Smooth muscle

Smooth muscle is an involuntary non-striated muscle. It is divided into two subgroups; the single-unit (unitary) and multiunit smooth muscle. Within single-unit cells, the whole bundle or sheet contracts as a syncytium.

| Smooth muscle tissues | |

|---|---|

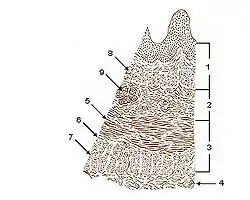

Layers of Esophageal Wall:

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | textus muscularis levis; textus muscularis nonstriatus |

| MeSH | D009130 |

| TH | H2.00.05.1.00001 |

| FMA | 14070 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Smooth muscle cells are found in the walls of hollow organs, including the stomach, intestines, urinary bladder and uterus, and in the walls of passageways, such as the arteries and veins of the circulatory system, and the tracts of the respiratory, urinary, and reproductive systems. In the eyes, the ciliary muscle, a type of smooth muscle, dilate and contract the iris and alter the shape of the lens. In the skin, smooth muscle cells cause hair to stand erect in response to cold temperature or fear.[1]

Structure

Most smooth muscle is of the single-unit variety, that is, either the whole muscle contracts or the whole muscle relaxes, but there is multiunit smooth muscle in the trachea, the large elastic arteries, and the iris of the eye. Single unit smooth muscle, however, is most common and lines blood vessels (except large elastic arteries), the urinary tract, and the digestive tract.

However, the terms single- and multi-unit smooth muscle represents an oversimplification. This is due to the fact that smooth muscles for the most part are controlled and influenced by a combination of different neural elements. In addition, it has been observed that most of the time there will be some cell to cell communication and activators/ inhibitors produced locally. This leads to a somewhat coordinated response even in multiunit smooth muscle.[2]

Smooth muscle is fundamentally different from skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle in terms of structure, function, regulation of contraction, and excitation-contraction coupling.

Smooth muscle cells known as myocytes, have a fusiform shape and, like striated muscle, can tense and relax. However, smooth muscle tissue tends to demonstrate greater elasticity and function within a larger length-tension curve than striated muscle. This ability to stretch and still maintain contractility is important in organs like the intestines and urinary bladder. In the relaxed state, each cell is spindle-shaped, 20–500 micrometers in length.

Molecular structure

A substantial portion of the volume of the cytoplasm of smooth muscle cells are taken up by the molecules myosin and actin,[3] which together have the capability to contract, and, through a chain of tensile structures, make the entire smooth muscle tissue contract with them.

Myosin

Myosin is primarily class II in smooth muscle.[4]

- Myosin II contains two heavy chains (MHC) which constitute the head and tail domains. Each of these heavy chains contains the N-terminal head domain, while the C-terminal tails take on a coiled-coil morphology, holding the two heavy chains together (imagine two snakes wrapped around each other, such as in a caduceus). Thus, myosin II has two heads. In smooth muscle, there is a single gene (MYH11[5]) that codes for the heavy chains myosin II, but there are splice variants of this gene that result in four distinct isoforms.[4] Also, smooth muscle may contain MHC that is not involved in contraction, and that can arise from multiple genes.[4]

- Myosin II also contains 4 light chains (MLC), resulting in 2 per head, weighing 20 (MLC20) and 17 (MLC17) kDa.[4] These bind the heavy chains in the "neck" region between the head and tail.

- The MLC20 is also known as the regulatory light chain and actively participates in muscle contraction.[4] Two MLC20 isoforms are found in smooth muscle, and they are encoded by different genes, but only one isoform participates in contraction.

- The MLC17 is also known as the essential light chain.[4] Its exact function is unclear, but it's believed that it contributes to the structural stability of the myosin head along with MLC20.[4] Two variants of MLC17 (MLC17a/b) exist as a result of alternative splicing at the MLC17 gene.[4]

Different combinations of heavy and light chains allow for up to hundreds of different types of myosin structures, but it is unlikely that more than a few such combinations are actually used or permitted within a specific smooth muscle bed.[4] In the uterus, a shift in myosin expression has been hypothesized to avail for changes in the directions of uterine contractions that are seen during the menstrual cycle.[4]

