The Tale Of Two Bad Mice

The Tale of Two Bad Mice is a children's book written and illustrated by Beatrix Potter, and published by Frederick Warne & Co. in September 1904. Potter took inspiration for the tale from two mice caught in a cage-trap in her cousin's home and a doll's house being constructed by her editor and publisher Norman Warne as a Christmas gift for his niece Winifred. While the tale was being developed, Potter and Warne fell in love and became engaged, much to the annoyance of Potter's parents, who were grooming their daughter to be a permanent resident and housekeeper in their London home.

First edition cover | |

| Author | Beatrix Potter |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Beatrix Potter |

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's literature |

| Publisher | Frederick Warne & Co. |

Publication date | September 1904 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| Preceded by | The Tale of Benjamin Bunny |

| Followed by | The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle |

The tale is about two mice who vandalize a doll's house. After finding the food on the dining room table made of plaster, they smash the dishes, throw the doll clothing out the window, tear the bolster, and carry off a number of articles to their mouse-hole. When the little girl who owns the doll's house discovers the destruction, she positions a policeman doll outside the front door to ward off any future depredation. The two mice atone for their crime spree by putting a crooked sixpence in the doll's stocking on Christmas Eve and sweeping the house every morning with a dust-pan and broom.

The tale's themes of rebellion, insurrection, and individualism reflect not only Potter's desire to free herself of her domineering parents and build a home of her own, but her fears about independence and her frustrations with Victorian domesticity.

The book was critically well received and brought Potter her first fan letter from America. The tale was adapted to a segment in the 1971 Royal Ballet film The Tales of Beatrix Potter and to an animated episode in the BBC series The World of Peter Rabbit and Friends. Merchandise inspired by the tale includes Beswick Pottery porcelain figurines and Schmid music boxes.

Development and publication

The Tale of Two Bad Mice had its genesis in June 1903 when Potter rescued two mice from a cage-trap in her cousin Caroline Hutton's kitchen at Harescombe Grange, Gloucestershire, and named them Tom Thumb and Hunca Munca after characters in Henry Fielding's play, Tom Thumb.[1][2] Tom Thumb was never mentioned in Potter's letters after his rescue from the trap (he may have escaped) but Hunca Munca became a pet and a model; she developed an affectionate personality and displayed good housekeeping skills.[2]

Between November 26, 1903 and December 2, 1903, Potter took a week's holiday in Hastings, and, though there is no evidence that she did so, she may have taken one or both mice with her. She composed three tales in a stiff-covered exercise book during a week of relentless rain: Something very very NICE (which, after much revision, eventually became The Pie and the Patty-Pan in 1905), The Tale of Tuppenny (which eventually became Chapter 1 in The Fairy Caravan in 1929), and The Tale of Hunca Munca or The Tale of Two Bad Mice.[3][4][5] Potter hoped that one of the three tales would be chosen for publication in 1904 as a companion piece to Benjamin Bunny, which was then a work in progress. "I have tried to make a cat story that would use some of the sketches of a cottage I drew the summer before last," she wrote to her editor Norman Warne on December 2, "There are two others in the copy book ... the dolls would make a funny one, but it is rather soon to have another mouse book?", referring to her recently published The Tailor of Gloucester.[5]

Warne received and considered the three tales. Potter wrote to him that the cat tale would be the easiest to put together from her existing sketches but preferred to develop the mouse tale. She alerted Warne that she was spending a week with a cousin at Melford Hall and would run the three tales past the children in the house. Warne favoured the mouse tale – perhaps because he was constructing a doll's house in his basement workshop for his niece Winifred Warne – but for the moment, he delayed making a decision and turned his attention to the size of the second book for 1904 because Potter was complaining about being "cramped" with small drawings and was tempted to put more in them than they could hold. Warne suggested a 215 mm x 150 mm format similar to L. Leslie Brooke's recently published Johnny Crow's Garden, but, in the end, Potter opted for the mouse tale in a small format, instinctively aware the format would be more appropriate for a mouse tale and indicating it would be difficult to spread the mice over a large page. Before a final decision was made, Warne fashioned a large format dummy book called The Tale of the Doll's House and Hunca Munca with pictures and text snipped from The Tailor to give Potter a general impression of how a large format product would appear, but Potter remained adamant and the small format and the title The Tale of Two Bad Mice were finally chosen.[6]

