettina Kee); she is the girl Marie dreamed of before.

Marie et Julien: The letter is from Madame X's sister Adrienne to Madame X. Julien meets Madame X again, and she tells him her sister killed herself by drowning six months before. He cannot understand who gave Marie the letter, but she insists that her sister left the letter to frame her and although dead she is "reliving" (a revenant)[15] — and Marie is also. Adrienne —who though dead still appears and speaks to her— has told Madame X that Marie is "like me". He thinks she is mad. Julien becomes frustrated at Marie spending so much time alone in the attic. When she finally shows him the room, she says she does not know what it is for. She leaves before Julien wakes and checks into another hotel. He rings Marie's old boss who suggests talking to Marie's friend Delphine; Delphine says that Marie's relationship with Simon drove Marie mad and ended their friendship.

Marie: Julien visits Marie and Simon's old apartment, where the letting agent shows him a room that Julien chillingly recognises — it is identical to the room Marie has prepared. This is where Marie hanged herself, trying to frame Simon in revenge after a terrible row.[5][11] Julien returns home and Marie silently leads him to the attic where she has prepared a noose, feeling she has to hang herself again. Julien carries her downstairs, and they make love again. She leaves to meet Adrienne, who says that she knows that Marie no longer wants to die. They agree they do not know the rules of their situation.[2] Returning, Marie interrupts Julien about to hang himself in a desperate attempt to join her.[11] He runs to the kitchen and tries to slit his wrist; Marie stops him and her wrist and his palm are cut. Marie warns him that he will lose all memory of her, but he says that all he wants is for her to be there. Marie slowly covers her face with her hands — "the forbidden sign" — and Julien becomes oblivious to her and unaware of why he is bleeding.[10] Madame X arrives for her letter and he hands it over, confused by her enquiries about "l'autre personne". Madame X burns the letter, freeing Adrienne. Marie cries while watching Julien sleep, and as her tears land on her wrist her cut bleeds. Julien wakes and asks who she is; she replies that she is "the one he loved". He doubts it as she's "not his type", but she says with a smile to give her a little time.

Cast

- Emmanuelle Béart as Marie Delambre.

- Jerzy Radziwiłowicz as Julien Müller.

- Anne Brochet as Madame X.

- Bettina Kee as Adrienne, the sister of Madame X.

- Olivier Cruveiller as Vincent Lehmann, L'éditeur, Marie's old boss.

- Mathias Jung as Le concierge, the desk clerk at Marie's apartment.

- Nicole Garcia as L'amie, Marie's friend.

Themes and analysis

—Jacques Rivette, director[16]

Like Rivette's earlier film La Belle Noiseuse, the main themes are romantic longing, impermanence, and identity, but this film adds the themes of mortality,[17] chance, and destiny,[6][7] and motifs are repeated from Rivette's Celine and Julie Go Boating.[18] The name of Julien's cat, Nevermore, evokes Poe's The Raven and its similar themes of death and longing.[17] Julien's work as a clockmaker, literally trying to repair time, is an obvious metaphor,[17] and the film is also timeless, giving no indication of when it is set.[18] The blackmail sub-plot is a device to help tell the central love story between Marie and Julien and to explain Marie's situation;[5] Julien is an unlikely blackmailer and Madame X's benevolence towards him is surprising.[8] The plot features dream logic impinging on reality:[19][20][21] Senses of Cinema highlighted the role of "outlandish chance"[9] and Film Comment noted the feeling that the characters are inventing or re-enacting the narrative.[22] Marie may be aware that she is part of a narrative, but she still lacks control over her fate.[9] Michael Atkinson believed that Rivette was working in the "border world between narrative meaning and cinematic artifice".[23]

The emotional distance of the characters and the intellectual and artificial-seeming, quasi-theatrical dialogue is deliberate,[10][17] depicting their simultaneous connection and isolation.[17] The chasm between Marie and Julien, due to his corporeality and her ghostly nature, is emphasised in the contrast between his physical activity and her status as an onlooker.[5] Rivette says he wanted the lovers to appear ill-suited and for the viewer to question the relationship;[16] they love each other passionately yet they are essentially strangers.[17] Béart believes that Marie was more alive than Julien, and that he literally wakes up to her existence only at the very end of the film.[11]

