Kamehameha IV

Kamehameha IV (Alekanetero ʻIolani Kalanikualiholiho Maka o ʻIouli Kūnuiākea o Kūkāʻilimoku; anglicized as Alexander Lihoiho[2]) February 9, 1834 – November 30, 1863), reigned as the fourth monarch of Hawaii under the title Ke Aliʻi o ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻAina of the Kingdom of Hawaii from January 11, 1855 to November 30, 1863.

| Kamehameha IV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |||||

| King of the Hawaiian Islands (more...) | |||||

| Reign | January 11, 1855 – November 30, 1863 | ||||

| Investiture | January 11, 1855 Kawaiahaʻo Church | ||||

| Predecessor | Kamehameha III | ||||

| Successor | Kamehameha V | ||||

| Kuhina Nui | Keoni Ana Kaʻahumanu IV | ||||

| Born | February 9, 1834 Honolulu, Oʻahu | ||||

| Died | November 30, 1863 (aged 29) Honolulu, Oʻahu | ||||

| Burial | February 3, 1864[1] Mauna ʻAla Royal Mausoleum | ||||

| Spouse | Emma | ||||

| Issue | Albert Edward Kauikeaouli | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Kamehameha | ||||

| Father | Kekūanāoʻa Kamehameha III (hānai) | ||||

| Mother | Kīnaʻu Kalama (hānai) | ||||

| Religion | Church of Hawaii | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Early life

Alexander was born on February 9, 1834 in Honolulu on the island of Oʻahu. His father was High Chief Mataio Kekūanāoʻa, Royal Governor of Oʻahu. His mother was Princess Elizabeth Kīnaʻu the Kuhina Nui or Prime Minister of the Kingdom. He was the grandson of Kamehameha I, first monarch of all the islands. Alexander had three older brothers, David Kamehameha, Moses Kekūāiwa and Lot Kapuāiwa, and a younger sister, Victoria Kamāmalu.[3]

As a toddler, Alexander was adopted by his uncle, King Kamehameha III who decreed Alexander heir to the throne and raised him as the crown prince.[4]

His name 'Iolani means "hawk of heaven", or "royal hawk".[5]

Education and travel

Alexander Liholiho was educated by Congregationalist missionaries Amos and Juliette Cooke at the Chiefs' Children's School (later known as Royal School) in Honolulu. He was accompanied by 30 attendants (kahu) when he arrived, but they were sent home and for the first time Liholiho was on his own.[3] Alexander Liholiho played the flute and the piano, and enjoyed singing, acting, and cricket.[6]

When he was 14 he left the Royal School and went to study law.[3]

At the age of 15, he went on a government trip to England, the United States, and Panama. Liholiho recorded the events of his trip in a journal.[3]

A diplomatic mission was planned following Admiral de Tromelin's 1849 attack on the fort of Honolulu, the result of French claims stemming back twenty years to the expulsion of Catholic missionaries. Contention surrounded three issues: regulations of Catholic schools, high taxes on French brandy, and the use of French language in transactions with the consul and citizens of France. Although this struggle had gone on for many years, the Hawaiian king finally sent Gerrit P. Judd to try for the second time to negotiate a treaty with France. Envoys Haʻalilio and William Richards had gone on the same mission in 1842 and returned with only a weak joint declaration. It was hoped the treaty would secure the islands against future attacks such as the one it had just suffered at the hands of Admiral de Tromelin. Advisors to Kamehameha III thought it best that the heir apparent, Alexander, and his brother, Lot Kapuāiwa, would benefit from the mission and experience.

With the supervision of their guardian Dr. Judd, Alexander and his brother sailed to San Francisco in September 1849.[7][8] After their tour of California, they continued on to Panama, Jamaica, New York City, and Washington, D.C. They toured Europe and met with various heads of state, aiming to secure recognition of Hawaii as an independent country.[3] Speaking both French and English, Alexander was well received in European society. He met president of France Louis Napoleon. Sixteen-year-old Alexander Liholiho described a reception given at the Tuileries by:

General La Hitte piloted us through the immense crowd that was pressing on from all sides, and finally we made our way to the president...Mr. Judd was the first one taken notice of, and both of them made slight bows to each other. Lot and myself then bowed, to which the (Louis Napoleon) returned with a slight bend of the vertebras. he then advanced and said, "This is your first visit to Paris", to which we replied in the affirmative. He asked us if we liked Paris to which we replied, very much, indeed. He then said, I am very gratified to see you, you having come from so far a country, he then turned towards the doctor and said, I hope our little quarrel will be settled. to which the Doctor replied. "We put much confidence in the magnanimity and Justice of France."

