Victoria Kamāmalu

Victoria Kamāmalu Kaʻahumanu IV (November 1, 1838 – May 29, 1866) was Kuhina Nui of Hawaii and its crown princess. Named Wikolia Kamehamalu Keawenui Kaʻahumanu-a-Kekūanaōʻa[4] and also named Kalehelani Kiheahealani,[4] she was mainly referred to as Victoria Kamāmalu or Kaʻahumanu IV, when addressing her as the Kuhina Nui.

| Victoria Kamāmalu | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crown Princess of the Hawaiian Islands and Kuhina Nui of the Hawaiian Islands | |||||

| |||||

| Kuhina Nui of the Hawaiian Islands | |||||

| Reign | January 16, 1855 – December 21, 1863 | ||||

| Predecessor | Keoni Ana | ||||

| Successor | Kekūanāoʻa | ||||

| Monarch | Kamehameha IV Kamehameha V | ||||

| Born | November 1, 1838 Honolulu Fort, Honolulu, Oʻahu | ||||

| Died | May 29, 1866 (aged 27) Papakanene, Honolulu, Oʻahu | ||||

| Burial | June 30, 1866[1][2][3] Mauna ʻAla Royal Mausoleum | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Kamehameha | ||||

| Father | Kekūanāoʻa | ||||

| Mother | Kīnaʻu | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Family

Born at the Honolulu Fort, on November 1, 1838, she was the only daughter of Elizabeth Kīnaʻu (Kaʻahumanu II) and her third husband Mataio Kekūanāoʻa. Through her mother she was granddaughter of King Kamehameha I, founder of the united Hawaiian Kingdom. Her two brothers would later become kings of Hawaii as Kamehameha IV and Kamehameha V. She was named after her maternal aunt Queen Kamāmalu, the consort of Kamehameha II, who died in London from the measles. The Christian name Victoria was after Queen Victoria and signified the close friendship of the British monarchs and the Hawaiian monarchs.[5][6] Having given away her previous four sons, Kīnaʻu refused to give her only remaining daughter in hānai to John Adams Kuakini who wanted to take her to be raised on the Big Island. Kīnaʻu defied the customs of the time and personally nursed her daughter.[7] Kīnaʻu died from the mumps a few months after Victoria's birth. She would become the highest female chief in Hawaii at the time. Her kahu (attendants) were John Papa ʻĪʻī and his wife Sarai. They later accompanied Victoria to school due to her age.[5][8]

Early life

Victoria was educated at Chiefs' Children's School (later renamed Royal School) along with all her cousins and brothers.[9] Along with her other classmates, she was chosen by Kamehameha III to be eligible for the throne of the Kingdom of Hawaii.[10][11] She was expected from birth to one day succeed to the position of Kuhina Nui if not the office of monarch, so she was educated by the Cookes with full attention to what political roles she might play in the near future. In the school, the students were permitted to visit with relatives from time to time. When the students fell ill, their kahu and families went to the school and stayed for a while to attend to them. Victoria's kahu, John Papa ʻĪʻī, was eventually appointed kahu for all of the students at the Chief's Children's School and visited in that capacity, though his political services were in such demand by the court that he was often absent.

Victoria's father Kekūanāoʻa raised her. He was the royal governor of Oahu. In Honolulu her father built her a Greek-revival mansion which was the largest house in the town of Honolulu, or anywhere in Hawaii, at the time. Her father was in debt to foreigners, however, so Kamehameha III bought the palace from him. He made it his royal palace and called it Hale Aliʻi (House of the Chiefs) and it was the first ʻIolani Palace.

Victoria was two months younger than the future queen Liliʻuokalani. At her birth, the High Chiefess Laura Kōnia went to Kīnaʻu with her adoptive daughter Liliʻu. Kīnaʻu would nurse Liliʻu while handing her own daughter to a nurse. According to Liliʻuokalani, both girls would share everything from a young age and when Victoria visited her aunt Kekāuluohi, Liliʻuokalani would be invited too. Victoria was destined from a young age to become a sovereign like her siblings, but it would be Liliʻuokalani who would later become the first Queen of Hawaii due to Victoria's early death.[12]

Bernice Pauahi Bishop, another classmate at the Royal School, was hānai to Kīnaʻu and Kekūanāoʻa. Originally betrothed to Victoria's brother Lot, Pauahi married American businessman Charles Reed Bishop on May 4, 1850 against the wishes of her biological parents Pākī and Kōnia and Victoria's father. A year later, in August 1851, the twelve year-old Victoria helped reconciled Pauahi with her parents and Kekūanāoʻa.[9][13]

