Tabernacle

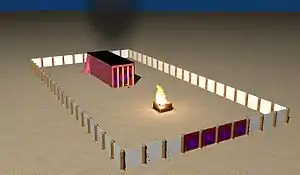

According to the Hebrew Bible, the Tabernacle (Hebrew: מִשְׁכַּן, mishkān, meaning "residence" or "dwelling place"), also known as the Tent of the Congregation (אֹ֣הֶל מוֹעֵד֩ ’ōhel mō‘êḏ, also Tent of Meeting, etc.), was the portable earthly dwelling place of Yahweh (the God of Israel) used by the Israelites from the Exodus until the conquest of Canaan. Moses was instructed at Mount Sinai to construct and transport the tabernacle[1] with the Israelites on their journey through the wilderness and their subsequent conquest of the Promised Land. After 440 years, Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem superseded it as the dwelling-place of God.

_(14781191601).jpg.webp)

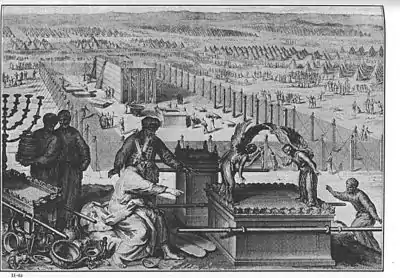

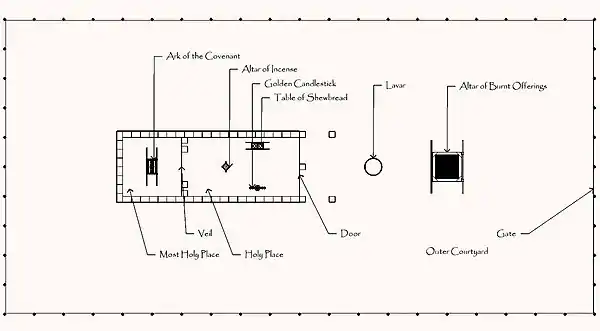

The main source describing the tabernacle is the biblical Book of Exodus, specifically Exodus 25–31 and 35–40. Those passages describe an inner sanctuary, the Holy of Holies, created by the veil suspended by four pillars. This sanctuary contained the Ark of the Covenant, with its cherubim-covered mercy seat. An outer sanctuary (the "Holy Place") contained a gold lamp-stand or candlestick. On the north side stood a table, on which lay the showbread. On the south side was the Menorah, holding seven oil lamps to give light. On the west side, just before the veil, was the golden altar of incense.[2] It was constructed of 4 woven layers of curtains and 48 15-foot tall standing wood boards overlaid in gold and held in place by its bars and silver sockets and was richly furnished with valuable materials taken from Egypt at God's command.

This description is generally identified as part of the Priestly source ("P"),[2] written in the sixth or fifth century BCE. However while the first Priestly source takes the form of instructions, the second is largely a repetition of the first in the past tense, i.e., it describes the execution of the instructions.[3] Many scholars contend that it is of a far later date than the time of Moses, and that the description reflects the structure of Solomon's Temple, while some hold that the description derives from memories of a real pre-monarchic shrine, perhaps the sanctuary at Shiloh.[2] Traditional scholars contend that it describes an actual tabernacle used in the time of Moses and thereafter.[4] According to historical criticism, an earlier, pre-exilic source, the Elohist ("E"), describes the tabernacle as a simple tent-sanctuary.[2]

Meaning

The English word tabernacle is derived from the Latin tabernāculum meaning "tent" or "hut", which in ancient Roman religion was a ritual structure.[5][6][7] The Hebrew word mishkan implies "dwell", "rest", or "to live in".[4][8] In Greek, including the Septuagint, it is translated σκηνή (skēnē), itself a Semitic loanword meaning "tent."

Description

Historical criticism has identified two accounts of the tabernacle in Exodus, a briefer Elohist account and a longer Priestly one. Traditional scholars believe the briefer account describes a different structure, perhaps Moses' personal tent.[4] The Hebrew nouns in the two accounts differ, one is most commonly translated as "tent of meeting," while the other is usually translated as "tabernacle."

Elohist account

Exodus 33:7–10 refers to "the tabernacle of the congregation" (in some translations, such as the King James Version) or "the tent of meeting" (in most modern translations),[9] which was set up outside of camp with the "cloudy pillar" visible at its door. The people directed their worship toward this center.[2] Historical criticism attributes this description to the Elohist source (E),[2] which is believed to have been written about 850 BCE or later.[10]

Priestly account

The more detailed description of a tabernacle, located in Exodus chapters 25–27 and Exodus chapters 35–40, refers to an inner shrine (the most holy place) housing the ark and an outer chamber (holy place), with a six-branch seven-lamp menorah (lampstand), table for showbread, and altar of incense.[2] An enclosure containing the sacrificial altar and bronze laver for the priests to wash surrounded these chambers.[2] This description is identified by historical criticism as part of the Priestly source (P),[2] written in the 6th or 5th century BCE.

