Twelve Tribes of Israel

The Twelve Tribes of Israel (Hebrew: שבטי ישראל, romanized: Shivtei Yisrael, lit. 'Tribes of Israel') are, according to Judeo-Christian texts, the descendants of the Biblical patriarch Jacob, also known as Israel, through his twelve sons by various women, who collectively form the Israelite nation. Within ancient Judaism, one's tribal affiliation had a great impact on their practices and opportunities, as some tribes enjoyed privileges others did not and some tribes received more blessings than others.

| Tribes of Israel |

|---|

|

| The Tribes |

| Related topics |

Biblical narrative

Jacob, later called Israel, was the second-born son of Isaac and Rebecca, the younger twin brother of Esau, and the grandson of Abraham and Sarah. According to Biblical texts, he was chosen by Yahweh to be the patriarch of the Israelite nation. From what is known of Jacob, he had two wives, sisters Leah and Rachel, and two mistresses, sisters Bilhah and Zilpah, by whom he had at least thirteen children. Though it is possible he may have had more sons and daughters than what is recorded in surviving texts, only twelve sons would form the basis for the twelve tribes of Israel: Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, Zebulun, Joseph, Benjamin, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, and Asher. Jacob was known to display favoritism among his children, particularly for Joseph and Benjamin, the sons of his favorite wife, Rachel, and so, the tribes themselves were not treated equally in a divine sense. Joseph, despite being the second-youngest son, received double the inheritance of his brothers, treated as if he were the firstborn son instead of Reuben, and so, his tribe was later split into two tribes, named for his sons, Ephraim and Manasseh.

Sons and tribes

.jpg.webp)

The Israelites were the twelve sons of the biblical patriarch Jacob. Jacob also had one daughter, Dinah, whose descendants were not recognized as a separate tribe. The sons of Jacob were born in Padan-aram from different mothers, as follows:[1]

- The sons of Leah; Reuben (Jacob's firstborn), Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, and Zebulun

- The sons of Rachel; Joseph and Benjamin

- The sons of Bilhah, Rachel's handmaid; Dan and Naphtali

- The sons of Zilpah, Leah's handmaid; Gad and Asher

Deuteronomy 27:12–13 lists the twelve tribes:

- Reuben (Hebrew ראובן Rəʼûḇēn)

- Simeon (שמעון Šimʻôn)

- Levi (לוי Lêwî)

- Judah (יהודה Yehuḏā)

- Issachar (יששכר Yiśśāḵār)

- Zebulun (זבולון Zəḇūlun)

- Dan (דן Dān)

- Naphtali (נפתלי Nap̄tālî)

- Gad (גד Gāḏ)

- Asher (אשר ’Āšêr)

- Benjamin (בנימין Binyāmîn)

- Joseph (יוסף Yôsēp̄), later split into two "half-tribes":

Jacob elevated the descendants of Ephraim and Manasseh (the two sons of Joseph and his Egyptian wife Asenath)[2] to the status of full tribes in their own right due to Joseph receiving a double portion after Reuben lost his birth right because of his transgression with Bilhah.[3]

In the biblical narrative, the period from the conquest of Canaan under the leadership of Joshua until the formation of the United Kingdom of Israel passed with the tribes forming a loose confederation, described in the Book of Judges. Modern scholarship has called into question the beginning, middle, and end of this picture[4][5] and the account of the conquest under Joshua has largely been abandoned.[6][7][8] The Bible's depiction of the 'period of the Judges' is widely considered doubtful.[4][9][10] The extent to which a united Kingdom of Israel ever existed is also a matter of ongoing dispute.[11][12][13]

Living in exile in the sixth century BCE, the prophet Ezekiel has a vision for the restoration of Israel,[14] of a future in which the twelve tribes of Israel are living in their land again.[15]

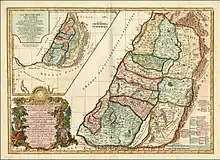

Land allotment

The Land of Israel was divided into twelve sections corresponding to the twelve tribes of Israel. However, the tribes receiving land differed from the biblical tribes. The Tribe of Levi had no land appropriation but had six Cities of Refuge under their administration as well as the Temple in Jerusalem. There was no land allotment for the Tribe of Joseph, but Joseph's two sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, received their father's land portion.