Finally revealed to be a ghost story inspired by nineteenth-century French fantasy literature,[11][18] the film uses the conventions of the genre —that people who die in emotional distress or with an unfinished task may become ghosts— and openly details these conventions. Marie and Adrienne's 'lives' as revenants are reduced to a single purpose, each with only the memory of her suicide and her last emotions remaining.[5] Julien, like the audience, is eventually confronted with Marie's nightmare of repetition.[5][11] Elements of the horror genre are used, not to scare but to explore memory and loss.[24] To stay with Marie, Julien first has to forget about her,[13] and at the end they have the promise of a new beginning.[22] Marie becomes a living person again rather than an object of fantasy.[11] Marie's tears and blood are a miracle overcoming her death, and may reflect a fantasy of turning back the menopause.[11] The credits are accompanied by an upbeat jazz song performed by Blossom Dearie, Our Day Will Come,[9] that represents love as a pledge,[10] the only music used in the film.[8]

There is an aesthetic focus on Béart's body, Julien telling Marie that "I love your neck, your arms, your shoulders, your mouth, your stomach, your eyes - I love everything." The focus is more than erotic as it symbolises Marie's fight for corporeality.[11][17] The film includes Rivette's first ever sex scenes, one of them arranged by Béart. The five candid and emotionally charged sex scenes focus on their upper bodies and faces,[11][17] and on their erotic monologues that employ elements of fairy tale, horror, and sadomasochism.[7][11]

Béart is given an ethereal quality by Lubtchansky's cinematography and lighting,[8] and she subtly portrays Marie's detachment and vulnerability.[7] In the latter part of the film Béart is dressed in grey and looks tired and wan, showing Marie's ageing and angst.[11] Béart says she made deliberate use of silence in playing the part.[25] Radziwiłowicz's performance allows the viewer to sympathise with Julien despite the character's initial dislikeable nature.[17] Brochet as Madame X has a cool ease and grace.[10]

Production

Original shoot

Rivette originally began to make Marie et Julien, as it was then titled, in 1975 with producer Stéphane Tchalgadjieff as part of a series of four films he first called Les filles du feu and later Scènes de la Vie Parallele.[26][27] Rivette said in 2003 that the film was based on the true story of a woman who committed suicide.[28] He first shot Duelle (fr:Duelle) in March–April and Noroît (fr:Noroît) in May, although the latter was not released, and the fourth film, a musical comedy meant to star Anna Karina and Jean Marais, was never shot. Filming began on Marie et Julien that August, with Albert Finney and Leslie Caron in the lead roles and Brigitte Rouan as Madame X,[29] but after two days Rivette gave up filming due to nervous exhaustion.[16] He later used the names of the lovers, Marie and Julien, in his 1981 film Le Pont du Nord.[30][31]

Revisiting the screenplay

After Rivette had later success with La Belle Noiseuse and Va Savoir in the 1990s, he revisited his older unproduced screenplays. With Hélène Frappat, he published in book form three of his "phantom films" including Marie et Julien in 2002.[29][32] He decided to film Marie et Julien; a script had never been written and the footage had been lost, but cryptic notes by his assistant Claire Denis that had been kept by Lubtchansky (who had also been cinematographer in 1975) were enough to work from.[16][33] The original screenplay included a speaking "polyglot cat", characters whose names change, a "suicide room" similar to The Seventh Victim, "Madame X", and an unknown "forbidden gesture" that the notes stated: "Do not forget".[34]

Filming

Rivette worked with scriptwriters Pascal Bonitzer and Christine Laurent using an automatic writing approach that involved writing the script day by day; the actors and filmmakers did not know the direction of the story in advance of each day's filming.[35] Eurimages provided €420,000 of funding in July 2002,[36] and the film was shot that autumn and winter.[29] Rivette immediately thought of Béart, who starred in La Belle Noiseuse, to play the carnal Marie.[16] Béart has said that "Of all the films I've made, this was the one which most disturbed people very close to me. They said: 'It's almost as though the Emmanuelle we know was up there on the screen.'."[25] Béart's image in the media at the time was characterised by the near hysteria seen when she appeared naked on the cover of Elle in May 2003 after filming ended.[11]

