Helminthiasis

Helminthiasis, also known as worm infection, is any macroparasitic disease of humans and other animals in which a part of the body is infected with parasitic worms, known as helminths. There are numerous species of these parasites, which are broadly classified into tapeworms, flukes, and roundworms. They often live in the gastrointestinal tract of their hosts, but they may also burrow into other organs, where they induce physiological damage.

| Helminthiasis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Worm infection, helminthosis, helminthiases, helminth infection |

_(16424840021).jpg.webp) | |

| Ascaris worms (one type of helminth) in the small bowel of an infected person (X-ray image with barium as contrast medium) | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

Soil-transmitted helminthiasis and schistosomiasis are the most important helminthiases, and are among the neglected tropical diseases.[1] This group of helmianthiases have been targeted under the joint action of the world's leading pharmaceutical companies and non-governmental organizations through a project launched in 2012 called the London Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases, which aims to control or eradicate certain neglected tropical diseases by 2020.[2]

Helminthiasis has been found to result in poor birth outcome, poor cognitive development, poor school and work performance, poor socioeconomic development, and poverty.[3][4] Chronic illness, malnutrition, and anemia are further examples of secondary effects.[5]

Soil-transmitted helminthiases are responsible for parasitic infections in as much as a quarter of the human population worldwide.[6] One well-known example of soil-transmitted helminthiases is ascariasis.

Signs and symptoms

_(15806559913).jpg.webp)

The signs and symptoms of helminthiasis depend on a number of factors including: the site of the infestation within the body; the type of worm involved; the number of worms and their volume; the type of damage the infesting worms cause; and, the immunological response of the body. Where the burden of parasites in the body is light, there may be no symptoms.

Certain worms may cause particular constellations of symptoms. For instance, taeniasis can lead to seizures due to neurocysticercosis.[7]

Mass and volume

In extreme cases of intestinal infestation, the mass and volume of the worms may cause the outer layers of the intestinal wall, such as the muscular layer, to tear. This may lead to peritonitis, volvulus, and gangrene of the intestine.[8]

Immunological response

As pathogens in the body, helminths induce an immune response. Immune-mediated inflammatory changes occur in the skin, lung, liver, intestine, central nervous system, and eyes. Signs of the body's immune response may include eosinophilia, edema, and arthritis.[9] An example of the immune response is the hypersensitivity reaction that may lead to anaphylaxis. Another example is the migration of Ascaris larvae through the bronchi of the lungs causing asthma.[10]

Secondary effects

Immune changes

In humans, T helper cells and eosinophils respond to helminth infestation. Inflammation leads to encapsulation of egg deposits throughout the body. Helminths excrete into the intestine toxic substances after they feed. These substances then enter the circulatory and lymphatic systems of the host body.

Chronic immune responses to helminthiasis may lead to increased susceptibility to other infections such as tuberculosis, HIV, and malaria.[11][12][13] There is conflicting information about whether deworming reduces HIV progression and viral load and increases CD4 counts in antiretroviral naive and experienced individuals, although the most recent Cochrane review found some evidence that this approach might have favorable effects.[14][15]

Chronic illness

Chronic helminthiasis may cause severe morbidity.[16] Helminthiasis has been found to result in poor birth outcome, poor cognitive development, poor school and work performance, decreased productivity, poor socioeconomic development, and poverty.[3][4][5]

Malnutrition

Helminthiasis may cause chronic illness through malnutrition including vitamin deficiencies, stunted growth, anemia, and protein-energy malnutrition. Worms compete directly with their hosts for nutrients, but the magnitude of this effect is likely minimal as the nutritional requirements of worms is relatively small.[17][18][19] In pigs and humans, Ascaris has been linked to lactose intolerance and vitamin A, amino acid, and fat malabsorption.[3] Impaired nutrient uptake may result from direct damage to the intestinal mucosal wall or from more subtle changes such as chemical imbalances and changes in gut flora.[20] Alternatively, the worms’ release of protease inhibitors to defend against the body's digestive processes may impair the breakdown of other nutrients.[17][19] In addition, worm induced diarrhoea may shorten gut transit time, thus reducing absorption of nutrients.[3]

Malnutrition due to worms can give rise to anorexia.[18] A study of 459 children in Zanzibar revealed spontaneous increases in appetite after deworming.[21] Anorexia might be a result of the body's immune response and the stress of combating infection.[19] Specifically, some of the cytokines released in the immune response to worm infestation have been linked to anorexia in animals.[17]

