Tropical Storm Vicente (2018)

Tropical Storm Vicente was an unusually small tropical cyclone that made landfall as a tropical depression in the Mexican state of Michoacán on October 23, 2018, causing deadly mudslides. The 21st named storm of the 2018 Pacific hurricane season,[1] Vicente originated from a tropical wave that departed from Africa's western coast on October 6. The wave traveled westward across the Atlantic and entered the Eastern Pacific on October 17. The disturbance became better defined over the next couple of days, forming into a tropical depression early on October 19. Located in an environment favorable for further development, the system organized into Tropical Storm Vicente later that day.

| Tropical Storm (SSHWS/NWS) | |

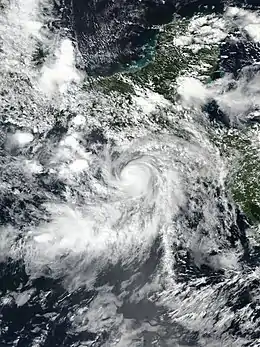

Vicente shortly after reaching tropical storm strength on October 19 | |

| Formed | October 19, 2018 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | October 23, 2018 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 50 mph (85 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 1002 mbar (hPa); 29.59 inHg |

| Fatalities | 16 total |

| Areas affected | Central America, Southwestern Mexico |

| Part of the 2018 Pacific hurricane season | |

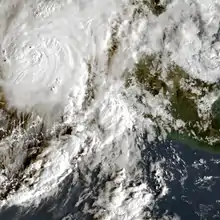

The small cyclone traveled northwestward along the Guatemalan coast before later shifting to a more westerly track. Vicente peaked late on October 20 with winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1,002 mbar (29.59 inHg). At its peak, Vicente displayed a sporadic eye feature in its central dense overcast. The storm maintained this intensity for about eighteen hours as it turned towards the southwest. Dry air caused Vicente to weaken on October 21. A brief break from the dry air during the next day allowed the storm to recuperate and slightly strengthen. However, outflow from the nearby Hurricane Willa caused Vicente to weaken into a tropical depression early on October 23. After making landfall near Playa Azul at 13:30 UTC, Vicente quickly lost organization and dissipated a few hours later.

Vicente caused torrential rainfall in the Mexican states of Michoacán, Oaxaca, Veracruz, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Guerrero, and Colima; the highest total exceeded 12 in (300 mm) in Oaxaca. In some states, the effects of Vicente compounded those from the nearby Hurricane Willa. The storm left a total of 16 people dead throughout 2 states: 13 in Oaxaca and 3 in Veracruz. The heavy rainfall caused numerous rivers to spill their banks, dozens of landslides to occur, and severe flooding to ensue elsewhere. This resulted in hundreds of homes being inundated, dozens of road closures, and agricultural damage amongst an array of other effects. Plan DN-III-E was activated in multiple states to provide aid to affected individuals. The federal and state governments mobilized to help with relief efforts and repairs.

Meteorological history

Tropical Storm Vicente's origins can be traced back to a low-level vortex associated with the eastern Pacific monsoon trough and a tropical wave. The wave departed from Africa's western coast on October 6 and traveled westward across the Atlantic Ocean, arriving at the Lesser Antilles around October 14. Although convection or thunderstorm activity initially flared along the northern side of the wave, it gradually decreased until the wave was completely devoid of convection. The wave came into contact with Central America on October 16; deep convection re-ignited along the monsoon trough and wave south of Panama a day later. Bursts of convection occurred to the south of Nicaragua and El Salvador as the wave proceeded westward into the Eastern Pacific.[2]

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) first mentioned that the system had the potential for tropical development early on October 19. The system was part of a broader disturbance which stretched from Central America to the south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec.[3] Over the next several hours the system rapidly organized, becoming a tropical depression at 06:00 UTC, while located about 90 mi (150 km) west-southwest of Puerto San Jose, Guatemala. The depression's development was not anticipated due to its small size and the close proximity of a larger disturbance to the west (which later become Hurricane Willa).[2] The nascent depression was located in an environment of low wind shear and warm 82–84 °F (28–29 °C) sea surface temperatures, both conducive for further intensification.[4] The structure of the unusually small storm continued to improve, with satellite and microwave imagery showing an increase in banding features around the center. The depression was upgraded into Tropical Storm Vicente around 18:00 UTC. Throughout the majority of October 19, the system was less than 115 mi (185 km) off the coast of Guatemala while it inched towards the northwest.[2]

