Fukushima Prefecture

Fukushima Prefecture (/ˌfuːkuːˈʃiːmə/; Japanese: 福島県, romanized: Fukushima-ken, pronounced [ɸɯ̥kɯɕimaꜜkeɴ]) is a prefecture of Japan located in the Tōhoku region of Honshu.[1] Fukushima Prefecture has a population of 1,848,257 (as of 1 June 2019) and has a geographic area of 13,783 square kilometres (5,322 sq mi). Fukushima Prefecture borders Miyagi Prefecture and Yamagata Prefecture to the north, Niigata Prefecture to the west, Gunma Prefecture to the southwest, and Tochigi Prefecture and Ibaraki Prefecture to the south.

Fukushima Prefecture

福島県 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese transcription(s) | |||||||||||||

| • Japanese | 福島県 | ||||||||||||

| • Rōmaji | Fukushima-ken | ||||||||||||

Flag  Symbol | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Country | |||||||||||||

| Region | Tōhoku | ||||||||||||

| Island | Honshu | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Fukushima (city) | ||||||||||||

| Subdivisions | Districts: 13, Municipalities: 59 | ||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||

| • Governor | Masao Uchibori | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| • Total | 13,783.90 km2 (5,321.99 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Area rank | 3rd | ||||||||||||

| Population (1 June 2019) | |||||||||||||

| • Total | 1,848,257 | ||||||||||||

| • Rank | 20th | ||||||||||||

| • Density | 130/km2 (350/sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | JP-07 | ||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Fukushima is the capital and Iwaki is the largest city of Fukushima Prefecture, with other major cities including Kōriyama, Aizuwakamatsu, and Sukagawa.[2] Fukushima Prefecture is located on Japan's eastern Pacific coast at the southernmost part of the Tōhoku region, and is home to Lake Inawashiro, the fourth-largest lake in Japan. Fukushima Prefecture is the third-largest prefecture of Japan (after Hokkaido and Iwate Prefecture) and divided by mountain ranges into the three regions of Aizu, Nakadōri, and Hamadōri.

History

Prehistory

The keyhole-shaped Ōyasuba Kofun is the largest kofun in the Tohoku region. The site was designated a National Historic Site of Japan in 2000.[3]

Classical and feudal period

Until the Meiji Restoration, the area of Fukushima prefecture was part of what was known as Mutsu Province.[4]

The Shirakawa Barrier and the Nakoso Barrier were built around the 5th century to protect 'civilized Japan' from the 'barbarians' to the north. Fukushima became a Province of Mutsu after the Taika Reforms were established in 646.[5]

In 718, the provinces of Iwase and Iwaki were created, but these areas reverted to Mutsu some time between 722 and 724.[6]

The Shiramizu Amidadō is a chapel within the Buddhist temple Ganjō-ji in Iwaki. It was built in 1160 and it is a National Treasure. The temple, including the paradise garden is an Historic Site.[7]

Contemporary period

This region of Japan is also known as Michinoku and Ōshū.

The Fukushima Incident, a political tumult, took place in the prefecture after Mishima Michitsune was appointed governor in 1882.

2011 earthquake and subsequent disasters

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami and the resulting Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster caused significant damage to the prefecture, primarily but not limited to the eastern Hamadōri region.

Earthquake and tsunami

On Friday, March 11, 2011, 14:46 JST, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake occurred off the coast of Miyagi Prefecture. Shindo measurements throughout the prefecture reached as high as 6-upper in isolated regions of Hama-dōri on the eastern coast and as low as a 2 in portions of the Aizu region in the western part of the prefecture. Fukushima City, located in Naka-dōri and the capital of Fukushima Prefecture, measured 6-lower.[8]

Following the earthquake there were isolated reports of major damage to structures, including the failure of Fujinuma Dam[9] as well as damage from landslides.[10] The earthquake also triggered a massive tsunami that hit the eastern coast of the prefecture and caused widespread destruction and loss of life.