Anemia

Helminths may cause iron-deficiency anemia. This is most severe in heavy hookworm infections, as Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale feed directly on the blood of their hosts. Although the daily consumption of an individual worm (0.02–0.07 ml and 0.14–0.26 ml respectively) is small, the collective consumption under heavy infection can be clinically significant.[3][19] Intestinal whipworm may also cause anemia. Anemia has also been associated with reduced stamina for physical labor, a decline in the ability to learn new information, and apathy, irritability, and fatigue.[3] A study of the effect of deworming and iron supplementation in 47 students from the Democratic Republic of the Congo found that the intervention improved cognitive function.[22] Another study found that in 159 Jamaican schoolchildren, deworming led to better auditory short-term memory and scanning and retrieval of long-term memory over a period of nine-weeks.[23]

Cognitive changes

Malnutrition due to helminths may affect cognitive function leading to low educational performance, decreased concentration and difficulty with abstract cognitive tasks. Iron deficiency in infants and preschoolers is associated with "lower scores ... on tests of mental and motor development ... [as well as] increased fearfulness, inattentiveness, and decreased social responsiveness".[17] Studies in the Philippines and Indonesia found a significant correlation between helminthiasis and decreased memory and fluency.[24][25] Large parasite burdens, particularly severe hookworm infections, are also associated with absenteeism, under-enrollment, and attrition in school children.[17]

Helminths types causing infections

Of all the known helminth species, the most important helminths with respect to understanding their transmission pathways, their control, inactivation and enumeration in samples of human excreta from dried feces, faecal sludge, wastewater, and sewage sludge are:[26]

- soil-transmitted helminths, including Ascaris lumbricoides (the most common worldwide), Trichuris trichiura, Necator americanus, Strongyloides stercoralis and Ancylostoma duodenale

- Hymenolepis nana

- Taenia saginata

- Enterobius

- Fasciola hepatica

- Schistosoma mansoni

- Toxocara canis

- Toxocara cati

Helminthiases are classified as follows (the disease names end with "-sis" and the causative worms are in brackets):

Roundworm infection (nematodiasis)

- Filariasis (Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi infection)

- Onchocerciasis (Onchocerca volvulus infection)

- Soil-transmitted helminthiasis – this includes ascariasis (Ascaris lumbricoides infection, trichuriasis (Trichuris infection), and hookworm infection (includes necatoriasis and Ancylostoma duodenale infection)

- Trichostrongyliasis (Trichostrongylus spp. infection)

- Dracunculiasis (guinea worm infection)

- Baylisascaris (raccoon roundworm, may be transmitted to pets livestock and humans)

Tapeworm infection (cestodiasis)

- Echinococcosis (Echinococcus infection)

- Hymenolepiasis (Hymenolepis infection)

- Taeniasis/cysticercosis (Taenia infection)

- Coenurosis (T. multiceps, T. serialis, T. glomerata, and T. brauni infection)

Trematode infection (trematodiasis)

- Amphistomiasis (amphistomes infection)

- Clonorchiasis (Clonorchis sinensis infection)

- Fascioliasis (Fasciola infection)

- Fasciolopsiasis (Fasciolopsis buski infection)

- Opisthorchiasis (Opisthorchis infection)

- Paragonimiasis (Paragonimus infection)

- Schistosomiasis/bilharziasis (Schistosoma infection)

Acanthocephala infection

- Moniliformis infection

Transmission

Helminths are transmitted to the final host in several ways. The most common infection is through ingestion of contaminated vegetables, drinking water, and raw or undercooked meat. Contaminated food may contain eggs of nematodes such as Ascaris, Enterobius, and Trichuris; cestodes such as Taenia, Hymenolepis, and Echinococcus; and trematodes such as Fasciola. Raw or undercooked meats are the major sources of Taenia (pork, beef and venison), Trichinella (pork and bear), Diphyllobothrium (fish), Clonorchis (fish), and Paragonimus (crustaceans). Schistosomes and nematodes such as hookworms (Ancylostoma and Necator) and Strongyloides can penetrate the skin directly. Finally, Wuchereria, Onchocerca, and Dracunculus are transmitted by mosquitoes and flies.[16] In the developing world, the use of contaminated water is a major risk factor for infection.[27] Infection can also take place through the practice of geophagy, which is not uncommon in parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Soil is eaten, for example, by children or pregnant women to counteract a real or perceived deficiency of minerals in their diet.[28]

