Thoracic duct

In human anatomy, the thoracic duct is the larger of the two lymph ducts of the lymphatic system. It is also known as the left lymphatic duct, alimentary duct, chyliferous duct, and Van Hoorne's canal. The other duct is the right lymphatic duct. The thoracic duct carries chyle, a liquid containing both lymph and emulsified fats, rather than pure lymph. It also collects most of the lymph in the body other than from the right thorax, arm, head, and neck (which are drained by the right lymphatic duct).[1] The thoracic duct usually starts from the level of the twelfth thoracic vertebrae (T12) and extends to the root of the neck. It drains into the systemic (blood) circulation at the junction of the left subclavian and internal jugular veins, at the commencement of the brachiocephalic vein.[2]

| Thoracic duct | |

|---|---|

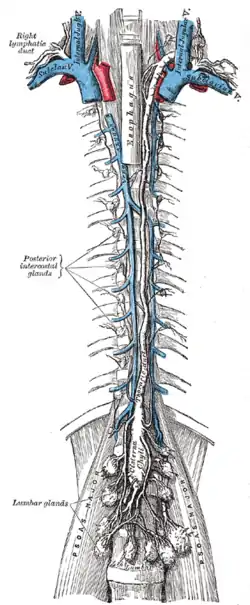

The thoracic and right lymphatic ducts. (Thoracic duct is thin vertical white line at center.) | |

Modes of origin of thoracic duct. (a) Thoracic duct. (a′) Cisterna chyli. (b), (c′) Efferent trunks from lateral aortic glands. (d) An efferent vessel which p... | |

| Details | |

| System | Lymphatic system |

| Source | cisterna chyli |

| Drains to | junction of the left subclavian vein and left internal jugular vein |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | ductus thoracicus |

| MeSH | D013897 |

| TA98 | A12.4.01.007 |

| TA2 | 5137 |

| FMA | 5031 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

When the duct ruptures, the resulting flood of liquid into the pleural cavity is known as chylothorax.

Structure

In adults, the thoracic duct is typically 38–45 cm in length and has an average diameter of about 5 mm. The vessel usually starts from the level of the twelfth thoracic vertebrae (T12) and extends to the root of the neck. It drains into the systemic (blood) circulation at the angle of the left subclavian and internal jugular veins as a single trunk, at the commencement of the brachiocephalic vein.[3][4]

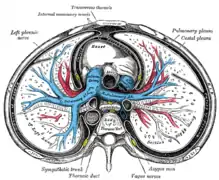

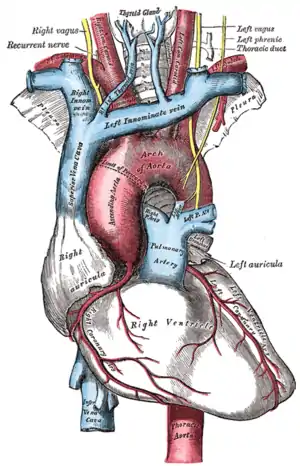

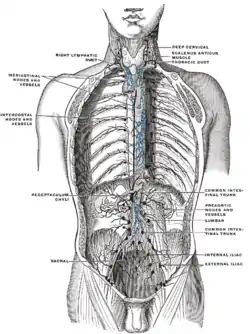

The thoracic duct originates in the abdomen from the confluence of the right and left lumbar trunks and the intestinal trunk, forming a significant pathway upward called the cisterna chyli.[5][6] It traverses the diaphragm at the aortic aperture, and ascends the superior and posterior mediastinum between the descending thoracic aorta (to its left) and the azygos vein (to its right).[5] The duct extends vertically in the chest and curves posteriorly to the left carotid artery and left internal jugular vein.[5][7] At the T5 vertebral level, it drains into the systemic (blood) circulation at the venous angle of the left subclavian and internal jugular veins as a single trunk, at the commencement of the brachiocephalic vein,[3][4] below the clavicle, near the shoulders.