Some scholars believe the description is of a far later date than Moses' time, and that it reflects the structure of the Temple of Solomon; others hold that the passage describes a real pre-monarchic shrine, perhaps the sanctuary at Shiloh,[2] while traditional scholars contend that it describes an actual tabernacle used in the time of Moses and thereafter.[4] This view is based on Exodus 36, 37, 38 and 39 that describe in full detail how the actual construction of the tabernacle took place during the time of Moses.[11]

The detailed outlines for the tabernacle and its priests are enumerated in the Book of Exodus:

- Exodus 25: Materials needed: the Ark, the table for 12 showbread, the menorah.

- Exodus 26: The tabernacle, the bars, partitions.

- Exodus 27: The copper altar, the enclosure, oil.

- Exodus 28: Vestments for the priests, ephod garment, ring settings, the breastplate, robe, head-plate, tunic, turban, sashes, pants.

- Exodus 29: Consecration of priests and altar.

- Exodus 30: Incense altar, washstand, anointing oil, incense.

Tent of the Presence

Some interpreters assert the Tent of the Presence was a special meeting place outside the camp, unlike the Tabernacle which was placed in the center of the camp.[12][13] According to Exodus 33:7-11, this tent was for communion with Yahweh, to receive oracles and to understand the divine will.[14] The people's elders were the subject of a remarkable prophetic event at the site of this tent in Numbers 11:24-30.[15]

Builders

In Exodus 31, the main builder and maker of the priestly vestments is specified as Bezalel, son of Uri son of Hur of the tribe of Judah, who was assisted by Oholiab and a number of skilled artisans.[3]

Plan

During the Exodus, the wandering in the desert and the conquest of Canaan the Tabernacle was in part a portable tent, and in part a wooden enclosure draped with ten curtains, of indigo (tekhelet תְּכֵלֶת), purple (argaman אַרְגָּמָן), and scarlet (shani שָׁנִי) fabric. It had a rectangular, perimeter fence of fabric, poles and staked cords. This rectangle was always erected when the Israelite tribes would camp, oriented to the east as the east side had no frames. In the center of this enclosure was a rectangular sanctuary draped with goat-hair curtains, with the roof coverings made from rams' skins.[3]

Holy of Holies

Beyond this curtain was the cube-shaped inner room, the Qṓḏeš HaQŏḏāšîm (Holy of Holies). This area housed the Ark of the Covenant, inside which were the two stone tablets brought down from Mount Sinai by Moses on which were written the Ten Commandments, a golden urn holding the manna, and Aaron's rod which had budded and borne ripe almonds. (Exodus 16:33–34, Numbers 17:1–11, Deuteronomy 10:1–5; Hebrews 9:2–5)

Tachash

Tachash is referred to fifteen times in the Hebrew Bible;[16][17] 13 of these refer to the roof coverings.

Top view, parallel projection of tabernacle.

Top view, parallel projection of tabernacle._-_Layout_and_Dimensions.jpg.webp) Tabernacle Tent dimensions according to the Book of Exodus

Tabernacle Tent dimensions according to the Book of Exodus_-_Layout_and_Dimensions_-_Full.jpg.webp) Tabernacle Tent and Courtyard dimensions according to the Book of Exodus

Tabernacle Tent and Courtyard dimensions according to the Book of Exodus

Restrictions

- Wine forbidden to priests in the tabernacle: Leviticus 10:8-15

- Individuals with the Tzaraat skin affliction were not permitted entry to the tabernacle.

- Sacrifice only at the tabernacle: Leviticus 17

There is a strict set of rules to be followed for transporting the tabernacle laid out in the Hebrew Bible. For example:

You must put the Levites in charge of the tabernacle of the Covenant, along with its furnishings and equipment. They must carry the tabernacle and its equipment as you travel, and they must care for it and camp around it. Whenever the Tabernacle is moved, the Levites will take it down and set it up again. Anyone else who goes too near the tabernacle will be executed.

