Thomas Peters (revolutionary)

Thomas Peters, born Thomas Potters (1738 – 25 June 1792),[1] was a veteran of the Black Pioneers, fighting for the British in the American Revolutionary War. A Black Loyalist, he was resettled in Nova Scotia, where he became a politician and one of the "Founding Fathers" of the nation of Sierra Leone in West Africa. Peters was among a group of influential Black Canadians who pressed the Crown to fulfill its commitment for land grants in Nova Scotia. Later they recruited African-American settlers in Nova Scotia for the colonisation of Sierra Leone in the late eighteenth century.

Thomas Peters | |

|---|---|

| Born | Thomas Potters 1738 |

| Died | 25 June 1792 (aged 53–54) |

| Cause of death | Malaria |

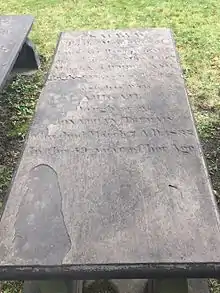

| Resting place | Freetown, Sierra Leone |

| Nationality | Nigerian, American, Canadian, Sierra Leonean |

| Citizenship | Canadian, Sierra Leonean |

| Occupation | Slave, soldier, politician, colonizer |

| Known for | Being a colonizer, of the mass recruitment of former, African American, Nova Scotia settlers, from British Canada, Northern America, to Sierra Leone Colony, West Africa |

| Spouse(s) | Sally Peters (m. 1776) |

| Children | John Peters (son) Clairy Peters (daughter) 5 other children |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Unit | Black Company of Pioneers |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

Enslaved in the Province of North Carolina, Peters emancipated himself and joined British forces during the American Revolutionary War. He served as a Black Loyalist in the Black Company of Pioneers in New York and was evacuated with British forces and many other former slaves at the end of the war. Thomas Peters has been called the "first African-American hero".[2] Like Elijah Johnson and Joseph Jenkins Roberts of Liberia, Peters is considered the African-American founding father of a nation, in this case, Sierra Leone.[3][4][5][6][7]

Early life

Thomas Peters was born in West Africa, to the Yoruba tribe, of the Egba clan.[5][8][9][10][11][12]

According to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography:

Legend has given Thomas Peters a noble birth in West Africa, whence he was supposedly kidnapped as a young man and brought as a slave to the American colonies. The earliest documentary evidence places him in 1776 as the 38-year-old slave of William Campbell in Wilmington, North Carolina. In that year, encouraged by the proclamation issued by Governor Lord Dunmore of Virginia in 1775 promising freedom to rebel-owned slaves who joined the loyalist forces, Peters fled Campbell’s plantation and enlisted in the Black Pioneers in New York. In 1779, in response to a new invitation to rebel-owned slaves to place themselves under British protection whether they wished to bear arms for the crown or not, a 26-year-old woman named Sally from Charleston, South Carolina, appeared in a British camp, and she too joined the Black Pioneers. In that service she met Peters, who by 1779 had been promoted sergeant, and they were married.[1]

Enslavement

In 1760, the twenty-two-year-old African, later called Thomas Peters, was captured by slave traders and sold as a slave to Colonial America on a French ship, the Henri Quatre. Upon arrival in North America, probably at New Orleans, he was sold to a French planter in French Louisiana. Peters tried to escape three times before being sold to an Englishman or Scotsman in one of the Southern Colonies. This was probably Campbell, an immigrant Scotsman, who had settled on the Cape Fear River in Wilmington, North Carolina.[10][11]

American Revolutionary War

In 1776, Peters escaped from his master's flour mill near Wilmington[13] at the start of the American Revolutionary War and migrated to New York, where he joined the Black Pioneers, a Black Loyalist unit made up of refugee African-American slaves. The British had previously promised freedom to slaves of rebels in exchange for supporting the war effort against the colonies that formed the new United States. Many former slaves joined the British in the years of the war after the United States had been established as a nation; under American law they were still considered slaves and the US demanded that the British return their "property."[14]

Migrating to New York, Peters rose to the rank of sergeant in the Black Pioneers regiment and he was twice wounded in battle. During this time, Thomas married Sally Peters, a refugee slave from South Carolina. They had a daughter called Clairy (born in 1771) and a son John (born in 1781). Sally and Peters may have once been slaves together in South Carolina and became reunited during the war.

Resettled in Province of Nova Scotia, British Canada

After the war Peters and some three thousand of other former African-American slaves were evacuated by the British, who had promised their freedom, and resettled in Nova Scotia, along with white Loyalists. The Crown allotted land to the pioneers and supplies to help with the first year. The Peters family resided here from 1783 to 1791. Initially after being evacuated from New York, the ship carrying Peters had been blown off course and the crew temporarily settled in Bermuda. Eventually Thomas Peters and his family settled in Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. Peters and his fellow Black Pioneer, Murphy Steele, petitioned the government for land together. Steele and Peters had developed a friendship during their service to the Black Pioneers.

Petition to settle in Sierra Leone Colony, West Africa

Peters became disheartened with what he saw as broken promises of land and aid by the British government. He and fellow Black Loyalists also suffered from discrimination by whites in Nova Scotia. He decided to travel to England to demand the land promised to him and others.[5] Peters gathered the signatures and marks of African-American settlers in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick before getting funds to travel to London and convince the Government to settle the blacks in Nova Scotia elsewhere.