Actin

The thin filaments that are part of the contractile machinery are predominantly composed of α- and γ-actin.[4] Smooth muscle α-actin (alpha actin) is the predominant isoform within smooth muscle. There is also a lot of actin (mainly β-actin) that does not take part in contraction, but that polymerizes just below the plasma membrane in the presence of a contractile stimulant and may thereby assist in mechanical tension.[4] Alpha actin is also expressed as distinct genetic isoforms such as smooth muscle, cardiac muscle and skeletal muscle specific isoforms of alpha actin.[6]

The ratio of actin to myosin is between 2:1[4] and 10:1[4] in smooth muscle. Conversely, from a mass ratio standpoint (as opposed to a molar ratio), myosin is the dominant protein in striated skeletal muscle with the actin to myosin ratio falling in the 1:2 to 1:3 range. A typical value for healthy young adults is 1:2.2.[7][8][9][10]

Other proteins of the contractile apparatus

Smooth muscle does not contain the protein troponin; instead calmodulin (which takes on the regulatory role in smooth muscle), caldesmon and calponin are significant proteins expressed within smooth muscle.

- Tropomyosin is present in smooth muscle, spanning seven actin monomers and is laid out end to end over the entire length of the thin filaments. In striated muscle, tropomyosin serves to block actin–myosin interactions until calcium is present, but in smooth muscle, its function is unknown. [4]

- Calponin molecules may exist in equal number as actin, and has been proposed to be a load-bearing protein.[4]

- Caldesmon has been suggested to be involved in tethering actin, myosin and tropomyosin, and thereby enhance the ability of smooth muscle to maintain tension.[4]

Also, all three of these proteins may have a role in inhibiting the ATPase activity of the myosin complex that otherwise provides energy to fuel muscle contraction.[4]

Other tensile structures

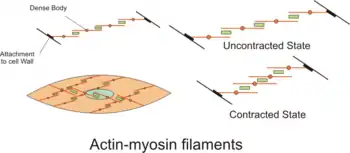

The myosin and actin are the contractile parts of continuous chains of tensile structures that stretch both across and between smooth muscle cells.

The actin filaments of contractile units are attached to dense bodies. Dense bodies are rich in α-actinin,[4] and also attach intermediate filaments (consisting largely of vimentin and desmin), and thereby appear to serve as anchors from which the thin filaments can exert force.[4] Dense bodies also are associated with β-actin, which is the type found in the cytoskeleton, suggesting that dense bodies may coordinate tensions from both the contractile machinery and the cytoskeleton.[4] Dense bodies appear darker under an electron microscope, and so they are sometimes described as electron dense.[11]

The intermediate filaments are connected to other intermediate filaments via dense bodies, which eventually are attached to adherens junctions (also called focal adhesions) in the cell membrane of the smooth muscle cell, called the sarcolemma. The adherens junctions consist of large number of proteins including α-actinin, vinculin and cytoskeletal actin.[4] The adherens junctions are scattered around dense bands that are circumfering the smooth muscle cell in a rib-like pattern.[3] The dense band (or dense plaques) areas alternate with regions of membrane containing numerous caveolae. When complexes of actin and myosin contract, force is transduced to the sarcolemma through intermediate filaments attaching to such dense bands.

During contraction, there is a spatial reorganization of the contractile machinery to optimize force development.[4] part of this reorganization consists of vimentin being phosphorylated at Ser56 by a p21 activated kinase, resulting in some disassembly of vimentin polymers.[4]

Also, the number of myosin filaments is dynamic between the relaxed and contracted state in some tissues as the ratio of actin to myosin changes, and the length and number of myosin filaments change.

Isolated single smooth muscle cells have been observed contracting in a spiral corkscrew fashion, and isolated permeabilized smooth muscle cells adhered to glass (so contractile proteins allowed to internally contract) demonstrate zones of contractile protein interactions along the long axis as the cell contracts.

Smooth muscle-containing tissue needs to be stretched often, so elasticity is an important attribute of smooth muscle. Smooth muscle cells may secrete a complex extracellular matrix containing collagen (predominantly types I and III), elastin, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans. Smooth muscle also has specific elastin and collagen receptors to interact with these proteins of the extracellular matrix. These fibers with their extracellular matrices contribute to the viscoelasticity of these tissues. For example, the great arteries are viscolelastic vessels that act like a Windkessel, propagating ventricular contraction and smoothing out the pulsatile flow, and the smooth muscle within the tunica media contributes to this property.