Thus the tribes receiving an allotment were:[16]

In Christianity

The twelve tribes of Israel are referred to in the New Testament. In the gospels of Matthew (19:28) and Luke (22:30), Jesus anticipates that in the Kingdom of God, his disciples will "sit on [twelve] thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel". The Epistle of James (1:1) addresses his audience as "the twelve tribes which are scattered abroad".

The Book of Revelation (7:1–8) gives a list of the twelve tribes. However, the Tribe of Dan is omitted while Joseph is mentioned alongside of Manasseh. In the vision of the Heavenly Jerusalem, the tribes' names are written on the city gates. (Revelation 21:12–13)

In Islam

The Quran (7th century CE) states that the people of Moses were split into twelve tribes. Surah 7 (Al-A'raf) verse 160 says:

"We split them up into twelve tribal communities, and We revealed to Moses, when his people asked him for water, [saying], ‘Strike the rock with your staff,’ whereat twelve fountains gushed forth from it. Every tribe came to know its drinking-place. And We shaded them with clouds, and We sent down to them manna and quails: ‘Eat of the good things We have provided you.’ And they did not wrong Us, but they used to wrong [only] themselves."[17]

Historicity

%252C_RP-P-1896-A-19368-331.jpg.webp)

For thousands of years, Christians and Jews have accepted the history of the twelve tribes as fact. Since the 19th century, however, historical criticism has examined the veracity of the historical account; whether the twelve tribes ever existed as they are described, the historicity of the eponymous ancestors, and even whether the earliest version of this tradition assumes the existence of twelve tribes.[18] The idea of twelve tribes has been described as "late Judahite" (i.e. 7th–6th century BCE). For example:

- The Blessing of Jacob (Genesis 49) directly mentions Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Zebulun, Issachar, Dan, Gad, Asher, Naphtali, Joseph, and Benjamin and especially extolls Joseph over his brothers.

- Blessing of Moses (Deuteronomy 33) mentions Benjamin, Joseph, Zebulun, Issachar, Gad, Dan, Naphtali, Asher, Reuben, Levi, and Judah, omitting Simeon.

- Judges (chapter 1) describes the conquest of Canaan; Benjamin and Simeon are mentioned in the section about Judah's exploits, and are listed alongside the Calebites and the Kenites, two Judahite clans. Joseph, Ephraim, Manasseh, Zebulun, Asher, Naphtali and Dan are mentioned, but Issachar, Reuben, Levi and Gad are not.[19]

- the Song of Deborah (Judges 5:2–31), widely acknowledged as one of the oldest passages in the Bible, mentions six of the tribes: Ephraim, Benjamin, Zebulun, Issachar, and Naphtali. Machir, a subsection of Manassah, is also mentioned. The other seven tribes are not mentioned.[20]

- Operating by the Documentary hypothesis:

- The Jahwist source relates the births of Reuben, then Simeon, Levi, and Judah. Joseph and Dinah, both appearing without birth narratives, are introduced separately in the succeeding chapters, Benjamin is introduced during the episode where Joseph's brothers seek relief from famine in Egypt, along with the notion that Joseph had "ten brethren", however, if one considers the Blessing of Jacob as having originally been a separate piece, the rest of the sons of Jacob are never named.

- The Elohist source relates the births of Dan, Naphtali, Gad, and Asher. Reuben, appearing without a birth narrative, is then described as bringing mandrakes to his mother Leah, who then gives birth to Issachar, Zebulun, Dinah, and Joseph. Simeon is introduced as the sole outcrier against his brother's plans to sell Joseph into slavery, Ephraim and Manasseh are later introduced as Joseph's sons, and even later Levi is subsequently introduced only in the narrative of Moses' birth. Judah is never mentioned.

Theories of origin

Biblical scholar Arthur Peake saw the tribes originating as postdiction, as eponymous metaphor giving an aetiology of the connectedness of the tribe to others in the Israelite confederation.[21]

Paul Davidson argued: "The stories of Jacob and his children, then, are not accounts of historical Bronze Age people. Rather, they tell us how much later Jews and Israelites understood themselves, their origins, and their relationship to the land, within the context of folktales that had evolved over time." He goes on to argue that the most of the tribal names are "not personal names, but the names of ethnic groups, geographical regions, and local deities. E.g. Benjamin, meaning "son of the south" (the location of its territory relative to Samaria), or Asher, a Phoenician territory whose name may be an allusion to the goddess Asherah."[19][22]