In 1791, Peters went to London, where he helped convince the Royal government (with the help of Granville Sharp) to allow them to settle a new colony in West Africa. This was ultimately established as Freetown, Sierra Leone. Peters was well received during his trip to London, and he was introduced to some notable people by his former commander, General Henry Clinton, who was politically out of favour. It was decided in London that Peters and the Naval Officer John Clarkson, the brother of English abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, would assist in recruiting blacks to settle in Sierra Leone.[10][16]

Recruiting migrants for Sierra Leone

Peters returned to Nova Scotia triumphant in his quest. Together with leaders David George, Moses Wilkinson, Joseph Leonard, Cato Perkins, William Ash, John Ball, and Isiah Limerick promoted migration to Sierra Leone among the black pioneers in the communities of Birchtown, Halifax, Shelbourne, and Annapolis Royal. Peters and David Edmons (Edmonds) from Annapolis Royal petitioned John Clarkson for beef to celebrate their last Christmas in North America in 1791. David Edmonds eventually became a successful settler in Sierra Leone and a friend of Paul Cuffee, a Boston, Massachusetts businessman who also promoted resettlement of African Americans in Sierra Leone.

Sierra Leone

More than 1,100[17] of the 3,500 American blacks decided to migrate to West Africa. Most were from families with generations of birth in the British Thirteen Colonies; a few, like Peters, were returning to the Africa of their birth.

In 1792 they arrived at St. George Bay Harbor. According to legend, Thomas Peters led the Nova Scotians ashore singing an old Christian hymn (though most likely it was other more influential religious leaders). After John Clarkson was appointed as governor of the settlement, Peters became at odds with him; Peters called himself the "Speaker General" of the Annapolis Royal Nova Scotia settlers. Although he received support from influential figures amongst settlers such as Abraham Elliot Griffiths and Henry Beverhout,[18]:97 eventually the overwhelming majority of Nova Scotians affirmed John Clarkson as their leader. Peters became disheartened. He was among the many early settlers to die of disease in the early years of the colony.[5]

Peters was survived by his wife Sally and seven children. A number of Krios (descendants of the first African-American settlers) can claim descent from Peters. He is considered by many to be a founding father, a "George Washington"-type figure of Freetown, Sierra Leone.[1]

Legacy and honours

His descendants are members of the Creole ethnic group, known as the Krio people, who live predominantly in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Some of his descendants also live in Canada.[5]

In 1999 Peters was honoured by the Sierra Leone government by being included in a movie celebrating the country's national heroes. In 2001 supporters suggested renaming Percival Street (specifically Settler Town, Sierra Leone, where Peters's Nova Scotians settled) in Freetown in his honour, but this has not yet happened.[19]

Peters was portrayed by Leo Wringer in the BBC television series Rough Crossings (2007), based on a history of the British and American slaves during and after the Revolution, written by historian Simon Schama.

In 2011 a statue of Thomas Peters was erected in Freetown, commissioned by the Krio Descendants Union.[20]

See also

- Black Nova Scotians

- List of slaves

References

- James W. St G. Walker. "PETERS, THOMAS". Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4. University of Toronto. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Shabaka Reveals The "Black Moses", Thomas Peters, America's First African-American Hero. BlackNews.com.

- Rough Crossings – LASTAMPA.it

- "Peters, Thomas (1738–1792)". BlackPast. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Redmond Shannon (13 April 2016). "Saint John historian illuminates story of Thomas Peters, prominent black loyalist". New Brunswick: CBC News. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- Aphra Behn (7 March 2007). "Black History:Thomas Peters, Founder of Nations". Daily Kos. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- Bobby Gilmer Moss; Michael C. Scoggins (2005). African American loyalists in the southern campaign of the American Revolution. Scotia-Hibernia Press (University of Wisconsin - Madison). p. 240. ISBN 978-0-9762162-0-9.

- Sanneh (2001), p. 50.

- John Coleman De Graft-Johnson (1986). African Glory: The Story of Vanished Negro Civilizations. Black Classic Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-933121-03-4.

- Stewart J. Brown; Timothy Tackett (2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity (Enlightenment, Reawakening and Revolution 1660–1815). 7. Cambridge University Press. p. 421. ISBN 978-0-521-81605-2.

- William Dillon Piersen (1993). Black Legacy: America's Hidden Heritage. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-87023-859-8.

- Massala Reffell (2012). Echoes of Footsteps: Birth of a Negro Nation. Xlibris Corporation. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-4771-3026-1.

- Online Personal Albums by Ekahau – VirtualTourist.com

- "Black History: Thomas Peters, Founder of Nations (Pt 2)". Daily Kos.

- "Biography – HARTSHORNE, LAWRENCE – Volume VI (1821-1835) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography".

- Mary Louise Clifford (2006). From Slavery to Freetown: Black Loyalists After the American Revolution. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2557-0. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- Peter Fryer (1984). Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain. University of Alberta. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-86104-749-9. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Wilson, Ellen Gibson (1980). John Clarkson and the African Adventure. London: Macmillan Press.

- BBC NEWS | World | Africa | S Leone honours Africa slave campaigners

- A Tribute to Thomas Peters

Bibliography

- Simon Schama, Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and the American Revolution, BBC Books, ISBN 0-06-053916-X

- Sanneh, Lamin, Abolitionists Abroad: American Blacks and the Making of Modern West Africa, Harvard University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-674-00718-2

- The Blacks in Canada: A History. McGills University Press. February 1997. ISBN 978-0-7735-1632-8.

- James W. St. G. Walker (1992). The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783–1870. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802074027.

- Mary Louise Clifford (2006). From Slavery to Freetown: Black Loyalists After the American Revolution. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2557-0.

- Rucker Jr, Walter C.; Alexander, Leslie M. (2010). Encyclopedia of African American History. pp. 377–378. ISBN 978-1-85109-774-6.