In the two years following the earthquake, 1,817 residents of Fukushima Prefecture had either been confirmed dead or were missing as a result of the earthquake and tsunami.[11]

Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster

In the aftermath of the earthquake and the tsunami that followed, the outer housings of two of the six reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Ōkuma exploded followed by a partial meltdown and fires at three of the other units. Many residents were evacuated to nearby localities due to the development of a large evacuation zone around the plant. Radiation levels near the plant peaked at 400 mSv/h (millisieverts per hour) after the earthquake and tsunami, due to damage sustained. This resulted in increased recorded radiation levels across Japan.[13] On April 11, 2011, officials upgraded the disaster to a level 7 out of a possible 7, a rare occurrence not seen since the Chernobyl disaster in 1986.[14] Several months later, officials announced that although the area nearest the melt down were still off limits, areas near the twenty kilometer radial safe zone could start seeing a return of the close to 47,000 residents that had been evacuated.[15]

Geography

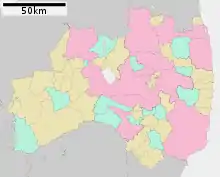

City Town Village

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 808,937 | — |

| 1890 | 952,489 | +1.65% |

| 1903 | 1,175,224 | +1.63% |

| 1913 | 1,303,501 | +1.04% |

| 1920 | 1,362,750 | +0.64% |

| 1925 | 1,437,596 | +1.08% |

| 1930 | 1,508,150 | +0.96% |

| 1935 | 1,581,563 | +0.96% |

| 1940 | 1,625,521 | +0.55% |

| 1945 | 1,957,356 | +3.79% |

| 1950 | 2,062,394 | +1.05% |

| 1955 | 2,095,237 | +0.32% |

| 1960 | 2,051,137 | −0.42% |

| 1965 | 1,983,754 | −0.67% |

| 1970 | 1,946,077 | −0.38% |

| 1975 | 1,970,616 | +0.25% |

| 1980 | 2,035,272 | +0.65% |

| 1985 | 2,080,304 | +0.44% |

| 1990 | 2,104,058 | +0.23% |

| 1995 | 2,133,592 | +0.28% |

| 2000 | 2,126,935 | −0.06% |

| 2005 | 2,091,319 | −0.34% |

| 2010 | 2,029,064 | −0.60% |

| 2015 | 1,913,606 | −1.16% |

| source:[16] | ||

Fukushima is both the southernmost prefecture of Tōhoku region and the prefecture of Tōhoku region that is closest to Tokyo. With an area size of 13,784 km2 (5,322 sq mi) it is the third-largest prefecture of Japan, behind Hokkaido and Iwate Prefecture. It is divided by mountain ranges into three regions called (from west to east) Aizu, Nakadōri, and Hamadōri.

Fukushima city is located in the Fukushima Basin's southwest area and nearby mountains. Aizuwakamatsu is located in the western part of Fukushima Prefecture, in the southeast part of Aizu basin. Mount Bandai is the highest mountain in the prefecture with an elevation of 1,819 m (5,968 ft).[17] Mount Azuma-kofuji is an active stratovolcano that is 1,705 m (5,594 ft) tall with many onsen nearby. Lake Inawashiro is the 4th largest lake of Japan (103.3 km2 (39.9 sq mi)) in the center of the prefecture.[18]

The coastal Hamadōri region lies on the Pacific Ocean and is the flattest and most temperate region, while the Nakadōri region is the agricultural heart of the prefecture and contains the capital, Fukushima City. The mountainous Aizu region has scenic lakes, lush forests, and snowy winters.

As of April 1, 2012, 13% of the total land area of the prefecture was designated as Natural Parks, namely Bandai-Asahi, Nikkō, and Oze National Parks; Echigo Sanzan-Tadami Quasi-National Park; and eleven Prefectural Natural Parks.[19]

- Gallery

View of Fukushima Basin from Hanamiyama Park

View of Fukushima Basin from Hanamiyama Park Aizu basin

Aizu basin Mount Bandai and Lake Inawashiro from Nunobiki highlands

Mount Bandai and Lake Inawashiro from Nunobiki highlands Lake Inawashiro viewed from Mount Bandai

Lake Inawashiro viewed from Mount Bandai

Cities

Thirteen cities are located in Fukushima Prefecture:

- Aizuwakamatsu

- Date

- Fukushima (capital)

- Iwaki (most populous)