Diagnosis

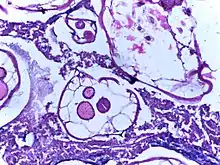

Specific helminths can be identified through microscopic examination of their eggs (ova) found in faecal samples. The number of eggs is measured in units of eggs per gram.[29] However, it does not quantify mixed infections, and in practice, is inaccurate for quantifying the eggs of schistosomes and soil-transmitted helminths.[30] Sophisticated tests such as serological assays, antigen tests, and molecular diagnosis are also available;[29][31] however, they are time-consuming, expensive and not always reliable.[32]

Prevention

Disrupting the cycle of the worm will prevent infestation and re-infestation. Prevention of infection can largely be achieved by addressing the issues of WASH—water, sanitation and hygiene.[33][34][35] The reduction of open defecation is particularly called for,[36][37] as is stopping the use of human waste as fertilizer.[6]

Further preventive measures include adherence to appropriate food hygiene, wearing of shoes, regular deworming of pets, and the proper disposal of their feces.[3]

Scientists are also searching for a vaccine against helminths, such as a hookworm vaccine.[38]

Treatment

Medications

Broad-spectrum benzimidazoles (such as albendazole and mebendazole) are the first line treatment of intestinal roundworm and tapeworm infections. Macrocyclic lactones (such as ivermectin) are effective against adult and migrating larval stages of nematodes. Praziquantel is the drug of choice for schistosomiasis, taeniasis, and most types of food-borne trematodiases. Oxamniquine is also widely used in mass deworming programmes. Pyrantel is commonly used for veterinary nematodiasis.[39][40] Artemisinins and derivatives are proving to be candidates as drugs of choice for trematodiasis.[41]

Mass deworming

In regions where helminthiasis is common, mass deworming treatments may be performed, particularly among school-age children, who are a high-risk group.[42][43] Most of these initiatives are undertaken by the World Health Organization (WHO) with positive outcomes in many regions.[44][45] Deworming programs can improve school attendance by 25 percent.[46] Although deworming improves the health of an individual, outcomes from mass deworming campaigns, such as reduced deaths or increases in cognitive ability, nutritional benefits, physical growth, and performance, are uncertain or not apparent.[47][48][49][50]

Surgery

_(15806559973).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

If complications of helminthiasis, such as intestinal obstruction occur, emergency surgery may be required.[8][51] Patients who require non-emergency surgery, for instance for removal of worms from the biliary tree, can be pre-treated with the anthelmintic drug albendazole.[8]

Epidemiology

Areas with the highest prevalence of helminthiasis are tropical and subtropical areas including sub-Saharan Africa, central and east Asia, and the Americas.

Neglected tropical diseases

Some types of helminthiases are classified as neglected tropical diseases.[1][52] They include:

- Soil-transmitted helminthiases

- Roundworm infections such as lymphatic filariasis, dracunculiasis, and onchocerciasis

- Trematode infections, such as schistosomiasis, and food-borne trematodiases, including fascioliasis, clonorchiasis, opisthorchiasis, and paragonimiasis

- Tapeworm infections such as cysticercosis, taeniasis, and echinococcosis

Prevalence

The soil-transmitted helminths (A. lumbricoides, T. trichiura, N. americanus, A. duodenale), schistosomes, and filarial worms collectively infect more than a quarter of the human population worldwide at any one time, far surpassing HIV and malaria together.[29][31] Schistosomiasis is the second most prevalent parasitic disease of humans after malaria.[53]

In 2014–15, the WHO estimated that approximately 2 billion people were infected with soil-transmitted helminthiases,[6] 249 million with schistosomiasis,[54] 56 million people with food-borne trematodiasis,[55] 120 million with lymphatic filariasis,[56] 37 million people with onchocerciasis,[57] and 1 million people with echinococcosis.[58] Another source estimated a much higher figure of 3.5 billion infected with one or more soil-transmitted helminths.[59][60]

In 2014, only 148 people were reported to have dracunculiasis because of a successful eradication campaign for that particular helminth, which is easier to eradicate than other helminths as it is transmitted only by drinking contaminated water.[61]

Because of their high mobility and lower standards of hygiene, school-age children are particularly vulnerable to helminthiasis.[62] Most children from developing nations will have at least one infestation. Multi-species infections are very common.[63]

