Turkish Van

The Turkish Van is a semi-long-haired breed of domestic cat, which was developed in Turkey from a selection of cats obtained from various cities of modern Turkey, especially Southeast Turkey.[1]:112 The breed is rare,[2] and is distinguished by the Van pattern (named for the breed), where the colour is restricted to the head and the tail, and the rest of the cat is white;[2] this is due to the expression of the piebald white spotting gene, a type of partial leucism.[3]:148 A Turkish Van may have blue or amber eyes, or be odd-eyed (having one eye of each colour). The breed has been claimed to be descended from the landrace of usually all-white Van cats (Turkish: Van kedisi), mostly found near Lake Van,[2] though one of the two original breeders' own writings indicate clearly that none of the breed's foundation cats came from the Van area.[1]:114[4]

| Turkish Van | |

|---|---|

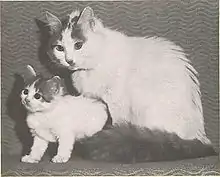

A Turkish Van | |

| Other names | Turkish Cat (obsolete) |

| Origin | Turkey (foundation stock), (initial breeding programme) |

| Breed standards | |

| CFA | standard |

| FIFe | standard |

| TICA | standard |

| AACE | standard |

| ACF | standard |

| ACFA/CAA | standard |

| GCCF | standard |

| Domestic cat (Felis catus) | |

Then called the Turkish Cat, the breed was first recognised as such by a breeder/fancier organisation, the UK-based Governing Council of the Cat Fancy (GCCF), in 1969.[1]:113 It was later renamed "Turkish Van" to better distinguish it from the Turkish Angora breed. The term "Turkish Vankedisi" is used by some organisations as a name for all-white specimens of the formal Turkish Van breed,[5] nomenclature easily confused with the Van kedisi landrace cats, which are also often all-white.

Breed standards

Breed standards allow for one or more body spots as long as there is no more than 20% colour and the cat does not give the appearance of a bicolour. A few random spots are acceptable, but they should not detract from the pattern. The rest of the cat is white. Although red tabby and white is the classic van colour, the colour on a Van's head and tail can be one of the following: red, cream, black, blue, red tabby, cream tabby, brown tabby, blue tabby, tortoiseshell, dilute tortoiseshell (also known as blue-cream), brown-patched tabby, blue-patched tabby, and any other colour not showing evidence of crossbreeding with the point-coloured breeds (Siamese, Himalayan, etc.). Not all registries recognise all of these colour variations.

While a few registries recognise all-white specimens as Turkish Vans, most do not. The US-based Cat Fanciers' Association (CFA, the world's largest registry of pedigreed cats) and Fédération Internationale Féline (FIFe, the largest international cat fancier organisation) recognise only van-patterned specimens, as they define the breed by both its type and pattern. The Germany-based but international World Cat Federation (WCF) considers the all-white specimens a separate breed, which it calls the Turkish Vankedisi,[5] a name that is easily confused with the landrace Van kedisi (Van cat).

Varieties

Black

Black Red

Red Red tabby

Red tabby Tortoiseshell

Tortoiseshell

Origins

In 1955, two British women, Laura Lushington and Sonia Halliday, were given some cats that featured what is now termed the Van pattern on a trip to Turkey, and decided to bring them home. They bred true, and were used as foundation stock for the breed. According to Lushington, her original imported cats were: Van Iskenderun Guzelli (female), a cat that came from Hatay Province, Iskenderun, and Stambul Byzantium (male), a cat given by a hotel manager in Istanbul, both in 1955. Two later additions to the gene pool were Antalya Anatolia (female), from the city of Antalya, and Burdur (male), from Burdur city, both in 1959. Lushington did not see Van city before 1963, and only stayed there "for two days and two nights".[4] It is unclear why the name "Turkish Van" was chosen, or why one of the original 1955 kittens was named "Van Iskenderun Guzelli", given their provenance. Of the founding 1955 pair, Lushington wrote, in 1977:

I was first given a pair of Van kittens in 1955 while traveling in Turkey, and decided to bring them back to England, although touring by car and mainly camping at the time – the fact that they survived in good condition showed up the great adaptability and intelligence of their breed in trying circumstances. Experience showed that they bred absolutely true. They were not known in Britain at that time and, because they make such intelligent and charming pets, I decided to try to establish the breed, and to have it recognised officially in Britain by the GCCF.[1]:114

It is unclear whether Lushington was intending to imply that the Hatay and Istanbul kittens had originally come from the Lake Van region, or was simply referring to the Turkish Van founding stock as "Van kittens" for short. Neither city is anywhere near Van Province.

Turkish Vans were first brought to the United States in 1982 and accepted into championship for showing in the Cat Fanciers' Association (CFA) in 1994. Since then, CFA has registered approximately 100 Vans born each year in the US, making them one of the rarest cat breeds. Imported Vans have no human breeding intervention and are quite robust. No other breed is allowed to be mixed into the breeding schedule, and all registered Turkish Vans can trace their ancestry back to imported cats of Laura Lushington.[4]

Called the Turkish cat when first given breed recognition in 1969,[6] the name was changed in 1979 in the UK (1985 in the US) to Turkish Van[2][7] to better distance the breed from the Turkish Angora cat (originally called Angora[1]:35) which had its origins around Ankara, in central Turkey.