- Kitakata

- Kōriyama

- Minamisōma

- Motomiya

- Nihonmatsu

- Shirakawa

- Sōma

- Sukagawa

- Tamura

Cityscape

- Gallery

Fukushima City (May 2011)

Fukushima City (May 2011) Iwaki (August 2012)

Iwaki (August 2012) Kōriyama (May 2015)

Kōriyama (May 2015) Aizuwakamatsu (May 2010)

Aizuwakamatsu (May 2010)

Mergers

List of governors of Fukushima Prefecture (from 1947)

|

|

Economy

The coastal region traditionally specializes in fishing and seafood industries, and is notable for its electric and particularly nuclear power-generating industry, while the upland regions are more focused on agriculture. Thanks to Fukushima's climate, various fruits are grown throughout the year. These include pears, peaches, cherries, grapes, and apples.[20] As of March 2011, the prefecture produced 20.6% of Japan's peaches and 8.7% of cucumbers.[21][22]

Fukushima also produces rice, that combined with pure water from mountain run-offs, is used to make sake.[23] Some sakes from the region are considered so tasteful that they are served to visiting royalty and world leaders by hosts.

Lacquerware is another popular product from Fukushima. Dating back over four hundred years, the process of making lacquerware involves carving an object out of wood, then putting a lacquer on it and decorating it. Objects made are usually dishes, vases and writing materials.[24][25]

Culture

Legend has it that an ogress, Adachigahara, once roamed the plain after whom it was named. The Adachigahara plain lies close to the city of Fukushima.

Other stories, such as that of a large, strong, red cow that carried wood, influenced toys and superstitions. The Aka-beko cow is a small, red papier-mâché cow on a bamboo or wooden frame, and is believed to ease child birth, bring good health, and help children grow up as strong as the cow.[26]

Another superstitious talisman of the region is the okiagari ko-boshi, or self-righting dharma doll. These dolls are seen as bringers of good luck and prosperity because they stand right back up when knocked down.[27]

Miharu Koma are small, wooden, black or white toy horses painted with colorful designs. Depending upon their design, they may be believed to bring things like long life to the owner.[28]

Kokeshi dolls, while less symbolic, are also a popular traditional craft. They are carved wooden dolls, with large round heads and hand painted bodies. Kokeshi dolls are popular throughout many regions of Japan, but Fukushima is credited as their birthplace.[20]

Notable festivals and events

The Nomaoi Festival horse riders dressed in complete samurai attire can be seen racing, chasing wild horses, or having contests that imitate a battle. The history behind the festival and events is over one thousand years old.[30]

During the Waraji Festival, a large (12-meter, 38-ft) straw sandal built by locals is dedicated to a shrine. There is also a traditional Taiwanese dragon dance, or Ryumai, performed by Taiwanese visitors.[32]

- Aizuwakamatsu's Aizu Festival (会津まつり, Aizu Matsuri) is held in late September[33]

The Aizu festival is a celebration of the time of the samurai. It begins with a display of sword dancing and fighting, and is followed by a procession of around five hundred people. The people in the procession carry flags and tools representing well-known feudal lords of long ago, and some are actually dressed like the lords themselves.[34]

- Taimatsu Akashi Fire Festival

A reflection of a long ago time of war, the Taimatsu Akashi Festival consists of men and women carrying large symbolic torches lit with a sacred fire to the top of Mt. Gorozan. Accompanied by drummers, the torchbearers reach the top and light a wooden frame representing an old local castle and the samurai that lived there. In more recent years the festival has been opened up so that anyone wanting to participate may carry a small symbolic torch along with the procession.[35]

- Iizaka's Fighting Festival (けんか祭り, Kenka Matsuri) is held in October[36]

- Nihonmatsu's Lantern Festival (提灯祭り, Chōchin Matsuri) is held from October 4 to 6[37]

- Nihonmatsu's Chrysanthemum doll exhibition (二本松の菊人形, Nihonmatsu no Kiku Ningyō) is held from October 1 to November 23[38]

- Kōriyama City's Uneme Festival (うねめ祭り)is held early August in honor of the legend of Princess Uneme. The festival features a large parade through the city center with thousands of contestants annually, with several festival floats and a giant taiko-drum.[39]