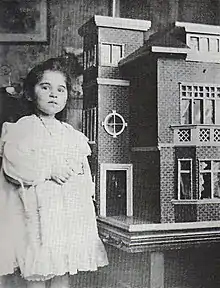

Just before New Year's 1904, Warne sent Potter a glass-fronted mouse house with a ladder to an upstairs nesting loft built to her specifications so she could easily observe and draw the mice.[7] The doll's house Potter used as a model was one Warne had built in his basement workshop as a Christmas gift for his four-year-old niece Winifred Warne. Potter had seen the house under construction and wanted to sketch it, but the house had been moved just before Christmas to Fruing Warne's home south of London in Surbiton. Norman Warne invited Potter to have lunch in Surbiton and sketch the doll's house, but Mrs. Potter intervened. She had taken alarm at the growing intimacy between her daughter and Warne; as a consequence, she made the family carriage unavailable to her daughter, and refused to chaperone her to the home of those she considered her social inferiors. Potter declined the invitation and berated herself for not standing up to her mother. She became concerned that the whole project could be compromised.[7]

On February 12, 1904 Potter wrote to Warne and apologized for not accepting his invitation to Surbiton. She wrote that progress was being made on the mouse tale, and once found Hunca Munca carrying a beribboned doll up the ladder into her nest. She noted that the mouse despised the plaster food. She assured him she could complete the book from photographs. On February 18, 1904 Warne bought the Lucinda and Jane dolls at a shop in Seven Dials and sent them to Potter. Potter wrote:

Thank you so much for the queer little dollies; they are exactly what I wanted ... I will provide a print dress and a smile for Jane; her little stumpy feet are so funny. I think I shall make a dear little book of it. I shall be glad to get done woth [sic] the rabbits ... I shall be very glad of the little stove and the ham; the work is always a very great pleasure anyhow.[8]

The policeman doll was borrowed from Winifred Warne. She was reluctant to part with it but the doll was safely returned. Many years later she remembered Potter arriving at the house to borrow the doll:

She was very unfashionably dressed; and wore a coat and skirt and hat, and carried a man's umbrella. She came up to the nursery dressed in her outdoor clothes and asked if she might borrow the policeman doll; Nanny hunted for the doll and eventually found it. It was at least a foot high, and quite out of proportion to the doll's house."[8]

On February 25 Warne sent plaster food and miniature furniture from Hamleys, a London toy shop.[8][9] On April 20 the photographs of the doll's house were delivered, and at the end of May Potter wrote to Warne that eighteen of the mouse drawings were complete, and the remainder were in progress. By the middle of June proofs of the text had arrived, and after a few corrections, Potter wrote on June 28 that she was satisfied with the alterations. Proofs of the illustrations were delivered, and Potter was satisfied with them.[10] In September 1904 20,000 copies of the book were published in two different bindings – one in paper boards and the other in a deluxe binding designed by Potter. The book was dedicated to Winifred Warne, "the girl who had the doll's house".[11][12]

In the summer of 1905 Hunca Munca died after falling from a chandelier while playing with Potter. She wrote to Warne on July 21: "I have made a little doll of poor Hunca Munca. I cannot forgive myself for letting her tumble. I do so miss her. She fell off the chandelier; she managed to stagger up the staircase into your little house, but she died in my hand about ten minutes after. I think if I had broken my own neck it would have saved a deal of trouble."[13]

Between 1907 and 1912 Potter wrote miniature letters to children as from characters in her books. The letters reveal more about their characters and their doings. Though many were probably lost or destroyed, a few are extant from the characters in Two Bad Mice. In one, Jane Dollcook has broken the soup tureen and both her legs; in another, Tom Thumb writes to Lucinda asking her to spare a feather bed which she regrets she cannot send because the one he stole was never replaced. Tom Thumb and Hunca Munca have nine children and the parents need another kettle for boiling water. Hunca Munca is apparently not a very conscientious housekeeper because Lucinda complains of dust on the mantlepiece.[14]

In 1971, Hunca Munca and Tom Thumb appeared in a segment of the Royal Ballet film The Tales of Beatrix Potter, and, in 1995, the tale was adapted to animation and telecast on the BBC anthology series The World of Peter Rabbit and Friends.