Function

The thoracic duct collects most of the lymph in the body other than from the right thorax, arm, head, and neck.[7] These are drained by the right lymphatic duct.[1]

The lymph transport, in the thoracic duct, is mainly caused by the action of breathing, aided by the duct's smooth muscle and by internal valves which prevent the lymph from flowing back down again. There are also two valves at the junction of the duct with the left subclavian vein, to prevent the flow of venous blood into the duct. In adults, the thoracic duct transports up to 4 L of lymph per day.[8]

Clinical significance

The first sign of a malignancy, especially an intra-abdominal one, may be an enlarged Virchow's node, a lymph node in the left supraclavicular area, in the vicinity where the thoracic duct empties into the left brachiocephalic vein, right between where the left subclavian vein and left internal jugular join (i.e., the left Pirogoff angle). When the thoracic duct is blocked or damaged a large amount of lymph can quickly accumulate in the pleural cavity, this situation is called chylothorax.

Additional images

Transverse section of thorax, showing relations of pulmonary artery.

Transverse section of thorax, showing relations of pulmonary artery. The arch of the aorta, and its branches.

The arch of the aorta, and its branches. Deep lymph nodes and vessels of the thorax and abdomen (diagrammatic).

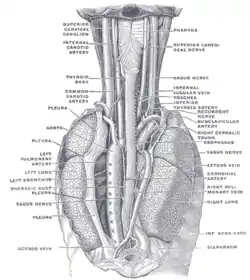

Deep lymph nodes and vessels of the thorax and abdomen (diagrammatic). The position and relation of the esophagus in the cervical region and in the posterior mediastinum. Seen from behind.

The position and relation of the esophagus in the cervical region and in the posterior mediastinum. Seen from behind. Front photo of the Ductus Thoracicus in the Human mediastinum with the heart and part of the pericard removed.

Front photo of the Ductus Thoracicus in the Human mediastinum with the heart and part of the pericard removed.

See also

References

- Schuenke, Michael; Schulte, Erik; Schumacher, Udo; Ross, Lawrence M.; Lamperti, Edward D.; Voll, Markus; Wesker, Karl (24 May 2006). Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: Neck and internal organs. Thieme. pp. 136ff. ISBN 978-3-13-142111-1. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- McLeod, Michael; Doherty, Gerard M. (1 January 2009), Evans, Stephen R. T. (ed.), "Chapter 40 - Thyroid Surgery", Surgical Pitfalls, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, pp. 397–405, doi:10.1016/b978-141602951-9.50051-7, ISBN 978-1-4160-2951-9, retrieved 18 November 2020

- Knipe, Henry. "Thoracic duct". Radiopaedia.org. Radiology Reference Article. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- Ellis, Harold; Insull, Phillip (1 October 2007). "Clinical Anatomy: Applied anatomy for students and junior doctors". ANZ Journal of Surgery (11th ed.). 77 (10): 911–912. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04191.x. ISSN 1445-2197. S2CID 70800205.

- Schipper, Paul; Sukumar, Mithran; Mayberry, John C. (1 January 2008), Asensio, JUAN A.; Trunkey, DONALD D. (eds.), "CHAPTER 33 - PERTINENT SURGICAL ANATOMY OF THE THORAX AND MEDIASTINUM", Current Therapy of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care, Philadelphia: Mosby, pp. 227–251, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-04418-9.50037-0, ISBN 978-0-323-04418-9, retrieved 18 November 2020

- Puligandla, Pramod S.; Laberge, Jean-Martin (1 January 2012), Coran, Arnold G. (ed.), "Chapter 66 - Infections and Diseases of the Lungs, Pleura, and Mediastinum", Pediatric Surgery (Seventh Edition), Philadelphia: Mosby, pp. 855–880, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-07255-7.00066-0, ISBN 978-0-323-07255-7, retrieved 18 November 2020

- Jacob, S. (1 January 2008), Jacob, S. (ed.), "Chapter 3 - Thorax", Human Anatomy, Churchill Livingstone, pp. 51–70, doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-10373-5.50006-3, ISBN 978-0-443-10373-5, retrieved 18 November 2020

- Tewfik, Ted L.; Mosenifar, Zab (7 December 2017). "Thoracic Duct Anatomy". Medscape. WebMD Health Professional Network.

External links

- Anatomy figure: 21:05-02 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center — "The thoracic duct and azygos venous network"

- Anatomy image:8901 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- figures/chapter_24/24-5.HTM: Basic Human Anatomy at Dartmouth Medical School

- "Ultrasound imaging the thoracic duct".

- "Instruction video for Ultrasound examination of the thoracic duct".