The most common intestinal parasites in the United States are Enterobius vermicularis, Giardia lamblia, Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus, and Entamoeba histolytica.[64]

Variations within communities

Even in areas of high prevalence, the frequency and severity of infection is not uniform within communities or families.[65] A small proportion of community members harbour the majority of worms, and this depends on age. The maximum worm burden is at five to ten years of age, declining rapidly thereafter.[66] Individual predisposition to helminthiasis for people with the same sanitation infrastructure and hygiene behavior is thought to result from differing immunocompetence, nutritional status, and genetic factors.[65] Because individuals are predisposed to a high or a low worm burden, the burden reacquired after successful treatment is proportional to that before treatment.[65]

Disability-adjusted life years

It is estimated that intestinal nematode infections cause 5 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYS) to be lost, of which hookworm infections account for more than 3 million DALYS and ascaris infections more than 1 million.[67] There are also signs of progress: The Global Burden of Disease Study published in 2015 estimates a 46 percent (59 percent when age standardised) reduction in years lived with disability (YLD) for the 13-year time period from 1990 to 2013 for all intestinal/nematode infections, and even a 74 percent (80 percent when age standardised) reduction in YLD from ascariasis.[68]

Deaths

As many as 135,000 die annually from soil transmitted helminthiasis.[3][69][70]

The 1990–2013 Global Burden of Disease Study estimated 5,500 direct deaths from schistosomiasis,[71] while more than 200,000 people were estimated in 2013 to die annually from causes related to schistosomiasis.[72] Another 20 million have severe consequences from the disease.[73] It is the most deadly of the neglected tropical diseases.[74]

| Helminth genera | Common name | Infections (million per year) | Direct deaths per year | Regions where common | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil transmitted helminthiasis (STH) (classified as neglected tropical disease): | |||||

| Ascaris lumbricoides | Roundworm | 1000 to 1450

807 to 1,121[75] |

20,000 | Many regions of South-east Asia, Africa, and Central and South America[76][77][78][79][80][81] | |

| Trichuris trichiura | Whipworm | 500

604–795[75] |

In moist, warm, tropical regions of Asia, Africa, Central and South America, and the Caribbean islands.[78][79][80][81][82] | ||

| Ancylostoma duodenale | Hookworm | 900 to 1300

576–740 (hookworm in general)[83] |

In tropical and subtropical countries (Sub-Saharan Africa)[79][82] | ||

| Necator americanus | |||||

| Strongyloides stercoralis | Hookworm, pinworm | 50 to 100 | Thousands | In moist rainy areas of the tropics and subtropics, in some areas of southern and eastern Europe and of the United States of America[79][80] | |

| All STH together | 1500 to 2000[6] | 135,000[3][69][70] | Tropical and subtropical areas, in particular sub-Saharan Africa, the Americas, China and east Asia.[6] | ||

| Not transmitted via soil but classified as neglected tropical disease: | |||||

| Schistosoma mansoni | Blood fluke | All types of Schistosoma together: 160 to 200

(210 "affected"[84]) |

12,000[85] 150,000 deaths from kidney failure[86]

200,000 indirect deaths from "causes related to" Schistosomiasis[72] |

In tropical and subtropical regions[78][79][80][81][82] | |

| Schistosoma haematobium | 112 (in Sub-Saharan Africa alone)[86] | ||||

| Echinococcus granulosus | 3[87] | Developing countries | |||

| Not transmitted via soil and not classified as neglected tropical disease: | |||||

| Toxocara canis | Dog roundworm | 50 | Many regions of South-east Asia, Africa, and Central and South America[76][77][78][79][80][81] | ||

| Taenia solium | Pork tapeworm | 50 | South America, Southeast Asia, West Africa and East Africa[78][79][80][81] | ||

| Taenia saginata | Beef tapeworm | 50

(all types of Taenia: 40 to 60[88]) |

|||

| Hymenolepis nana | Dwarf tapeworm | 100 | |||

| Hymenolepis diminuta | Rat tapeworm | ||||

| Fasciola hepatica, Fascioloides magna |

Liver fluke | 50 | Largely in southern and eastern Asia but also in central and eastern Europe[79][80] | ||

| Fasciolopsis buski | Giant intestinal fluke | ||||

| Dracunculus medinensis | Guinea worm | Nowadays negligible thanks to eradication program[89] | Formerly widespread in India, west Africa and southern Sudan[79][80] | ||

| Trichostrongylus orientalis | Roundworm | 1–3 ("several") | Rural communities in Asia[79][80] | ||

| Other | 100 | Worldwide[79][80] | |||

| Total (number of infections) | Approx. 3.5 billion | Worldwide | |||

See also

References

- "Neglected Tropical Diseases". cdc.gov. 6 June 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- London Declaration (30 January 2012). "London Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases" (PDF). Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- Report of a WHO Expert Committee (1987). Prevention and Control of Intestinal Parasitic Infections. World Health Organization, Technical Report Series 749.