Rituals

Twice a day, a priest would stand in front of the golden prayer altar and burn fragrant incense.[18] Other procedures were also carried out in the tabernacle:

- The daily meal offering: Leviticus 6:8–30

- Guilt offerings and peace offerings: Leviticus 7

- Ceremony of Ordination: Leviticus 8

- Octave of Ordination: Leviticus 9

- Yom Kippur: Leviticus 16

- Ordeal of the bitter water for suspected adulteresses: Numbers 5:11-29

- Dedication of Nazirites: Numbers 6:1-21

- Preparation of the ashes of a red heifer for the water of purification: Numbers 19

An Israelite healed of tzaraath would be presented by the priest who had confirmed his healing "at the door of the tabernacle of meeting",[19] and a woman healed of prolonged menstruation would present her offering (two turtledoves or two young pigeons) to the priest "at the door of the tabernacle of meeting".[20]

It was at the door of the tabernacle that the community wept in sorrow when all the chiefs of the people were impaled and the men who had joined in worship to the Baal of Peor were killed on God's orders.[21]

Subsequent history

During the conquest of Canaan, the main Israelite camp was at Gilgal (Joshua 4:19; 5:8–10) and the tabernacle was probably erected within the camp: Joshua 10:43ESV "…and returned into the camp" (see Numbers 1:52–2:34 "…they shall camp facing the tent of meeting on every side").

After the conquest and division of the land among the tribes, the tabernacle was moved to Shiloh in Ephraimite territory (Joshua's tribe) to avoid disputes among the other tribes (Joshua 18:1; 19:51; 22:9; Psalm 78:60). It remained there during the 300-year period of the biblical judges (the rules of the individual judges total about 350 years [1 Kings 6:1; Acts 13:20], but most ruled regionally and some terms overlapped).[22][23] According to Judges 20:26–28, the Ark, and thus possibly the tabernacle, was at Bethel while Phinehas, grandson of Aaron, was still alive.

The subsequent history of the structure is separate from that of the Ark of the Covenant. After the Ark was captured by the Philistines, King Saul moved the tabernacle to Nob, near his home town of Gibeah, but after he massacred the priests there (1 Samuel 21–22), it was moved to Gibeon, a Yahwist hill-shrine (1 Chronicles 16:39; 21:29; 2 Chronicles 1:2–6, 13).[24] Just prior to David's moving the ark to Jerusalem, the ark was located in Kiriath-Jearim (1 Chronicles 13:5–6).

The Ark was eventually brought to Jerusalem, where it was placed "inside the tent David had pitched for it" (2 Samuel 6:17; 1 Chronicles 15:1), not in the tabernacle, which remained at Gibeon. The altar of the tabernacle at Gibeon was used for sacrificial worship (1 Chronicles 16:39; 21:29; 1 Kings 3:2–4), until Solomon finally brought the structure and its furnishings to Jerusalem to furnish and dedicate the Temple. (1 Kings 8:4)

There is no mention of the tabernacle in the Tanakh after the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple by the Babylonians in c. 587 BCE.

Relationship to the golden calf

Some rabbis have commented on the proximity of the narrative of the tabernacle with that of the episode known as the sin of the golden calf recounted in Exodus 32:1-6. Maimonides asserts that the tabernacle and its accoutrements, such as the golden Ark of the Covenant and the golden Menorah were meant as "alternates" to the human weakness and needs for physical idols as seen in the golden calf episode.[25] Other scholars, such as Nachmanides disagree and maintain that the tabernacle's meaning is not tied in with the golden calf, but instead symbolizes higher mystical lessons that symbolize God's constant closeness to the Children of Israel.[26]

Blueprint for synagogues

Synagogue construction over the last two thousand years has followed the outlines of the original tabernacle.[27][28] Every synagogue has at its front an ark, aron kodesh, containing the Torah scrolls, comparable to the Ark of the Covenant which contained the tablets with Ten Commandments. This is the holiest spot in a synagogue, equivalent to the Holy of Holies.

There is also usually a constantly lighted lamp, Ner tamid, or a candelabrum, lighted during services, near a spot similar to the position of the original Menorah. At the center of the synagogue is a large elevated area, known as the bimah, where the Torah is read. This is equivalent to the tabernacle's altars upon which incense and animal sacrifices were offered. On the main holidays the priests gather at the front of the synagogue to bless the congregation as did their priestly ancestors in the tabernacle from Aaron onwards (Numbers 6:22–27).[29]

Inspiration for churches

Some Christian churches are built like a tent, to symbolize the tent of God with men, including St. Matthew Cathedral, São Mateus, Brazil, Zu den heiligen Engeln (To the Holy Angels), Hanover, Germany and the Cardboard Cathedral, Christchurch, New Zealand.[30]

New Testament and Islamic references

The tabernacle is mentioned several times in the Epistle to the Hebrews in the New Testament. For example, according to Hebrews 8:2–5 and 9:2–26 Jesus serves as the true climactic high priest in heaven, the true tabernacle, to which its counterpart on earth was a symbol and foreshadow of what was to come (Hebrews 8:5).

