Trematoda

Trematoda is a class within the phylum Platyhelminthes. It includes two groups of parasitic flatworms, known as flukes.

| Trematoda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Botulus microporus, a giant digenean parasite from the intestine of a lancetfish | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Rhabditophora |

| Superorder: | Neodermata |

| Clade: | Trematoda Rudolphi, 1808 |

| Subclasses | |

They are internal parasites of molluscs and vertebrates. Most trematodes have a complex life cycle with at least two hosts. The primary host, where the flukes sexually reproduce, is a vertebrate. The intermediate host, in which asexual reproduction occurs, is usually a snail.

Taxonomy and biodiversity

The trematodes or flukes include 18,000[1] to 24,000[2] species, divided into two subclasses. Nearly all trematodes are parasites of mollusks and vertebrates. The smaller Aspidogastrea, comprising about 100 species, are obligate parasites of mollusks and may also infect turtles and fish, including cartilaginous fish. The Digenea, the majority of trematodes, are obligate parasites of both mollusks and vertebrates, but rarely occur in cartilaginous fish.

Two other parasitic classes, the Monogenea and Cestoda, are sister classes in the Neodermata, a group of Rhabditophoran Platyhelminthes.[3]

Anatomy

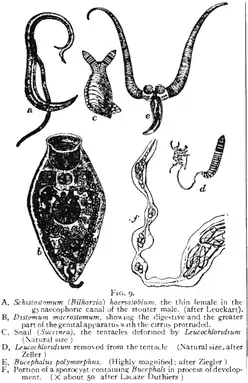

Trematodes are flattened oval or worm-like animals, usually no more than a few centimetres in length, although species as small as 1 millimetre (0.039 in) are known. Their most distinctive external feature is the presence of two suckers, one close to the mouth, and the other on the underside of the animal.[4]

The body surface of trematodes comprises a tough syncitial tegument, which helps protect against digestive enzymes in those species that inhabit the gut of larger animals. It is also the surface of gas exchange; there are no respiratory organs.[4]

The mouth is located at the forward end of the animal, and opens into a muscular, pumping pharynx. The pharynx connects, via a short oesophagus, to one or two blind-ending caeca, which occupy most of the length of the body. In some species, the caeca are themselves branched. As in other flatworms, there is no anus, and waste material must be egested through the mouth.[4]

Although the excretion of nitrogenous waste occurs mostly through the tegument, trematodes do possess an excretory system, which is instead mainly concerned with osmoregulation. This consists of two or more protonephridia, with those on each side of the body opening into a collecting duct. The two collecting ducts typically meet up at a single bladder, opening to the exterior through one or two pores near the posterior end of the animal.[4]

The brain consists of a pair of ganglia in the head region, from which two or three pairs of nerve cords run down the length of the body. The nerve cords running along the ventral surface are always the largest, while the dorsal cords are present only in the Aspidogastrea. Trematodes generally lack any specialised sense organs, although some ectoparasitic species do possess one or two pairs of simple ocelli.[4]

Reproductive system

Most trematodes are simultaneous hermaphrodites, having both male and female organs. There are usually two testes, with sperm ducts that join together on the underside of the front half of the animal. This final part of the male system varies considerably in structure between species, but may include sperm storage sacs and accessory glands, in addition to the copulatory organ, which is either eversible, and termed a cirrus, or non-eversible, and termed a penis.[4]

There is usually only a single ovary. Eggs pass from it into an oviduct. The distal part of the oviduct, called ootype, is dilated. It is connected via a pair of ducts to a number of vitelline glands on either side of the body, that produce yolk cells. After the egg is surrounded by yolk cells, its shell is formed from the secretion of another gland called Mehlis' gland or shell gland, the duct of which also opens in the ootype.

The ootype is connected to an elongated uterus that opens to the exterior in the genital pore, close to the male opening. In most trematodes, sperm cells travel through the uterus to reach the ootype, where fertilization occurs. The ovary is sometimes also associated with a storage sac for sperm, and a copulatory duct termed Laurer's canal.[4]

Life cycles

Almost all trematodes infect molluscs as the first host in the life cycle, and most have a complex life cycle involving other hosts. Most trematodes are monoecious and alternately reproduce sexually and asexually. The two main exceptions to this are the Aspidogastrea, which have no asexual reproduction, and the schistosomes, which are dioecious.