Kuhina Nui

It was intended that Victoria would succeed her mother Kīnaʻu in the position of Kuhina Nui (premier), but her mother died while she was still an infant. Her aunt Kekāuluohi became a place-holder for her niece using the name Kaʻahumanu III, but she died when Victoria was seven. Subsequently her uncle Kamehameha III appointed John Kalaipaihala Young II, also known as Keoni Ana, the son of John Young, as Kuhina Nui.[14][15] Princess Victoria Kamāmalu was appointed as Heiress Presumptive to the title of Kuhina Nui in 1850, to be the successor to Keoni Ana. Since 1845, by legislative act, the office of Kuhina Nui had been joined with that of the Minister of the Interior. Given her young age, it was clear to the King, Privy Council, and Legislative Council that Victoria was not suited to be Minister of the Interior. Therefore, on January 6, 1855, an act was passed to repeal the earlier legislation.[16]

In 1854, her uncle Kamehameha III died and her brother Alexander Liholiho succeeded him as King Kamehameha IV. According to Robert Crichton Wyllie, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and a trusted friend of the royal family, opponents of the new king were planning to overthrow him and place his sister Princess Victoria on the throne instead. However, the conspiracy never culminated in anything.[17] She became Kuhina Nui in 1855 mainly due to her brother's ascension to the throne after the death of her uncle. It is probable that Kamehameha III had meant for Keoni Ana to hold the office until his death; Keoni Ana did retain the role of Minister of the Interior. Victoria presided over the King's Privy Council.

In 1862, Victoria and her brother Lot were officially added to the line of succession in an amendment to the 1852 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Lot and his heirs, follow by Princess Victoria and her heirs, would succeed in the case their brother died without any legitimate heirs.[18] The change was made shortly before the death of Prince Albert Kamehameha, the only son of Kamehameha IV, on August 23, 1862.[19]

Victoria constitutionally assumed the power of state for a day when her brother Kamehameha IV died leaving no designated heirs in 1864. Section II Article 47 of the 1852 Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom provided that the Kuhina Nui (Premier), in absence of a monarch, would fill the vacant office.

Whenever the throne shall become vacant by reason of the King's death, or otherwise, and during the minority of any heir to the throne, the Kuhina Nui, for the time being, shall, during such vacancy or minority, perform all the duties incumbent on the King, and shall have and exercise all the powers, which by this Constitution are vested in the King.

After consulting with the Privy Councilors, she proclaimed in front the Legislature:

It having pleased Almighty God to close the earthly career of King Kamehameha IV, at a quarter past 9 o'clock this morning, I, as Kuhina Nui, by and with the advice of the Privy Council of State hereby proclaim Prince Lot Kamehameha, King of Hawaii, under the style and title of Kamehameha V. God preserve the King![20]

Betrothal

Victoria was betrothed to William Charles Lunalilo. Their parents had planned out their marriage from infancy and it was popular among the Hawaiians. The date was set, but they were forbidden to marry by her brothers Kamehameha IV and Kamehameha V, and the wedding was cancelled.[21][22] The reason was because the children of Victoria and Lunalilo would have a higher rank or mana than the brothers' own lines. In fact Kamehameha IV had tried to split them apart by engaging Victoria to David Kalākaua, and Lunalilo to Lydia Kamakaʻeha.[23][12]

Scandal

In 1857, a scandal involved Victoria and Marcus Cummins Monsarrat (1828–1871), a married English auctioneer. Monsarrat had been a friend to her two brothers and was a frequent dinner guest. One night, on January 15, 1857, Prince Lot was informed that Monsarrat was in the princess' bedroom. He immediately went to her room and caught Victoria in a compromising position and Monsarrat in the act of "arranging his pantaloons". The enraged Prince told him to leave or he would kill him. When Kamehameha IV found out about the incident, he blamed Lot for not "shooting Monsarrat down like a dog."[24]

Kamehameha IV subsequently banished Monsarrat from Hawaiʻi on May 20, 1857:

Whereas, Marcus C. Monsarrat, a naturalized subject of this Kingdom, is guilty of having perpetuated a grievous injury to Ourselves and to Our Royal family, And Whereas, such injury is of such a character as in Our judgement, to authorize and require the expulsion of the said M. C. Monsarrat from Our Dominions...Now, therefore, know that We, in the exercise of the Power vested in Us by virtue of Our office as Sovereign of this Kingdom...do hereby order that the said Marcus C. Monsarrat be forthwith expelled from this Kingdom; and he is hereby strictly prohibited forever, from returning to any part of Our Dominions, under penalty of Death.[25]

Monsarrat did, in fact, return and the King had him imprisoned and exiled again. Often accounted as Princess Victoria Kamāmalu's misbehavior and a love affair between the two, the contemporaneous Charles de Varigny defended the princess by saying Monsarrat's "insolence reached a point at which the princess was obliged to cry for help".[26]

Her brothers were in the process of marrying her to Kalākaua around 1857. The Monsarrat scandal either ended this arrangement[24][27] or was arranged to cover up the scandal.[22] In her memoir, Liliʻuokalani wrote, "I received a letter from my brother Kalākaua, telling me that he was engaged to the Princess Victoria, and asking me to come to Honolulu...[B]ut upon my arrival I found that the engagement was broken, for the Princess Victoria had gone to Wailua, and my brother had heard nothing from her for a fortnight."[28] Liliʻuokalani, remaining silent on the royal scandal, mentioned that the match was ultimately terminated when the princess decided to renew her on-and-off betrothal to Lunalilo.[29][30] Historian Kīhei de Silva noted that Kalākaua was willing in the union, but Kamāmalu refused the match.[22]

For the last few years of her life, she was rarely seen in public.[31] She remained a spinster for the remaining part of her life.[22]

Crown Princess

Victoria was an expected heir to the throne throughout her life because both her brothers were unable to leave surviving issue of their own. In fact, she was appointed as Heiress Apparent and crown princess by her brother King Kamehameha V in 1863. She would have become queen of Hawaii upon her brother's death, but she predeceased him.

Considered pro-American, the princess had a close friendship with the American missionaries. Musically gifted, she was an accomplished pianist and vocalist, and she sat at the melodeon and led the choir of Kawaiahao Church for many years. The Minister of Foreign Affairs, Robert Crichton Wyllie, considered it improper that a royal princess would sing in a choir and tried to convince her to stop, but she stayed loyal to the American missionaries at Kawaiahao. When the royal family switched from the Congregational Calvinist faith to the Anglican Church of Hawaii (originally known as the Hawaiian Reformed Catholic Church), Victoria refused to abandon her previous faith.[32][33] She was also a poet and chanter and composed chants and mele in the traditional Hawaiian style including many on her nephew Prince Albert Kamehameha.[34][35]

In 1863, Victoria founded the Kaʻahumanu Society, an organization concerned with the welfare of the ill and elderly Hawaiians, originally to nurse the victims of the smallpox epidemic.[36][37][38]

Death

Kamāmalu became ill during a party given at the Bishop's residence in Haleākala, Honolulu, in February 1866. The illness continued and resulted in paralysis in early May.[37] She became bedridden for the last three weeks of her life. The physicians Seth Porter Ford and Ferdinand William Hutchison were consulted although not much hope was given to her recovery. Her brother Lot wrote to Queen Emma who was abroad in Europe at the time, "But thanks to a vigorous constitution and still young, she has rallied", and he wished Emma would see Victoria alive when she returned. The princess was suffering from much pain, swelling in the body, and was unable to move without assistance. She was nursed by her ladies-in-waiting Nancy Sumner and Liliʻuokalani.[39] The Honolulu English language newspaper The Pacific Commercial Advertiser reported, "On Sunday she was better, but her disease took an unfavorable turn soon after".[31] Kamāmalu did not recover and died at 10 a.m. on May 29, 1866, at Papakanene house at Mokuʻaikaua, at the age of 27.[22][31]

The exact illness that caused her death has never been discussed in detail. The official statement was that she died "imprudently bathing while heated".[40][41] Mark Twain was in Honolulu at the time and wrote favorably of her in his public correspondence to the Sacramento Daily Union. However, privately in his notebook, he wrote, "Pr. V. died in forcing abortion — kept half a dozen bucks to do her washing, & has suffered 7 abortions" and later described how she kept a harem of "thirty-six splendidly built young native men" who were present at her funeral.[40][42]

Victoria's childless death left her brother the king without obvious heirs.[43] Her brother, a bachelor throughout his life, had intended that she should be his heir. Her death left her brother without an obvious successor. After his brother's death in 1872 an election was held between Kalākaua and Lunalilo, both former suitors of the princess. Lunalilo easily won the election, yet his reign lasted less than a year.