Direction

The film illustrates Rivette's view that the act of watching cinema involves game-playing, day-dreaming and paranoid fantasy.[4] He leaves aside the usual devices of the horror genre—no music, shock sound effects, special effects, or gore—evoking feelings and scenes verbally rather than showing them,[11] yet he does employ Hitchcockian "MacGuffins" such as chance encounters, "clues," and the blackmail plot-line.[22] The use of oneiric visuals in the opening and closing scenes of the film was influenced by Rivette's earlier film Hurlevent (1985), an adaptation of Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë.[37] Some of the dialogue that was in the original notes was read as though quoting.[38]

Film critic Glenn Kenny has said that the "calm precision" of the mise en scène in the opening dream sequence "put [him] under such a powerful spell" that "it reconfirmed ... Rivette's standing as an ultimately unquantifiable master".[21] Throughout the film, everyday sounds are amplified by a lack of music, and the film uses sweeping long shots,[2] and several incidental scenes of Julien working, talking with his cat,[8] and of the characters sleeping.[4] Slant Magazine commented that the cat is the film's most interesting character,[39] and Philippa Hawker of The Age notes that the film "has one of the best sequences involving a cat on film."[19] The camera follows the cat and films it looking directly at the camera, giving a sense of artistic freedom and spontaneity.[9]

The cinematography by William Lubtchansky furthers Rivette's interest in visual textures. The film's colour palette is largely natural, except for certain scenes—like the initial dream sequence—that are filmed in vivid colours.[17] In the scene where Marie is arranging the attic room, the light changes—from shadow to warm light—just as she places an oil lamp on a stool to indicate that she has placed it correctly; this introduces a supernatural element that contrasts with the realism of the rest of the film.[40][41]

Reception

Critics' responses were mixed: some found the film evocative and powerful, whereas others saw it as slow and frustrating. Guy Austin writing in Scope noted that "bodily reactions are not part of critical reactions to [the film]. In both press and online, the head governs the body in reactions to Rivette."[11] Rivette had said before the release that "This I know in advance – whether it is good or not, some people will love it and others will hate it."[37]

A: "You always wish there were more of a response. But often it comes five, ten years down the road. As it turns out, for Marie et Julien, I'm starting to get a sense these days of some change of heart."

—Interview with Jacques Rivette in 2007[42]

It was nominated for the 2003 Prix Louis-Delluc.[33] Senses of Cinema suggested that it is Rivette's most important work since his 1974 film Celine and Julie Go Boating and saw it as "a film about filmmaking",[9] including it in their favourite films of 2004.[6] DVD Verdict concluded that "it is not only intelligent, but willing to assume the same of its audience".[17] Glenn Kenny rated it as his favourite film of the decade,[21] and film curator Miriam Bale writing in Slant Magazine included it in her ten most enduring films of the decade.[43] Film Comment was equally taken with the film, stating that "what's most remarkable about the film is how moving it is finally, how much is at stake after all—nothing Rivette has done before prepares you for the emotional undertow that exerts itself in The Story of Marie and Julien's final scenes."[22] LA Weekly described the film as "elegant and unsettling";[24] The Age called it "quietly mysterious and haunting"[19] and "heartrending".[44]

Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian was disappointed, arguing that "All the story's power is allowed to leak away by the deliberative heaviness with which Rivette pads through his 150-minute narrative, with its exasperating lack of dramatic emphasis."[45] Philip French noted similarities to Hitchcock's Vertigo and Jean Cocteau's Orphée, but called it "surprisingly flat and unmagical".[46] The New York Times also found it "dry and overdetermined,"[4] and Time Out complained that it "never supplies the frissons expected of a ghost story or the emotional draw of a good love story."[14] Film 4 compared it to The Sixth Sense and The Others, but said that "its glacially slow pace will frustrate all but the most patient".[8] (Rivette said when promoting the film that "I like The Sixth Sense because the final twist doesn't challenge everything that went before it. You can see it again, which I did, and it's a second film that's just as logical as the first one. But the end of The Others made the rest of it meaningless."[16]) "An intellectual exercise in metaphysical romance - Ghost for art-house audiences" was Empire's wry take.[20] The Digital Fix argued that Rivette's direction resulted in a product that "if never exactly dull and certainly the work of a master, is ultimately an empty film that has nothing to offer but its own cleverness".[35] Keith Uhlich of Slant Magazine found it was "a lesser Rivette offering — a watchable, ultimately unfulfilling ghost story".[39]