Early on October 20, increasing northwesterly wind shear disrupted Vicente, causing the degradation of its central dense overcast. At the same time, its low-level center had accelerated towards the northwest and was almost entirely exposed.[5] A deep-layer ridge located over the Gulf of Mexico and central Mexico, as well as a Gulf of Tehuantepec gap wind, caused Vicente's track to shift to the west during the overnight.[2] The tiny tropical cyclone's structure improved over the next several hours, with the storm displaying a sporadic eye feature surrounded by medium to weak convection.[6] Vicente peaked at 18:00 UTC on October 20 with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 1,002 mbar (29.59 inHg). At that time, the storm was located less than 115 mi (185 km) off the coast of Chiapas and Oaxaca, Mexico. Vicente was an unusually small tropical cyclone, with 45–50 mph (70–80 km/h) winds extending only 25 mi (35 km) from its center. The system maintained its peak intensity for approximately 18 hours as it began traveling towards the west-southwest.[2][7]

Dry air began to entrain into the mid-levels of the system on October 21, causing convection to weaken and the low-level center to become uncovered once more.[2][8] The storm turned to the west-northwest early on October 22 as it rounded the southwestern edge of the aforementioned ridge. The structure of Vicente markedly improved while it experienced a brief reprieve from the onslaught of the dry air; a banding feature with cold cloud tops of −112 °F (−80 °C) developed and wrapped around a majority of the storm.[2][9] Later in the day, Vicente began to be affected by the outflow of Hurricane Willa, which was located to the northwest. This outflow imparted northeasterly shear upon Vicente, causing rapid degradation of the system's structure. Banding features decreased significantly and only limited convection remained, displaced to the south and east of Vicente's center.[2][10] Vicente weakened into a tropical depression at 06:00 UTC on October 23 and made landfall near Playa Azul, Michoacán at 13:30 UTC. After moving ashore, Vicente quickly lost its convection and dissipated by 18:00 UTC.[2][11]

Impact

Despite Vicente's close proximity to land, no tropical storm watches or warnings were issued for Guatemala and Mexico.[2] An overall green alert, signifying a low level of danger, was issued for southwestern coast of Mexico.[12] The threats posed by both Vicente and Hurricane Willa forced the Norwegian Bliss cruise ship to divert to San Diego, California.[13] Vicente caused torrential rainfall in multiple states. Peak rainfall of at least 12 in (300 mm) occurred in the state of Oaxaca. Rainfall totals of 6.21 in (157.7 mm) and 5.31 in (134.8 mm) were recorded in Zihuatanejo, Guerrero. In the same state, 4.63 in (117.5 mm) of rain fell in San Jeronimo. Rainfall exceeding 5.9 in (150 mm) registered in Colima state.[14]

Michoacán

Vicente made landfall near Playa Azul, Michoacán at 13:30 UTC (08:30 CDT) on October 23.[2] Schools along the coast of Michoacán were closed to safeguard everyone from the effects of Vicente and Willa.[15] Rainfall from the storm flooded 27 neighborhoods in the city of Morelia.[16] Ventura Puente, Carlos Salazar, Jacarandas, Los Manantiales, and Industrial experienced flooding up to 3.3 ft (1 m) deep, which left hundreds of homes inundated.[17] Residents were evacuated from the Jacarandas neighborhood by state officials and police officers after rainfall caused a gasoline leak to occur.[18] Five schools were closed in the city due to flooding and another for mud removal and disinfection work.[19] The Rio Grande overflowed, and drainage systems were completely filled throughout the Morelia municipality. The heavy rainfall also caused the ground to give way near Atapaneo, resulting in a freight train derailment that left two workers injured.[17][20] Plan DN-III-E, a disaster relief and rescue plan, was activated in the municipality; 500 individuals from the Police Training Institute were dispatched to help those affected by the flooding.[18]

Oaxaca

The system brought heavy rainfall to Oaxaca, causing widespread flooding and mudslides.[21] Torrential rainfall filled four Oaxacan dams to their highest levels in over four years; two of the dams exceeded 90% of their capacity and another exceeded 100%.[22] The floods left 21 communities without any outside communication.[23] Roads in Oaxaca suffered severe damage in 203 sections; machinery was apportioned to clear landslides off roads.[24][25][26] At least 13 people died throughout the state, 6 of whom died in a landslide in San Pedro Ocotepec.[21] A family of four went missing after trying to leave one of the communities.[27][21] Rescue searches for the individuals ceased a week later; they were assumed to have been buried by a landslide.[28] A landslide in Santiago Camotlán buried a house and killed a 40-year-old man. In Tututepec, a 56-year-old man drowned after getting caught in river currents.[29]