Failing to negotiate a treaty with France during three months in Paris, the princes and Judd returned to England. They met Prince Albert, Lord Palmerston, and numerous other members of British aristocracy. They had an audience with Prince Albert since Queen Victoria was retired from public view, awaiting the birth of her seventh child, Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught.[3]

Prince Alexander accounted:

When we entered, the prince was standing a little aside of the door, and bowed to each of us as we came in. He was a fine man, about as tall as I am, and had a very fine bust, and straight legs. We kept standing, Palmerston on my right, and the doctor on my left, and then Lot. the prince began the conversation by asking if we intended to make a long stay (in London) to which I answered by saying that we expected to leave in about a week and then Mr. Judd made a few remarks on his business.

In May 1850, the royal brothers, boarded a ship in England and sailed to the United States for a more extensive stay before returning. At Washington D.C., they met with President Zachary Taylor and Vice President Millard Fillmore. He experienced American racism first hand when he was almost removed from his train car after being mistaken for a slave. The prince had preceded Dr. Judd and Prince Lot in occupying the compartment reserved for them for a return trip to New York and someone had arrived at the door of the compartment and questioned Alexander's right to be there.[9][3] The prince wrote in his journal:

I found he was the conductor, and took me for somebody's servant just because I had a darker skin than he had. Confounded fool;. the first time that I have ever received such treatment, not in England or France or anywhere else........In England an African can pay his fare and sit alongside Queen Victoria. The Americans talk and think a great deal about their liberty, and strangers often find that too many liberties are taken of their comfort just because his hosts are a free people.

At a dinner party in New York with friends of Judd, the princes were again exposed to a racist incident. Helen Kinau Wilder recalled in her memoirs:[9]

In Geneva (New York), visiting friends, the butler was very averse to serving "blacks" as he called them, and revenged himself by putting bibs at their places. Alexander unfolded his, saw the unusual shape, but as he had seen many strange things on his travels concluded that must be something new, so quietly fitted the place cut out for the neck to his waist. their hostess was very angry when she found what a mean trick her servant had played on them.[9]

These displays of prejudice in the United States and the puritanical views of American missionaries probably influenced his slightly anti-American point of view,[10] along with that of the rest of the royal family. Judd later wrote about him: "educated by the Mission, most of all things dislikes the Mission. Having been compelled to be good when a boy, he is determined not to be good as a man."[11]

Succession

Upon his return Alexander was appointed to the Privy Council and House of Nobles of Kamehameha III in 1852.[12] He had the opportunity to gain administrative experience that he would one day employ as King. During his term he also studied foreign languages and became accustomed to traditional European social norms.

He assumed the duties of Lieutenant General and Commander in Chief of the Forces of the Hawaiian Islands and began working to reorganize the Hawaiian military and to maintain the dilapidated forts and cannons from the days of Kamehameha I. During this period, he appointed many officers to assist him including his brother Lot Kapuāiwa, Francis Funk, John William Elliott Maikai, David Kalākaua, John Owen Dominis and others to assist him.[13][14][15] He also worked with Robert Crichton Wyllie, the secretary of war and navy and the minister of foreign affairs, who supported creating a Hawaiian army to protect the islands from California adventurers and filibusters who were rumor to be planning to invade the islands.[16]

Reign

Kamehameha III died on March 18, 1854. On January 11, 1855 Alexander took the oath as King Kamehameha IV, succeeding his uncle when he was only 20 years old. His first act as king was to halt the negotiations his father had begun regarding Hawaii's annexation by the United States.[3]

His cabinet ministers were: Wyllie, as minister of foreign affairs, Keoni Ana (John Young II) served as minister of the interior, Elisha Hunt Allen as minister of finance, and Richard Armstrong as minister of education. William Little Lee served as chief justice, until he was sent on a diplomatic mission and then died in 1857. Allen became chief justice, and David L. Gregg became minister of finance. After Keoni Ana died, his brother Prince Lot Kapuāiwa was minister of the interior.[17]:36

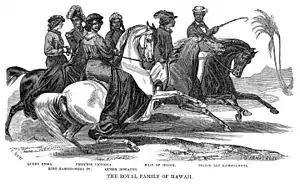

Only a year after assuming the throne, Alexander took the hand of Emma Rooke, whom he had met in childhood at the Chiefs' Children's School, as his queen.[3] Queen Emma was the granddaughter of John Young, Kamehameha the Great's British royal advisor and companion. She also was Kamehameha's great-grandniece.[3] On the day of their wedding, he forgot their wedding ring. Chief Justice Elisha Hunt Allen quickly slipped his own gold ring to the king and the ceremony continued.[18] The marriage was apparently a happy one, as the king and queen shared interests including opera, literature and theatre.[3]