Victoria died without a written will, so her vast landholdings, including much of the original private lands of her mother and Queen Kaʻahumanu, were inherited by her father and eventually passed to her half-sister Keʻelikōlani who willed them to Bernice Pauahi Bishop and from whence they became part of the Kamehameha Schools. The Kaʻahumanu Society went to the wayside after her death, but Lucy Kaopaulu Peabody reorganized the club in 1905, and it continues to this day.

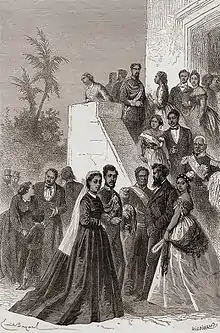

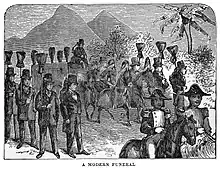

Funeral

The Legislature had to raise $6,000 for her funeral expenses including a coffin made from fine kou and koa wood.[44] Her funeral ceremony also revived many funeral rites of the Native Hawaiians including the kanikau (grief wailing) and public hula performances.[45] The wailing lasted for weeks. Many loyal Hawaiians walked as far as 50 miles to pay their last respects to their princess. Writing in high revolutionary fervor of the days immediately following the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, Professor William DeWitt Alexander remarked:

It is true that the germs of many evils of Kalakaua's reign may be traced to the reign of Kamehameha V. The reactionary policy of that monarch is well known. Under him the "recrudescence" of heathenism commenced, as evidenced by the Pagan orgies at the funeral of his sister Victoria Kamāmalu, in June, 1866, and his encouragement of lascivious hula hula dancers and the pernicious class of Kahunas or sorcerers. Closely connected with this reaction was a growing jealousy and hatred of foreigners.[46]

Mark Twain, a spectator to the events, also labeled the acts of the grieving Hawaiians as "pagan orgies." Twain had his letters sent to his newspaper in Sacramento and he later published his observations in the book Roughing It. He didn't understand that for the last years of the Princess' life, she had become disillusioned with Western modernization and retreated to the ancient Hawaiian traditions, and the funeral ceremonies were her brother's way of honoring her dying wishes.[46]

Honours

Dame Grand Cross of the Most Noble Order of Kamehameha I.

Dame Grand Cross of the Most Noble Order of Kamehameha I.

References

- Rose, Conant & Kjellgren 1993, pp. 278–279.

- Forbes 2001, p. 426.

- Kam 2017, pp. 80–82.

- "United States: Hawaii: Heads of State: 1810–1898 – Archontology.org". Archontology.org. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- Ii, Pukui & Barrère 1983, p. 161.

- "Royal Family of Hawaii". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu. April 1, 1874. p. 3. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- Katharine Luomala, University of Hawaii (1987). "Reality and Fantasy: The Foster Child in Hawaiian Myths and Customs". Pacific Studies. Brigham Young University Hawaii Campus. pp. 28–29. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- Pratt 1920, p. 53.

- Cooke & Cooke 1937, p. vi.

- "Princes and Chiefs eligible to be Rulers". The Polynesian. 1 (9). Honolulu. July 20, 1844. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- Van Dyke 2008, p. 364.

- Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 10–15.

- Kanahele 2002, p. 55–78.

- Kuykendall 1965, pp. 166, 267.

- Kuykendall 1953, p. 36.

- "Victoria Kamāmalu". Hawaii State government archives web site. Archived from the original on June 27, 2009. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- Taylor 1929, pp. 24, 29.

- "Articles of Amendment of the Constitution, proposed and passed pursuant to the 105th Article of the Constitution". The Polynesian. Honolulu. August 16, 1862. p. 3.

- Kanahele 1999, p. 139.

- Comeau 1996, p. 27.

- "Alekoki". Huapala.org. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- Silva

- Allen 1982, pp. 81–90.

- Kanahele 1999, p. 79.

- Forbes 2001, pp. 198–199.

- Varigny 1874, p. 86; Varigny 1981, p. 64

- Haley 2014, p. 197.

- Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 13–14.

- Allen 1995, pp. 33–34.

- Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 12–15.

- The Pacific Commercial Advertiser 1866.

- Twain 1938, pp. 96–97.

- Tranquada & King 2012, p. 30.