Caveolae

The sarcolemma also contains caveolae, which are microdomains of lipid rafts specialized to cell signaling events and ion channels. These invaginations in the sarcoplasm contain a host of receptors (prostacyclin, endothelin, serotonin, muscarinic receptors, adrenergic receptors), second messenger generators (adenylate cyclase, phospholipase C), G proteins (RhoA, G alpha), kinases (rho kinase-ROCK, protein kinase C, protein Kinase A), ion channels (L type calcium channels, ATP sensitive potassium channels, calcium sensitive potassium channels) in close proximity. The caveolae are often close to sarcoplasmic reticulum or mitochondria, and have been proposed to organize signaling molecules in the membrane.

Excitation-contraction coupling

A smooth muscle is excited by external stimuli, which causes contraction. Each step is further detailed below.

Inducing stimuli and factors

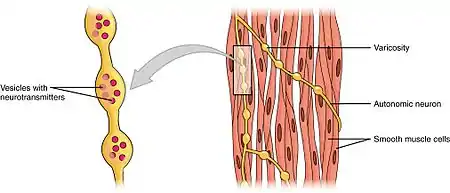

Smooth muscle may contract spontaneously (via ionic channel dynamics) or as in the gut special pacemakers cells interstitial cells of Cajal produce rhythmic contractions. Also, contraction, as well as relaxation, can be induced by a number of physiochemical agents (e.g., hormones, drugs, neurotransmitters – particularly from the autonomic nervous system).

Smooth muscle in various regions of the vascular tree, the airway and lungs, kidneys and vagina is different in their expression of ionic channels, hormone receptors, cell-signaling pathways, and other proteins that determine function.

External substances

For instance, blood vessels in skin, gastrointestinal system, kidney and brain respond to norepinephrine and epinephrine (from sympathetic stimulation or the adrenal medulla) by producing vasoconstriction (this response is mediated through alpha-1 adrenergic receptors). However, blood vessels within skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle respond to these catecholamines producing vasodilation because they possess beta-adrenergic receptors. So there is a difference in the distribution of the various adrenergic receptors that explains the difference in why blood vessels from different areas respond to the same agent norepinephrine/epinephrine differently as well as differences due to varying amounts of these catecholamines that are released and sensitivities of various receptors to concentrations.

Generally, arterial smooth muscle responds to carbon dioxide by producing vasodilation, and responds to oxygen by producing vasoconstriction. Pulmonary blood vessels within the lung are unique as they vasodilate to high oxygen tension and vasoconstrict when it falls. Bronchiole, smooth muscle that line the airways of the lung, respond to high carbon dioxide producing vasodilation and vasoconstrict when carbon dioxide is low. These responses to carbon dioxide and oxygen by pulmonary blood vessels and bronchiole airway smooth muscle aid in matching perfusion and ventilation within the lungs. Further different smooth muscle tissues display extremes of abundant to little sarcoplasmic reticulum so excitation-contraction coupling varies with its dependence on intracellular or extracellular calcium.

Recent research indicates that sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) signaling is an important regulator of vascular smooth muscle contraction. When transmural pressure increases, sphingosine kinase 1 phosphorylates sphingosine to S1P, which binds to the S1P2 receptor in plasma membrane of cells. This leads to a transient increase in intracellular calcium, and activates Rac and Rhoa signaling pathways. Collectively, these serve to increase MLCK activity and decrease MLCP activity, promoting muscle contraction. This allows arterioles to increase resistance in response to increased blood pressure and thus maintain constant blood flow. The Rhoa and Rac portion of the signaling pathway provides a calcium-independent way to regulate resistance artery tone.[12]

Spread of impulse

To maintain organ dimensions against force, cells are fastened to one another by adherens junctions. As a consequence, cells are mechanically coupled to one another such that contraction of one cell invokes some degree of contraction in an adjoining cell. Gap junctions couple adjacent cells chemically and electrically, facilitating the spread of chemicals (e.g., calcium) or action potentials between smooth muscle cells. Single unit smooth muscle displays numerous gap junctions and these tissues often organize into sheets or bundles which contract in bulk.

Contraction

Smooth muscle contraction is caused by the sliding of myosin and actin filaments (a sliding filament mechanism) over each other. The energy for this to happen is provided by the hydrolysis of ATP. Myosin functions as an ATPase utilizing ATP to produce a molecular conformational change of part of the myosin and produces movement. Movement of the filaments over each other happens when the globular heads protruding from myosin filaments attach and interact with actin filaments to form crossbridges. The myosin heads tilt and drag along the actin filament a small distance (10–12 nm). The heads then release the actin filament and then changes angle to relocate to another site on the actin filament a further distance (10–12 nm) away. They can then re-bind to the actin molecule and drag it along further. This process is called crossbridge cycling and is the same for all muscles (see muscle contraction). Unlike cardiac and skeletal muscle, smooth muscle does not contain the calcium-binding protein troponin. Contraction is initiated by a calcium-regulated phosphorylation of myosin, rather than a calcium-activated troponin system.