In the Islamic tradition, the tabernacle can relate to the Kaaba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Muslims believe this to be the House of God and the epicentre to which their entire population prays towards as one unified body.[31]

Mandaean

A Mashkhanna[32] or Beth Manda is a cultic hut and place of worship for followers of Mandaeism. A Mashkhanna must be built beside a river in order to perform maṣbuta (or baptism) and other ceremonies, because Living Water is an essential element in the Mandaean faith.[33]

See also

References

- Numbers 4:1–35

- Cross, F. L., ed. (2005). "Tabernacle". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press.

-

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Tabernacle". The Jewish Encyclopedia. 19 (2nd ed.). New York: Funk & Wagnalls. p. 419.

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Tabernacle". The Jewish Encyclopedia. 19 (2nd ed.). New York: Funk & Wagnalls. p. 419. -

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Souvay, Charles Léon (1913). "Tabernacle". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Souvay, Charles Léon (1913). "Tabernacle". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Fowler, William Warde (1922). The Religious Experience of the Roman People. London. p. 209.

- Scheid, John (2003). An Introduction to Roman Religion. Indiana University Press. pp. 113–114.

- Linderski, Jerzy (1986). "The Augural Law". Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt. II (16). pp. 2164–2288.

- "Mishkan". Strong's Concordance. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- "Exodus 33:7". Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Harris, Stephen L. (1985). Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. p. 48.

- Miller, Rabbi Avigdor (1991). A Nation is Born: Comments and Notes on Shmos. Israel Bookshop Publications. p. 231. OCLC 25242329.

- Clements, Ronald E.(1972). Exodus. New York : Cambridge University Press. Series: The Cambridge Bible Commentary: New English Bible. pp. 212-213.

- Berlin, Adele and Brettler, Marc Zvi., editors. (2014). The Jewish Study Bible. New York: Oxford University Press. 2nd edition. ISBN 9780190263898. p. 178.

- Morgenstern, Julian. (1918) “The Tent of Meeting.” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 38, p. 133. JSTOR website Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Executive Committee of the Editorial Board., Eduard König. (1906). "Tabernacle". in the Kopelman Foundation's JewishEncyclopedia,com website Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "Parsha in depth: You shall make a covering . . . of tachash skins". Chabad.

- Dr. Rabbi Norman Solomon. "What Was the Tachash Covering in the Tabernacle?". TheTorah.com.

- Exodus 30:7–10.

- Leviticus 14:11

- Leviticus 15:29

- Numbers 25:6

- Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, ed. (1987). The New American Bible, Old Testament. New York, NY: Catholic Book Publishing Co. p. 236., The Book of Judges, prefatory notes: "…The twelve judges of the present book, however, very probably exercised their authority, sometimes simultaneously, over one or another tribe of Israel, never over the entire nation."

- Chad Brand; Charles Draper; Archie England, eds. (2003). Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary. Holman Bible Publishers, Nashville, Tennessee. pp. 961–965 "Judges, Book of".: "Because of the theological nature of the narrative and the author's selective use of data, it is difficult to reconstruct the history of Israel during the period of the judges from the accounts in the heart of the book (3:7-16:31)."

- Eichrodt, Walther. (1961). Theology of the Old Testament. Philadelphia, Westminster Press. p. 111, fn3. The Internet Archive website, accessed 24 November 2019

- Maimonides (Rambam) Rabbi Mosheh ben Maimon (c. 1190) Delalatul Ha'yreen (Arabic), Moreh Nevukhim (Hebrew), Guide for the Perplexed, Part 3:32, Part 11:39, Part 111:46.

- Naḥmanides (Ramban) Rabbi Moses ben Naḥman Girondi Bonastruc ça (de) Porta (c. 1242) Bi'ur, or Perush 'al ha-Torah, Commentary on the Torah, Exodus 25:1 and Exodus Rabbah 35a.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Walter Drum (1913). "Synagogue". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Walter Drum (1913). "Synagogue". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Judaism 101: Synagogues, Shuls and Temples

-

John J. Tierney (1913). "High Priest". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

John J. Tierney (1913). "High Priest". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Anders, Johanna (2014). Neue Kirchen in der Diaspora (in German). Kassel University Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-3-86-219682-1.

- Lings, Martin (2017). Muhammad his life based on the earliest sources. Turkey: Islamic Texts Society. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-89281046-8.

- Secunda, Shai, and Steven Fine. Secunda, Shai; Fine, Steven (3 September 2012). Shoshannat Yaakov. ISBN 978-9004235441. Brill, 2012.p345

- Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2002), The Mandaeans: ancient texts and modern people, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195153859

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tabernacle. |