Multiple rivers in the state overtopped their banks and inundated nearby communities. A landslide in Santiago Choapam destroyed three homes.[30] A drainage ditch emptying into the Chahué Bay overflowed, flooding at least 80 homes and businesses;[31] a portion of the ditch also collapsed.[32] Rainfall caused a sinkhole to develop on a bridge. A total of five cars were swept away by water currents flowing down streets in Santa Cruz Huatulco.[32] As a result of the flooding, a temporary shelter was enabled in that area.[33] National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples facilities were activated to help 30 people who were affected. The ports of Puerto Ángel, Puerto Escondido, and Huatulco were closed.[31][34] Several communities in the Sierra Norte region were isolated and left without any outside communication by landslides and damaged bridges.[35][36] Crops in that area were destroyed by the storm, leading to food shortages.[37] Vicente damaged schools, health care facilities, houses, and crops in the Sierra Mazateca area.[38] In La Humedad, Mexican Federal Highway 200 was flooded for over 0.62 mi (1 km) and covered by landslides. A fence collapsed and several homes were inundated by floodwaters in Santiago Jamiltepec. Five families were evacuated from their homes in Piedra Ancha due to flooding.[39]

Emergency declarations were issued for 167 municipalities that were severely affected.[40] The Mexican Army and Navy alongside State Police deployed 10,000 personnel to assist in recovery efforts.[23] Plan DN-III-E was activated to disperse aid to the state; a Mexican Air Force helicopter was utilized to get food and supplies to people in affected areas.[41] A disaster declaration was issued for 71 Oaxacan municipalities affected by Vicente; these areas would have access to national disaster relief funds.[42]

Veracruz

Rainfall from the storm triggered flooding in Veracruz, leaving three people dead.[43] A declaration of emergency was issued for 13 municipalities in Veracruz.[44] The town of Tlacotalpan prepared for the overflow of the Papaloapan and Coatzacualcos rivers by creating levees to prevent floodwaters from affecting historical and cultural sites. Multiple landslides were reported on the Zomgolia-Orizaba highway.[45] In the southern portion of the state, the Veracruz-Coatzacoalcos highway was blocked by floodwaters after the Tesochoacán river overflowed.[46] Throughout the state, 21 landslides occurred, and 42 roads and 36 schools sustained damage.[47] In the Álamo-temapache municipality, the Oro Verde stream and the Pantepec river overflowed, flooding multiple streets. Plan DN-III-E was enabled to aid with relief in the state.[29][48]

The San Juan river spilled its banks, completely blocking the Tinaja-Cosoleacaque highway, a road that connects other states to Veracruz. Federal Police stopped cars from crossing a section of the Cosamaloapan-Acayucan highway after the same river left 5.0 mi (8 km) of the road completely submerged under water. Additionally, 1,764 people were evacuated, 15 temporary shelters were activated, and 8 people were rescued throughout the state.[49] Several communities were inundated in Hidalgotitlán after the Coatzacoalcos river overflowed; 790 homes were flooded in the towns of Ramos Millán and Vicente Guerrero. Shelters were setup for affected families and 500 pantries distributed water. Classes in the area were canceled as a result of the floods.[50] Twenty-one emergency declarations were authorized for municipalities in the state.[47][48]

Elsewhere

A total of ten landslides occurred in the state of Hidalgo as a result of heavy rainfall from Vicente and the nearby Willa. In the municipalities of Huasteca and Sierra, highway accesses were blocked by boulders and tree limbs. Two people were hospitalized due to a landslide in Zacualtipán. Seven people were evacuated after a house was buried in Calnali.[51] Roads in Huehuetla and Tenango del Valle were impassable due to landslides. Landslides affected the Tlanchinol-Hueyapa state highway in Tepehuacán de Guerrero, the Pachuca-Huejutla highway in the Mineral del Chico municipality, and on the Mexico-Tampico federal highway.[52] The rains also filled several dams and reservoirs in the state to over 90% of their capacity, however, there was no risk of failure as a result of active spillways.[53]

Due to the unsettled weather produced by Vicente and the nearby Willa, numerous oil tankers were unable to unload fuel at ports in Manzanillo and Tuxpan. Combined with the closure of a major pipeline that transports petroleum to Guadalajara, this caused a fuel shortage in Jalisco, with some 500 gas stations being affected.[54] Damage to gasoline distribution centers in Manzanillo and Tuxpan as well as a refinery in Salamanca led to shortages in Jalisco, Nayarit, and Colima.[55] Heavy rainfall from Vicente and Willa caused a total of 24 landslides on highways in Jalisco, with about half occurring on El Tuito-Melaque-Cabo Corrientes section of Mexican Federal Highway 200.[56] Agricultural losses in the state of Colima from Vicente and Willa were estimated to be about MX$136 million (US$7.05 million).[57]