Immanuel Lewy in Commentary mentions "the Biblical habit of representing clans as persons. In the Bible, the twelve tribes of Israel are sons of a man called Jacob or Israel, as Edom or Esau is the brother of Jacob, and Ishmael and Isaac are the sons of Abraham. Elam and Ashur, names of two ancient nations, are sons of a man called Shem. Sidon, a Phoenician town, is the first-born of Canaan; the lands of Egypt and Abyssinia are the sons of Ham. This kind of mythological geography is widely known among all ancient peoples. Archaeology has found that many of these personal names of ancestors originally were the names of clans, tribes, localities, or nations. […] if the names of the twelve tribes of Israel are those of mythological ancestors and not of historical persons, then many stories of the patriarchal and Mosaic age lose their historic validity. They may indeed partly reflect dim reminiscences of the Hebrews' tribal past, but in their specific detail they are fiction."[23] On the same subject, Gijsbert J.B. Sulman wrote that the idea of common ancestry should be seen as "an expression of solidarity of different ethnic groups, who merged over time to form one nation", and that the practice of inventing common ancestry is also known among the Bedouin.[24]

Norman Gottwald argued that the division into twelve tribes originated as an administrative scheme under King David.[25]

Additionally, the Mesha Stele (carved c. 840 BCE) mentions Omri as King of Israel and also mentions "the men of Gad".[26][27]

Attributed coats of arms

Asher: a tree

Dan: Scales of justice

Judah: Kinnor, cithara and crown, symbolising King David

Reuben: Mandrake (Genesis 30:14)

Joseph: Palm tree and sheaves of wheat, symbolizing his time in Egypt

Naphtali: gazelle (Genesis 49:21)

Issachar: Sun, moon and stars (1 Chronicles 12:32)

Simeon: towers and walls of the city of Shechem

Benjamin: jug, ladle and fork

Gad: tents, symbolizing their itinerancy as cattle-herders

Zebulun: ship, due to their bordering the Sea of Galilee and Mediterranean

Levi: Priestly breastplate

Attributed arms are Western European coats of arms given retrospectively to persons real or fictitious who died before the start of the age of heraldry in the latter half of the 12th century.

Attributed arms of the Twelve Tribes from the Portuguese Thesouro de Nobreza, 1675

Asher

Asher Benjamin

Benjamin Dan

Dan Ephraim

Ephraim Gad

Gad Issachar

Issachar Judah

Judah Manasseh

Manasseh Naphtali

Naphtali Reuben

Reuben Simeon

Simeon Zebulun

Zebulun

See also

- Black Judaism

- Israel (the modern state, founded in 1948 CE)

- Kingdom of Israel (the northern kingdom, according to scriptural accounts, it existed from 930 to 722 BCE)

- Kingdom of Judah (the southern kingdom, according to scriptural accounts, it existing from 930 to 586 BCE)

- List of Jewish states and dynasties

- Ten Lost Tribes

References

- Genesis 35:23–26

- Genesis 41:50

- Genesis 35:22; 1 Chronicles 5:1,2; Genesis 48:5

- "In any case, it is now widely agreed that the so-called 'patriarchal/ancestral period' is a later 'literary' construct, not a period in the actual history of the ancient world. The same is the case for the ‘exodus’ and the 'wilderness period,' and more and more widely for the 'period of the Judges.'" Paula M. McNutt (1 January 1999). Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-664-22265-9.

- Alan T. Levenson (16 August 2011). The Making of the Modern Jewish Bible: How Scholars in Germany, Israel, and America Transformed an Ancient Text. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-4422-0518-5.

- "Besides the rejection of the Albrightian ‘conquest' model, the general consensus among OT scholars is that the Book of Joshua has no value in the historical reconstruction. They see the book as an ideological retrojection from a later period — either as early as the reign of Josiah or as late as the Hasmonean period." K. Lawson Younger Jr. (1 October 2004). "Early Israel in Recent Biblical Scholarship". In David W. Baker; Bill T. Arnold (eds.). The Face of Old Testament Studies: A Survey of Contemporary Approaches. Baker Academic. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-8010-2871-7.

- "It behooves us to ask, in spite of the fact that the overwhelming consensus of modern scholarship is that Joshua is a pious fiction composed by the deuteronomistic school, how does and how has the Jewish community dealt with these foundational narratives, saturated as they are with acts of violence against others?" Carl S. Ehrlich (1999). "Joshua, Judaism and Genocide". Jewish Studies at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, Volume 1: Biblical, Rabbinical, and Medieval Studies. BRILL. p. 117. ISBN 90-04-11554-4.

