Thirsk and Malton line

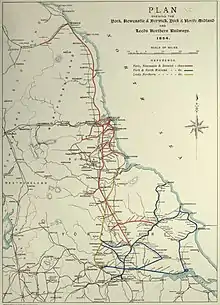

The Thirsk and Malton line was a railway line that ran from a triangular junction on what is now the East Coast Main Line and served eight villages between Thirsk and Malton in North Yorkshire, England. The line was built after a protracted process due to inefficiencies and financial problems suffered by the then York and North Midland Railway.

| Thirsk and Malton line | |

|---|---|

Gilling station looking east. The platforms were behind the Station House and the goods warehouse is on the right above the gate. | |

| Overview | |

| Status | Closed |

| Locale | North Yorkshire |

| Termini | Sunbeck Junction and the East Coast Main Line Scarborough Road Junction Malton |

| Stations | 8 |

| Service | |

| Type | Heavy Rail |

| Operator(s) | North Eastern Railway London North Eastern Railway British Rail |

| History | |

| Opened | 19 May 1853[1] |

| Closed | (Completely) October 1964[2] |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 22 miles 52 chains (36.5 km) |

| Number of tracks | 1 |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

| Operating speed | 20 miles per hour (32 km/h) Pilmoor – Gilling 30 miles per hour (48 km/h) Gilling – Malton |

| Thirsk & Malton line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The line was opened in 1853 and connected with the Malton and Driffield Junction Railway at Scarborough Road Junction just east of Malton. The entire route was initially envisaged as a through route between Hull and Glasgow, but it mostly ended up serving the local communities on the line. Express workings regularly used it between Scarborough and Newcastle, but they were reduced to a slower speed than usual because of the lower speeds on the rural lines. The line closed to passengers between Gilling and Malton in December 1930. The section from the East Coast Main Line (ECML) to Gilling was retained after closure as the branch from Gilling to Pickering did not close to passengers until 1953 with complete closure coming in 1964.

History 1853–1930

Several companies were vying to build railways across Ryedale, but in 1846, the Newcastle and Darlington Junction Railway received assent from Parliament for the construction of a line towards Malton from what was the Great North of England Railway's route between York and Darlington.[3] Several amalgamations later and construction was started in October 1851[4] with the Thirsk and Malton (T & M) Line opening in 1853 under the York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway.[5] In 1854, the Y, N & B became a constituent part of the North Eastern Railway and the Thirsk and Malton railway became an asset of the NER.[6]

The branch was built with north and south facing junctions on the York, Newcastle and Berwick line (what today is known as the East Coast Main Line). Both Sessay Wood Junction (north) and Bishophouse Junction (south) had double track formations that verged eastwards and narrowed into a single line at Sunbeck Junction. Bishophouse Junction to Sunbeck Junction was not opened until 9 October 1871, when the Gilling and Pickering (G & P) route opened up to traffic.[7]

The line then proceeded in a north easterly direction towards Husthwaite Gate and Coxwold, before going due east to Ampleforth and Gilling. At Gilling there was a spur to the north for the Gilling and Pickering Line, whereas the Thirsk and Malton Line headed south eastwards through Hovingham, Slingsby, Barton-le-Street and Amotherby before crossing the York to Scarborough line on an overbridge and arriving at Scarborough Road Junction, Malton.[8] The line was 22 miles 52 chains (36.5 km)[9] in length with a further section of 68 chains (1.4 km) from Scarborough Road Junction to Malton Station.[10]

The line was single throughout with passing loops at Coxwold and Gilling. The place where the G & P ran north from the Thirsk and Malton line was listed as Parliamentary Junction,[note 1][11] but in effect it was two single lines eastwards from Gilling Station which diverged without a junction. This was an economy measure meaning that the NER didn't need to install any points or employ staff to operate them. The two lines ran parallel to each other for 2 miles (3.2 km) out of Gilling Station.[12] When the G & P was constructed, it was not necessary to obtain extra land for the formation east of Gilling to Parliamentary Junction as the original T & M proposal involved buying enough land for double track. In the end, only a single line was constructed and all bridges were built for single lines only leaving a large slice of unused land inside the railway fencing.[11]

Trains for Malton needed to stop at Scarborough Road Junction and then reverse into Malton station using the Malton and Driffield lines. Trains for Gilling, Pilmoor and Thirsk had to do the same manoeuvre in reverse. Save for the odd excursion, summer only Filey Holiday Camp trains and stone traffic, no trains went through directly from Thirsk to Driffield.[13] Stations on the section between Gilling and Scarborough Road Junction saw their last regular passenger trains on 30 December 1930 with official closure coming on 1 January 1931.[14] By 1914, the services on this stretch of the line had been downgraded to run between Gilling and Malton with a connection to the Pickering to York services at Gilling Station.[15] Four services a day operated on this section.[16] The stations remained open for goods and it was possible to travel as a passenger from these stations on Summer Saturday's only until complete closure.[5]