Crossbridge cycling causes contraction of myosin and actin complexes, in turn causing increased tension along the entire chains of tensile structures, ultimately resulting in contraction of the entire smooth muscle tissue.

Phasic or tonic

Smooth muscle may contract phasically with rapid contraction and relaxation, or tonically with slow and sustained contraction. The reproductive, digestive, respiratory, and urinary tracts, skin, eye, and vasculature all contain this tonic muscle type. This type of smooth muscle can maintain force for prolonged time with only little energy utilization. There are differences in the myosin heavy and light chains that also correlate with these differences in contractile patterns and kinetics of contraction between tonic and phasic smooth muscle.

Activation of myosin heads

Crossbridge cycling cannot occur until the myosin heads have been activated to allow crossbridges to form. When the light chains are phosphorylated, they become active and will allow contraction to occur. The enzyme that phosphorylates the light chains is called myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK), also called MLC20 kinase.[4] In order to control contraction, MLCK will work only when the muscle is stimulated to contract. Stimulation will increase the intracellular concentration of calcium ions. These bind to a molecule called calmodulin, and form a calcium-calmodulin complex. It is this complex that will bind to MLCK to activate it, allowing the chain of reactions for contraction to occur.

Activation consists of phosphorylation of a serine on position 19 (Ser19) on the MLC20 light chain, which causes a conformational change that increases the angle in the neck domain of the myosin heavy chain,[4] which corresponds to the part of the cross-bridge cycle where the myosin head is unattached to the actin filament and relocates to another site on it. After attachment of the myosin head to the actin filament, this serine phosphorylation also activates the ATPase activity of the myosin head region to provide the energy to fuel the subsequent contraction.[4] Phosphorylation of a threonine on position 18 (Thr18) on MLC20 is also possible and may further increase the ATPase activity of the myosin complex.[4]

Sustained maintenance

Phosphorylation of the MLC20 myosin light chains correlates well with the shortening velocity of smooth muscle. During this period there is a rapid burst of energy utilization as measured by oxygen consumption. Within a few minutes of initiation the calcium level markedly decrease, MLC20 myosin light chains phosphorylation decreases, and energy utilization decreases and the muscle can relax. Still, smooth muscle has the ability of sustained maintenance of force in this situation as well. This sustained phase has been attributed to certain myosin crossbridges, termed latch-bridges, that are cycling very slowly, notably slowing the progression to the cycle stage whereby dephosphorylated myosin detaches from the actin, thereby maintaining the force at low energy costs.[4] This phenomenon is of great value especially for tonically active smooth muscle.[4]

Isolated preparations of vascular and visceral smooth muscle contract with depolarizing high potassium balanced saline generating a certain amount of contractile force. The same preparation stimulated in normal balanced saline with an agonist such as endothelin or serotonin will generate more contractile force. This increase in force is termed calcium sensitization. The myosin light chain phosphatase is inhibited to increase the gain or sensitivity of myosin light chain kinase to calcium. There are number of cell signalling pathways believed to regulate this decrease in myosin light chain phosphatase: a RhoA-Rock kinase pathway, a Protein kinase C-Protein kinase C potentiation inhibitor protein 17 (CPI-17) pathway, telokin, and a Zip kinase pathway. Further Rock kinase and Zip kinase have been implicated to directly phosphorylate the 20kd myosin light chains.

Other contractile mechanisms

Other cell signaling pathways and protein kinases (Protein kinase C, Rho kinase, Zip kinase, Focal adhesion kinases) have been implicated as well and actin polymerization dynamics plays a role in force maintenance. While myosin light chain phosphorylation correlates well with shortening velocity, other cell signaling pathways have been implicated in the development of force and maintenance of force. Notably the phosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues on the focal adhesion adapter protein-paxillin by specific tyrosine kinases has been demonstrated to be essential to force development and maintenance. For example, cyclic nucleotides can relax arterial smooth muscle without reductions in crossbridge phosphorylation, a process termed force suppression. This process is mediated by the phosphorylation of the small heat shock protein, hsp20, and may prevent phosphorylated myosin heads from interacting with actin.