After marrying in 1856, the royal couple had their only child on May 20, 1858, named Prince Albert Edward Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa a Kamehameha.[3] Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was Prince Albert's godmother (by proxy) at his christening in Honolulu. Alexander Liholiho thought he was responsible for the death of Prince Albert because he gave him a cold shower to "cool him off" when Albert wanted something he could not have.[19] His ailing health worsened. At the age of four, the young prince died on August 27, 1862. The cause of the prince's death is unknown: at the time, it was believed to be "brain fever" or meningitis. Later speculation has included appendicitis.[3]

On September 11, 1859 the king shot Henry A. Neilson, his secretary and one of his closest friends, who died two years later.[20] Alexander had heard a rumour that Neilson was having an affair with Queen Emma, and after drinking heavily shot his friend in the chest.[3][19] Following the shooting, the king apologised to Neilson and provided him with the use of his Waikiki home for the rest of his life.[3] He also considered abdicating his throne, before being convinced not to by Wyllie, his minister of foreign affairs.[19]

Wyllie sponsored a fancy dress ball in 1860. Even the Catholic bishop came, dressed as a bishop. Kamehameha IV's father Kekūanāoʻa came in Scottish highland dress, music was provided by German musicians, and the food by a French chef. Emma came as the earth goddess Cybele. The conservative American missionaries did not approve, especially of the dancing.[11]

In August 1861 he issued a declaration of neutrality in the American Civil War.[21]

Resisting American influence

At the time of Alexander's assumption to the throne, the American population in the Hawaiian islands continued to grow and exert economic and political pressure in the Kingdom. Sugar producers, in particular, pushed for annexation by the United States in order to have free trade with the United States.[3] Alexander worried that the United States of America would make a move to conquer his nation; an annexation treaty was proposed in Kamehameha III's reign. He strongly felt that annexation would mean the end of the monarchy and the Hawaiian people.

Liholiho instead wanted a reciprocity treaty, involving trade and taxes, between the United States and Hawaii. He was not successful, as sugar plantation owners in the southern United States lobbied heavily against the treaty, worried that competition from Hawaii would harm their industries.[3] In an effort to balance the amount of influence exerted by American interests, Alexander began a campaign to limit Hawaii's dependence on American trade and commerce. He sought deals with the British and other European governments, but his reign did not survive long enough to make them.

In 1862, as part of his atonement for shooting his secretary and friend Neilson, he translated the Book of Common Prayer into the Hawaiian language.[22][19]

Legacy

Alexander and Queen Emma devoted much of their reign to providing quality healthcare and education for their subjects. They were concerned that foreign ailments and diseases like leprosy and influenza were decimating the native Hawaiian population.[3] In 1855, Alexander addressed his legislature to promote an ambitious public healthcare agenda that included the building of public hospitals and homes for the elderly. The legislature, empowered by the Constitution of 1852 which limited the King's authority, struck down the healthcare plan. Alexander and Queen Emma responded to the legislature's refusal by lobbying local businessmen, merchants and wealthy residents to fund their healthcare agenda. The fundraising was an overwhelming success and the royal couple built The Queen's Medical Center. The fundraising efforts also yielded separate funds for the development of a leprosy treatment facility built on the island of Maui.[23]

In 1856, Kamehameha IV decreed that December 25 would be celebrated as the kingdom's national day of Thanksgiving, accepting the persuasions of the conservative American missionaries who objected to Christmas on the grounds that it was a pagan celebration. Six years later, he would rescind his decree and formally proclaim Christmas as a national holiday of the Kingdom of Hawaii. The first Christmas tree would come into the islands during his brother's reign.[18]

Under his eight-year reign the Kingdom saw the many territory additions. Laysan Island was annexed on May 1, 1857, Lisianski Island was annexed on May 10, 1857, and Palmyra Atoll was annexed on April 15, 1862. Some residents of Sikaiana near the Solomon Islands believe their island was annexed by Kamehameha IV to Hawaii in 1856 (or 1855). Some maintain that through this annexation, Sikaiana has subsequently become part of the United States of America through the 1898 annexation of "Hawaii and its dependencies". The U.S. disagrees.[24]

End of reign

Alexander died of chronic asthma on November 30, 1863, and was succeeded by his brother, who took the name Kamehameha V.[25] At his funeral, eight hundred children and teachers walked to say goodbye. He was buried with his son at the Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii on February 3, 1864.[26]

Queen Emma remained active in politics. With the end of the Kamehameha dynasty and King William C. Lunalilo dying without an heir of his own, Queen Emma ran unsuccessfully to become the Kingdom's ruling monarch. She lost to David Kalākaua who would establish a dynasty of his own — the last to rule Hawaii.[27]

Alexander (as Kamehameha IV) and Emma are honored with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America on November 28 called the Feast of the Holy Sovereigns.[28]

References

- David W. Forbes, ed. (2001). Hawaiian national bibliography, 1780–1900. 3. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 373–374. ISBN 0-8248-2503-9.