- Date City's Ryozen Taiko Festival (霊山太鼓祭り) is held in August and features multiple troupes of taiko drum players as well as other musical and comedic performances.[40]

Education

Universities

- Aizuwakamatsu

- Fukushima

- Fukushima Gakuin University

- Fukushima Medical University

- Fukushima University

- Iwaki

- Koriyama

- Koriyama Women's University

- Nihon University – Koriyama campus

- Ohu University

Tourism

Tsuruga castle, a samurai castle originally built in the late 14th century, was occupied by the region's governor in the mid-19th century, during a time of war and governmental instability. Because of this, Aizuwakamatsu was the site of an important battle in the Boshin War, during which 19 teenage members of the Byakkotai committed ritual seppuku suicide. Their graves on Mt. Iimori are a popular tourist attraction.[23]

Kitakata is well known for its distinctive Kitakata ramen noodles and well-preserved traditional storehouse buildings, while Ōuchi-juku in the town of Shimogo retains numerous thatched buildings from the Edo period.

Mount Bandai, in the Bandai-Asahi National Park, erupted in 1888, creating a large crater and numerous lakes, including the picturesque 'Five Coloured Lakes' (Goshiki-numa). Bird watching crowds are not uncommon during migration season here. The area is popular with hikers and skiers. Guided snowshoe tours are also offered in the winter.[41]

The Inawashiro Lake area of Bandai-Asahi National Park is Inawashiro-ko, where the parental home of Hideyo Noguchi (1876–1928) can still be found. It was preserved along with some of Noguchi's belongings and letters as part of a memorial. Noguchi is famous not only for his research on yellow fever, but also for having his face on the 1,000 yen note.[42]

The Miharu Takizakura is an ancient weeping higan cherry tree in Miharu, Fukushima. It is over 1,000 years old.

Food

Fruits. Fukushima is known as a "Fruit Kingdom"[43] because of its many seasonal fruits, and the fact that there is fruit being harvested every month of the year.[43] While peaches are the most famous, the prefecture also produces large quantities of cherries, nashi (Japanese pears), grapes, persimmons, and apples.

Fukushima-Gyu is the prefecture's signature beef. The Japanese Black type cattle used to make Fukushima-Gyu are fed, raised, and processed within the prefecture. Only beef with a grade of 2 or 3 can be labeled as "Fukushima-Gyu" (福島牛)[44]

Ikaninjin is shredded carrot and dried squid seasoned with soy sauce, cooking sake, mirin, etc. It is a local cuisine from the northern parts of Fukushima Prefecture. It is primarily made from the late autumn to winter in the household.[45]

Kitakata Ramen is one of the Top 3 Ramen of Japan, along with Sapporo and Hakata.[46] The base is a soy-sauce soup, as historically soy sauce was readily available from the many storehouses around the town. Niboshi (sardines), tonkotsu (pig bones) and sometimes chicken and vegetables are boiled to make the stock. This is then topped with chashu (thinly sliced barbeque pork), spring onions, fermented bamboo shoots, and sometimes narutomaki, a pink and white swirl of cured fish cake.[46]

Mamador is the prefecture's most famous confection.[47] The baked good has a milky red bean flavor center wrapped in a buttery dough. The name means “People who drink mothers’ milk" in Spanish.[48] It is produced by the Sanmangoku Company.

Creambox is prefecture's second famous confection. It is a sweet bread with a thick milk bread and white milk-flavored cream. It is sold in Koriyama City at many bakery and school purchases . The selling price is usually around 100 yen, and in some rare cases, the dough is round. Since it looks simple and does not change much from normal bread when viewed from above, some processing may be performed on the cream, there are things that put almonds or draw the character's face with chocolate [49]

Sake. The Fukushima Prefecture Sake Brewers Cooperative is made up of nearly 60 sake breweries.[50] Additionally, the Annual Japan Sake Awards has awarded the prefecture the most gold prizes of all of Japan for four years running as of 2016.[51]

Transportation

Rail

Expressways

National highways

National Route 4

National Route 4 National Route 6

National Route 6 National Route 13 (Fukushima-Yamagata-Shinjo-Yokote-Akita)

