Tomb of Menecrates

The Tomb of Menecrates or Monument of Menecrates is an Archaic-period cenotaph in Corfu, Greece, built around 600 BC in the ancient city of Korkyra (or Corcyra).[1][2] The tomb and the funerary sculpture of a lion were discovered in 1843 during demolition works by the British army who were demolishing a Venetian-era fortress in the site of Garitsa hill in Corfu.[3] The tomb is dated to the sixth century BC.[3]

The sculpture is dated to the end of the seventh century BC and is one of the earliest funerary lions ever found.[3] The tomb and the sculpture were found in an area that was part of the necropolis of ancient Korkyra, which was discovered by the British army at the time.[3] According to an Ancient Greek inscription found on the grave, the tomb was a monument built by the ancient Korkyreans in honour of their proxenos (ambassador) Menecrates, son of Tlasias, from Oiantheia. Menecrates was the ambassador of ancient Korkyra to Oiantheia (modern-day Galaxidi) or Ozolian Locris,[4][5] and he was lost at sea,[6] perhaps in a sea battle.[7] The inscription also mentions that Praximenes, the brother of Menecrates, had arrived from Oiantheia to assist the people of Korkyra in building the monument to his brother.[6][1]

Dating and construction

_03.jpg.webp)

Both the tomb and the sculpture are made of local limestone.[3] The tomb is cylindrical with a conical roof.[3] The cylindrical part consists of five circular rings (or domes) made of stones of equal thickness featuring isodomic construction.[6] The conical cover of the tomb is similar to the original one (which has disappeared), and it features stones radiating from a central rectangular capstone at the top.[6] The monument is 1.4 m (4 ft 7 in) in height[8] and 4.7–4.9 m (15–16 ft) in diameter.[8][4] The tomb represents a significantly better example of funerary architecture than the primitive tomb forms available at that time.[9]

Due to the softness of the stones, the monument shows signs of significant weathering and erosion.[6] The tomb is more precisely dated to 570–540 BC.[6] There are only two monuments of this kind in Greece, the other being the undated monument to Kleoboulos in Rhodes.[6]

Inscription

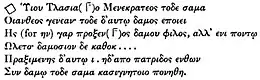

There is an ancient inscription on the tomb. It is expressed in dactylic hexameter,[3] and is written in the Corinthian alphabet from right to left. It starts with a mark of a rhombus, and there are traces of punctuation marks.[3][10] Its style is very early, as indicated by the use of the digamma Ϝ.[10] The inscription is one of the oldest extant in Greece.[6] There is a peculiarity in the inscription, in that although it is in Doric Greek, the verb "πονηθη" is in Ionian Greek; the proper Doric form should have been "ποναθη".[10] It is theorised that while the authors of the inscription were Dorians, the inscription on the tomb must have been engraved by an Ionian.[10]

The inscription reads as follows:[10][11][12]

Υιού Τλασίαο Μενεκράτους τόδε σάμα Οιανθέως γενεάν τόδε δ' αυτώ δάμος εποίει- Ης γαρ πρόξενος, δάμου φίλος- αλλ' ενίπόντω Ώλετο· δαμόσιον δε καθίκετο πένθος Οιάνθην. Πραξιμενης δ' αυτώ ι. ηδ' απο πατριδος ενθων Συν δαμω τοδε σαμα κασιγνητοιο πονηθη.

The ancient inscription translates as:

For Menecrates, the son of Tlasias from Oiantheia, this [monument] was built by the people [of Korkyra]—because he was proxenos [ambassador] and friend of the people [of Korkyra], but he was lost at sea. Oiantheia fell into public mourning. Praximenes for this reason came from his fatherland to make an effort to raise this monument to his brother together with the people [of Korkyra].[3][10]

Lion of Menecrates

.jpg.webp)

The sculpture of the Lion of Menecrates was found near the tomb and was thought to belong to the cenotaph of Menecrates, from whom it got its name.[3][13] The sculpture is of Assyrian sculptural style, and it is considered to be an excellent example of Archaic-period sculpture.[3] The sculpture is dated to the end of the seventh century BC and it is one of the earliest funerary lions ever found.[3] The sculpture is exhibited at the Archaeological Museum of Corfu.[3][6] There also is speculation, however, that the sculpture might belong to the tomb of Arniadas.[1]

Conservation and administration

A study for the conservation and repair of the monument has been approved by the Central Archaeological Council. The council also accepted the advice of a professor at the National Technical University of Athens to modify the proposal to include measures for avoiding flooding at the base of the monument, by creating a sloping surface at the foundation.[8]

In September 2018, both the mayor of Corfu and regional governor of the Ionian Islands Region sent protest letters to the Greek Minister of Finance, objecting to plans by the Greek government to administer the Tomb of Menecrates and other archaeological monuments of Corfu through the Hellenic Holding and Property Company (Ελληνική Εταιρεία Συμμετοχών και Περιουσίας) and the Greek Public Properties Company S.A. (Εταιρία Ακινήτων Δημοσίου Α.Ε.), also known as Superfund.[14][15]

References

- Percy Gardner (1896). Sculptured Tombs of Hellas. Macmillan and Company, Limited. p. 200.

- Luca Di Lorenzo (9 May 2018). Corfù - La guida di isole-greche.com. Luca Di Lorenzo. p. 205. ISBN 978-88-283-2151-4.

- "Funerary Archaic Lion". Archaeological Museum of Corfu.

- Nick Fisher; Hans van Wees (31 December 1998). Archaic Greece: New Approaches and New Evidence. Classical Press of Wales. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-910589-58-8.

- Germain Bazin (1976). The History of World Sculpture. Chartwell Books. p. 127.

This lion was found near the tomb of Menekrates in the necropolis of ancient Kerkyra (modern Corfu). Menekrates was a Lokrian, the proxenos of the people of Kerkyra, according to a metric inscription on the grave monument.

- "Το μνημείο του Μενεκράτη". Odysseus.

- The Building News and Engineering Journal. 1883. p. 722.

- "Υπέρ του μνημείου Μενεκράτη στην Κέρκυρα το ΚΑΣ". Newsbeast. 13 January 2011.

- Alan Rowe; Derek Buttle. Cyrenaican Expedition. Manchester University Press. p. 11. GGKEY:KF16Y6P8CQS.

- The Journal of the British Archaeological Association. British Archaeological Association. 1856. p. 23.

- The Literary Gazette and Journal of the Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, &c. W.A. Scripps. 1843. p. 853.

- Thanasēs Gkonēs (1999). Poreia gia Galaxidi. Ekdoseis Gkonē. p. 28.

Υιού Τλασίαο Μενεκράτεος τόδε σάμα Οιανθέως γενεάν τόδε δ' αυτώ δάμος εποίει - Ης γαρ πρόξενος, δάμου φίλος- αλλ' ενίπόντω Ώλετο· δαμόσιον δε καθίκετο πένθος Οιάνθην.

- Richard Norton (1897). Greek Grave-reliefs. Ginn & Company. p. 43.

- "Επιστολή Νικολούζου για τα μνημεία της Κέρκυρας". ERT. 26 September 2018.

- "Δήμαρχος Κέρκυρας: «Δεν πουλάμε τα μνημεία μας, ανακαλέστε»". Enimerosi. 25 September 2018.

External links

Media related to Tomb of Menekrates at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tomb of Menekrates at Wikimedia Commons