- Peterson 1984, p. 193.

- Cracroft, Franklin & Queen Emma 1958, pp. 302–303.

- Kanahele 1999, p. 188.

- Peterson 1984, p. 194.

- Allen 1982, pp. 98–99.

- Topolinski 1975, pp. 51-52.

- Scharnhorst 2018, pp. 341–342.

- The New York Herald 1866.

- Twain 1975, p. 129.

- Kuykendall 1953, pp. 239–242.

- Twain 1938, pp. 100–101.

- Silva 2000, pp. 43–44.

- "HAWAII : Monarchy In Hawaii – Part 2". Janesoceania.com. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

Bibliography

- Books and journals

- Allen, Helena G. (1982). The Betrayal of Liliuokalani: Last Queen of Hawaii, 1838–1917. Glendale, CA: A. H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0-87062-144-4. OCLC 9576325.

- Comeau, Rosalin Uphus (1996). Kamehameha V: Lot Kapuāiwa. Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools Press. ISBN 978-0-87336-039-5. OCLC 34752213.

- Cooke, Amos Starr; Cooke, Juliette Montague (1937). Richards, Mary Atherton (ed.). The Chiefs' Children School: A Record Compiled from the Diary and Letters of Amos Starr Cooke and Juliette Montague Cooke, by Their Granddaughter Mary Atherton Richards. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin. OCLC 1972890.

- Cracroft, Sophia; Franklin, Jane; Queen Emma (1958). Korn, Alfons L. (ed.). The Victorian Visitors: An Account of the Hawaiian Kingdom, 1861–1866, Including the Journal Letters of Sophia Cracroft: Extracts from the Journals of Lady Franklin, and Diaries and Letters of Queen Emma of Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. hdl:10125/39981. ISBN 978-0-87022-421-8. OCLC 8989368.

- Forbes, David W., ed. (2001). Hawaiian National Bibliography, 1780–1900, Volume 3: 1851–1880. 3. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2503-4. OCLC 123279964.

- Gregg, David L. (1982). King, Pauline (ed.). The Diaries of David Lawrence Gregg: An American Diplomat in Hawaii, 1853–1858. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society. OCLC 8773139.

- Haley, James L. (2014). Captive Paradise: A History of Hawaii. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-60065-5. OCLC 865158092.

- Ii, John Papa; Pukui, Mary Kawena; Barrère, Dorothy B. (1983). Fragments of Hawaiian History (2 ed.). Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-910240-31-4. OCLC 251324264.

- Kaeo, Peter; Queen Emma (1976). Korn, Alfons L. (ed.). News from Molokai, Letters Between Peter Kaeo & Queen Emma, 1873–1876. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii. hdl:10125/39980. ISBN 978-0-8248-0399-5. OCLC 2225064.

- Kam, Ralph Thomas (2017). Death Rites and Hawaiian Royalty: Funerary Practices in the Kamehameha and Kalakaua Dynasties, 1819–1953. S. I.: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4766-6846-8. OCLC 966566652.

- Kameʻeleihiwa, Lilikalā (1992). Native Land and Foreign Desires. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press. pp. 107, 124–27, 146, 207, 213, 218, 228, 229, 254, 303, 307, 310, death of, 290, 309, genealogy of, 101, 119, 123, 231. ISBN 0-930897-59-5. OCLC 154146650.

- Kanahele, George S. (1999). Emma: Hawaii's Remarkable Queen. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2240-8. OCLC 40890919.

- Kanahele, George S. (2002) [1986]. Pauahi: The Kamehameha Legacy. Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools Press. ISBN 978-0-87336-005-0. OCLC 173653971.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1965) [1938]. The Hawaiian Kingdom 1778–1854, Foundation and Transformation. 1. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-87022-431-X. OCLC 47008868.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1953). The Hawaiian Kingdom 1854–1874, Twenty Critical Years. 2. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-432-4. OCLC 47010821.

- Liliuokalani (1898). Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen, Liliuokalani. Boston: Lee and Shepard. ISBN 978-0-548-22265-2. OCLC 2387226.

- Peterson, Barbara Bennett, ed. (1984). Notable Women of Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0820-4. OCLC 11030010.

- Osorio, Jon Kamakawiwoʻole (2002). Dismembering Lāhui: A History of the Hawaiian Nation to 1887. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2549-7. OCLC 48579247.