The other four stations between Sunbeck Junction and Gilling were kept open for services using the Gilling and Pickering line. The passenger services on this line amounted to two daily workings in each direction from York. By 1944, the LNER timetable shows just one through working to York and a daily working to Alne on the East Coast Main Line with connections on to York from there.[17]

History 1930–1964

Express trains did use the branch between 1930 and 1962 with services between Glasgow and Scarborough. These summer only services would use the G & P line east of Gilling and they were reduced to a 'trundle' when using the route (as the linespeeds were between 20 miles per hour (32 km/h) and 30 miles per hour (48 km/h)).[5] The route was also used by Scarborough to Middlesbrough services when the coastal route through Robin Hood's bay was at capacity.[12]

On 1 January 1948, the Ryedale lines came under the control of British Rail. Passenger traffic carried on for a further 5 years on the western edge of the line between Gilling and Hustwaite Gate (the York to Pickering services that used the G & P line). All stations on the line were closed to passengers by 26 February 1953,[18] however many excursions, diversions and expresses still used the line.[16] Traffic exchanging lines at Malton was hauled to and from Scarborough Road Junction with a pilot engine attached at the rear of the train. This allowed the engine of the train to be facing in the right direction when it came to leave Malton or Scarborough Road Junction. A turntable was available at Malton, but a pilot engine helped with the gradient on the Malton to Driffield Junction line.[5][19]

A derailment at Pilmoor on 19 March 1963 damaged the Junction at Sessay Wood. By this point only the express and excursion passenger trains were working over this section and so it was decided not to repair it. Goods traffic was limited to a daily pick up-goods and the expresses could be re-routed via Malton and York.[20]

Closure of the system to all traffic came on 7 August 1964. The section from Amotherby to Malton via reversal at Scarborough Road Junction was retained until October 1964 to fulfill a contract with BATA (Brandsby Agricultural Trading Association) at Amotherby Mill. After this, all the lines were removed.[21]

Stations

Although it was initially proposed as a through Hull to Glasgow route, the Thirsk and Malton Railway became a local branch line albeit connected to other lines at each end. Eight stations were constructed along the line and the table below lists the locations of each station (except Malton and the two stations either side of the triangular junction on the East Coast Main Line).

| Name | Coordinates | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Husthwaite Gate | 54°10′28.7″N 1°12′36.5″W | A small section of tramway existed here to aid in the removal of timber from Angram Wood 200 yards (180 m) north east of the station.[22] |

| Coxwold | 54°11′11.0″N 1°10′45.5″W | Coxwold had a passing loop which would be used for the morning trains to and from York to pass each other.[23] |

| Ampleforth | 54°10′58.3″N 1°07′13.5″W | Closed in 1950, three years before the other stations on the line.[15] |

| Gilling | 54°11′14.6″N 1°03′32.0″W | Only had one platform on opening. A second platform (and passing loop) was added when the G & P line opened in 1871. After this the station was sometimes known as Gilling Junction.[24] Was also known as 'Gilling for Ampleforth College', as it was more convenient to alight here for the college than at Ampleforth station itself.[25] |

| Hovingham Spa | 54°10′34.3″N 0°58′25.8″W | Originally just Hovingham. The word Spa was added to the station name in 1896.[9] |

| Slingsby | 54°10′11.4″N 0°55′52.4″W | Had a long siding into which trains could be shunted to allow others to pass.[26] |

| Barton-le-Street | 54°09′44.3″N 0°53′29.2″W | |

| Amotherby | 54°09′16.2″N 0°51′10.2″W | The mill adjacent to the station kept this section of the line open when the rest had been closed. British Rail had an agreement to serve the mill with the owners (BATA) which means the stretch of line to Amotherby did not close until October 1964, two months after everywhere else on the line.[27] |

Ampleforth College Tramway

Gilling was the station for passengers wishing to go to Ampleforth College and special trains would be run at the start and the end of term time. The college was equidistant between Ampleforth and Gilling Stations, but access was easier from Gilling. A 3 foot (0.91 m) gauge tramway was built in 1895 to connect Gilling with the College.[28] Open wagons were supplied to transport staff and pupils to the college from the station, but they were secondary to the main traffic which was coal for the gas boilers. The line was horse-drawn throughout its history (though at least one diesel/petrol locomotive was used) and was closed sometime after 1923 when the college changed over to electric lighting.[24]