In the definitive host, in which sexual reproduction occurs, eggs are commonly shed along with host feces. Eggs shed in water release free-swimming larval forms that are infective to the intermediate host, in which asexual reproduction occurs.

A species that exemplifies the remarkable life history of the trematodes is the bird fluke, Leucochloridium paradoxum. The definitive hosts, in which the parasite reproduces, are various woodland birds, while the hosts in which the parasite multiplies (intermediate host) are various species of snail. The adult parasite in the bird's gut produces eggs and these eventually end up on the ground in the bird's faeces. Some eggs may be swallowed by a snail and hatch into larvae (miracidia). These larvae grow and take on a sac-like appearance. This stage is known as the sporocyst and it forms a central body in the snail's digestive gland that extends into a brood sac in the snail's head, muscular foot and eye-stalks. It is in the central body of the sporocyst where the parasite replicates itself, producing many tiny embryos (redia). These embryos move to the brood sac and mature into cercaria.

Life cycle adaptations

Trematodes have a large variation of forms throughout their life cycles. Individual trematode parasites life cycles may vary from this list.

- Trematodes are released from the definitive host as eggs, which have evolved to withstand the harsh environment

- Released from the egg is the miracidium. This infects the first intermediate host in one of two ways, either active or passive transmission. a) Active transmission has adapted for dispersal in space as a free swimming ciliated miricidium with adaptations for recognising and penetrating the first intermediate host. b) Passive transmission has adapted for dispersal in time and infects the first intermediate host contained within the egg.

- The sporocyst forms inside the snail first intermediate host and feeds through diffusion across the tegument.

- The rediae also forms inside the snail first intermediate host and feeds through a developed pharynx. Either the rediae or the sporocyst develops into the cercariae through polyembryony in the snail.

- The cercariae are adapted for dispersal in space and exhibit a large variety in morphology. They are adapted to recognise and penetrate the second intermediate host, and contain behavioural and physiological adaptations not present in earlier life stages.

- The metacercariae are an adapted cystic form dormant in the secondary intermediate host.

- The adult is the fully developed form which infects the definitive host.

Infections

Human infections are most common in Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Middle East. However, trematodes can be found anywhere where untreated human waste is used as fertilizer.Schistosomiasis (also known as bilharzia, bilharziosis or snail fever) is an example of a parasitic disease caused by one of the species of trematodes (platyhelminth infection, or "flukes"), a parasitic worm of the genus Schistosoma. Clonorchis, Opisthorchis, Fasciola and Paragonimus species, the foodborne trematodes, are another. Other diseases are caused by members of the genus Choledocystus.

Etymology

Trematodes are commonly referred to as flukes. This term can be traced back to the Old English name for flounder, and refers to the flattened, rhomboidal shape of the worms.

The flukes can be classified into two groups, on the basis of the system which they infect in the vertebrate host.

- Tissue flukes infect the bile ducts, lungs, or other biological tissues. This group includes the lung fluke, Paragonimus westermani, and the liver flukes, Clonorchis sinensis and Fasciola hepatica.

- Blood flukes inhabit the blood in some stages of their life cycle. Blood flukes include species of the genus Schistosoma.

They may also be classified according to the environment in which they are found. For instance, pond flukes infect fish in ponds.[5]

References

- Littlewood D T J; Bray R. A. (2000). "The Digenea". Interrelationships of the Platyhelminthes. Systematics Association Special Volume. 60 (1 ed.). CRC. pp. 168–185. ISBN 978-0-7484-0903-7.

- Poulin, Robert; Serge Morand (2005). Parasite Biodiversity. Smithsonian. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-58834-170-9.

- Willems, W. R.; Wallberg, A.; Jondelius, U.; et al. (November 2005). "Filling a gap in the phylogeny of flatworms: relationships within the Rhabdocoela (Platyhelminthes), inferred from 18S ribosomal DNA sequences" (PDF). Zoologica Scripta. 35 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2005.00216.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 230–235. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- Examples of the use of this term:

- "Pond Fluke Tabs-20ct". Pet Mountain. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- "AP Pond Fluke - 20 pk". That Fish Place - That Pet Place. Retrieved 28 June 2008.