- Del Rosso, Joy Miller and Tonia Marek (1996). Class Action: Improving School Performance in the Developing World through Better Health and Nutrition. The World Bank, Directions in Development.

- WHO (2012). "Research priorities for helminth infections". World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 972 (972): 1–174. PMID 23420950.

- "Soil-transmitted helminth infections". Fact sheet N°366. May 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Del Brutto OH (2012). "Neurocysticercosis: a review". The Scientific World Journal. 2012: 1–8. doi:10.1100/2012/159821. PMC 3261519. PMID 22312322.

- Madiba T. E.; Hadley G. P. (February 1996). "Surgical management of worm volvulus". South African Journal of Surgery. 34 (1): 33–5, discussion 35–6. PMID 8629187. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Minciullo P. L.; Cascio A.; David A.; Pernice L. M.; Calapai G.; Gangemi S. (2012). "Anaphylaxis caused by helminths: review of the literature". European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 16 (11): 1513–1518. PMID 23111963.

- John, David T.; William A. Petri Jr. (2006). Markell and Vogue's Medical Parasitology, 9th Edition. Saunders Elsevier Press. ISBN 0721647936.

- van Riet E.; Hartgers F. C.; Yazdanbakhsh M. (2007). "Chronic helminth infections induce immunomodulation: consequences and mechanisms". Immunobiology. 212 (6): 475–9. doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2007.03.009. PMID 17544832.

- Mkhize-Kwitshana Z. L.; Mabaso M. H. (2012). "Status of medical parasitology in South Africa: new challenges and missed opportunities". Trends in Parasitology. 28 (6): 217–219. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2012.03.005. PMID 22525798.

- Borkow G.; Bentwich Z. (2000). "Eradication of helminthic infections may be essential for successful vaccination against HIV and tuberculosis". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 78 (11): 1368–9. doi:10.1590/S0042-96862000001100013 (inactive 2021-01-20). PMC 2560630. PMID 11143198.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Alexander J. Lankowski; Alexander C. Tsai; Michael Kanyesigye; Mwebesa Bwana; Jessica E. Haberer; Megan Wenger; Jeffrey N. Martin; David R. Bangsberg; Peter W. Hunt; Mark J. Siedner (7 August 2014). "Empiric Deworming and CD4 Count Recovery in HIV-Infected Ugandans Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (8): e3036. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003036. PMC 4125278. PMID 25101890.

- Means J.R.; Burns P.; Sinclair D. (2016). Means (ed.). "Antihelminthics in helminth-endemic areas: effects on HIV disease progression". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD006419. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006419.pub4. PMC 4963621. PMID 27075622.

- Baron S (1996). "87 (Helminths: Pathogenesis and Defenses by Wakelin D". Medical Microbiology (4 ed.). Galveston (TX): The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0963117212. PMID 21413312.

- Levinger B (1992). Nutrition, Health, and Learning: Current Issues and Trends. School Nutrition and Health Network Monograph Series, #1. Please note that this estimate is less current than the Watkins and Pollitt estimate, leading Levinger to underestimate the number infected.

- The World Bank. "World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health" (PDF).

- Watkins W. E.; Pollitt E. (1997). "'Stupidity or Worms': Do Intestinal Worms Impair Mental Performance?". Psychological Bulletin. 121 (2): 171–91. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.121.2.171. PMID 9100486.

- Crompton, D. W. T. (1993). Human Nutrition and Parasitic Infection. Cambridge University Press.

- Stoltzfus, Rebecca J., et al. (2003). "Low Dose Daily Iron Supplementation Improves Iron Status and Appetite but Not Anemia, whereas Quarterly Antihelminthic Treatment Improves Growth, Appetite, and Anemia in Zanzibari Preschool Children". The Journal of Nutrition. 134 (2): 348–56. doi:10.1093/jn/134.2.348. PMID 14747671.

