United States Army Air Service

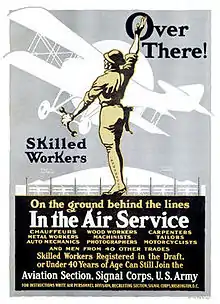

The United States Army Air Service (USAAS)[1] (also known as the "Air Service", "U.S. Air Service" and before its legislative establishment in 1920, the "Air Service, United States Army") was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1918 and 1926 and a forerunner of the United States Air Force. It was established as an independent but temporary branch of the U.S. War Department during World War I by two executive orders of President Woodrow Wilson: on May 24, 1918, replacing the Aviation Section, Signal Corps as the nation's air force; and March 19, 1919, establishing a military Director of Air Service to control all aviation activities.[2] Its life was extended for another year in July 1919, during which time Congress passed the legislation necessary to make it a permanent establishment. The National Defense Act of 1920 assigned the Air Service the status of "combatant arm of the line" of the United States Army with a major general in command.[3]

| United States Army Air Service | |

|---|---|

"Prop and Wings" branch insignia of the Air Service | |

| Active | May 24, 1918 – July 2, 1926 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Air force |

| Role | Aerial warfare |

| Size | 195,024 men, 7,900 aircraft (1918) 9,954 men, 1,451 aircraft (1926) |

| Garrison/HQ | Munitions Building, Washington, D.C. |

| Engagements | World War I |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Mason Patrick |

In France, the Air Service of the American Expeditionary Force, a separate entity under commanding General John J. Pershing that conducted the combat operations of U.S. military aviation, began field service in the spring of 1918. By the end of the war, the Air Service used 45 squadrons to cover 137 kilometers (85 miles) of front from Pont-à-Mousson to Sedan. 71 pursuit pilots were credited with shooting down five or more German aircraft while in American service. Overall the Air Service destroyed 756 enemy aircraft and 76 balloons in combat. 17 balloon companies also operated at the front, making 1,642 combat ascensions. 289 airplanes and 48 balloons were lost in battle.

The Air Service was the first form of the air force to have an independent organizational structure and identity. Although officers concurrently held rank in various branches, after May 1918 their branch designation in official correspondence while on aviation assignment changed from "ASSC" (Aviation Section, Signal Corps) to "AS, USA" (Air Service, United States Army).[4] After July 1, 1920, its personnel became members of the Air Service branch, receiving new commissions. During the war its responsibilities and functions were split between two coordinate agencies, the Division of Military Aeronautics (DMA) and the Bureau of Aircraft Production (BAP), each reporting directly to the Secretary of War, creating a dual authority over military aviation that caused unity of command difficulties.

The seven-year history of the post-war Air Service was marked by a prolonged debate between adherents of airpower and the supporters of the traditional military services about the value of an independent Air Force. Airmen such as Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell supported the concept. The Army's senior leadership from World War I, the United States Navy, and the majority of the nation's political leadership favored integration of all military aviation into the Army and Navy. Aided by a wave of pacifism following the war that drastically cut military budgets, opponents of an independent air force prevailed. The Air Service was renamed the Army Air Corps in 1926 as a compromise in the continuing struggle.

Creation of the Air Service

Background of the wartime Air Service

Although war in Europe prompted Congress to vastly increase the appropriations for the Aviation Section in 1916, it nevertheless tabled a bill proposing an aviation department incorporating all aspects of military aviation. The declaration of war against Germany on April 6, 1917, putting the United States in World War I, came too quickly (less than eight months after its use in Mexico chasing Pancho Villa) to solve emerging engineering and production problems. The reorganization of the Aviation Section had been inadequate in resolving problems in training, leaving the United States totally unprepared to fight an air war in Europe. The Aviation Section consisted of 131 officers, 1087 enlisted men, and approximately 280 airplanes.[5][n 1]

The administration of President Woodrow Wilson created an advisory Aircraft Production Board in May 1917, consisting of members of the Army, Navy and industry, to study the Europeans' experience in aircraft production and the standardization of aircraft parts. The Board dispatched Major Raynal C. Bolling, a lawyer and military aviation pioneer, together with a commission of over 100 members, to Europe in the summer of 1917 to determine American aircraft needs, recommend priorities for acquisition and production, and negotiate prices and royalties.[6] Congress passed a series of legislation in the next three months that appropriated huge sums for development of military aviation, including the largest single appropriation for a single purpose to that time, $640 million[n 2] in the Aviation Act (40 Stat. 243), passed July 24, 1917.[7][n 3] By the time the bill passed, the term Air Service was in widespread if unofficial usage to collectively describe all aspects of Army aviation.[8]

Although it considered creation of a separate aviation department to act as the centralized authority for decision-making, both the War and the Navy Departments opposed it, and on October 1, 1917, Congress instead legalized the existence of the APB and changed its name to the "Aircraft Board", transferring its functions from the Council of National Defense to the secretaries of War and the Navy.[9] Even so, the Aircraft Board in practice had little control over procurement contracts and functioned mostly as an information provider between industrial, governmental, and military entities. Nor did the "Equipment Division" of the Signal Corps exercise such control. Established by the Office of the Chief Signal Officer (OCSO) as one of the operating components of the Aviation Section, its task was to unify and coordinate the various agencies involved but its head was a commissioned former member of the APB who did nothing to create any effective coordination.[10] Moreover, the largely wood and fabric airframe designs of World War I did not lend themselves to being made with the mass production methods of the automotive industry, which used considerable amounts of metallic materials instead, and the priority of mass-producing spare parts was neglected. Though individual areas within the aviation industry responded well, the industry as a whole failed. Efforts to mass-produce European aircraft under license largely failed because the aircraft, made by hand, were not amenable to the more precise American manufacturing methods. At the same time the Aeronautical Division of the OCSO was renamed the Air Division with continued responsibility for training and operations but with no influence on acquisition or doctrine. In the end the decision-making process in aircraft procurement was badly fragmented and production on a large scale proved impossible.[10]

Aircraft production failures

The Aircraft Board came under severe criticism for failure to meet goals or its own claims of aircraft production, followed by a highly publicized personal investigation by Gutzon Borglum, a harshly vocal critic of the board. Borglum had exchanged letters with President Wilson, a personal friend, from which he assumed an appointment to investigate had been authorized, which the administration soon denied.[11] Both the U.S. Senate and the Department of Justice began investigations into possible fraudulent dealings. President Wilson also acted by appointing a Director of Aircraft Production on April 28, 1918, and abolished the Air Division of the OCSO, creating a Division of Military Aeronautics (DMA) with Brigadier General William L. Kenly brought back from France to be its head, to separate supervision of aviation from the duties of the Chief Signal Officer. Less than a month later, Wilson used a war powers provision of the Overman Act of May 20, 1918, to issue Executive Order No. 2862 that suspended for the duration of the war plus six months the statutory responsibilities of the Aviation Section and removed the DMA entirely from the Signal Corps (reporting directly to the Secretary of War). The DMA was assigned the function of procuring and training a combat force. In addition, the executive order created a Bureau of Aircraft Production (BAP), a military organization with a civilian director, as a separate executive bureau to provide the aircraft needed.[1][12]

This arrangement lasted only until the War Department implemented the executive order on May 24 by issuing General Order No. 51 to coordinate the two independent agencies, with an eventual goal of creating a Director of Air Service.[13] (The term "Air Service" had been in use in France since June 13, 1917, to describe the function of aviation units attached to the American Expeditionary Force.) It delayed the appointment of a director as long as the BAP operated as a separate executive bureau. In August, the Senate completed its investigation of the Aircraft Board, and while it found no criminal culpability, it reported that massive waste and delay in production had occurred. As a result, the Director of Aircraft Production (who was also chairman of the Aircraft Board), John D. Ryan, was appointed to the vacant position of Second Assistant Secretary of War and designated as Director of Air Service, nominally in charge of the DMA.[1] The Department of Justice report followed two months later and also blamed the delays on administrative and organizational deficiencies in the Aviation Section. Ryan's appointment came too late for any effective consolidation of both agencies,[14][n 4] continuing an obstructive division of authority that was never resolved during the war.[15]

Following the Armistice, Ryan resigned on November 27, leaving both the BAP and DMA, as well as the original Aircraft Board, leaderless. In addition certain powers, primarily those of dealing legally with the government-owned Spruce Production Corporation, had been delegated to Ryan by name, not to his position as Director of Aircraft Production, and as such could not be legally conferred on any successor. Maj. Gen. Charles Menoher was appointed to the vacancy on January 2, 1919, but the patchwork nature of laws and executive orders that had created the various parts of the Air Service prevented him from exercising all their legal powers and ending the unity of command problems caused by dual authority.[16][17]