Physical characteristics

.jpg.webp)

The coat on a Turkish Van is considered semi-long-haired.[2] While many cats have three distinct hair types in their coat – guard hair, awn hair and down hair – the Turkish Van has no evident undercoat, only one coat.[8] This makes their coat feel like cashmere[2] or rabbit fur. The lack of an undercoat gives a sleek appearance.[2] The coat is uncommonly water repellant,[2] which makes bathing these cats a challenge, though the coat dries quickly.

The Turkish Van is one of the larger cat breeds. Ideal type should feature broad shoulders with a body that is "top-heavy", that is, a cat with its center of gravity forward. The cat is moderately long, and its back legs are slightly longer than its front legs, but neither the cat itself nor its legs are so long as to be disproportionate. These cats are large and muscular. Males can reach 16 pounds (7 kg) and the females weigh about 12 to 14 lb (5 to 6 kg). They have large paws and rippling hard muscle structure which allows them to be very strong jumpers. Vans can easily hit the top of a refrigerator from a cold start on the floor. They are slow to mature and this process can take 3 years, possibly longer. Vans have been known to reach 3 ft (1 m) long from nose to tip of tail.

Behaviour

The Turkish Van is an excellent hunter.[8] Although early bloodlines had a tendency to be aggressive,[2] today the breed is generally very social, with a friendly disposition toward people,[2] and the cats tend to develop a strong bond with their owners. Turkish Vans, not just with their owner, are friendly to other animals. They prefer other cats to be of the same kind, but will accept other kinds of cats. They are also friendly to "cat friendly dogs" as well.[2] They are very playful and lively.[2] Many Turkish Vans will play fetch, and may bring a toy to their owner to initiate play.[2]

The native Van cat landrace of Turkey have been nicknamed the "swimming cats", due to an unusual fascination with water.[4] Despite the modern Turkish Van breed consisting almost entirely of pedigreed, indoor-only cats with no access to large bodies of water, and despite dubious connections between them and the cats of the Lake Van area, some feel that the Turkish Van has a notable affinity for water; for example, instead of swimming in a lake, they may stir their water bowls or play with water in the toilet,[8] and some may even follow their owners into water.[2] However, the idea that the breed likes water more than other cats may be mistaken according to some pet writers.[9]

Genetics

The piebald spotting gene (partial leucism) appears in other different species (like the horse and the ball python). It also shows up in the common house cat, and other breeds of cat, since the van pattern is merely an extreme expression of the gene.[3]:148

A Turkish Van may have blue eyes, amber eyes, or be odd-eyed[2] (having one eye of each colour, a condition known as heterochromia iridis). The variability of eye colour is genetically caused by the white spotting factor, which is a characteristic of this breed. The white spotting factor is the variable expression of the piebald gene that varies from the minimal degree (1), as in the blue-eyed cats with white tip on the tail to the maximal degree (8–9) that results in a Van-patterned cat, as in Van cats, when coloured marks occupy at most 20% of the white background, but the white background in the breed covers about 80% of the body. Breeding two cats together with the same level of white spotting will produce cats with a similar degree of spotting.[3]:148

Van-patterned Turkish Vans are not prone to deafness, because their phenotype is associated with the van pattern (Sv) semi-dominant gene. Solid-white Turkish angoras carry the epistatic (masking) white colour (W) dominant gene associated with white fur, blue eyes and often deafness. All white Van cats may share this gene. All three types of cat may exhibit eye colours that are amber, blue or odd. Deafness is principally associated with cats having two blue eyes.[3]:191

See also

References

- Pond, Grace (ed.) (1972). The Complete Cat Encyclopedia. London: Walter Parrish Intl. ISBN 0-517-50140-6.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) This tertiary source reuses information from other sources but does not name them.

- "Turkish Van Cats". Retrieved 8 April 2014. This tertiary source reuses information from other sources but does not name them. This source, in some places, conflates the Turkish Van breed and the Van cat landrace.

- Vella, Carolyn; Shelton, Lorraine; McGonagle, John; Stanglein, Terry (1999), Robinson's Genetics for Cat Breeders and Veterinarians (4th ed.), Oxford: Butterworth Heineman, p. 253, ISBN 0-7506-4069-3

- Lushington, Laura (1963), "The Swimming Cats", Animals, 1 (17): 24–27, archived from the original on 2 August 2014,

My photographer and I were given special permits visit Van by air, for two days and two nights(...) Now at least I have been to Van, in Eastern Turkey, and seen with my own eyes the ancient city of Van and the glorious Lake Van

- "Recognized and Admitted Breeds in the WCF". WCF-Online.de. Essen, Germany: World Cat Federation. 2009. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- Rex, Abyssinian and Turkish Cats, by Alison Ashford and Grace Pond, ISBN 0-668-03356-8

- Turkish Van Cat Club newsletter, Van Cat Chat No. 5. Winter 1985/1986

- "Turkish Van: Physical Characteristics". PetMD. 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- Hart, Robert (2010). Hart's Original Petpourri. 1. Langdon Street Pr. p. 4. ISBN 9781934938621. Hart cites a Cat Fancy magazine article as his source.

- Raupach, Denise; et al. "The Turkish Van: Ancient Middle Eastern Mountain Cat". TICA Trend (April/May 2007). The International Cat Association – via TurkishVanCat.org. (Conflates the early history of the Turkish Van with the Van cat, but has modern information on the breed in TICA.)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Turkish Van. |