- Boivin, M. J.; Giordiani B. (1993). "Improvements in Cognitive Performance for Schoolchildren in Zaire, Africa, Following an Iron Supplement and Treatment for Intestinal Parasites". Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 18 (2): 249–264. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/18.2.249. PMID 8492277. 2.

- Nokes, C.; et al. (1992). "Parasitic Helminth Infection and Cognitive Function in School Children". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 247 (1319): 77–81. Bibcode:1992RSPSB.247...77N. doi:10.1098/rspb.1992.0011. PMID 1349184. S2CID 22199934.

- Ezeamama, Amara E., et al. (2005). "Helminth infection and cognitive impairment among Filipino children". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 72 (5): 540–548. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2005.72.540. PMC 1382476. PMID 15891127.

- Sakti, Hastaning; et al. (1999). "Evidence for an Association Between Hookworm Infection and Cognitive Function in Indonesian School Children". Tropical Medicine and International Health. 4 (5): 322–334. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00410.x. PMID 10402967. S2CID 16553760.

- Maya, C.; Torner-Morales, F. J.; Lucario, E. S.; Hernández, E.; Jiménez, B. (2012). "Viability of six species of larval and non-larval helminth eggs for different conditions of temperature, pH and dryness". Water Research. 46 (15): 4770–4782. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2012.06.014. PMID 22794801.

- Charity Water, et al. (2009). "Contaminated drinking water". Charity Water. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bisi-Johnson M. A.; Obi C. L.; Ekosse G. E. (2010). "Microbiological and health related perspectives of geophagia: an overview". African Journal of Biotechnology. 9 (36): 5784–91.

- Crompton D. W. T.; Savioli L. (2007). Handbook of Helminthiasis for Public Health. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, US. pp. 1–362. ISBN 9781420004946.

- Krauth S. J.; Coulibaly J. T.; Knopp S.; Traoré M.; N'Goran E. K.; Utzinger J. (2012). "An In-Depth Analysis of a Piece of Shit: Distribution of Schistosoma mansoni and Hookworm Eggs in Human Stool". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (12): e1969. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001969. PMC 3527364. PMID 23285307.

- Lustigman S.; Prichard R. K.; Gazzinelli A.; Grant W. N.; Boatin B. A.; McCarthy J. S.; Basáñez M. G. (2012). "A research agenda for helminth diseases of humans: the problem of helminthiases". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (4): e1582. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001582. PMC 3335854. PMID 22545164.

- Hunt P. W.; Lello J. (2012). "How to make DNA count: DNA-based diagnostic tools in veterinary parasitology". Veterinary Parasitology. 186 (1–2): 101–108. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.11.055. PMID 22169224.

- "Water, Sanitation & Hygiene: Strategy Overview". Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene: Introduction". UNICEF. UNICEF. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Goal 7: Ensure Environmental Sustainability". United Nations Millennium Development Goals website. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- Hales, S.; Ziegelbauer, K.; Speich, B.; et al. (2012). "Effect of Sanitation on Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLOS Medicine. 9 (1): e1001162. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001162. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 3265535. PMID 22291577.

- Strunz, E. C.; Addiss, D. G.; Stocks, M. E.; et al. (2014). "Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLOS Medicine. 11 (3): e1001620. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001620. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 3965411. PMID 24667810.

- Hotez, P. J.; Diemert, D.; Bacon, K. M.; et al. (2013). "The Human Hookworm Vaccine". Vaccine. 31: B227–B232. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.11.034. ISSN 0264-410X. PMC 3988917. PMID 23598487.

- "Anthelmintics". Drugs.com. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- "Overview of Anthelmintics". The Merck Veterinary Manual. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- Pérez del Villar, Luis; Burguillo, Francisco J.; López-Abán, Julio; Muro, Antonio; Keiser, Jennifer (2012). "Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Artemisinin Based Therapies for the Treatment and Prevention of Schistosomiasis". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e45867. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...745867P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045867. PMC 3448694. PMID 23029285.

- WHO (2006). Preventive chemotherapy in human helminthiasis: coordinated use of anthelminthic drugs in control interventions: a manual for health professionals and programme managers (PDF). WHO Press, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. pp. 1–61. ISBN 978-9241547109.

- Prichard R. K.; Basáñez M. G.; Boatin B. A.; McCarthy J. S.; García H. H.; Yang G. J.; Sripa B.; Lustigman S. (2012). "A research agenda for helminth diseases of humans: intervention for control and elimination". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (4): e1549. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001549. PMC 3335868. PMID 22545163.