Pilot training

The United States began the World War with 35 pilots and 51 student pilots on its rosters.[18] Like the rest of the Army, the Aviation Section concluded that training Reserve officers was the solution to its manpower needs and sent a panel of three representatives from each of six U.S. universities to Toronto from 7 to 11 May 1917 to study Canada's pilot training program. The Chief Signal Officer assigned Major Hiram Bingham III, an adventurer and reserve officer on the faculty of Yale, to organize a training program on the Canadian model. A three-phase Flying Cadet[n 5] program came into being, and although systematic, pressing needs for manpower saw many overlaps of the phases.[19]

The first phase was an eight-week ground school course conducted by the Schools of Military Aeronautics Division, organized at the six (later eight) American universities,[n 6] and commanded by Bingham. The first class at the ground schools began 21 May 1917 and concluded 14 July 1917, graduating 147 cadets and enrolling another 1,430.[20][n 7] By mid-November, 3,140 had graduated and more than 500 had become rated officers.[21]

Out of more than 40,000 applicants, 22,689 were accepted and 17,540 completed ground school training.[22] Approximately 15,000 advanced to primary (preliminary) flying training, a six-to-eight week course[n 8] conducted by both military and civilian flying instructors, using variants of the Curtiss Jenny as the primary trainer. Primary flying training school usually produced a candidate for commissioning in 15 to 25 hours of flight. At the assurance of the French that they could be rapidly trained in all phases, 1,700 cadets who had graduated from ground school were sent to Europe to undertake the entire flying portion of their training in Great Britain, France, and Italy. In December 1917, after receiving 1,400 of the cadets, the French requested that further movement of cadets be halted because of training backlogs of as much as six months, and no further student pilots were sent to France until they had completed their primary training and been commissioned. During the backlog, more than 1,000 cadets were used as cooks, guards, laborers and other menial jobs, while paid at cadet salary (in the grade and rank of private first class), for which they became derisively known as the "Million-Dollar Guard".[23][n 9] The backlog was finally cleared by opening an Air Service primary school at Tours and devoting part of the advanced school at Issoudun to preliminary training for a period of time.

The U.S. training program produced more than 10,000 pilots as new first lieutenants in the Signal Officers Reserve Corps (S.O.R.C.). 8,688 received ratings of Reserve Military Aviator in the United States and were assigned to newly created squadrons or as instructors.[24] 1,609 more were commissioned in Europe,[25][n 10] with their commissions backdated in February and March 1918 to those of their peers trained in the United States.[26] Pilots in Europe completed an advanced phase in which they received specialized training in pursuit, bombing, or observation at Air Service schools acquired from the French at Issoudun, Clermont-Ferrand, and Tours, respectively.[27]

By November 11, 1918, the Air Service both overseas and domestically had 195,024 personnel (20,568 officers; 174,456 enlisted men) and 7,900 aircraft,[28] constituting five per cent of the United States Army.[29] 32,520 personnel served in the Bureau of Aircraft Production and the remainder in the Division of Military Aeronautics. The Air Service commissioned over 17,000 reserve officers. More than 10,000 mechanics were trained to service the American aircraft fleet.[30] Of aircraft manufactured in America, the de Havilland DH-4B (3,400) was the most numerous, although only 1,213 were shipped overseas, and only 1,087 of those assembled,[31] most used in observation units. The facilities of the Air Service in the United States totaled 40 flying fields, 8 balloon fields, 5 schools of military aeronautics,[n 11] 6 technical schools, and 14 aircraft depots. 16 additional training schools were located in France, and officers also trained at three schools operated by the Allies.[32]

A byproduct of the training program was the creation of the American airmail system. On May 3, 1918, Col. Henry H. Arnold, Assistant Director of the DMA, was ordered to put together a daily route for moving mail by airplane between New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. He assigned the task to the Executive Officer for Flying Training, Major Reuben H. Fleet. The Air Service, using six pilots (four instructor pilots and two new graduates) and six Curtiss JN-4H "Jenny" trainers modified to carry mail, began the mail service on May 15. It later extended the route to Boston and added Curtiss R-4LMs to its small fleet, carrying mail until August 12, 1918, when the U.S. Post Office took over.[33]

Air Service of the AEF

Organization

Sent to Europe in March 1917 as an observer, Lieutenant Colonel Billy Mitchell arrived in Paris just four days after the United States declared war[34] and established an office for the American "air service." Upon his arrival in France in June 1917, American Expeditionary Force commanding general John J. Pershing met with Mitchell, who advised Pershing that his office was ready to proceed with any project Pershing might require.[35] Pershing's aviation officer, Major Townsend F. Dodd, first used the term "Air Service" in a memo to the chief of staff of the AEF on 20 June 1917.[36] The term also appeared on July 5, 1917, in AEF General Order (G.O.) No. 8, in tables detailing staff organization and duties.[37] Mitchell replaced Dodd on 30 June 1917, with the position renamed "Chief of Air Service" and its duties described. After Mitchell was superseded in September by Kenly, he remained as ex officio chief through his influence on Kenly as Air Commander, Zone of the Advance (ACA).

The Air Service, American Expeditionary Forces was formally created on 3 September 1917 by the publication of AEF G.O. No. 31 and remained in being until demobilized in 1919.[2] Kenly, an artillery officer, had been a student the previous winter in the Field Officers Course at the Aviation School in San Diego, then served as executive officer of the school to gain administrative experience in aviation matters. Mitchell, Bolling and Dodd were promoted to colonel and given senior positions in the Air Service hierarchy. Bolling was made Director of Air Service Supply (DASS) to administer the "Zone of the Line of Communications" (sic), later called the Service of Supply, and Dodd was named Director of Air Service Instruction (DAI). Kenley proved to be only an interim commander, as Brig. Gen. Benjamin Foulois replaced him on 27 November 1917, arriving in France with a large but untrained staff of non-aviators. This resulted in considerable resentment from Mitchell's smaller staff already in place, many of whom in key positions, including Bolling, Dodd and Lt. Col. Edgar S. Gorrell, were immediately displaced.[38] Mitchell, however, was not replaced and became a source of persistent discord with Foulois.

Pershing restated the responsibilities of the Air Service AEF with G.O. No. 81, May 29, 1918, in which he replaced Foulois as Chief of Air Service AEF with a West Point classmate and non-aviator, Major General Mason Patrick. Air Service staff planning had been inefficient, with considerable internal dissension as well as conflict between its members and those of Pershing's General Staff. Aircraft and unit totals lagged far behind those promised in 1917. Officers in the combat units balked at taking orders from Foulois' non-flying staff. Considerable house-cleaning of the existing staff resulted from Patrick's appointment, bringing in experienced staff officers to administrate, and tightening up lines of communication.[39][n 12]

Pershing had in September 1917 called for creation of 260 U.S. air combat squadrons by December 1918, but slowness of the buildup reduced that on August 17, 1918, to a final plan for 202 by June 1919.[40] In Pershing's view, the two functions of the AEF's Air Service were to repel German aircraft and conduct observation of enemy movements. The heart of the proposed force would be its 101 observation squadrons (52 corps observation and 49 army observation), to be distributed to three armies and 16 corps. In addition, 60 pursuit squadrons, 27 night-bombardment squadrons, and 14 day-bombardment squadrons were to conduct supporting operations.[41]

Without the time or infrastructure in the United States to equip units to send overseas using aircraft designed and built in the U.S., the AEF Air Service acquired Allied aircraft designs already in service with the French and British air services. On August 30, 1917, the American and French governments agreed to a contract for the purchase of 1,500 Breguet 14 B.2 bombers-reconnaissance planes; 2,000 SPAD XIII and 1,500 Nieuport 28 pursuits for delivery by July 1, 1918. By the armistice, the AEF actually received 4,874 aircraft from the French, in addition to 258 from Great Britain, 19 from Italy, and 1,213 of American manufacture, for a total of 6,364 airplanes. 1,664 were classed as training craft.[31]

The United States recognized that French skilled labor was severely limited by war casualties, and promised to train and deploy 7,000 automobile mechanics to aid the French Motor Transport Corps. In December 1917 the Aviation Section developed a maintenance organization of four large units termed Motor Mechanics Regiments, Signal Corps, each regiment consisting of four battalions of five companies totaling more than 3,600 men. The key innovative element was the use of junior officers recruited from the automobile industry as "technical officers" to supervise maintenance. In February 1918, Colonel S.D. Waldon of the Signal Corps returned from observing British factory and field methods in aviation operations, just as the Bureau of Aircraft Production concluded that the French were unable to meet their aircraft production goals. Waldon recommended that the regiments be reorganized for aircraft instead of automobile mechanics. The change came too late to affect the 1st and 2nd Regiments, which landed in France in March 1918, but both the 3rd and 4th Regiments reorganized, delaying their deployment until the end of July. By the Armistice all four regiments were configured as aircraft repair and maintenance units, and designated Air Service Mechanics Regiments.