Relaxation

The phosphorylation of the light chains by MLCK is countered by a myosin light-chain phosphatase, which dephosphorylates the MLC20 myosin light chains and thereby inhibits contraction.[4] Other signaling pathways have also been implicated in the regulation actin and myosin dynamics. In general, the relaxation of smooth muscle is by cell-signaling pathways that increase the myosin phosphatase activity, decrease the intracellular calcium levels, hyperpolarize the smooth muscle, and/or regulate actin and myosin muscle can be mediated by the endothelium-derived relaxing factor-nitric oxide, endothelial derived hyperpolarizing factor (either an endogenous cannabinoid, cytochrome P450 metabolite, or hydrogen peroxide), or prostacyclin (PGI2). Nitric oxide and PGI2 stimulate soluble guanylate cyclase and membrane bound adenylate cyclase, respectively. The cyclic nucleotides (cGMP and cAMP) produced by these cyclases activate Protein Kinase G and Protein Kinase A and phosphorylate a number of proteins. The phosphorylation events lead to a decrease in intracellular calcium (inhibit L type Calcium channels, inhibits IP3 receptor channels, stimulates sarcoplasmic reticulum Calcium pump ATPase), a decrease in the 20kd myosin light chain phosphorylation by altering calcium sensitization and increasing myosin light chain phosphatase activity, a stimulation of calcium sensitive potassium channels which hyperpolarize the cell, and the phosphorylation of amino acid residue serine 16 on the small heat shock protein (hsp20)by Protein Kinases A and G. The phosphorylation of hsp20 appears to alter actin and focal adhesion dynamics and actin-myosin interaction, and recent evidence indicates that hsp20 binding to 14-3-3 protein is involved in this process. An alternative hypothesis is that phosphorylated Hsp20 may also alter the affinity of phosphorylated myosin with actin and inhibit contractility by interfering with crossbridge formation. The endothelium derived hyperpolarizing factor stimulates calcium sensitive potassium channels and/or ATP sensitive potassium channels and stimulate potassium efflux which hyperpolarizes the cell and produces relaxation.

Invertebrate smooth muscle

In invertebrate smooth muscle, contraction is initiated with the binding of calcium directly to myosin and then rapidly cycling cross-bridges, generating force. Similar to the mechanism of vertebrate smooth muscle, there is a low calcium and low energy utilization catch phase. This sustained phase or catch phase has been attributed to a catch protein that has similarities to myosin light-chain kinase and the elastic protein-titin called twitchin. Clams and other bivalve mollusks use this catch phase of smooth muscle to keep their shell closed for prolonged periods with little energy usage.

Specific effects

Although the structure and function is basically the same in smooth muscle cells in different organs, their specific effects or end-functions differ.

The contractile function of vascular smooth muscle regulates the lumenal diameter of the small arteries-arterioles called resistance vessels, thereby contributing significantly to setting the level of blood pressure and blood flow to vascular beds. Smooth muscle contracts slowly and may maintain the contraction (tonically) for prolonged periods in blood vessels, bronchioles, and some sphincters. Activating arteriole smooth muscle can decrease the lumenal diameter 1/3 of resting so it drastically alters blood flow and resistance. Activation of aortic smooth muscle doesn't significantly alter the lumenal diameter but serves to increase the viscoelasticity of the vascular wall.

In the digestive tract, smooth muscle contracts in a rhythmic peristaltic fashion, rhythmically forcing foodstuffs through the digestive tract as the result of phasic contraction.

A non-contractile function is seen in specialized smooth muscle within the afferent arteriole of the juxtaglomerular apparatus, which secretes renin in response to osmotic and pressure changes, and also it is believed to secrete ATP in tubuloglomerular regulation of glomerular filtration rate. Renin in turn activates the renin–angiotensin system to regulate blood pressure.

Growth and rearrangement

The mechanism in which external factors stimulate growth and rearrangement is not yet fully understood. A number of growth factors and neurohumoral agents influence smooth muscle growth and differentiation. The Notch receptor and cell-signaling pathway have been demonstrated to be essential to vasculogenesis and the formation of arteries and veins. The proliferation is implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and is inhibited by nitric oxide.

The embryological origin of smooth muscle is usually of mesodermal origin, after the creation of muscle fibers in a process known as myogenesis. However, the smooth muscle within the Aorta and Pulmonary arteries (the Great Arteries of the heart) is derived from ectomesenchyme of neural crest origin, although coronary artery smooth muscle is of mesodermal origin.