- Bundy, Donald A. P.; Walson, Judd L.; Watkins, Kristie L. (2013). "Worms, wisdom, and wealth: why deworming can make economic sense". Trends in Parasitology. 29 (3): 142–148. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2012.12.003. PMID 23332661.

- Albonico, Marco; Allen, Henrietta; Chitsulo, Lester; Engels, Dirk; Gabrielli, Albis-Francesco; Savioli, Lorenzo; Brooker, Simon (2008). "Controlling Soil-Transmitted Helminthiasis in Pre-School-Age Children through Preventive Chemotherapy". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2 (3): e126. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000126. PMC 2274864. PMID 18365031.

- Miguel, Edward; Michael Kremer (2004). "Worms: Identifying Impacts on Education and Health in the Presence of Treatment Externalities". Econometrica. 72 (1): 159–217. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.336.7123. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0262.2004.00481.x.

- Evans, David (2015-08-04). "Economist, World Bank". Development Impact blog, World Bank. World Bank. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Hawkes, N. (2013). "Deworming debunked". BMJ. 346 (jan02 1): e8558. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8558. PMID 23284157. S2CID 5568263.

- Taylor-Robinson, David C.; Maayan, Nicola; Donegan, Sarah; Chaplin, Marty; Garner, Paul (11 September 2019). "Public health deworming programmes for soil-transmitted helminths in children living in endemic areas". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD000371. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000371.pub7. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6737502. PMID 31508807.

- Ahuja, Amrita; Baird, Sarah; Hicks, Joan Hamory; Kremer, Michael; Miguel, Edward; Powers, Shawn (2015). "When Should Governments Subsidize Health? The Case of Mass Deworming". The World Bank Economic Review. 29 (suppl 1): S9–S24. doi:10.1093/wber/lhv008.

- Fincham, J., Dhansay, A. (2006). Worms in SA's children - MRC Policy Brief. Nutritional Intervention Research Unit of the South African Medical Research Council, South Africa

- "Fact sheets: neglected tropical diseases". World Health Organization. WHO Media Centre. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- WHO (2013). Schistosomiasis: progress report 2001 - 2011, strategic plan 2012 - 2020. WHO Press, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. pp. 1–270. hdl:10665/78074?mode=full. ISBN 9789241503174.

- "Malaria". Fact sheet N°94. WHO Media Centre. May 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "Foodborne trematode infections". Factsheet N°368. WHO Media Centre. 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "Lymphatic filariasis". Fact sheet N°102. WHO Media centre. May 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "A global brief on vector-borne diseases" (PDF). World Health Organization. March 2014. p. 22. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- "Echinococcosis". Fact sheet N°377. WHO Media Centre. May 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Ojha, Suvash Chandra; Jaide, Chayannan; Jinawath, Natini; Rotjanapan, Porpon; Baral, Pankaj (2014). "Geohelminths: public health significance". The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 8 (1): 5–16. doi:10.3855/jidc.3183. ISSN 1972-2680. PMID 24423707.

- Velleman, Y., Pugh, I. (2013). Under-nutrition and water, sanitation and hygiene - Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) play a fundamental role in improving nutritional outcomes. A successful global effort to tackle under-nutrition must include WASH. WaterAid and Share, UK

- "Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease)". Fact sheet N°359 (Revised). WHO Media Centre. March 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- Montresor; et al. (2002). "Helminth Control in School-Age Children: A Guide for Managers of Control Programs" (PDF). World Health Organization. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bethony, Jeffrey; Brooker, Simon; Albonico, Marco; Geiger, Stefan M.; Loukas, Alex; Diemert, David; Hotez, Peter J. (2006). "Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm". The Lancet. 367 (9521): 1521–1532. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68653-4. PMID 16679166. S2CID 8425278.

- Kucik CJ, Martin GL, Sortor BV (2004). "Common intestinal parasites". Am Fam Physician. 69 (5): 1161–8. PMID 15023017.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Magill, Alan J.; Hill, David R.; Solomon, Tom; Ryan, Edward T. (2013). Hunter's tropical medicine and emerging infectious diseases (9th ed.). New York: Saunders. p. 804. ISBN 978-1-4160-4390-4.

- Magill, Alan (2013). Hunter's tropical medicine and emerging infectious diseases (9th ed.). New York: Saunders. p. 804. ISBN 978-1-4160-4390-4.