The primary aircraft used by the AEF at the front (the "Zone of Advance") were the SPAD XIII (877), Nieuport 28 (181), and SPAD VII (103) as pursuit aircraft, the DeHaviland DH-4B (696) and Breguet 14 (87) for daylight bombing, and the DH-4 and Salmson 2 A.2 (557) for observation and photo reconnaissance. The SE-5 operated as the main trainer for the Air Service. Balloon companies operated the French-designed Goodyear Type R, a winch-tethered, hydrogen-filled, captive "Caquot" observation balloon of 32,200 cubic-foot (912 cubic meters) capacity, deploying one balloon per company.[n 13]

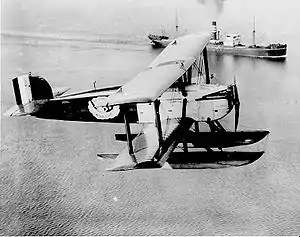

The United States adopted a national insignia for all military aircraft in May 1917 using the colors specified for the U.S. flag, consisting of a white five-pointed star inside of a blue circumscribed circle, with a red circle in the center of the star having a diameter tangent to the pentagon of the interior points of the star. The insignia was ordered painted on both wingtips of the upper surface of the top wing, the lower surface of bottom wings, and the fuselage of all Army aircraft on 17 May 1917. However due to concerns about confusion with the markings of enemy aircraft, in early 1918 a red, blue, and white roundel similar to those used by the Allied Powers, in the former color arrangement of the defunct Imperial Russian Air Service, was instead ordered painted on all U.S. aircraft operating in Europe, remaining in effect until 1919.[42][n 14][43]

On May 6, 1918 Foulois established a policy authorizing creation of emblems for aviation units, and ordered all squadrons to create an official insignia to be painted on each side of an airplane fuselage: "The squadron will design their own insignia during the period of organizational training. The design must be submitted to the Chief of Air Service, AEF, for approval. The design should be simple enough to be recognizable from a distance."[44][n 15]

"Firsts"

The first U.S. aviation squadron to reach France was the 1st Aero Squadron, which sailed from New York in August 1917 and arrived at Le Havre on September 3. A member of the squadron, Lt. Stephen W. Thompson, achieved the first aerial victory by the U.S. military while flying as a gunner-observer with a French day bombing squadron on February 5, 1918.[45] As other squadrons were organized, they were sent overseas, where they continued their training. The first U.S. squadron to see combat, on February 19, 1918, was the 103rd Aero Squadron, a pursuit unit flying with French forces and composed largely of former members of the Lafayette Escadrille and Lafayette Flying Corps. The first U.S. aviator killed in action during aerial combat occurred March 8, 1918, when Captain James E. Miller, commanding the 95th Pursuit Squadron, was shot down while on a voluntary patrol near Reims.[n 16] The first aerial victory in an American unit was by 1st Lt. Paul F. Baer of the 103rd Aero Squadron, and formerly a member of the Lafayette Flying Corps, on March 11. The first victories credited to American-trained pilots came on April 14, 1918, when Lieutenants Alan F. Winslow and Douglas Campbell of the 94th Pursuit Squadron scored.[46][n 17] The first mission by an American squadron across the lines occurred April 11, when the 1st Aero Squadron, led by its commander, Major Ralph Royce, flew a photo reconnaissance mission to the vicinity of Apremont.[45]

The first American balloon group arrived in France on December 28, 1917. It separated into four companies that were assigned individually to training centers and instructed in French balloon procedures, then equipped with Caquot balloons, winches, and parachutes. The 2d Balloon Company[n 18] joined the French 91st Balloon Company at the front near Royaumeix on February 26, 1918.[47] On March 5 it took over the line and began operations supporting the U.S. 1st Division, becoming the "first complete American Air Service unit in history to operate against an enemy on foreign soil."[48]

Units and tactics

By the beginning of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive the Air Service AEF consisted of 32 squadrons (15 pursuit, 13 observation, and 4 bombing) at the front,[49] while by November 11, 1918, 45 squadrons (20 pursuit,[n 19] 18 observation,[n 20] and 7 bombardment[n 21]) had been assembled for combat. During the war, these squadrons played important roles in the Battle of Château-Thierry, the St-Mihiel Offensive, and the Meuse-Argonne. Several units, including the 94th Pursuit Squadron under the command of Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker, and the 27th Pursuit Squadron, which had "balloon buster" 1st Lt. Frank Luke as one of its pilots, achieved distinguished records in combat and remained a permanent part of the air forces.

Observation planes often operated individually, as did pursuit pilots to attack a balloon or to meet the enemy in a dogfight. However the tendency was toward formation flying, for pursuit as well as for bombardment operations, as a defensive tactic. The dispersal of squadrons among the army ground units (each corps and division had an observation squadron attached) made coordination of air activities difficult, so that squadrons were organized by functions into groups, the first of these being the I Corps Observation Group, organized in April 1918 to patrol the Toul Sector between Flirey and Apremont in support of the U.S. 26th Division.[50] On May 5, 1918, the 1st Pursuit Group was formed, and by the armistice the AEF had 14 heavier-than-air groups (7 observation, 5 pursuit, and 2 bombardment).[51] Of these 14 groups, only the 1st Pursuit and 1st Day Bombardment Groups had their lineage continued into the post-war Air Service. In July 1918 the AEF organized its first wing formation, the 1st Pursuit Wing, made up of the 2d Pursuit, 3rd Pursuit, and 1st Day Bombardment Groups.

Each army and corps echelon of the ground forces had a chief of air service designated to direct operations. The Air Service, First Army was activated August 26, 1918, marking the commencement of large scale coordinated U.S. air operations. Foulois was named chief of the First Army Air Service over Mitchell, who had been directing air operations as chief of the I Corps Air Service since March, but Foulois voluntarily relinquished his post to Mitchell and became the Assistant Chief of Air Service, Tours, to unsnarl delays in personnel, supply, and training. Mitchell went on to become a brigadier general and chief of the Army Group Air Service in mid-October 1918, succeeded at First Army by Col. Thomas Milling. The Air Service, Second Army was activated on October 12 with Col. Frank P. Lahm as chief but was not ready for operations until just before the armistice. The Air Service, Third Army was created immediately after the armistice to provide aviation support to the army of occupation, primarily from veteran units transferred from the First Army Air Service.

Despite their fractious relationship, Mitchell and Foulois were of one mind on the necessity of forming an "air force" to centralize control over tactical aviation. In the St-Mihiel Offensive, commencing September 12, 1918, the American and French offensive against the German salient was supported by 1,481 airplanes directed by Mitchell, totaling 24 Air Service, 58 French Aéronautique Militaire, and three Royal Air Force squadrons in coordinated operations. Observation and pursuit planes supported ground forces, while the other two-thirds of the aerial force bombed and strafed behind enemy lines. Later, during the Meuse-Argonne offensive, Mitchell employed a smaller concentration of airpower, nearly all American this time, to keep the German army on the defensive.

Army of occupation duties

Promptly after the armistice, the AEF formed the Third United States Army to march immediately into Germany, occupy the Coblenz area, and be prepared to resume combat if peace treaty negotiations failed. Three corps were formed from eight of the Army's most experienced divisions,[n 22] and Mitchell was appointed Chief of Air Service, Third Army, on November 14, 1918.[52]

As with the ground forces, the most veteran units of the Air Service were selected to form the new Air Service. A pursuit unit, the 94th "Hat in the Ring" Aero Squadron; a day bombardment squadron, the 166th; and four observation squadrons (1st, 12th, 88th, and 9th Night) were initially assigned.[53] The demobilization of the AEF accelerated in December and January, and all but two of these squadrons returned to the United States. Mitchell was replaced in January as commander of the Third Army Air Service by Col. Harold Fowler, a combat veteran of the Royal Flying Corps and former commander of the American 17th Pursuit Squadron.

