Typhoon Orchid (1991)

Typhoon Orchid, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Sendang, was a long-lived typhoon that brushed Japan during October 1991. An area of disturbed weather formed near the Caroline Islands in early October. A mid-latitude cyclone weakened a subtropical ridge to its north, allowing the disturbance to slowly gain latitude, and on October 3, the system organized into a tropical depression. On the next day, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Orchid. Continuing to intensify, the cyclone strengthened into a typhoon on the morning of October 6. Typhoon Orchid tracked due westward south of subtropical ridge while rapidly intensifying, and on October 7, Orchid reached its peak intensity. Shortly after its peak, the typhoon began to recurve north as the ridge receded. After interacting with Typhoon Pat, Orchid weakened below typhoon intensity on October 12. After accelerating to the northwest while gradually weakening, Orchid transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on October 14.

| Typhoon (JMA scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 4 typhoon (SSHWS) | |

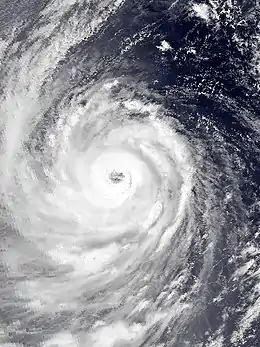

Typhoon Orchid early on October 7 | |

| Formed | October 3, 1991 |

| Dissipated | October 14, 1991 |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 175 km/h (110 mph) 1-minute sustained: 215 km/h (130 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 930 hPa (mbar); 27.46 inHg |

| Fatalities | 1 direct, 2 indirect |

| Damage | $15.8 million (1991 USD) |

| Areas affected | Guam, Japan |

| Part of the 1991 Pacific typhoon season | |

In conjunction with Pat, high waves claimed two lives on Guam. Because of the storm's slow movement as it tracked south of Japan, Typhoon Orchid dropped heavy precipitation across most of Japan. One person was killed and twenty people were injured across Japan. A total of 17 flights were cancelled while 1,072 trains were halted, stranding 342,000 passengers. In addition, 18 ferries were cancelled. The storm inflicted 249 landslides, flooded over 675 homes, and was accountable for extensive road damage in Japan. In all, damage was estimated at ¥2.15 billion (US$15.8 million).[nb 1][nb 2]

Meteorological history

The first tropical cyclone to develop during October 1991, Typhoon Orchid formed a broad monsoon trough that extended from the South China Sea eastward through the Caroline Islands. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) started monitoring the system at 06:00 UTC on October 1 while it was located northwest of Guam. A mid-latitude trough weakened a subtropical ridge to its north, allowing the tropical disturbance to slowly gain latitude. Following a surge in the monsoon trough, a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert was issued at 08:00 UTC on October 3.[1] At the same time, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) classified the system as a tropical depression,[2][nb 3] with the JTWC doing the same at 00:00 UTC on October 4.[nb 4] Post-storm analysis from the JTWC indicated, however, that the depression had attained tropical storm midday on October 3.[1] The JMA upgraded Orchid into a tropical storm early on October 4, and twenty-four hours later, the JMA upgraded Orchid into a severe tropical storm.[5] At around this time, the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) also monitored the storm and assigned it with the local name Sendang.[6] On the evening of October 5, Orchid was upgraded into a typhoon by the JTWC, and on the following morning, the JMA followed suit.[5]

Continuing to intensify, Typhoon Orchid tracked due westward south of subtropical ridge.[1] Late on October 6, the JTWC raised the intensity of the storm to 185 km/h (115 mph), equal to a Category 3 hurricane on the United States-based Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale (SSHWS).[7] Increased convergence in the southern quadrant enhanced convection, and dual outflow channels aloft were present.[1] The next day, the JTWC and JMA estimated that Orchid attained its peak intensity of 210 km/h (130 mph)[1] and 175 km/h (110 mph).[2] Shortly after its peak, Orchid began to recurve near 130°E as the ridge receded eastward, allowing Orchid to move north. Typhoon Orchid slowly accelerated after recurvature, only to slow down south of Japan on October 10 as a binary interaction started with Typhoon Pat. Over a 42-hour period from October 10–12, Orchid took a "stair-stepped” track - moving to the north then back to the northeast due to interaction with Typhoon Pat.[1] At 00:00 UTC on October 12, both the JTWC and JMA agreed that Pat lost typhoon intensity.[5] Orchid subsequently started speeding up, following Pat to the northwest while slowly weakening. At 00:00 UTC on October 13, the final warning was issued by the JTWC since Orchid had transitioned into an extratropical cyclone,[1] though according to the JMA, this process did not occur until 24 hours later.[2] The JMA stopped keeping an eye on the system late on October 15.[5]

Impact

Although Typhoon Orchid spent much of its life over the open ocean, away from land, high surf, in conjunction with Pat, killed two people on Guam on October 17. In addition, its slow movement south of Japan resulted in prolonged rains to much of the island nation.[1][8] A peak rainfall total of 762 mm (30.0 in) occurred near Tokyo.[9] A peak daily rainfall total of 307 mm (12.1 in) was recorded at Ogatsu.[10] A peak hourly rainfall total of 37 mm (1.5 in) was observed in Ōfunato.[11] A wind gust of 83 km/h (52 mph) was recorded in Tokyo.[12]