- "Recent decades, for example, have seen a remarkable reevaluation of evidence concerning the conquest of the land of Canaan by Joshua. As more sites have been excavated, there has been a growing consensus that the main story of Joshua, that of a speedy and complete conquest (e.g. Joshua 11:23: 'Thus Joshua conquered the whole country, just as the LORD had promised Moses') is contradicted by the archaeological record, though there are indications of some destruction and conquest at the appropriate time. Adele Berlin; Marc Zvi Brettler (17 October 2014). The Jewish Study Bible (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 951. ISBN 978-0-19-939387-9.

- "The biblical text does not shed light on the history of the highlands in the early Iron I. The conquest and part of the period of the judges narratives should be seen, first and foremost, as a Deuteronomist construct that used myths, tales, and etiological traditions in order to convey the theology and territorial ideology of the late monarchic author(s) (e.g., Nelson 1981; Van Seters 1990; Finkelstein and Silberman 2001, 72-79, Römer 2007, 83-90)." Israel Finkelstein (2013). The Forgotten Kingdom: The Archaeology and History of Northern Israel (PDF). Society of Biblical Literature. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-58983-912-0.

- "In short, the so-called ‘period of the judges’ was probably the creation of a person or persons known as the deuteronomistic historian."J. Clinton McCann (2002). Judges. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8042-3107-7.

- "Although most scholars accept the historicity of the united monarchy (although not in the scale and form described in the Bible; see Dever 1996; Na'aman 1996; Fritz 1996, and bibliography there), its existence has been questioned by other scholars (see Whitelam 1996b; see also Grabbe 1997, and bibliography there). The scenario described below suggests that some important changes did take place at the time." Avraham Faust (1 April 2016). Israel's Ethnogenesis: Settlement, Interaction, Expansion and Resistance. Routledge. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-134-94215-2.

- "In some sense most scholars today agree on a 'minimalist' point of view in this regard. It does not seem reasonable any longer to claim that the united monarchy ruled over most of Palestine and Syria." Gunnar Lebmann (2003). Andrew G. Vaughn; Ann E. Killebrew (eds.). Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period. Society of Biblical Lit. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-58983-066-0.

- "There seems to be a consensus that the power and size of the kingdom of Solomon, if it ever existed, has been hugely exaggerated." Philip R. Davies (18 December 2014). "Why do we Know about Amos?". In Diana Vikander Edelman; Ehud Ben Zvi (eds.). The Production of Prophecy: Constructing Prophecy and Prophets in Yehud. Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-317-49031-9.

- Ezekiel 47:13

- Michael Chyutin (1 January 2006). Architecture and Utopia in the Temple Era. A&C Black. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-567-03054-2.

- "The Twelve Tribes of Israel". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- al-quran.info/#7:160/1

- "Did Israel Always Have Twelve Tribes?". www.thetorah.com.

- D, Paul (July 9, 2014). "The Twelve (or So) Tribes of Israel".

- De Moor, Johannes C. (1993). "The Twelve Tribes in the Song of Deborah". Vetus Testamentum. 43 (4): 483–494. doi:10.2307/1518497. JSTOR 1518497 – via JSTOR.

- Peake's commentary on the Bible (1962) by Matthew Black, Harold Henry Rowley, and Arthur Samuel Peake - Thomas Nelson (publisher)

- Weingart, Kristin (March 1, 2019). ""All These Are the Twelve Tribes of Israel": The Origins of Israel's Kinship Identity". Near Eastern Archaeology. 82 (1): 24–31. doi:10.1086/703323 – via journals.uchicago.edu (Atypon).

- "The Study of Man: Archaeology and the Bible's Historical Truth". Commentary Magazine. May 1, 1954.

- Sulman, Gijsbert J. B. (April 12, 2016). Facts, Fiction, and the Bible: The Truth Behind the Stories in the Old Testament. Balboa Press. ISBN 9781504301121 – via Google Books.

- Gottwald, Norman (October 1, 1999). Tribes of Yahweh: A Sociology of the Religion of Liberated Israel, 1250-1050 BCE. A&C Black. ISBN 9781841270265 – via Google Books.

- "The Tribe of Gad and The Mesha Stele – TheTorah.com". www.thetorah.com.

- "Newly deciphered Moabite inscription may be first use of written word 'Hebrews'". Times of Israel.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Twelve Tribes of Israel. |