On April 15, 1919, the Second Army Air Service in France also closed down. Its former air units were transferred to the Third Army Air Service in Germany. The Third Army and its air service were inactivated in July 1919 after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.[54]

Chiefs, AEF Aviation

Aviation Officer, AEF

- Major Townsend F. Dodd, June 13, 1917

Chiefs of Air Service, AEF

- Lt. Col. William L. Mitchell, June 30, 1917

- Brig. Gen. William L. Kenly, September 3, 1917

- Brig. Gen. Benjamin D. Foulois, November 27, 1917

- Maj. Gen. Mason Patrick, May 29, 1918

Statistical summary, World War I

"Though the casualties in the air force were small compared with the total strength, the casualty rate of the flying personnel at the front was somewhat above the Artillery and Infantry rates... The results of allied and American experience at the front indicate that two aviators lose their lives in accidents for each aviator killed in battle." —Report of the Secretary of War, 1919[49]

The Air Service, American Expeditionary Force, totaled 78,507 personnel (7,738 officers and 70,769 enlisted men) at the armistice. Of this total, 58,090 served in France; 20,075 in England; and 342 in Italy. Balloon troops made up approximately 17,000 of the Air Service, with 6,811 in France, conducting and supporting the dangerous duty of spotting for the artillery at the front.[32][55] In all, 211 squadrons of all types trained in Great Britain, with 71 arriving in France before the Armistice.[56] At its peak establishment in November 1918, the Air Service was based at 31 stations in the Services of Supply (rear areas) and 78 aerodromes in the Zone of Advance (combat area).[57][n 23]

The 740 combat airplanes[58][n 24] equipping the units at the front on November 11, 1918, were approximately 11% of the total combat aircraft strength of the Allied forces.[59][n 25] The 45 squadrons in the Zone of Advance had 767 pilots, 481 observers, and 23 aerial gunners, covering 137 kilometers of front from Pont-à-Mousson to Sedan. They flew more than 35,000 hours over the front lines.[60] The Air Service conducted 150 bombing missions, the longest 160 miles behind German lines, and dropped 138 tons (125 kg) of bombs. Its squadrons had confirmed destruction of 756 German aircraft and 76 German balloons, creating 71 Air Service aces. Rickenbacker finished the war as the leading American ace, with 26 aircraft destroyed.[61][n 26] 35 balloon companies also deployed in France, 17 at the front and six en route to the Second Army, and made 1,642 combat ascensions totaling 3,111 hours of observation.[62] 13 photographic sections were assigned to observation squadrons and made 18,000 aerial photographs.[60]

43 flying training, air park (supply), depot (maintenance), and construction squadrons were located in the Services of Supply.[59] A major air depot at Colombey-les-Belles;[n 27] three other maintenance depots at Behonne, LaTrecey, and Vinets; four supply depots at Clichy, Romorantin, Tours, and Is-sur-Tille; and 12 air park squadrons maintained the combat and training forces.[63] Aircraft acquired from European sources were accepted at Aircraft Acceptance Park No. 1 at Orly, while those shipped from the United States for assembly in France were delivered to Air Service Production Center No. 2, built on the site of a former pine forest at Romorantin.[64] Ferry operations of over 6,300 new aircraft to the air depots in "often...far from perfect" weather conditions resulted in the successful delivery of 95% and the loss of only eight pilots.[63]

A large training establishment was also set up.[n 28] In France the Air Service Concentration Barracks at Saint-Maixent received all newly arrived Air Service troops, distributing them to 26 training fields and schools throughout the central and western regions of the country.[65] Flying training schools, equipped with 2,948 airplanes, supplied 1,674 fully trained pilots and 851 observers to the Air Service, with 1,402 pilots and 769 observers serving at the front. The observers trained in France included 825 artillery officers from the infantry divisions who volunteered to fill a critical shortage in 1918.[66] After the Armistice, the schools graduated 675 additional pilots and 357 observers to serve with the Third Army Air Service in the Army of Occupation.[67] The 3rd Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun provided 766 pursuit pilots.[68] 169 students and 49 instructors died in training accidents.[69] Balloon candidates made 4,224 practice ascensions while training.

Air Service combat losses were 289 airplanes and 48 balloons[48][70][n 29] with 235 airmen killed in action,[n 30] 130 wounded, 145 captured, and 654 Air Service members of all ranks dead of illness or accidents.[71] Air Service personnel were awarded 611 decorations in combat, including 4 Medals of Honor and 312 Distinguished Service Crosses (54 were oak leaf clusters).[n 31] 210 decorations were awarded to aviators by France, 22 by Great Britain, and 69 by other nations.[72]

Post-war

Consolidation of the Air Service

Executive Order 3066, issued by President Wilson on March 19, 1919, formally consolidated the BAP and DMA into the Air Service, United States Army.[73][n 32] Anticipating the order, Director of Air Service Maj. Gen. Charles Menoher undertook a sweeping re-organization on March 15, using the "divisional system" of the AEF as a model.[2] Menoher created an advisory board representing the key branches of the Army, and appointed an Executive to coordinate policy between four groups, each headed by an Assistant Executive: Supply, Information, Training and Operations, and Administrative.[74][75] With the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919, President Wilson relinquished his war powers under the Overman Act, and on July 11 Congress granted legislative authority to continue the Air Service as a temporary independent branch of the War Department for another year, easing fears of airmen that the Air Service would be demobilized out of existence.[76][n 33]

At the end of November 1918, the Air Service consisted of 185 flying, 44 construction, 114 supply, 11 replacement, and 150 spruce production squadrons; 86 balloon companies; six balloon group headquarters; 15 construction companies; 55 photographic sections; and a few miscellaneous units. Its personnel strength was 19,189 officers and 178,149 enlisted men.[77] Its aircraft inventory consisted primarily of Curtiss JN-4 trainers, de Havilland DH-4B scout planes, SE-5 and Spad S.XIII fighters, and Martin MB-1 bombers.[78]

Complete demobilization of the Air Service was accomplished within a year. By November 22, 1919, the Air Service had been reduced to one construction, one replacement, and 22 flying squadrons; 32 balloon companies; 15 photographic sections; and 1,168 officers and 8,428 enlisted men.[77] The combat strength of the Air Service was only four pursuit and four bombardment squadrons. Although the leaders of the reorganized Air Service persuaded the General Staff to increase the combat strength to 20 squadrons by 1923, the balloon force was demobilized, including dirigibles, and personnel shrank even further, to just 880 officers. By July 1924, the Air Service inventory was 457 observation planes, 55 bombers, 78 pursuit planes, and 8 attack aircraft, with trainers to make the total number 754.[78]

The Air Service replaced its wartime structure with the formation of six permanent groups in 1919, four of which were based in the United States and two overseas. The first of the new groups, the Army Surveillance Group, was organized in July to direct the operations of three squadrons[n 34] patrolling the border with Mexico, where revolution had broken out, from Brownsville, Texas to Nogales, Arizona. In addition, the 1st Day Bombardment Group was formed to control four bombardment squadrons at Kelly,[n 35] while the 1st Pursuit Group of four pursuit squadrons[n 36] relocated from Selfridge Field, Michigan, to add their weight to the effort. Collectively the three groups (the entire combat strength of the Air Service in the continental United States) comprised the 1st Wing. In January 1920 only the surveillance group continued the patrols, which gradually diminished until June 1921 when they ceased entirely.[79][n 37]

Another group was organized overseas in 1920 to administrate squadrons in the Philippines. In 1921, the three groups based within the United States were sequentially numbered one through three and assigned different combat roles. The fourth was inactivated. The next year the groups overseas were numbered four through six as "composite" groups. In 1922 plans were formulated for three more groups to flesh out the anticipated GHQ Air Force, but only one, the 9th Observation, was formed. The 7th Bombardment and 8th Fighter Groups were designated but not activated until the end of the decade.

