Celesta

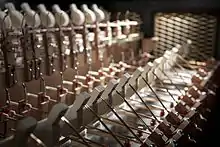

The celesta /sɪˈlɛstə/ or celeste /sɪˈlɛst/, also called a bell-piano, is a struck idiophone operated by a keyboard. It looks similar to an upright piano (four- or five-octave), albeit with smaller keys and a much smaller cabinet, or a large wooden music box (three-octave). The keys connect to hammers that strike a graduated set of metal (usually steel) plates or bars suspended over wooden resonators. Four- or five-octave models usually have a damper pedal that sustains or damps the sound. The three-octave instruments do not have a pedal because of their small "table-top" design. One of the best-known works that uses the celesta is Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" from The Nutcracker.

| |

| Keyboard instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Celeste |

| Classification | Idiophone |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 111.222 (Sets of percussion plaques) |

| Inventor(s) |

|

| Developed |

|

| Playing range | |

| C4 - C8 | |

| Related instruments | |

The sound of the celesta is similar to that of the glockenspiel, but with a much softer and more subtle timbre. This quality gave the instrument its name, celeste, meaning "heavenly" in French. The celesta is often used to enhance a melody line played by another instrument or section. The delicate, bell-like sound is not loud enough to be used in full ensemble sections; as well, the celesta is rarely given standalone solos.

The celesta is a transposing instrument; it sounds one octave higher than the written pitch. Its four-octave sounding range is generally considered to be C4 to C8. The fundamental frequency of 4186 Hz makes this one of the highest pitches in common use. The original French instrument had a five-octave range, but because the lowest octave was considered somewhat unsatisfactory, it was omitted from later models. The standard French four-octave instrument is now gradually being replaced in symphony orchestras by a larger, five-octave German model. Although it is a member of the percussion family, in orchestral terms it is more properly considered a member of the keyboard section and usually played by a keyboardist. The celesta part is normally written on two braced staves, called a grand staff.

History

The celesta was invented in 1886 by the Parisian harmonium builder Auguste Mustel. His father, Charles Victor Mustel, had developed the forerunner of the celesta, the typophone, in 1860. This instrument produced sound by striking tuning forks instead of the metal plates that would be used in the celesta. The dulcitone functioned identically to the typophone and was developed concurrently in Scotland; it is unclear whether their creators were aware of one another's instrument.[1] The typophone/dulcitone's uses were limited by its low volume, too quiet to be heard in a full orchestra.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky is usually cited as the first major composer to use this instrument in a work for full symphony orchestra. He first used it in his symphonic poem The Voyevoda, Op. posth. 78, premiered in November 1891.[2] The following year, he used the celesta in passages in his ballet The Nutcracker (Op. 71, 1892), most notably in the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy, which also appears in the derived Nutcracker Suite, Op. 71a. However, Ernest Chausson preceded Tchaikovsky by employing the celesta in December 1888 in his incidental music, written for a small orchestra, for La tempête (a French translation by Maurice Bouchor of William Shakespeare's The Tempest).[3]

The celesta is also notably used in Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 6, particularly in the 1st, 2nd and 4th movements, in his Symphony No. 8 and Das Lied von der Erde. Karol Szymanowski featured it in his Symphony No. 3. Gustav Holst employed the instrument in his 1918 orchestral work The Planets, particularly in the final movement, Neptune, the Mystic. It also features prominently in Béla Bartók's 1936 Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta. George Gershwin included a celesta solo in the score to An American in Paris. Ferde Grofe also wrote an extended cadenza for the instrument in the third movement of his Grand Canyon Suite. Dmitri Shostakovich included parts for celesta in seven out of his fifteen symphonies, with a notable use in the fourth symphony's coda.

Twentieth-century American composer Morton Feldman used the celesta in many of his large-scale chamber pieces such as Crippled Symmetry and For Philip Guston, and it figured in much of his orchestral music and other pieces. In some works, such as "Five Pianos" one of the players doubles on celesta.

The celesta is used in some 20th-century opera scores including the Silver Rose scene in Der Rosenkavalier (1911)[4] and Carl Orff's Carmina Burana (1936).[5]

The keyboard glockenspiel part in Mozart's The Magic Flute is nowadays often played by a celesta.[6]

Use in other musical genres

Jazz

Since Earl Hines took it up in 1928, other jazz pianists have occasionally used the celesta as an alternative instrument. In the 1930s, Fats Waller sometimes played celesta with his right hand and piano simultaneously with his left hand. Other notable jazz pianists who occasionally played the celesta include Memphis Slim, Meade "Lux" Lewis, Willie "The Lion" Smith, Art Tatum, Duke Ellington, Thelonious Monk, Buddy Greco, Oscar Peterson, McCoy Tyner, Sun Ra, Keith Jarrett, and Herbie Hancock. A celesta provides the introduction to Someday You'll Be Sorry, a song Louis Armstrong recorded for RCA, and is featured prominently throughout the piece. A number of recordings Frank Sinatra made for Columbia in the 1940s feature the instrument (for instance I'll Never Smile Again),[7] as do many of his albums recorded for Capitol in the 1950s (In the Wee Small Hours, Close to You and Songs for Swingin' Lovers).[8]

Rock and pop

Notable pop and rock songs recorded with the celesta include:

- "Jethro Tull – The String Quartets" by Jethro Tull -

- "Rhythm of the Rain" by The Cascades

- "Everyday" by Buddy Holly[9]