In the southern portion of the island nation, 160 households lost power in Okinawa Prefecture. Damage there amounted to ¥56.4 million.[13] Offshore Honshu, rough seas sunk the vessel Panama flag , although everyone there was rescued safely and only one person was wounded.[14] Fifty-nine roads were damaged in Nara Prefecture.[15] Forty-one trains were cancelled in Shiga Prefecture, stranding 10,000 passengers.[16] Two homes were damaged in Yokohama due to heavy rains.[17] In Hachijō-jima and Aogashima, there were a total of four landslides while in Ōshima and Nii-jima, five landslides were reported.[18] Shin-Kodaira Station was submerged underwater due to landslides, flooding 500 m (1,600 ft) of train tracks. Officials estimated it would take several months to repair the damage. Nearby, tracks were lifted 1 m (3.28 ft) due to pressure from underground water.[19] Six people were injured throughout Tokyo, where the storm resulted in ¥240 million in damage.[18] In both Owase and Ayama, one landslide occurred. Meanwhile, two landslides were reported in Nabari.[20] Roads were damaged in 295 places and embankments were damaged in 98 spots in Chiba Prefecture. A total of 995 homes were damaged, and 69 others were destroyed.[21] Six people were injured there.[22] Heavy rains damaged six homes and destroyed seven others in Yamanashi Prefecture.[23] A total of 506 houses were damaged and 31 others were destroyed in Ibaraki Prefecture. Roads there were damaged in forty-one places, forcing five roads to close.[24] Moisture from the storm, aided by a cold front, damaged 275 homes and destroyed 8 other houses in Saitama Prefecture, which resulted in 35 losing their homes. Over 300 ha (740 acres) of farmland was damaged, totaling ¥645 million.[25] Eighty-six homes were damaged in Gunma prefecture, including forty-four in Ōta, while four others were destroyed.[26] A landslide blocked a road near Katsuyama.[27] A 43-year-old woman was killed because of a landslide in Fukushima Prefecture, where six people were hurt.[28] Seventeen dwellings were damaged and destroyed in Yamagata Prefecture.[29] Heavy rains deluged Iwate Prefecture, damaging seventy-nine houses and destroying seven others. Roads suffered damage in 196 places and damage totaled at ¥657 million.[30] Damage in Aomori Prefecture was estimated at ¥557 million.[31]

Overall, one person was killed[22] and twenty people were injured across Japan.[1] A total of 17 flights were cancelled[32] while 1,072 trains were halted, which affected 342,000 passengers.[19] Eighteen ferries were cancelled.[33] The storm produced 249 landslides,[34] flooded over 675 homes, and was accountable for extensive road damage in Japan.[1] Damage was estimated at ¥2.15 billion (US$15.8 million).[13][18][25][30][31]

See also

- Typhoon Page (1990) - similar late-season Japan-hitting typhoon

Notes

- All currencies are converted from Japanese yen to United States Dollars using this with an exchange rate of the year 1991.

- All damage totals are in 1991 values of their respective currencies.

- The Japan Meteorological Agency is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the western Pacific Ocean.[3]

- Wind estimates from the JMA and most other basins throughout the world are sustained over 10 minutes, while estimates from the United States-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center are sustained over 1 minute. 10‑minute winds are about 1.14 times the amount of 1‑minute winds.[4]

References

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center (1992). Annual Tropical Cyclone Report: 1991 (PDF) (Report). United States Navy, United States Air Force. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Japan Meteorological Agency (October 10, 1992). RSMC Best Track Data – 1990–1999 (.TXT) (Report). Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- "Annual Report on Activities of the RSMC Tokyo – Typhoon Center 2000" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency. February 2001. p. 3. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Christopher W Landsea; Hurricane Research Division (April 26, 2004). "Subject: D4) What does "maximum sustained wind" mean? How does it relate to gusts in tropical cyclones?". Frequently Asked Questions:. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Kenneth R. Knapp; Michael C. Kruk; David H. Levinson; Howard J. Diamond; Charles J. Neumann (2010). 1991 ORCHID (1991274N14149). The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying tropical cyclone best track data (Report). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Old PAGASA Names: List of names for tropical cyclones occurring within the Philippine Area of Responsibility 1991–2000. Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (Report). Typhoon 2000. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Typhoon 23W Best Track (TXT) (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. December 17, 2002. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. Typhoon 19921 (Orchid). Digital Typhoon (Report). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. AMeDAS HACHIJOJIMA (44261) @ Typhoon 199121. Digital Typhoon (Report). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. AMeDAS OGATSU (34241) @ Typhoon 199121. Digital Typhoon (Report). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. AMeDAS OFUNATO (33877) @ Typhoon 199121. Digital Typhoon (Report). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. AMeDAS MIYAKEJIMA (44226) @ Typhoon 199121. Digital Typhoon (Report). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-936-09. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-817-17. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-780-18. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-761-03. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-670-06. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-662-09. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "Typhoon Triggered Landslides, Kills One, Injuries Eight". Japanese Economic Newswire. October 12, 1991. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-651-14. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-648-20. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "Tropical storm moves along Japan's coast". The Town Talk. Associated Press. October 14, 1991. Retrieved August 7, 2017. – via newspapers.com (subscription required)

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-638-09. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-629-13. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-626-10. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-624-15. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-616-08. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-595-08. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-588-03. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-584-07. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Asanobu, Kitamoto. 1991-575-04. Digital Typhoon (Report) (in Japanese). National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "Typhoon Likely to hit Honshu". Japanese Economic Newswire. October 11, 1991. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Typhoon Paralyses transport in Eastern Japan". Japanese Economic Newswire. October 13, 1991. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- Hong Kong Observatory (1992). "Part III – Tropical Cyclone Summaries". Meteorological Results: 1991 (PDF). Meteorological Results (Report). Hong Kong Observatory. p. 16. Retrieved August 3, 2017.