National Defense Act of 1920

Sect. 13a. There is hereby created an Air Service. The Air Service shall consist of one Chief of Air Service with the rank of major-general, one assistant with the rank of brigadier-general, 1,514 officers in grades from colonel to second lieutenant, inclusive, and 16,000 enlisted men, including not to exceed 2,500 flying cadets... — Section 13a, Public Law 242, 41 Stat. 759[80]

With the passage of the National Defense Act, June 4, 1920 (Public Law 66-242, 41 Stat. 759-88),[n 38] the Air Service was statutorily recognized as a combatant arm of the line along with the Infantry, Cavalry, Field Artillery, Coast Artillery, Corps of Engineers, and Signal Corps, and given a permanent organization with a fixed complement of personnel. However this also legislated the form of the Air Service to that desired by the General Staff to maintain the aviation arm as an auxiliary component controlled by ground commanders in furtherance of the mission of the infantry.

A Chief of Air Service was authorized with the rank of major general to replace the previous Director of Air Service, and an assistant chief created in the rank of brigadier general (from 1920 to 1925 this position was held by Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell). The primary missions of the Air Service were observation and pursuit aviation, and its tactical squadrons in the United States were controlled by the commanders of nine corps areas and three overseas departments created by the Act, primarily in support of the ground forces. The Chief of the Air Service retained command of training schools, depots, and support activities exempted from corps area control. The headquarters of the Air Service was housed in the Munitions Building in Washington, D.C. and consisted of an executive staff including the chiefs of the Finance and Medical Sections, and four divisions, each administered by a chief: Personnel Group, Information Group (Intelligence), Training and War Plans Group, and Supply Group.[n 39]

The Air Service of 1925 numbered five airship companies, an airship service company, 32 tactical squadrons (eight pursuit, eight bombardment, two attack, and 14 observation), six school squadrons,[n 40] and 11 service squadrons. Half of the pursuit and bombardment squadrons and three each of the observation and service squadrons were based outside the continental United States.[81]

The General Staff produced a mobilization plan that in the event of war would create a field force of six armies, 18 corps, and 54 divisions. Each army would have an Air Service attack wing (one attack and two pursuit groups) and an observation group, each corps and division would have an observation squadron, and a seventh attack wing-observation group would be reserved for the Expeditionary Force's general headquarters. A single bombardment group was planned, relegating bombardment to the most minor of roles. All aviation units would be under the command of ground officers at all levels. While promoting unity of command within the service as its most important principle, the plan obviated concentration of forces by its air units. This structure provided the principles by which the Air Service and Air Corps operated until 1935.

The principal pursuit planes of the Air Service were the MB-3 (50 in inventory), the MB-3A (200 acquired 1920–23), and the Curtiss PW-8/P-1 Hawk (48 acquired in 1924–25). The only bomber ordered in quantity was the Martin NBS-1 (130 ordered 1920–1922), the mass-produced version of the MB-2 bomber developed in 1920. Mitchell used the NBS-1 as the primary striking weapon during his demonstration in July 1921 off the Virginia coast that resulted in the sinking of the captured German battleship Ostfriesland.

Aeronautical development became the responsibility of the Technical Section, Air Service, created January 1, 1919, consolidating the Aircraft Engineering Department BAP, the Technical Section DMA, and the Testing Squadron at Wilbur Wright Field, which was renamed the Engineering Division on March 19 and relocated to McCook Field, Dayton, Ohio.

A formal training establishment was also created by the Air Service on February 25, 1920, when the War Department authorized the establishment of service schools. Flying training, originally at Carlstrom Field in Florida and March Field in California, moved to Texas, divided between the 11th School Group (primary flying training) at Brooks Field and the 10th School Group (advanced flying training) at Kelly Field. A technical school for mechanics was located at Chanute Field, Illinois. The Air Service Tactical School was set up at Langley Field, Virginia, to train officers for higher command and to instruct in doctrine and the employment of military aviation. The Engineering Division created an air engineering school at McCook Field and moved it to Wright Field when that base was established in 1924.[82][n 41]

Groups of the Air Service

| Original Designation | Station | Date created | Redesignation (date) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Army Surveillance Group | Fort Bliss, Texas | July 1, 1919 | 3d Group (Attack)² (1921) |

| 2nd Observation Group | Luke Field, Hawaii | August 15, 1919 | 5th Group (Composite)² (1922) |

| 1st Pursuit Group | Selfridge Field, Michigan | August 22, 1919 | 1st Group (Pursuit)² (1921) |

| 1st Day Bombardment Group | Kelly Field, Texas | September 18, 1919 | 2d Group (Bombardment)² (1921) |

| 3d Observation Group | France Field, Panama | September 30, 1919 | 6th Group (Observation)² (1922) |

| First Army Observation Group | Langley Field, Virginia | October 1, 1919 | 7th Group (Observation) (1921)¹ |

| 1st Observation Group | Ft. Stotsenburg, Luzon | March 3, 1920 | 4th Group (Composite)² (1922) |

| 9th Group (Observation)² | Mitchel Field, New York | August 1, 1922 |

- ¹Inactivated (1921), redesignated Bombardment while inactive (1923), re-activated 1928

- ²Original 7 groups of US Army Air Corps

Annual Air Service strength

| Year | Strength | Year | Strength | Year | Strength | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918 | 138,997 | 1921 | 11,830 | 1924 | 10,488 | ||

| 1919 | 24,115 | 1922 | 9,888 | 1925 | 9,719 | ||

| 1920 | 9,358 | 1923 | 9,407 | 1926 | 9,578 |

Heads of the Air Service

Directors of Air Service

- John D. Ryan (August 28, 1918 – November 27, 1918)

- Maj. Gen. Charles T. Menoher (January 2, 1919 – June 4, 1920)

Chiefs of Air Service

- Maj. Gen. Charles T. Menoher (June 4, 1920 – October 4, 1921)

- Maj. Gen. Mason M. Patrick (October 5, 1921 – July 2, 1926)

Debate over an independent Air Force

Framing the issues

The seven-year history of the post-war Air Service was essentially a prolonged debate between adherents of airpower and the supporters of the traditional military services about the value of an independent Air Force, spurred by the creation of the Royal Air Force in 1918. On one side were Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell, Brig. Gen. Benjamin Foulois, a cadre of young former Reserve officers who made up the overwhelming majority of Army pilots, and a few like-minded politicians and newspapers. Opposed were the General Staff of the Army, its senior leadership from World War I, and the Navy.[83] The doctrinal differences were both defined and intensified by struggles for funds caused by the skimpy budgets authorized for the War Department, first by the penurious policies of the Republican administrations in the 1920s, and then by the fiscal realities of the Great Depression. In the end, the struggle for funds as much as any other factor caused the impetus for an independent Air Force.[84]

While this debate focused largely on the controversial Mitchell, its early star was Foulois. Both returned from France with combat leadership experience in aviation, expecting to become the peacetime leaders of the Air Service. Instead, the War Department appointed Maj. Gen. Charles Menoher, who had commanded the Rainbow Division in France, to be Director of the Air Service to replace Secretary Ryan, signaling to the nation and the airpower proponents its intent to keep the air arm under the direction of the ground forces.[85] Foulois was reduced to his permanent establishment rank of captain and assigned to head a minor agency. Mitchell received the vacant position of Director of Military Aeronautics, but its responsibilities had been transferred to Menoher by Executive Order 3066 to end the dual status mess of the DMA and BAP, and his position was titular only. Instead he became Third Assistant Executive (in effect, S-3), chief of the new Training and Operations Group, where he installed like-minded airmen who had served with him France as division heads and used the position to expound his theories.[86][n 42]

In 1919, Mitchell proposed a Cabinet-level Department of Aviation equal to the War and Navy Departments to control all aviation, including sea-based air, airmail, and commercial operations. His goal was not only independent and centralized control of airpower, but also encouragement of the peacetime U.S. aviation industry. Mitchell insisted that the debate be both "broad and civil". Foulois, however, complained bitterly to the United States Congress about the historical neglect and indifference of the Army to its air service.[87][n 43] Although two bills to create Mitchell's proposed department were introduced, in the Senate by Sen. Harry S. New of Indiana and in the House by Rep. Charles F. Curry of California, and initially garnered strong support, the opposition of the Army's wartime leaders (especially General Pershing) frustrated the effort at the start.[n 44] In August 1919 Gen. Menoher was assigned to chair a board consisting of himself and three other generals, all artillery officers and former infantry division commanders, appointed to report back to Congress on the proposed legislation. In October it predictably argued that unity of command and conformity to Army discipline overrode all other considerations.[88] Support for the New and Curry bills evaporated and resulted in the passage of the less radical National Defense Act of 1920 conforming to the desires of the General Staff.[85]