Distribution

The film was ignored by both Cannes and Venice,[2] then premièred at the Toronto International Film Festival on 10 September 2003.[24] It was shown in competition at the San Sebastian International Film Festival later that month,[47] as well as at the 2004 Melbourne International Film Festival[44][48] and the 2004 International Film Festival Rotterdam,[49] among others.[50] The film opened in France and Belgium on 12 November 2003; that night 239 people watched the film in Paris.[51] The cinema release was on 26 August 2004 in Germany,[52] and on 8 October 2004 in the UK,[14][53] but there was no US cinema release.[23]

The DVD was released on a two-disc set by Arte Video in France on 18 May 2004,[54] and features the theatrical trailer, actor filmographies, a 40-minute interview with Rivette, covering the film's origin, mythology, narrative viewpoints and relations to his other films, and a 15-minute interview with Béart, covering working under Rivette's direction and how the experience of acting in the film compared to her earlier role in La Belle Noiseuse.[3][13][17] The US and UK distributions, respectively released on 12 July 2005 by Koch Lorber Films and 28 February 2005 by Artificial Eye, come with optional English subtitles and the special features on a single disc.[23][54] The Arte Video release additionally features commentary by Lubtchansky over a cut-down (41:45 minute) version of the film, and an analysis of the film by Hélène Frappat (21:28 minutes).[35] The film was also released with Un Coeur en Hiver and Nathalie... in "The Emmanuel Beart Collection" by Koch Lorber in 2007.[55][56]

References

- "Histoire de Marie et Julien". Film and Television Database. BFI. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Fainaru, Dan (22 October 2003). "The Story Of Marie And Julien". Screendaily. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- "Histoire de Marie et Julien". Artificial Eye. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Kehr, Dave (19 July 2005). "Critic's Choice: New DVD's [sic]". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Raghavendra, MK. "The World as Narrative: Interpreting Jacques Rivette". Phalanx: A Quarterly Review for Continuing Debate. 2. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- "Senses of Cinema End of the Year 'Favorite Film Things' Compilation: 2004". Film Fest Journal. Acquarello. 2004. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Dawson, Tom (2 October 2004). "The Story Of Marie And Julien (Histoire De Marie Et Julien) (2004)". BBC Film. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- "Histoire De Marie Et Julien". Film 4. 2003. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Anderson, Michael J. (May 2004). "Histoire de Marie et Julien: Jacques Rivette's Material Ghost Story". Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Eschkötter, Daniel. "Was bleibt". Filmtext.com (in German). Archived from the original on 19 February 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Austin, Guy (February 2007). ""In Fear and Pain": Stardom and the Body in Two French Ghost Films". Scope. Institute of Film & Television Studies at the University of Nottingham (7). ISSN 1465-9166. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Rivette explains in an interview in the DVD special features that Marie is speaking Gaelic. The words are a geis that binds Julien to her. The geis is repeated in French to Julien after she speaks them alone in Gaelic.

- "Histoire de Marie et Julien (2003)". Movie Gazette. 26 March 2005. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- "Story of Marie and Julien". Time Out London. 6–13 October 2004. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Kite, B. (Fall 2007). "Jacques Rivette and the Other Place, Track 1b". Cinema Scope (32): 43–53. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- Johnston, Sheila (7 October 2004). "Jacques Rivette - summoning the ghosts of the past". The Times. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- Mancini, Dan (2 November 2005). "The Story Of Marie And Julien". DVD Verdict. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Rossinière, Marie (23 November 2003). "Un grand film-fantôme de Jacques Rivette". Largeur (in French). Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- Hawker, Philippa (1 June 2006). "Story of Marie and Julien". The Age. Australia. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Morrison, Alan. "Histoire De Marie Et Julien". Empire. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Kenny, Glenn (18 December 2009). "Films of the decade: "The Story of Marie and Julien"". [Salon. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Smith, Gavin (1 November 2003). "Unfamiliar haunts". Film Comment.