The state of Guerrero also experienced the effects of Vicente. One home flooded in Tixtla de Guerrero and another in Tecpan; the latter's roof also collapsed. Mudslides were reported on two roads in the state. The state government activated over 500 shelters with enough capacity to house 100,000 people. The Tesechoacán, Papaloapan, and San Juan rivers began to overflow from heavy rainfall.[58] The storm felled 16 trees in Zihuatanejo; sewers were congested with garbage, leading to street flooding in multiple places throughout the city.[59]

See also

- Other storms of the same name

- Hurricane Carlos (2015) – Another unusually small tropical cyclone that took a similar path[60]

- Tropical Storm Odile (2008) – Another October tropical storm with a similar path and intensity[61]

References

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center. "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2019". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved 1 October 2020. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- Latto, Andrew; Beven, John (10 April 2019). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Vicente (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Zelinsky, David (19 October 2018). Tropical Weather Outlook [23:55 UTC, Thu Oct 18, 2018] (Report). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Berg, Robbie (19 October 2018). Tropical Depression Twenty-Three-E Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Zelinsky, David (20 October 2018). Tropical Storm Vicente Discussion Number 3 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Avila, Lixion (20 October 2018). Tropical Storm Vicente Discussion Number 6 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Stewart, Stacy (21 October 2018). Tropical Storm Vicente Discussion Number 8 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Pasch, Richard (21 October 2018). Tropical Storm Vicente Discussion Number 10 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Roberts, Dave (22 October 2018). Tropical Storm Vicente Discussion Number 12 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Pasch, Richard (22 October 2018). Tropical Storm Vicente Discussion Number 14 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Pasch, Richard (23 October 2018). Post-Tropical Cyclone Vicente Discussion Number 17 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Overall Green alert Tropical Cyclone for VICENTE-18 (Report). Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System. 19 October 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Saunders, Mark. "Tropical storms force Norwegian Bliss cruise ship to divert to San Diego". KGTV San Diego. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- "Precipitación acumulada (mm) del 20 al 23 de octubre de 2018 por el tormenta tropical Vicente" (Map). gob.mx (in Spanish). Conagua. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Bustos, Juan (23 October 2018). "Willa y Vicente ponen en alerta a la costa; suspenden clases (infografía)". La Voz de Michoacan (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Tinoco, Miguel García (22 October 2018). "Inundan intensas lluvias 30 colonias de Morelia, Michoacán". Excélsior (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "La tormenta tropical Vicente causa inundaciones en Morelia, Michoacán". PSN En Linea (in Spanish). 22 October 2018. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Activan Plan DN-III por lluvia e inundación en Morelia, Michoacán" (in Spanish). Noticieros Televisa. 22 October 2018. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Piña, Ireri (25 October 2018). "Por lo menos 5 escuelas de Morelia siguen inundadas". Contramural.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- "Galeria: "Vicente" y "Willa" dejan inundaciones, desastre y muerte". La Silla Rota (in Spanish). 22 October 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Olivera, Alondra (22 October 2018). "Tormenta Tropical "Vicente" deja 12 víctimas en Oaxaca". La Silla Rota (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Luciana, Citlalli (24 October 2018). "Presas de Oaxaca rebasan el 90% de su almacenamiento". NVI Noticias (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Tormenta "Vicente" deja Comunidades Incomunicadas en Oaxaca" (in Spanish). Noticieros Televisa. 23 October 2018. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Government of Oaxaca (27 October 2018). "Atienden carreteras afectadas por la tormenta tropical Vicente". Quadratin (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Torres, Humberto (27 October 2018). "Decenas de derrumbes impiden comunicación en comunidades de Oaxaca". El Imparcial de Oaxaca (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Hernandez, Carlos Alberto (28 October 2018). "Trabaja SCT en 6 tramos carreteros y 30 caminos rurales de Oaxaca". El Imparcial de Oaxaca (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 September 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- García, Ismael (23 October 2018). "Gobernio de Oaxaca busca a 4 personas desaparecidas tras "Vicente"". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Olivera, Alondra (1 November 2018). "Luto en Metaltepec, Oaxaca concluye búsqueda de familia sepultada por lodo". La Silla Rota (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 1 November 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Ejército rescata a familias atrapadas por inundaciones en Álamo, Veracruz". La Razón de México. 