Mitchell was not discouraged by the failure of his first proposal. He recognized the value of public opinion in the debate and changed tactics, embarking on a publicity campaign on behalf of military aviation. General Menoher, when he was unable to persuade Secretary of War John Wingate Weeks to silence Mitchell, resigned his position on October 4, 1921, and was replaced by Maj.Gen. Mason Patrick. Although an engineer and not an aviator, Patrick had been Pershing's Chief of Air Service in France, where his primary duty had been to coordinate the activities of Foulois and Mitchell, then rivals. Patrick had also testified before Congress against Mitchell's plan for an independent air force.[89]

Patrick was not hostile to aviation, however. He underwent flight training and obtained his wings, then issued a series of reports to the War Department emphasizing the need to expand and modernize the Air Service. In his first annual report in 1922, he warned that the Air Service had been degraded by budget cuts to the degree that it could no longer meet its peacetime obligations, much less mobilize for war. In one of the Air Service's first inclusions in the army's promotion system after becoming a combatant arm, among the 669 lieutenant colonels on the 1922 candidate list for colonel, the first Air Service member (James E. Fechet) was 354th. Patrick supported and issued the first air doctrine for the service, Fundamental Conceptions (patterned on Army Training Regulation 10-5 Doctrines Principles and Methods), which outlined strategy and tactics for the air arm.[90][n 45] Patrick was also critical of the policy that placed air units under the command of corps commanders and proposed that only observation squadrons should be part of the ground forces, with all combat forces centralized under the control of an air force attached to General Headquarters.[91][92][n 46]

Investigating committees and boards

The response to the proposal was three boards and committees. The Secretary of War convened the Lassiter Board in 1923, composed of general staff officers who fully endorsed Patrick's views, and adopted the policy in regulations.[93][n 47] The War Department acknowledged the necessity of improving its Air Service and desired to implement the Lassiter Board's recommendations, which it termed "Major Project No. 4", but the Coolidge administration proved a major obstacle, choosing to economize by radically cutting military budgets, particularly the Army's.[94][n 48] Patrick's proposal that appropriations for the Air Service be coordinated with the larger budget of Naval aviation (in effect, shared), was rejected by the Navy, and the reorganization could not be implemented.[95]

The U.S. House of Representatives then appointed the Lampert Committee[n 49] in October 1924 to investigate Patrick's criticisms. Mitchell testified before the committee and, upset by the failure of the War Department to even negotiate with the Navy in order to save the reforms of the Lassiter Board, harshly criticized Army leadership and attacked other witnesses. He had already antagonized the flag and general officers of both services with speeches and articles delivered in 1923 and 1924, and the Army refused to retain him as Assistant Chief of the Air Service when his term expired in March 1925. He was reduced in rank to colonel by Secretary Weeks and exiled to the Eighth Corps Area in San Antonio as air officer, where his continuing, reckless, and increasingly strident criticisms prompted President Calvin Coolidge to order his court-martial. Mitchell's conviction on December 17, 1925, followed by three days the Lampert Committee's recommendations for creation of a unified air force independent of the Army and Navy; creation of "assistant secretaries for air" in the War, Navy, and Commerce Departments; and establishment of a Department of National Defense.[96]

The third board was the Morrow Board, a "blue ribbon" panel convened by President Coolidge in September 1925 to make a general inquiry into U.S. aviation. Headed by an investment banker and personal friend of Coolidge's, Dwight Morrow, the board was made up of a federal judge, the head of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, former military officers now in industry, and the wartime head of the Board of Aircraft Production. The actual purpose of the Morrow Board was to minimize the political impact of the Mitchell trial, and Coolidge directed that it issue its findings by the end of November, to pre-empt the findings of not only the military court but also of the Lampert Committee that might be contrary to the Morrow Board. Its report was released on December 3. The major result of the Morrow Board was to maintain the status quo. It also made the recommendation, adopted in 1926, that the Air Service be renamed the Air Corps, but in doing so Congress denied it the autonomy enjoyed by the Marine Corps within the Navy Department, and thus the change was only cosmetic and the Air Corps remained as an auxiliary arm to the ground forces.[97]

Advances in aviation

To positively influence U.S. public opinion and thereby enlist political support in Congress in his crusade for an independent air force, General Mitchell conducted a publicity campaign on behalf of airpower. On August 14, 1919, the All American Pathfinders, a provisional squadron, began a cross-country educational tour that supported the "1919 Air Service Transcontinental Recruiting Convoy"[98] from Hazelhurst Field to California.[99] While using public pronouncements for propaganda purposes, Mitchell also fostered within the Air Service advances in aeronautical science that would not only increase its effectiveness as a military service, but would also generate public support.

To further promote the air service, and to recruit pilots, in 1919 General Mitchell ordered a mission to fly around the border of the continental United States. Commanded by Col. Rutherford Hartz, and piloted by Lt. Ernest Emery Harmon, "The Around The Rim Flight" took off from Bolling Field in Washington, DC on July 24, 1919. The crew of five also included Lotha Smith, Jack Harding, and Gerosala Dobias. The first circumnavigation of the country by air was successfully completed with the landing of their Martin MB1 back at Bolling Field on Nov 9, 1919.

Mitchell's first project, undertaken at McCook Field, in Dayton, Ohio, was for the creation of a heavily armored attack plane for supporting ground forces. Although the designs that resulted were not practical and did not meet Mitchell's specifications for aircraft that could land troops behind enemy lines, the project led Mitchell to closely supervise aircraft development, not only at McCook but in Europe as well. On October 30, 1919, the McCook Field engineers tested the first reversible-pitch propeller.

This effort resulted in the development of a monoplane with retractable landing gear, a metal propeller, and a streamlined engine design, the Verville R-3 Racer. Economy measures by the Air Service prevented the project from being fully completed, but contributed to a growing determination within the Air Service to set new aviation records for speed, altitude, distance, and endurance, which in turn contributed not only to technical improvements (and favorable publicity) but also advancements in aviation medicine.

Air Service pilots established world records in altitude, distance, and speed. Speed in particular attracted public attention and, although a number of speed records were set in cross-country flying, records were also set on measured courses. Mitchell himself set a world speed record of 222.97 mph (358.84 km/h) over a closed course in a Curtiss R-6 racer on October 18, 1922, at the Pulitzer Trophy competition of the 1922 National Air Races. A later world speed record of 232 mph (373 km/h) was made by 1st Lt. James H. Doolittle in winning the Schneider Trophy race at the 1925 Races.

The practical and military applications of speed were not ignored, however. On February 24, 1921, 1st Lt. William D. Coney of the 91st Aero Squadron completed a transcontinental flight of 22.5 hours flying time from Rockwell Field, California, to Pablo Beach, Florida, in a DeHavilland DH-4, which carried enough fuel for 14 hours of flight. However he had left Rockwell on February 21 intending to complete the flight within 24 hours, making just one stop in Dallas, Texas, but was thwarted by bad weather and engine problems. One month later, taking off at 1:00 a.m. of March 25, he repeated the attempt going in the opposite direction, but developed engine problems while flying low in a fog near Crowville, Louisiana, southeast of Monroe. He crashed into a tree trying to land and was severely injured, dying five days later in a Natchez, Mississippi hospital.[100]

On September 4, 1922, Doolittle completed the first transcontinental crossing in a single day, from Pablo Beach to Rockwell Field, in 21 hours, 20 minutes, a distance of 2,163 mi (3,481 km) flying a DH-4 of the 90th Squadron.[101] Mitchell concluded that accomplishing the same feat by "daylight only", making only a single stop at Kelly Field, had tremendous value, and staged a dawn-to-dusk transcontinental flight across the United States in the summer of 1924 in a Curtiss Curtiss PW-8 fighter developed from the R-6 for that purpose.