National Route 13 (Fukushima-Yamagata-Shinjo-Yokote-Akita) National Route 49

National Route 49 National Route 113 (Niigata-Murakami-Nagai-Nanyo-Shiroishi-Soma)

National Route 113 (Niigata-Murakami-Nagai-Nanyo-Shiroishi-Soma) National Route 114

National Route 114 National Route 115 (Soma-Fukushima-Inawashiro)

National Route 115 (Soma-Fukushima-Inawashiro) National Route 118

National Route 118 National Route 121

National Route 121 National Route 252

National Route 252 National Route 288

National Route 288 National Route 289 (Niigata-Tsubame-Uonuma-Tadami-Shirakawa-Iwaki)

National Route 289 (Niigata-Tsubame-Uonuma-Tadami-Shirakawa-Iwaki) National Route 294

National Route 294 National Route 349 (Mito-Hitachiota-Iwaki-Tamura-Nihonmatsu-Date-Shibata)

National Route 349 (Mito-Hitachiota-Iwaki-Tamura-Nihonmatsu-Date-Shibata) National Route 352

National Route 352 National Route 399

National Route 399 National Route 400

National Route 400 National Route 401 (Niigata-Agano-Kitakata-Fukushima-Namie)

National Route 401 (Niigata-Agano-Kitakata-Fukushima-Namie) National Route 459

National Route 459

Ports

- Onahama Port – International and domestic goods, container hub port in Iwaki

Airports

Notable people

- Junko Tabei, the first woman to reach the summit of Mount Everest, and the first woman to ascend all Seven Summits by climbing the highest peak on every continent

- Takeshi Suzuki, an alpine skier and Paralympic athlete.

- Yoshihide Muroya, an aerobatics pilot and race pilot

- Toshiyuki Nishida, an actor best known for his fishing comedy series, Tsuribaka Nisshi ("The Fishing Maniac's Diary")

- Wakatakakage Atsushi, a professional sumo wrestler competing in sumo's top makuuchi division beginning in 2019.

- Mazie K. Hirono, US Senator and former Lieutenant Governor for Hawaii, was born in Fukushima Prefecture in 1947, and moved to Hawaii in 1955

- Hideyo Noguchi, the doctor who contributed to knowledge in the fight against syphilis and yellow fever. The Japanese government created the Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize in his honor. This was first awarded in May 2008[52]

- Seishiro Okazaki (January 28, 1890 – July 12, 1951) was a Japanese American healer, martial artist, and founder of Danzan-ryū jujitsu. Born in Kakeda, Date County in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, he immigrated to Hawaii in 1906[53]

Notes

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Fukushima-ken" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 218, p. 218, at Google Books; "Tōhoku" in p. 970, p. 970, at Google Books

- Nussbaum, "Fukushima" in p. 218, p. 218, at Google Books

- "大安場古墳群" (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs.

- Nussbaum, "Provinces and prefectures" in p. 780, p. 780, at Google Books

- Takeda, Toru et al. (2001). Fukushima – Today & Tomorrow, p. 10.

- Meyners d'Estrey, Guillaume Henry Jean (1884). Annales de l'Extrême Orient et de l'Afrique, Vol. 6, p. 172, p. 172, at Google Books; Nussbaum, "Iwaki" in p. 408, p. 408, at Google Books

- "Database of Registered National Cultural Properties". Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on December 23, 2019. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- "Felt earthquakes" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- "東北・関東7県で貯水池、農業用ダムの損傷86カ所 補修予算わずか1億、不安募る梅雨". msn産経ニュース. Archived from the original on August 26, 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- "新たに女性遺体を発見 白河の土砂崩れ". 47NEWS. Archived from the original on November 25, 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- "Damage Situation and Police Countermeasures... March 11, 2013" National Police Agency of Japan. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- Martin Fackler (June 1, 2011). "Report Finds Japan Underestimated Tsunami Danger". New York Times.

- "Japan quake: Radiation rises at Fukushima nuclear plant". BBC News. March 15, 2011.

- "Fukushima crisis raised to level 7, still no Chernobyl". New Scientist. April 12, 2011.

- "Fukushima accident". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- Statistics Bureau of Japan

- "Bandai". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- Campbell, Allen; Nobel, David S (1993). Japan: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha. p. 598. ISBN 406205938X.