Plot

Two Bad Mice reflects Potter's deepening happiness in her professional and personal relationship with Norman Warne and her delight in trouncing the rigors and strictures of middle class domesticity. For all the destruction the mice wreak, it is miniaturized and thus more amusing than serious. Potter enjoyed developing a tale that gave her the vicarious thrill of the sort of improper behaviour she would never have entertained in real life.[15]

The tale begins with "once upon a time" and a description of a "very beautiful doll's-house" belonging to a doll called Lucinda and her cook-doll Jane. Jane never cooks because the doll's-house food is made of plaster and was "bought ready-made, in a box full of shavings". Though the food will not come off the plates, it is "extremely beautiful".

One morning the dolls leave the nursery for a drive in their perambulator. No one is in the nursery when Tom Thumb and Hunca Munca, two mice living under the skirting board, peep out and cross the hearthrug to the doll's-house. They open the door, enter, and "squeak for joy" when they discover the dining table set for dinner. It is "all so convenient!" Tom Thumb discovers the food is plaster and loses his temper. The two smash every dish on the table – "bang, bang, smash, smash!" – and even try to burn one in the "red-hot crinkly paper fire" in the kitchen fireplace.

Tom Thumb scurries up the sootless chimney while Hunca Munca empties the kitchen canisters of their red and blue beads. Tom Thumb takes the dolls' dresses from the chest of drawers and tosses them out the window while Hunca Munca pulls the feathers from the dolls' bolster. In the midst of her mischief, Hunca Munca remembers she needs a bolster and the two take the dolls' bolster to their mouse-hole. They carry off several small odds and ends from the doll's-house including a cradle, however a bird cage and bookcase will not fit through the mouse-hole. The nursery door suddenly opens and the dolls return in their perambulator.

Lucinda and Jane are speechless when they behold the vandalism in their house. The little girl who owns the doll's-house gets a policeman doll and positions it at the front door, but her nurse is more practical and sets a mouse-trap. The narrator believes the mice are not "so very naughty after all": Tom Thumb pays for his crimes with a crooked sixpence placed in the doll's stocking on Christmas Eve and Hunca Munca atones for her hand in the destruction by sweeping the doll's-house every morning with her dust-pan and broom.

Illustrations

Ruth K. MacDonald, author of Beatrix Potter (1986), believes the success of The Tale of Two Mice lies in the plentiful and meticulous miniature details of the doll's house in the illustrations. Potter persistently and consistently pursued a mouse-eye perspective and accuracy in the drawings. She could not have clearly seen the staircase down which the mice drag the bolster because it was impossible to take a photograph at that location, yet she placed herself imaginatively on the staircase and drew the mice in anatomically believable postures and in scale with the features of the doll's house. She took so much pleasure in the many miniature furnishings of the doll's house that Warne cautioned her about overwhelming the spectator with too many in the illustrations. The small format of the book miniaturizes the illustrations further, and their outline borders make the details appear even smaller both by the illusion of diminution the borders create and by limiting the picture to less than the full page.[16]

Themes

M. Daphne Kutzer, Professor of English at the State University of New York at Plattsburgh thinks The Tale of Two Bad Mice is a transitional work in Potter's career and reflects her concerns and questions about the meaning of domesticity, work, and social hierarchies. Changes in Potter's life were reflected in her art, Kutzer notes. In August 1905, Potter not only lost her editor and fiancé Norman Warne but purchased Hill Top, a working farm in the Lake District that became her home away from London and her artistic retreat. Two Bad Mice may be viewed as an allegory in which Potter expresses not only her desire for her own home but her fears about and frustrations with domestic life. While earlier works reflect Potter's interest in broad political and social issues, Two Bad Mice demonstrates her interests shifting to local politics and the lives of countrypeople.[17]

The book reflects Potter's conflicted feelings about rebellion and domesticity – about her desire to flee her parents' home via a "rebellious" engagement to Norman Warne and her purchase of a domestic space that would be built with her fiancé. Kutzer points out that the tale has three settings: that of the humans, that of the doll's house, and that of the mice, and that the themes of the book include "domesticity and the role of domiciles within domesticity" and tensions about the pleasures and dangers of domesticity and of rebellion and insurrection.[18]

The human and doll's house worlds reflect Potter's upper-middle-class background and origins: the proper little girl who owns the doll's house has a governess and the doll's house has servants' quarters and is furnished with gilt clocks, vases of flowers, and other accoutrements that bespeak the middle class. Kutzer points out that Potter is not on the side of the respectable middle class in this tale however: she is on the side of subversion, insurrection and individualism. The book is a miniature declaration of Potter's increasing independence from her family and her desire to have a home of her own, yet at the same time reflects her ambivalence about leaving home and her parents.[19]