Despite the emphasis in the press on speed, the Air Service also established a number of altitude, distance, and endurance records. The Packard-Le Peré LUSAC-11 biplane set world altitude records over McCook Field of 33,114 ft (10,093 m) on February 27, 1920, by Maj. Rudolph W. Schroeder;[n 50] and 34,507 ft (10,518 m) on September 28, 1921, by Lt. John A. Macready. A distance record was set by Capt. St. Clair Streett leading a flight of four DH-4s from Mitchel Field, New York to Nome, Alaska and back, a distance of 8,690 miles (14,000 km), between July 15 and October 20, 1920. Flying across the northern United States and southern Canada in 15 legs, the flight reached Nome on August 23 in 56 hours of flying time, but was prohibited by the U.S. State Department from completing the first flight to Asia across the Bering Strait. The first nonstop endurance flight across the U.S., made in 26 hours and 50 minutes at an average speed of 98.76 mph, was made May 2–3, 1923, from Roosevelt Field, New York, to Rockwell Field in a Fokker T-2 transport monoplane by Macready and Lt. Oakley G. Kelly. The feat was followed in August by a flight in which a DH-4 stayed aloft for more than 37 hours by means of aerial refueling. The Fokker T-2 is on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

The greatest achievement of these projects, however, was the first flight around the world. The Air Service set up support facilities along the proposed route and in April 1924 sent a flight of four aircraft west from Seattle, Washington. Six months later, two aircraft completed the flight. Even if considered as primarily a publicity stunt, the flight was a brilliant accomplishment in which five nations had already failed.

Kelly and Macready, Doolittle, and the crews of the circumnavigation flight all won the Mackay Trophy for the respective years in which they accomplished their feats.

Notable members of the Air Service

- Henry Harley Arnold, aviation pioneer; Commanding General of the U. S. Army Air Forces

- Hobey Baker, star athlete at Princeton University

- David Lewis Behncke, founder and first president of the Air Line Pilots Association

- Hiram Bingham III, United States Senator from Connecticut

- Clayton Bissell, World War I ace, commander of Tenth Air Force during World War II

- Erwin R. Bleckley, artillery officer and Medal of Honor recipient

- Raynal Bolling, general counsel for US Steel; first high-ranking casualty of World War I

- Arthur Raymond Brooks, World War I ace

- Dick Calkins, comic strip artist

- Douglas Campbell, first American ace

- Clarence Chamberlain, aviation pioneer

- Merian C. Cooper, adventurer and Hollywood film producer

- Stephen W. Cunningham, UCLA graduate manager and Los Angeles City Council member

- John F. Curry, Chief of the Civil Air Patrol

- Jimmy Doolittle, air racer, aeronautical engineer, leader of Doolittle Raid

- Etienne Dormoy, pilot and aircraft designer, chief engineer at Buhl Aircraft Company

- Lee Duncan, animal trainer and owner of Rin Tin Tin

- Ira Eaker, commander of U.S. Eighth Air Force during World War II

- Fred Dow Fagg, Jr., law professor and president of the University of Southern California

- Reuben Hollis Fleet, organizer of the first airmail service and founder of Consolidated Aircraft

- Benjamin Delahauf Foulois, aviation pioneer

- Harold Ernest Goettler, Medal of Honor recipient

- Edgar Staley Gorrell, strategic bombing pioneer, president Stutz Motor Company, first president Air Transport Association of America

- Dick Grace, Hollywood stunt flyer

- James Norman Hall, writer, co-author of Mutiny on the Bounty

- Charles W. "Chic" Harley, All-American college football player

- Ernest Emery Harmon, pilot of The Around The Rim Flight 1919

- Arthur Harvey, oil pioneer, author

- Howard Hawks, film director

- Frank Monroe Hawks, barnstormer and aviation records-setter

- Field Kindley, World War I ace

- Fiorello LaGuardia, U.S. Representative and Mayor of New York

- Reed Gresham Landis, ace while flying with Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and early airline executive

- Frederick Libby, first U.S. born ace, while flying with the RFC

- Charles Lindbergh, aviation pioneer; first trans-Atlantic solo pilot

- Raoul Lufbery, member of Lafayette Escadrille and air tactics pioneer

- Frank Luke, ace and Medal of Honor recipient

- Norman Z. McLeod, Hollywood director

- James Ely Miller, first U.S. military aviator killed in action

- Thomas DeWitt Milling, aviation pioneer and first certified U.S. military pilot

- John Purroy Mitchel, mayor of New York City and advocate of universal military training

- Billy Mitchell, airpower visionary

- Odas Moon, pioneer in aerial refueling and bombing doctrine

- Charles Nordhoff, co-author of Mutiny on the Bounty

- Ralph Ambrose O'Neill, WWI flying ace, General of Mexican Air Force, commercial pioneer

- Clyde Pangborn, aviation pioneer, first non-stop flight across the Pacific Ocean

- Leonard J. Povey, barnstormer and inventor of the Cuban Eight maneuver

- LeRoy Prinz – Hollywood choreographer

- Eddie Rickenbacker, highest ranking U.S. ace of World War I and Medal of Honor recipient

- Quentin Roosevelt, youngest son of President Theodore Roosevelt

- John Monk Saunders, author and screenwriter

- Lowell Smith pioneer test pilot, who led the first aerial circumnavigation (1924)

- Carl Andrew Spaatz, first Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force

- Albert Spalding, classical violinist

- Delmar T. Spivey, gunnery expert, and highest ranking USAAF officer shot down and made P.O.W. in the ETO

- Elliott White Springs, ace with RFC and USAS, post-war pulp fiction writer

- George E. Stratemeyer, USAF General

- Stephen W. Thompson, first U. S. military aerial victor

- George Augustus Vaughn, Jr., World War I Ace

- Alfred V. Verville, aircraft designer of two Pulitzer Trophy winning aircraft, the Verville-Packard R-1 Racer and the Verville-Sperry R-3 Racer

- Eugene Luther Vidal, Olympic athlete, commercial aviation pioneer, and New Deal official

- William Wellman, Hollywood film director

- Charles A. Willoughby, World War II general in the United States Army

- Albert J. Winegar, Wisconsin State Assemblyman

- John Gilbert Winant, educator, governor of New Hampshire, and ambassador to Britain

Lineage of the United States Air Force

- Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps August 1, 1907 – July 18, 1914

- Aviation Section, Signal Corps July 18, 1914 – May 20, 1918

- Division of Military Aeronautics May 20, 1918 – May 24, 1918

- Air Service, United States Army May 24, 1918 – July 2, 1926

- United States Army Air Corps July 2, 1926 – June 20, 1941

- United States Army Air Forces June 20, 1941 – September 18, 1947

- United States Air Force September 18, 1947–present

See also

- List of Air Service American Expeditionary Force aerodromes in France

- List of American Aero Squadrons

- List of American Balloon Squadrons

- Organization of the Air Service of the American Expeditionary Force

- Organization of the U.S. Army Air Service in 1925

- Philippine Scouts

- United States Army World War I Flight Training

References

- Footnotes

- The airplane figure is variously given as 250 (A History of the United States Air Force, 1907–1957, Alfred Goldberg, editor; USAF Historical Study 138) to 280 by Hennessy. In any case, the Aviation Section had more than twice as many aircraft as pilots to fly them.

- Approximately $14 billion in 2015 dollars. US Inflation Calculator

- The overwhelming bulk of the appropriation, $525M, was allotted for equipment including 22,600 aircraft, with the next highest amount, $41M, for construction. Training received only $1M. The figures had been hastily assembled as a response to a telegram to President Wilson from French premier Alexandre Ribot at the end of May urging the U.S. to contribute 4,500 aircraft; 5,000 pilots; and 50,000 mechanics to the war effort.

- Nearly all of Ryan's time between his appointment and the armistice was spent in Europe familiarizing himself with the Air Service. (Holley, p. 69)

- All cadets were enlisted into the Signal Corps or Reserve Signal Corps in the rank of private first class only for the duration of pilot training. Those that washed out were discharged and subject to the draft.

- The initial six were the University of California, Cornell, Illinois, MIT, Ohio State, and Texas. Princeton and Georgia Tech were added shortly after.

- Bingham's memoir An Explorer in the Air Service stated that the number of graduates in the first class was 132.

- The course of study could not "be predetermined as to length", dependent "in large measure on the weather, the supply of 'spares', and a man's own ability". Air Service Journal, September 27, 1917, Vol. I, No. 12, p. 370.

- Bingham (1920), p. 80, gives the number as 1,800, but a table in Gorrell's History itemizes the total number sent overseas as 1,710, of which 300 were diverted in England, so his figure likely includes those who did receive their training. Bingham stated that the cadets sent to France had been Honor Graduates of the ground course. The failure of the French to train these best candidates came as a bitter disappointment to the Air Service and was extremely detrimental to their morale.

- 999 were commissioned in France, 406 in Italy, and 204 in Britain. In addition, 178 graduated from RAF schools in Canada, and 975 graduated from schools in France between the armistice and January 1919.

- The five "schools of military aeronautics" still operating at the armistice were at Cornell, Princeton, Texas, Cal, and Illinois.