- Parker, David "Kawika" (2008). "Crypts of the Ali`i The Last Refuge of the Hawaiian Royalty". Tales of Our Hawaiʻi (PDF). Honolulu: Alu Like, Inc. OCLC 309392477. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 11, 2013.

- Pratt, Elizabeth Kekaaniauokalani Kalaninuiohilaukapu (1920). History of Keoua Kalanikupuapa-i-nui: Father of Hawaii Kings, and His Descendants, with Notes on Kamehameha I, First King of All Hawaii. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin. OCLC 154181545.

- Rose, Roger G.; Conant, Sheila; Kjellgren, Eric P. (September 1993). "Hawaiian Standing Kāhili in the Bishop Museum: An Ethnological and Biological Analysis". Journal of the Polynesian Society. Wellington, NZ: Polynesian Society. 102 (3): 273–304. JSTOR 20706518.

- Scharnhorst, Gary (2018). The Life of Mark Twain: The Early Years, 1835-1871. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-7400-7. OCLC 1007505891.

- Silva, Noenoe K. (2000). "Kanawai E Ho'opau I Na Hula Kuolo Hawai'i: the Political Economy of Banning the Hula". The Hawaiian Journal of History. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society. 34: 29–48. hdl:10524/347. OCLC 60626541.

- Taylor, Albert Pierce (October 15, 1929). "Intrigues, conspiracies and accomplishments in the era of Kamehameha IV and V and Robert Crichton Wyllie". Papers of the Hawaiian Historical Society. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society. 16: 16–32. hdl:10524/978. OCLC 528831753.

- Topolinski, John Renken Kahaʻi (1975). Nancy Sumner: A Part-Hawaiian High Chiefess, 1839–1895. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. OCLC 16326376.

- Tranquada, Jim; King, John (2012). The ʻUkulele: A History. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3544-6. OCLC 767806914 – via Project MUSE.

- Twain, Mark (1938). Letters from the Sandwich Islands: Written for the Sacramento Union. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. pp. 16–137. OCLC 187974.

- Twain, Mark (1975). Anderson, Frederick; Frank, Michael B.; Sanderson, Kenneth M. (eds.). Mark Twain's Notebooks & Journals, Volume I: (1855–1873). Oakland, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-90538-2. OCLC 2015814.

- Twain, Mark (1872). Roughing it. New York: Hippocrene Books. pp. 490–497. ISBN 978-0-87052-707-4. OCLC 19256406.

- Van Dyke, Jon M. (2008). Who Owns the Crown Lands of Hawaiʻi?. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3211-7. OCLC 163812857.

- Varigny, Charles Victor Crosnier de (1874). Quatorze ans aux îles Sandwich. Paris: Hachette et cie. OCLC 191324680.

- Varigny, Charles Victor Crosnier de (1981). Fourteen Years in the Sandwich Islands, 1855–1868. Translated by Alfons L. Korn. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0709-2. OCLC 456816908.

- Newspapers and online sources

- "La Hanai O Ke Kama Alii Wahine". Ka Nupepa Kuokoa. 3 (45). Honolulu. November 5, 1864. p. 2. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Ka Make ana o Ka Mea Kiekie Ke Kama Aliiwahine Victoria Kamamalu Kaahumanu". Ka Nupepa Kuokoa. 5 (22). Honolulu. June 2, 1866. p. 2. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Death of the Heir Apparent". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. June 2, 1866. p. 2. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Hawaiian Legislature". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. June 2, 1866. p. 1. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Hawaiian Legislature". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. June 9, 1866. p. 1. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Programme Of The Funeral Of Her Later Royal Highness the Princess Victoria Kamamalu Kaahumanu". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. June 30, 1866. p. 2. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "A Novel Recreation". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. June 30, 1866. p. 3. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Miscellaneous". The New York Herald. Honolulu. July 30, 1866. p. 4. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- Silva, Kīhei de. "ʻAlekoki Revisited". Kaleinamanu Library Archives, Kamehameha Schools. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Victoria Kamāmalu. |

- March 27, 1855. New York Times article on her

- Mark Twain in Sacramento Union – #14

- Victoria Kamamalu on a Stamp

- Hawai'i's Lost Princess: Princess Victoria Kamāmalu Ka'ahumanu IV

- Victoria Kamamalu "A Worthy Successor" by Julie Stewart Williams

| Preceded by Keoni Ana |

Kuhina Nui of the Hawaiian Islands January 16, 1855 – December 21, 1863 |

Succeeded by Kekūanāoʻa |