- de Silva, N.; Hotez, P. J.; et al. (2014). "The Global Burden of Disease Study 2010: Interpretation and Implications for the Neglected Tropical Diseases". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (7): e2865. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002865. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 4109880. PMID 25058013.

- Vos, T.; Barber, R. M.; et al. (2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". The Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

- Lustigman S.; Prichard R. K.; Gazzinelli A.; Grant W. N.; Boatin B. A.; McCarthy J. S.; Basáñez M. G. (2012). "A research agenda for helminth diseases of humans: the problem of helminthiases". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (4): e1582. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001582. PMC 3335854. PMID 22545164.

- Yap P.; Fürst T.; Müller I.; Kriemler S.; Utzinger J.; Steinmann P. (2012). "Determining soil-transmitted helminth infection status and physical fitness of school-aged children". Journal of Visualized Experiments. 66 (66): e3966. doi:10.3791/3966. PMC 3486755. PMID 22951972.

- Naghavi, M.; Wang, H.; et al. (2015). "Global, regional, and national age–sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". The Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. hdl:11655/15525. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- Thétiot-Laurent, S. A.; Boissier, J.; Robert, A.; Meunier, B. (27 June 2013). "Schistosomiasis Chemotherapy". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 52 (31): 7936–56. doi:10.1002/anie.201208390. PMID 23813602.

- Kheir M. M.; Eltoum I. A.; Saad A. M.; Ali M. M.; Baraka O. Z.; Homeida M. M. (February 1999). "Mortality due to schistosomiasis mansoni: a field study in Sudan". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 60 (2): 307–10. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.307. PMID 10072156.

- "Neglected Tropical Diseases". cdc.gov. 6 June 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "Parasites – Soil-transmitted Helminths (STHs)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 10 January 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- Blanca Jiménez (2006) Irrigation in developing countries using Wastewater, International Review for Environmental Strategies, 6(2): 229–250.

- B. Jiménez (2007) Helminth ova removal from wastewater for agriculture and aquaculture reuse Archived 2015-07-01 at the Wayback Machine. Water Sciences & Technology, 55(1–2): 485–493.

- I. Navarro, B. Jiménez, E. Cifuentes and S. Lucario (2009) Application of helminth ova infection dose curve to estimate the risks associated with biosolid application on soil Archived 2015-03-19 at the Wayback Machine, Journal of Water and Health 31–44.

- Blanca Jiménez, Inés Navarro (2013) Wastewater Use in Agriculture: Public Health Considerations. Encyclopedia of Environmental Management. Ed., Vol. IV, Dr. Sven Erik Jorgensen (Ed.), DOI: 10.1081/E-EEM-120046689 Copyright © 2012 by Taylor & Francis. Group, New York, NY, pp 3,512.

- UN (2003) Water for People Water for Life. The United Nations World Water Development Report, UNESCOEd, Barcelona, Spain.

- WHO (1995) WHO Model Prescribing Information: Drug Use in Parasitic Diseases. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- WHO (2006). WHO Guidelines for the Safe Use of Wastewater, Excreta and Greywater – Volume IV: Excreta and greywater use in agriculture. World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva, Switzerland

- "Parasites – Hookworm". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017-05-02. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- Fenwick, A (Mar 2012). "The global burden of neglected tropical diseases". Public Health. 126 (3): 233–6. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2011.11.015. PMID 22325616.

- Lozano, R.; Naghavi, M.; Foreman, K.; Lim, S.; Shibuya, K.; Aboyans, V.; Abraham, J.; Adair, T.; et al. (15 December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253.

- Luke F. Pennington and Michael H. Hsieh (2014) Immune Response to Parasitic Infections, Bentham e books, Vol 2, pp. 93–124, ISBN 978-1-60805-148-9

- Elisabetta Profumo, Alessandra Ludovisi, Brigitta Buttari, Maria, Angeles Gomez Morales and Rachele Riganò (2014) Immune Response to Parasitic Infections, Bentham e books, Bentham Science Publishers, Vol 2, pp. 69–91, ISBN 978-1-60805-148-9

- Eckert, J. (2005). "Helminths". In Kayser, F. H.; Bienz, K. A.; Eckert, J.; Zinkernagel, R. M. (eds.). Medical Microbiology. Stuttgart: Thieme. pp. 560–562. ISBN 9781588902450.

- "Dracunculiasis (guinea-worm disease) Fact sheet N°359 (Revised)". World Health Organization. February 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

External links

| Classification |

|---|