- The situation at Air Service headquarters was described as "a tangled mess" before Patrick brought order. Pershing acknowledges that Foulois requested relief before he was replaced, but the request came only after Foulois became aware of the severity of Pershing's displeasure and attempts in April to rein in his own staff had failed.

- Pershing requested 125 balloon companies, and the United States manufactured nearly a thousand Caquot balloons in 1918–1919.

- The U.S. roundel had the same color order as that of the Imperial Russian Air Service but in diameters of equal proportion.

- The first two squadrons so authorized were the 1st and 103rd Aero Squadrons in recognition of their prior service in Mexico and France, respectively.

- Miller had assumed command of the 95th upon its arrival at its first station at the front, Villeneuve-les-Vertus, on February 20. The squadron had just received its Nieuport 28 aircraft but without guns mounted. To gain experience, Miller accompanied two other American officers on a voluntary patrol over the lines in SPADs borrowed from the French. They encountered a German patrol and Miller was killed when his German opponent gained the advantage on him. He was two weeks short of his 35th birthday.

- Baer was also the first Air Service ace, not Campbell, his achievements preceding each of Campbell's by more than a month, fully credited by the USAF Historical Research Agency (AFHRA). The omission of these from so many accounts is almost certainly due to the attachment of the 103rd to French units until July 1918, of which observers such as Lahm were unaware at the time.

- Until June 1918, designated Company B, 2nd Balloon Squadron. The 2nd Balloon Company is now the 2d Special Operations Squadron (AFRC), an MQ-9 Reaper UAV unit. 2 SOS fact sheet Archived 2011-09-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Each pursuit squadron was authorized 25 aircraft, including seven reserve spares, and 18 pilots.

- Observation squadrons had 24 airplanes including 6 spares, 18 pilots, and 18 observers.

- Day bombardment squadrons had 25 aircraft including spares, and 18 pilots. Night bombardment squadrons had 14 aircraft including spares, 10 pilots, and 10 observers.

- The 1st, 2nd, and 32nd Divisions formed the III Corps; the 3rd, 4th, and 42nd Divisions the IV Corps; and the 89th and 90th Divisions the VII Corps. Five other divisions (5th, 7th, 28th, 33rd, and 79th) guarded the line of communications through Belgium and Luxembourg.

- In contrast, the United States Navy operated ten anti-submarine/convoy patrol stations in France, five in Ireland, one in England, and four bombing bases: three in France and one in Italy. Four of the bases operated balloons and dirigibles. In addition it had reception bases in France and England, and training bases in France and Italy.

- Quoting Mitchell, there were 196 American-made, 16 British-made, and 528 French-made aircraft. By function these were 330 pursuit, 293 observation and 117 day bombardment.

- In October 1919 Col. Edgar S. Gorrell appeared before the Frear subcommittee on aviation expenditures and presented a table showing that the Allies had a total of 6,748 combat ("service") aircraft of all types on the day of the armistice. The French had the most (3,321), followed by the British (1,758), the Italians (812) and then the U.S.

- The actual number of American aces is disputed. Gorrell's History reported 118 aces, when the Air Service followed the French practice of crediting each aviator participating in a kill with a whole victory, prompting a review by USAF from 1965–1969 to identify the actual number of aircraft destroyed. A preliminary assessment by the USAF (Historical Study 73) identified 69 Air Service aces using later accounting methods (the British practice of dividing kills into "partial credit" fractions for multiple shooters). Its final product, USAF Historical Study 133, placed the total at 71 aces. The studies did not change the original credits awarded, however, and official credits remain as published in World War I. The review distinguished between 491 kills made by one pilot against one aircraft, and an additional 342 kills that resulted in 1022 partial credits. None of the figures, however, includes kills made by members while they previously served in a foreign air service.

- Colombey-les-Belles was located behind the lines near the front but its excellent camouflage kept it "remarkably free" from air attack. Maurer 1978, Vol. I, p. 119.

- The Air Service AEF established eight Aviation Instruction Centers in Europe: 1st (Paris, aviation mechanics), 2nd (Tours, primary flying), 3rd (Issoudun, advanced flying), 4th (Avord, a liaison detachment to the French air force), 5th (Bron, mechanics, closed soon after being opened), 6th (Pau, French aviation school), 7th (Clermont-Ferrand, bombardment), and 8th (Foggia, Italy; primary flying).

- U.S. balloon losses were 35 destroyed by German fighters, 12 by antiaircraft guns, and 1 that broke its cable and came down behind the lines. Balloons were attacked 89 times, resulting in 125 parachute jumps by balloon observers, but only one death occurred, that of 1st Lt. Cleo J. Ross, 8th Balloon Company. Allowing a new observer to jump first, Ross parachuted on the afternoon of September 26, 1918 when his balloon was set on fire by a Fokker D.VII. The burning balloon descended at twice the rate of the parachute and enveloped Ross, who fell nearly 1000 meters.

- Col. Bolling was the highest-ranked casualty, killed in action in ground combat on March 26, 1918, while on a tour of the Somme battlefield.

- The large number of DSC awards is due to it being the only other combat valor award at the time. The Silver Star was not authorized until 1932 and the Bronze Star until 1944.

- The issue was so important that Wilson took the draft of the order with him to France to attend the Versailles peace conference, and cabled its promulgation to Washington.

- The Aviation Section of the Signal Corps was a statutory entity and would have legally resumed its functions without the action by Congress.

- The squadrons of the Army Surveillance Group were the 8th (McAllen and Laredo, Texas), 90th (Sanderson and Eagle Pass, Texas), and 104th (Fort Bliss and Marfa, Texas) Surveillance Squadrons. In January 1920 the group, now re-designated the 1st Surveillance Group, was joined by the 12th Surveillance Squadron based at Nogales and Douglas, Arizona. Maurer Maurer, Aviation in the U.S. Army, 1919–1939, Appendix 2, USAF Historical Research Center (1987), pp. 455–456.

- The 1st Day Bombardment Group: 11th, 20th, 96th, and 166th Bombardment Squadrons.

- 1st Pursuit Group: 27th, 94th, 95th, and 147th Pursuit Squadrons.

- The surveillance group and all of its surveillance squadrons, flying the DH-4B, were re-designated "attack" in September 1921.

- The National Defense Act of 1920 was a modification of the National Defense Act of 1916. It had its origins in and is often referred to by contemporary writings as the "Army Reorganization Act of May 18, 1920".

- The chiefs of these four divisions correlate to the modern general staff positions G-1, −2, −3, and −4. The Engineering Division remained located at McCook Field, Ohio.

- The school squadrons were created in early 1923.

- Other service schools established were the Pursuit School at Rockwell Field, the Bombardment School at Ellington Field, the Observation School at Henry Post Field, the Balloon School at Lee Hall, Virginia, and the Airship School at Brooks.

- Lt. Col. Oscar Westover, a former infantryman and advocate of submission to "proper authority," was Menoher's deputy executive officer and urged him to relieve Mitchell and his followers if they did not cease their advocacy of an independent air force.

- Foulois and Menoher testified together at subcommittee hearings on the bill, at which time Menoher characterized aviators as "temperamental" and suggested that their enthusiasm for an independent air service was the result of a desire for personal promotion, a theme often repeated by numerous opponents of an independent air force over the next two decades. Foulois, a firebrand who later learned to work within the system, had been reduced in rank from brigadier general to captain by the armistice and was stung by the comments. In a solicited statement following Menoher's, he acidly defied the General Staff to name one instance in which it had done anything constructive towards aviation.

- In all, 12 bills and resolutions for a separate air force/department were proposed in Congress between the end of World War I and June 1920, of which only Sen. New's S. 3348 ever emerged from committee. (Mooney and Layman, p. 53)

- In 1923 Army doctrine was organized into Field Service Regulations, which were general in character, and Training Regulations (TR), which stated combat principles for each combatant arm.

- Under the terminology of the day, in TR 440-15, "air service aviation" denoted an auxiliary force (primarily observation units) supporting the ground forces, while "air force aviation" described a combat force whose primary mission was to gain control of the air, then destroy the most important enemy forces on land or sea. (Futrell, p. 40)

- The policy set forth by Patrick was published in the Tenth Annual Report of NACA.

- The Coolidge administration boasted of cutting the War Department's budget by 75%.

- "The Select Committee of Inquiry into the Operations of the U.S. Air Services", chaired by Rep. Florian Lampert (Republican, Wisconsin).