- Atkinson, Michael (26 July 2005). "A Beautiful Troublemaker: Rivette's Mystery Without Facts". Village Voice. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- Foundas, Scott (25 September 2003). "Master, Old and New". LA Weekly. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Johnston, Sheila (15 July 2004). "Emmanuelle Béart". The Times. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "Jacques Rivette: A Differential Cinema". Harvard Film Archive. Winter 2006. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- "Rivette: Texts & Interviews". British Film Institute. 1977. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- "Histoire de Marie et Julien press conference". Reeling Reviews. September 2003. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- Azoury, Philippe (12 November 2003). ""Marie et Julien", bel émoi dormant". Liberation (in French). Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "Le Pont du Nord (1981)". Cinema Talk. 9 September 2008. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- Jameson, A D (8 May 2010). "In Memory of William Lubtchansky". Big Other. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- Azoury, Philippe (20 March 2002). "Ces Rivette qu'on aurait dû voir". Libération (in French). Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Sabrina (12 November 2003). "Histoire de Marie et Julien". Ecran Noir (in French). Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- Frappat, Hélène (November 2003). "The Revenant". Cahiers du cinéma (in French) (584).

- Megahey, Noel (7 March 2005). "Histoire de Marie et Julien (2003) Region 2 DVD Video Review". The Digital Fix. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "Co-production support – Year 2002". Eurimages. Council of Europe. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- Hazette, Valérie (October 2003). "Hurlevent: Jacques Rivette's Adaptation of Wuthering Heights". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- Interview with Jacques Rivette, DVD special feature.

- Uhlich, Keith (21 December 2006). "Jacques Rivette at MOMI: Weeks 7 & 8". The House Next Door. Slant Magazine. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Bialas, Dunja. "Die Geschichte von Marie und Julien". Artechock (in German). Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- Interview with Emmanuelle Béart, DVD special features.

- Lalanne, Jean-Marc; Morain, Jean-Baptiste (30 March 2007). "Jacques Rivette Interview - L'art secret". Les Inrockuptibles. Translated by Keller, Craig; Coppola, Joseph. Retrieved 15 May 2010. Original French: "Q: Est-ce que la mauvaise réception de L'Histoire de Marie et Julien vous a blessé? A: On souhaiterait toujours qu'il y ait davantage de réponses. Mais souvent elles viennent cinq ans, dix ans plus tard. Il se trouve que, pour Marie et Julien, je commence à avoir des retours aujourd'hui." Translation at

- Bale, Miriam (30 December 2009). "Shifted Images". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- Martin, Adrian (9 August 2004). "Encounters in the dark". The Age. Australia. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Bradshaw, Peter (8 October 2004). "Histoire de Marie et Julien". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- French, Philip (10 October 2004). "Histoire de Marie et Julien". The Observer. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- "Young Helmers In Focus At San Sebastian". The Hollywood Reporter. 26 August 2003. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "Story of Marie and Julien, The". Melbourne International Film Festival. 2004. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- Chowdhury, Sabbir (8 February 2004). "IFFR: anatomy of a film festival". Daily Star (Bangladesh). India. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- "Histoire de Marie et Julien (2003)". Unifrance. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- "1ères séances : Paris se souvient ..." Allocine (in French). 12 November 2003. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Knörer, Ekkehard (26 August 2004). "Die schöne Leiche". Taz (in German). Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- "This week". The Film Programme. BBC Radio 4. 9 October 2004. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "Histoire de Marie et Julien". DVD Beaver. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Atanasov, Svet (17 July 2007). "The Emmanuelle Beart Collection". DVD Talk. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- "The Emmanuelle Beart Collection". Koch Lorber Films. 17 July 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

Further reading

- Rivette, Jacques; Frappat, Hélène (2002). Trois films fantômes de Jacques Rivette: précédé d'un mode d'emploi (in French). Cahiers du cinéma. ISBN 2-86642-322-4.

- Chakali, Saad (December 2003). "Analyse: Histoire de Marie et Julien". Cadrage (in French).

- Rivette, Jacques; De Pascale, Goffredo (2003). Jacques Rivette (in Italian). Il Castoro. ISBN 88-8033-256-2.

External links

- The Story of Marie and Julien at IMDb

- The Story of Marie and Julien at Rotten Tomatoes

- Trailer for Histoire de Marie et Julien on Cinemovies (in French, Flash video)