- "Baby It's You" as recorded by The Beatles[10]

- "Girl Don't Tell Me" by The Beach Boys

- "Cherish" by The Association

- "She's a Rainbow" by The Rolling Stones

- "Sunday Morning" and "Stephanie Says" by The Velvet Underground[11]

- "Wee Baby Blues" by Climax Blues Band

- "Northern Sky" by Nick Drake

- "Maggie May" and "Mine for Me" by Rod Stewart

- "New York City" by Owl City

- "Penetration" by The Stooges[12]

- "Novocaine for the Soul", "Flyswatter", "Trouble with Dreams" and many other songs by Eels

- "Every Single Night" by Fiona Apple

- "Tarkus" by Emerson, Lake & Palmer

- "Here Today" by Illinois Speed Press

- "Love is a Beautiful Thing" by Vulfpeck

- "Queen of Them All" by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young

Before the instrument was converted, Icelandic band Sigur Rós borrowed it for their album Takk....[13] The lead singer Jónsi used a celesta in Go Quiet, the acoustic version of his solo album Go. Steven Wilson uses the celesta on various tracks in his solo works.

The Italian 1970s progressive rock band Celeste was named after the instrument.

Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band used a celesta heavily in their early days, with Danny Federici often playing a Jenco Celestette in the band's live performances throughout the 1970s and 80s.

Sheryl Crow plays celesta on her 2017 album, Be Myself.[14]

Soundtrack

The celesta has been common in cinema for decades. In addition to supplementing numerous soundtrack orchestrations for films of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, the celesta has occasionally been spotlighted to invoke a whimsical air. For example, in Pinocchio (1940), a small motif on the celesta is used whenever the Blue Fairy appears out of thin air or performs magic. Celesta also provides the signature opening of Pure Imagination, a song (sung by Gene Wilder) from the 1971 film Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory. Composer John Williams's scores for the first three Harry Potter films feature the instrument, particularly in the first two films' frequent statements of "Hedwig's Theme".

Another notable use of the celesta was in the music on the children's television series Mister Rogers' Neighborhood. It was most famously heard in the intro to the theme song of the programme, "Won't You Be My Neighbor", which began with a dreamy sequence on the instrument. The song was sung by Fred Rogers and played by Johnny Costa. It was also used from time to time in other music sequences throughout the programme, such as the one heard as the Neighborhood Trolley moved in and out of the Neighborhood of Make Believe.

A celesta is used in the full orchestral version of the theme song from the TV series The West Wing, composed by W. G. Snuffy Walden.[15]

Manufacturers

Schiedmayer[16] and Yamaha[17] are the only companies currently making celestas. Other known manufacturers that made celestas in the past include:

- Mustel & Company (Paris, France)

- Simone Bros. Celeste MFGS (Philadelphia and New York, US)

- Morley (England)

- Jenco (Decatur, Illinois, US)

- Helmes (New York, US)

Substitutes

If an ensemble or orchestra lacks a celesta, a piano, synthesizer, or sampler and electronic keyboards are often used as a substitute.

See also

- Electric piano

- Voix céleste on organs

Notes

- Mo, Sue. "Dulcitone". Sumo55 Websites & Multi Media Design. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- Freed, Richard. [LP Jacket notes.] "Tchaikovsky: 'Fatum,' ... 'The Storm,' ... 'The Voyevoda.'" Bochum Orchestra. Othmar Maga, conductor. Vox Stereo STPL 513.460. New York: Vox Productions, 1975.

- Blades, James and Holland, James. "Celesta"; Gallois, Jean. "Chausson, Ernest: Works", Grove Music Online (Accessed 8 April 2006) (subscription required)

- Luttrell, Guy L. (1979). The Instruments of Music, p.165. Taylor & Francis.

- "Juan Vicente Mas Quiles – Carmina Burana, published by Schott Music

- "An Overview of Yamaha Celestas" retrieved 13 March 2012

- "All Or Nothing At All: A Life of Frank Sinatra", DonaldClarkeMusicBox.com.

- "500 Greatest Albums of All Time, 100/500: In the Wee Small Hours – Frank Sinatra Archived 2012-05-27 at the Wayback Machine", RollingStone.com.

- "Everyday by Buddy Holly", SongFacts.com.

- "'Baby It's You' History", BeatlesBooks.com.

- "Lou Reed—Sunday Morning", CreemMagazine.com.

- (August 27, 2010). "Iggy Pop keeps Stooges raw, real", ChicagoTribune.com.

- "Takk... documentary", sigur-ros.co.uk.

- Be Myself at Discogs

- 2017. Armando Stettner, personal correspondence with composer.

- "Schiedmayer Celesta". Schiedmayer GmbH. Retrieved 2016-01-03. Schiedmayer's website claims that it "... is today the only Celesta manufacturer worldwide": Schiedmayer is the only company manufacturing celestas according to the patent of A. Mustel and claims the instruments build by Yamaha are "keyboard glockenspiels". However, this claim is contradicted by Yamaha.

- "An Overview of Yamaha Celestas". Yamaha Corporation. Retrieved 2016-01-03. Yamaha's website states that it has manufactured Celestas since 1992.

References

- "Celesta", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London, 2001).

- "Celesta", The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, second edition, edited by Barry Kernfeld (London, 2002).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Celestas. |

- "The Celesta: The Sound of the Sugar Plum Fairy", by Miles Hoffman. Listen on npr.org.

- "Songs for Celesta", by Marc Sanchez