Related diseases

"Smooth muscle condition" is a condition in which the body of a developing embryo does not create enough smooth muscle for the gastrointestinal system. This condition is fatal.

Anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA) can be a symptom of an auto-immune disorder, such as hepatitis, cirrhosis, or lupus.

Tumors of smooth muscle are most commonly benign, and are then called leiomyomas. They can occur in any organ, but the most common forms occur in the uterus, small bowel, and the esophagus. Malignant smooth muscle tumors are called leiomyosarcomas. Leiomyosarcomas are one of the more common types of soft-tissue sarcomas. Vascular smooth muscle tumors are very rare. They can be malignant or benign, and morbidity can be significant with either type. Intravascular leiomyomatosis is a benign neoplasm that extends through the veins; angioleiomyoma is a benign neoplasm of the extremities; vascular leiomyosarcomas is a malignant neoplasm that can be found in the inferior vena cava, pulmonary arteries and veins, and other peripheral vessels. See Atherosclerosis.

See also

- Atromentin has been shown to be a smooth muscle stimulant.[13]

- Skeletal muscle

- Cardiac muscle

References

- "10.8 Smooth Muscle – Anatomy and Physiology". opentextbc.ca. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- Berne & Levy. Physiology, 6th Edition

- p. 174 in: The vascular smooth muscle cell: molecular and biological responses to the extracellular matrix. Authors: Stephen M. Schwartz, Robert P. Mecham. Editors: Stephen M. Schwartz, Robert P. Mecham. Contributors: Stephen M. Schwartz, Robert P. Mecham. Publisher: Academic Press, 1995. ISBN 0-12-632310-0, 978-0-12-632310-8

- Aguilar HN, Mitchell BF (2010). "Physiological pathways and molecular mechanisms regulating uterine contractility". Hum. Reprod. Update. 16 (6): 725–44. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq016. PMID 20551073.

- Matsuoka R, Yoshida MC, Furutani Y, Imamura S, Kanda N, Yanagisawa M, Masaki T, Takao A (1993). "Human smooth muscle myosin heavy chain gene mapped to chromosomal region 16q12". Am. J. Med. Genet. 46 (1): 61–67. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320460110. PMID 7684189.

- Perrin BJ, Ervasti JM (2010). "The actin gene family: function follows isoform". Cytoskeleton. 67 (10): 630–34. doi:10.1002/cm.20475. PMC 2949686. PMID 20737541.

- Aguilar_2010 (above reference) "In skeletal or striated muscle, there is 3-fold more myosin than actin."

- Trappe S, Gallagher P, et al. Single muscle fibre contractile properties in young and old men and women. J Physiol (2003), 552.1, pp. 47–58, Table 8

- Greger R, Windhorst U; Comprehensive Human Physiology, Vol. II. Berlin, Springer, 1996; Chapter 46, Table 46.1, Myosin 45%, Actin 22% of skeletal muscle myofibrillar proteins, p. 937

- Lawrie's Meat Science, Lawrie RA, Ledward, D; 2014; Chapter 4, Table 4.1, Chemical Composition of Typical Mammalian Adult Muscle, percent of skeletal muscle tissue wet weight; myosin 5.5%, actin 2.5%, p. 76

- Ultrastructure of Smooth Muscle, Volume 8 of Electron Microscopy in Biology and Medicine, Editor P. Motta, Springer Science & Business Media, 2012, ISBN 1461306833, 9781461306832. (p. 163 Archived 2017-05-10 at the Wayback Machine)

- Scherer EQ, Lidington D, Oestreicher E, Arnold W, Pohl U, Bolz SS (2006). "Sphingosine-1-phosphate modulates spiral modiolar artery tone: A potential role in vascular-based inner ear pathologies?". Cardiovasc. Res. 70 (1): 79–87. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.01.011. PMID 16533504.

- Sullivan G, Guess WL (1969). "Atromentin: a smooth muscle stimulant in Clitocybe subilludens". Lloydia. 32 (1): 72–75. PMID 5815216.

External links

- BBC – baby born with smooth muscle condition has 8 organs transplanted

- Smooth muscle antibody

- Stomach smooth muscle identified using antibody

- UIUC Histology Subject 265

- Histology at KUMC muscular-muscle08 "Smooth Muscle"

- Histology image: 21701ooa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Smooth muscle histology photomicrographs

- Where smooth muscle tissue is found in the body (medlineplus.gov)