22 October 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- García, Ismael (21 October 2018). "Suman 9 muertos per tormenta tropical "Vicente" en Oaxaca". El Universal (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- "Tormenta tropical 'Willa' se forma frente a Colima; 'Vicente' inunda casas en Oaxaca". Ejecentral (in Spanish). 20 October 2018. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Laguna, Raul (21 October 2018). "Tormenta tropical golpea Huatulco y Pochutla en Oaxaca". El Imparcial de Oaxaca (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Implementan operativo de apoyo a afectados por tormenta Vicente" (in Spanish). UnoTV. 20 October 2018. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Cierran Puerto Escondido a la navegación por tormenta tropical Vicente (+video)" (in Spanish). 24-Horas Mexico. 19 October 2018. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Cruz, Sayra (22 October 2018). "Reportan daños en 119 tramos carreteros en Oaxaca". El Imparcial de Oaxaca (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Incomunicados y abandonados en Yetzelalag, Oaxaca". NVI Noticias. 6 December 2018. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Luciana, Citlalli (10 November 2018). "Sigue emergencia en la Sierra Juárez de Oaxaca". NVI Noticias (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Pineda, Andrés Carrera (30 October 2018). "Dana tormenta Vicente red carretera de la Canada de Oaxaca". El Imparcial de Oaxaca (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Jimenez, Elfego (21 October 2018). "Costa Chica de Oaxaca afectada por la Iluvia". El Imparcial de Oaxaca (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Por daños de "Vicente", Oaxaca solicita Declaratoria de Emergencia para 167 municipios". ADN Suerste (in Spanish). 22 October 2018. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Hernandez, Carlos Alberto (4 November 2018). "Permanecen daños en 27 tramos carreteros de la Sierra Juárez de Oaxaca". El Imparcial de Oaxaca (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 20 November 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Declara Segob desastre en 71 municipios de Oaxaca" (in Spanish). 24-Horas Mexico. 6 November 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Zamudio, Isabel (22 October 2018). "Tormenta tropical 'Vicente' deja tres muertos en Veracruz". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "Emergencia en Oaxaca y Veracruz por tormenta tropical Vicente". ADN40 (in Spanish). 20 October 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "ALERTA: "Willa" y "Vicente" provocan graves daños en México". La Verdad Noticias (in Spanish). 24 October 2018. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Ríos Papaloapan y Coatzacoalcos podrían desbordar por lluvias provocadas por 'Vicente'" (in Spanish). Noticieros Televisa. 24 October 2018. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Lluvias afectan 52 municipios en Veracruz". Posta (in Spanish). 22 October 2018. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Lluvias dejan inundaciones en 21 municipios de Veracruz; en Oaxaca, 9 localidades están incomunicadas". Sinembargo.mx (in Spanish). 21 October 2018. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Alor, José Manuel (23 October 2018). "Vicente desborda río y afecta autopista en Veracruz" (in Spanish). UnoTV. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Desbordamiento de río afecta 790 viviendas en Hidalgotitlán, Veracruz" (in Spanish). Noticieros Televisa. 20 October 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Deja lluvia vías con bloqueos y dos lesionados en Hidalgo". Criterio Hidalgo (in Spanish). 23 October 2018. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Van 10 desgajamientos por lluvias en Hidalgo; afectan carreteras y vialidades". El Heraldo de México (in Spanish). 23 October 2018. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Ocádiz, Concepción (25 October 2018). "Elevados niveles en presas de Hidalgo no representan riesgos". El Sol de Hidalgo. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Jalisco fuel shortages due to hurricane, tropical storm, pipeline taps". Mexico News Daily. November 6, 2018. Archived from the original on December 4, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- Escamilla, Héctor (1 November 2018). "Padece Jalisco, Colima y Nayarit desabasto de gasolina". Publimetro (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ""Willa" y "Vicente" provocan derrumbes en carreteras federales de Jalisco". El Universal (in Spanish). 23 October 2018. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Munguía, Bertha (24 October 2018). "Daños mínimos deja "Willa" y " Vicente"". Meganoticias (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 November 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- "Lluvias provocan daños en viviendas y derrumbes carreteros en Guerrero" (in Spanish). Noticieros Televisa. 21 October 2018. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Las afectaciones que dejó Vicente en Zihuatanejo" (in Spanish). UnoTV. 24 October 2018. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Beven, John; Landsea, Christopher (27 October 2015). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Carlos (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- Beven, John (19 November 2008). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Odile (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tropical Storm Vicente (2018). |

- The National Hurricane Center's advisory archive on Tropical Storm Vicente