- "General overview of area figures for Natural Parks by prefecture" (PDF). Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- "Fukushima City". Japan National Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on September 25, 2017.

- Schreiber, Mark, "Japan's food crisis goes beyond recent panic buying Archived April 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine", The Japan Times, April 17, 2011, p. 9.

- Hongo, Jun, "Fukushima not just about nuke crisis", The Japan Times, March 20, 2012, p. 3.

- "Aizuwakamatsu Area". Japan National Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on July 14, 2017.

- "Aizu lacquerware". Fukushima Prefecture Tourism & Local Products Association. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- "Make Your Own Aizu Lacquerware Chopsticks". Rediscover Fukushima. June 20, 2018. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- "Akabeko Red Cows". Fukushima Prefecture Tourism & Local Products Association. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- "Okiagari Ko-boshi (self-righting dharma doll)". Fukushima Prefecture Tourism & Local Products Association. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- "Miharu Koma". Fukushima Prefecture Tourism & Local Products Association. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- "Soma Nomaoi Executive Committee Official Site". Soma Nomaoi Executive Committee. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- "The Soma Nomaoi". Fukushima Prefecture Tourism & Local Products Association. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- わらじまつり (in Japanese). 福島わらじまつり実行委員会事務局. Archived from the original on December 4, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- "Fukushima Waraji Festival". Fukushima Prefecture Tourism & Local Products Association. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- 会津まつり 先人感謝祭・会津藩公行列 (in Japanese). 会津若松観光物産協会. Retrieved March 20, 2012.

- "Aizu Festival". Fukushima Prefecture Tourism & Local Products Association. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- "Taimatsu Akashi". Fukushima Prefecture Tourism & Local Products Association. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- けんか祭りの飯坂八幡神社 (in Japanese). Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- 二本松の提灯祭り (in Japanese). Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- 二本松の菊人形 (in Japanese). 二本松菊栄会. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- "第53回郡山うねめまつり2017". www.ko-cci.or.jp. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- 霊山太鼓保存会. 太鼓まつり|霊山太鼓. www5e.biglobe.ne.jp (in Japanese). Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- "Ura-bandai Area". Japan National Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on August 15, 2017.

- "Lake Inawashiro Area". Japan National Tourism Organization. Archived from the original on November 10, 2017.

- "フルーツを食す – 福島市ホームページ". www.city.fukushima.fukushima.jp. Archived from the original on October 24, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- "福島牛販売促進協議会". www.fukushima-gyu.com. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- 羽雁渉「イカと日本人」Chunichi Newspaper, Sunday edition.世界と日本 大図解シリーズ No.1272. October 9, 2016 、pages 1, 8 (in Japanese).

- "Kitakata ramen". NHK WORLD. June 20, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- "福島の人気お土産50選|ままどおるだけじゃない!福島のおすすめお菓子-カウモ". カウモ. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- "ままどおる|三万石". www.sanmangoku.co.jp. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- "クリームボックス|クリームボックス部". creamboxbu.wordpress.com. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- "蔵元検索 | 福島県酒造協同組合". sake-fukushima.jp. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- "祝!!4連覇 平成27酒造年度全国新酒鑑評会金賞受賞蔵数 日本一!! | 福島県酒造協同組合". sake-fukushima.jp. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- "Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize". Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- [Immigration records show he arrived at the port of Honolulu T.H. on October 9, 1906 aboard the Steamer "China" of the Pacific Mail S.S. Co. "Hawaii, Honolulu Index to passengers, Not Including Filipinos, 1900–1952". FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org: accessed June 25, 2011). entry for Akaraki Seisiro, age 16; citing Passenger Records, Aada, Matsusuke – Arisuye, Tomoyashe, Image 2150; National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C., United States.]

References

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 58053128

- Takeda, Toru; Hishinuma, Tomio; Oguma, Chiyoichi; Takiguchi, R. (July 7, 2001). Fukushima – Today & Tomorrow. Aizu-Wakamatsu City: Rekishi Shunju Publishing Co. ISBN 4-89757-432-3.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Fukushima (prefecture). |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fukushima prefecture. |

| Wikinews has news related to: |

- Fukushima Prefecture Official Website (in Japanese)