Kutzer observes the tale is marked with a "faint echo" of the larger class issues of the times, specifically labour unrest. The mice, she suggests, can be viewed as representatives of the various rebellions of the working classes against working conditions of England and the growing local political and industrial conflicts revolving around issues such as the recognition of new unionism, working conditions, minimum wages, an 8-hour day, and the closed shop. She disapproved of the use of violence to attain reform but not of reform itself.[20]

Kutzer further believes that however much Potter wished to provide an example of moral behaviour for the reader in the last pages of the tale (the mice "paying" for their misdeeds), her sense of fairness and the subtext of British class unrest actually account for the tale's ending. Social authority (the policeman doll) and domestic authority (the governess) are both ineffective against the desires of the mice: one illustration depicts the animals simply evading the policeman doll to prowl outside the house and another illustration depicts the mice instructing their children about the dangers of the governess's mousetrap. Their repentance is merely show: Tom Thumb pays for his destruction with a useless crooked sixpence found under the rug and Hunca Munca cleans a house that is tidy to begin with. Their respectful show of repentance covers up their continuing rebellion against middle class authority. Although Potter approves of the domestic and social rebellion of the mice and their desire for a comfortable house of their own, she disapproves of the emptiness and sterility of the dolls' lives in the doll's house yet understands the attractions of a comfortable life made possible in part by the labour of servants.[21]

Reception

A reviewer in Bookman thought Two Bad Mice a pleasant change from Potter's rabbit books (Peter Rabbit and Benjamin Bunny) and believed neither Tom Thumb or Hunca Munca were completely bad, noting they both looked innocent and lovable in Potter's twenty-seven watercolour drawings. The reviewer approved Potter's "Chelsea-china like books" that were Warne's "annual marvels ... to an adoring nursery world".[3]

Potter received her first fan letter from an American youngster in the wake of Two Bad Mice. Hugh Bridgeman wrote to say he enjoyed the book, and Potter in return wrote him, "I like writing stories. I should like to write lots and lots! I have ever so many inside my head but the pictures take such a dreadful long time to draw! I get quite tired of the pictures before the book is finished."[22]

Merchandise

Potter confidently asserted her tales would one day be nursery classics, and part of the process in making them so was marketing strategy.[23] She was the first to exploit the commercial possibilities of her characters and tales with a Peter Rabbit doll, a board game, and a nursery wallpaper between 1903 and 1905.[24] Similar "side-shows" (as she termed the ancillary merchandise) were conducted over the following two decades.[25]

In 1947 Frederick Warne & Co. gave Beswick Pottery of Longton, Staffordshire rights and licences to produce the Potter characters in porcelain. Seven figurines inspired by Two Bad Mice were issued between 1951 and 2000: Hunca Munca with the Cradle; Hunca Munca Sweeping; Tom Thumb; Christmas Stocking; Hunca Munca Spills the Beads; Hunca Munca cast in a large-sized, limited edition; and another Hunca Munca.[26]

In 1977 Schmid & Co. of Toronto and Randolph, Massachusetts was granted licensing rights to Beatrix Potter, and released two music boxes in 1981: one topped with a porcelain figure of Hunca Munca, and the other with Hunca Munca and her babies. Beginning in 1983, Schmid released a series of small, flat hanging Christmas ornaments depicting various Potter characters including several Hunca Muncas. In 1991, three music boxes were released: Hunca Munca and Tom Thumb in the dolls' bed (playing "Beautiful Dreamer"); Tom Thumb instructing his children about the dangers of mouse traps ("You've Got a Friend"); Hunca Munca spilling the beads from the pantry canister ("Everything is Beautiful"); and the two mice trying to cut the plaster ham ("Close to You"). Another music box released the same year played "Home! Sweet Home!" and depicted the exterior of the doll house, and, when reversed, the interior of the house with the bedroom upstairs and the dining room downstairs. Three separate mouse figurines could be placed here and there in the house.[27]

Translations and reprints

Potter's 23 little books have been translated into nearly thirty languages including Greek and Russian. The English language editions still bear the Frederick Warne imprint though the company was bought by Penguin Books in 1983. The task of remaking the printing plates for all 23 volumes of the Peter Rabbit collection from the very beginning with new photographs of the original drawings and new designs in the style of the original bindings was undertaken by Penguin in 1985, a project completed in two years and released in 1987 as The Original and Authorized Edition.[28]