Unused connection

One of the proposals in the building of the Pilmoor, Boroughbridge and Knaresborough Railway was a connection from that line directly onto the T & M Line east of Sunbeck Junction. Whilst the earthworks were built including a bridge over the ECML, the line was never installed. This was to have been a through route between Leeds and Scarborough.[29] The embankment of the unused railway on the western side of the ECML was the location of four signals that faced at 90 degrees to the running lines on the ECML. These were utilised for sight testing of drivers when on training runs out of York.[30][31]

Accidents and incidents

- On 30 December 1865, a train running tender first was incorrectly routed into a short siding at Ampleforth station. The train collided with a wagon on the siding being used by some bricklayers, one of whom was killed.[32] The points should have been locked out for the main line.[33]

- On 24 July 1911, 14 wagons of a goods train going east through Coxwold broke free on the gradient and rolled back down the line towards Husthwaite Gate. A member of staff at Husthwaite Gate managed to clamber aboard the errant wagons, despite them going faster than he could run, and succeeding in bringing the wagons to a stop by applying the brake in the guard's van.[22]

- On 16 April 1941, a train heading to York from Pickering fell into a bomb crater at 7:20 am between Gilling and Coxwold. The line was opened up again by 9:30 pm the same day.[16]

Post closure

The rails and bridges were removed in 1965[34] and most of the former railway buildings became private dwellings.[35]

Parts of the trackbed have been converted into pathways, especially at Slingsby and Fryton where the former line is part of the village heritage trail.[36]

Notes

- The name is taken from the Act of Parliament, meaning the G & P started there.

References

- Suggitt 2005, p. 97.

- Suggitt 2005, p. 99.

- Suggitt 2005, p. 96.

- "In detail". Yorkshire Wolds Railway. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Hoole 1974, p. 89.

- Chapman 2008, p. 5.

- Howat 2004, p. 112.

- "From City to Seaside". Rail Magazine. No. 491. EMAP Active. 7 July 2004. p. 45. ISSN 0953-4563.

- Howat 1988, p. 3.

- Chapman 2008, p. 104.

- Howat 1988, p. 16.

- Hoole 1983, p. 14.

- Howat 1988, p. 22.

- Burgess 2011, p. 14.

- Suggitt 2005, p. 98.

- Hoole 1983, p. 15.

- "Bradshaws Guide for Great Britain & Ireland no 1328: 1944". Internet Archive. Bradshaws. p. 979. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Howat 1988, p. i.

- Reed, Des (18 November 2010). "Tales of the railway awaken memories". Gazette & Herald. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Burgess 2011, p. 16.

- Howat 1988, p. 48.

- Howat 1988, p. 9.

- Howat 1988, p. 11.

- Catford, Nick. "Gilling". Disused Stations. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- Howat 1988, p. 13.

- Howat 1988, p. 18.

- Howat 1988, p. 20.

- Chapman 2008, p. 8.

- Burgess 2011, p. 20.

- Hoole 1977, p. 6.

- Hoole 1977, p. 55.

- Howat 1988, p. 12.

- "Accident Returns: Extract for the Accident at Ampleforth on 30th December 1865" (PDF). Railways Archive. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- Catford, Nick. "Ampleforth". Disused Stations. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Catford, Nick. "Coxwold". Disused Stations. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- "Slingsby country walk". Gazette & Herald. 7 October 2009. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

Bibliography

- Burgess, Neil (2011). The Lost Railways of Yorkshire's North Riding. Stenlake Publishing. ISBN 9781840335552.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chapman, Stephen (2008). York to Scarborough, Whitby & Ryedale. Bellcode Books. ISBN 9781871233 19 3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoole, Ken (1974). A regional history of the railways of Great Britain; Volume 4 – the North East. David & Charles. ISBN 0 7153 6439 1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoole, Ken (1977). Railways in Yorkshire 3; the North Riding. Dalesman Publishing. ISBN 0 85206 418 7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoole, Ken (1983). The Railways of the North Yorkshire Moors. Dalesman Publishing. ISBN 0 85206 731 3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howat, Patrick (1988). The Railways of Ryedale and the Vale of Mowbray. Hendon Publishing. ISBN 0 86067 111 9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howat, Patrick (2004). The Railways of Ryedale. Bairstow Publishing. ISBN 1-871944-29-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Suggitt, Gordon (2005). Lost Railways of North & East Yorkshire. Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-85306-918-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Young, Alan (2015). Lost Stations of Yorkshire; the North and East Ridings. Silverlink Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85794-453-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)