The Tale of Peter Rabbit was the first of Potter's books to be translated when the Dutch edition of Peter Rabbit (Het Verhaal van Pieter Langoor) was published in 1912 under licence by Nijgh & Ditmar's Uitgevers Maatschappij, Rotterdam. The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck (Het Verhall van Kwakkel Waggel-Eend) followed the same year. Peter Rabbit and five other tales were published in Braille by The Royal Institute for the Blind in 1921. Twee Stoute Muisjes (Two Bad Mice) was first published in Dutch in 1946 and republished under licence as Het Verhaal van Twee Stoute Muizen (The Tale of Two Bad Mice) by Uitgeverij Ploegsma, Amsterdam in 1969. Two Bad Mice was first published in German as Die Geschichte von den zwei bösen Mäuschen in 1939, and was under licence to be published by Fukuinkan-Shoten, Tokyo in Japanese in 1971.[29]

Adaptations

The Tale of Two Bad Mice is included as a segment in the 1971 Royal Ballet film Tales of Beatrix Potter.

Between 1992 and 1996, a number of Beatrix Potter's tales were turned into an animated television series and broadcast by the BBC, titled The World of Peter Rabbit and Friends. One of the episodes is an adaptation of both The Tale of Two Bad Mice and The Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse. In the episode, Hunca Munca is voiced by Felicity Kendal and Tom Thumb is voiced by Rik Mayall. It first aired on the BBC on June 29, 1994.

References

- Taylor, p. 119

- Lane 2001, pp. 77-8

- Lear 2007, p. 185

- Taylor, p. 118

- Linder 1971, p. 149

- Linder 1971, pp. 149–50

- Lear 2007, p. 176

- Linder 1971, p. 151

- Lear 2007, p. 177

- Linder 1971, pp. 152-3

- Lear 2007, pp. 178,181

- Linder 1971, p. 153

- Linder 1971, p. 154

- Linder 1971, pp. 72,76–77

- Lear 2007, pp. 184-5

- MacDonald 1986, pp. 73–4

- Kutzer 2003, p. 65

- Kutzer 2003, p. 66

- Kutzer 2003, p. 67

- Kutzer 2003, p. 75

- Kutzer 2003, pp. 75-6

- Lear 2007, p. 192

- MacDonald 1986, p. 128

- Lear 2007, pp. 172-5

- Taylor 1987, p. 106

- DuBay 2006, pp. 30,34

- DuBay 2006, pp. 106,108,116-7

- Taylor 1996, p. 216

- Linder 1971, pp. 433-37

Works cited

- DuBay, Debby & Kara Sewall (2006). Beatrix Potter Collectibles: The Peter Rabbit Story Characters. Schiffer Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7643-2358-X.

- Kutzer, M. Daphne (2003). Beatrix Potter: Writing in Code. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-94352-3.

- Lane, Margaret (2001) [1946]. The Tale of Beatrix Potter. London: Frederick Warne. ISBN 978-0-7232-4676-3.

- Lear, Linda (2007). Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-37796-0.

- Linder, Leslie (1971). The History of the Writings of Beatrix Potter including Unpublished Work. Frederick Warne. ISBN 0723213348.

- Taylor, Judy; et al. (1987). Beatrix Potter 1866–1943: The Artist and Her World. London: F. Warne & Co. and The National Trust. ISBN 0-7232-3561-9.

- Taylor, Judy (1996) [1986]. Beatrix Potter: Artist, Storyteller and Countrywoman. London: Frederick Warne. ISBN 0-7232-4175-9.

Bibliography

- Denyer, Susan (2009) [2001]. At Home with Beatrix Potter: The Creator of Peter Rabbit. London: Frances Lincoln Limited and The National Trust. ISBN 978-0-7112-3018-7.

- Hallinan, Camilla (2002). The Ultimate Peter Rabbit: A Visual Guide to the World of Beatrix Potter. London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7894-8538-9.

- Linder, Leslie & Enid Linder (1972) [1955]. The Art of Beatrix Potter. London: Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0-7232-1457-3.

External links

The full text of The Tale Of Two Bad Mice at Wikisource

The full text of The Tale Of Two Bad Mice at Wikisource Media related to The Tale of Two Bad Mice at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Tale of Two Bad Mice at Wikimedia Commons- The Tale of Two Bad Mice at Wired for Books

- The Tale of Two Bad Mice at Internet Archive

- The Tale of Two Bad Mice at ePub Bud