- "Kamehameha IV | king of Hawaii". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- Lowe, Ruby Hasegawa.; Racoma, Robin Yoko (1997). Kamehameha IV, Alexander Liholiho. Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools Press. ISBN 0-87336-045-1. OCLC 35977915.

- Cooke, Richards & Cooke 1937, p. 357.

- Hawaiianencyclopedia

- Cooke, Richards & Cooke 1937, pp. vi, xvi, 46, 54, 105, 224, 263–264, 298, 328.

- Kuykendall 1965, pp. 395–398.

- Baur 1922, pp. 246–248.

- Jane Resture. "Monarchy In Hawaii". Jane's Oceania web site. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- "Kamehameha IV - Hawaii History - Monarchs". www.hawaiihistory.org. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- Gavan Daws (1967). "Decline of Puritanism at Honolulu in the Nineteenth Century". Hawaiian Journal of History. 1. Hawaii Historical Society. pp. 31–42. hdl:10524/400.

- "Alexander Liholiho office record". state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Archived from the original on October 7, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- "Death of Hon. J. W. E. Maikai". The Polynesian. Honolulu. June 2, 1860. p. 2.

- "By Authority". The Polynesian. Honolulu. November 5, 1853. p. 2.

- MacKaye, D. L. (May 8, 1910). "Tales From The Archives – Defending Honolulu". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. p. 4.

- Judd, Laura Fish (1880). Honolulu: Sketches of Life: Social, Political, and Religious, in the Hawaiian Islands from 1828–1861. With a Supplementary Sketch of Events to the Present Time. New York: Anson D. F. Randolph & Company. pp. 219–221. OCLC 300479.

- Ralph Simpson Kuykendall (1953). Hawaiian Kingdom 1854–1874, twenty critical years. 2. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-432-4.

- George S. Kanahele (1999). Emma: Hawai'i's Remarkable Queen: a Biography. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2240-8.

- "| Kamehameha IV and the Shooting of Henry Neilson". www.honolulumagazine.com. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Thomas George Thrum, ed. (1904). "The Kamehameha IV – Neilson tragedy". Thrum's Hawaiian annual and standard guide. Honolulu Star-Bulletin. pp. 86–91.

- "Proclamation: Kamehameha IV King of the Hawaiian Islands (Printed Proclamation of Neutrality)". Abraham Lincoln papers. U.S. Library of Congress. August 26, 1861. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- Kamehameha IV (June 1863). "Preface to the Book of Common Prayer". booklet presented to the 58th General Convention of the Episcopal Church in 1955 by Meiric K. Dutton. Retrieved January 29, 2010.

- Greer, Richard A. (1969). "Founding of the Queen's Hospital". Hawaiian Journal of History. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society. 3: 110–145. hdl:10524/288. PMID 11632066.

- "U.S. Insular Areas: Application of the U.S. Constitution" (PDF). United States Government Accounting Office. November 1997. Retrieved November 27, 2009. page 39, footnote 2

- "Death of His Majesty Kamehameha IV". December 3, 1863. p. Image 2. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

- Kam 2017, pp. 74-75.

- Kuykendall 1967, pp. 3–16.

- The Book of common prayer and administration of the sacraments and other rites and ceremonies of the church. Church Publishing, Incorporated, New York. 1979. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-89869-060-6.

Bibliography

- Baur, John E. (1922). "When Royalty Came To California". California Historical Society Quarterly. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society. 67: 244–264.

- Cooke, Amos Starr; Richards, Mary (Atherton) Mrs.; Cooke, Juliette (Montague) Mrs. (1937). The Chiefs' children's school a record compiled from the diary and letters of Amos Starr Cooke and Juliette Montague Cooke, by their granddaughter. Mary Atherton Richards. Honolulu, HI: Honolulu Star-Bulletin – via HathiTrust.

- Kam, Ralph Thomas (2017). Death rites and Hawaiian royalty : funerary practices in the Kamehameha and Kalākaua dynasties, 1819/1953. ISBN 978-1-4766-6846-8.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1965) [1938]. The Hawaiian Kingdom 1778–1854, Foundation and Transformation. 1. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-87022-431-X. OCLC 47008868.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1953). The Hawaiian Kingdom 1854–1874, Twenty Critical Years. 2. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-432-4. OCLC 47010821.

- Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1967). The Hawaiian Kingdom 1874–1893, The Kalakaua Dynasty. 3. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-433-1. OCLC 500374815.

- Lowe, Ruby Hasegawa; Racoma, Robin Yoko (1996). Kamehameha IV, Alexander Liholiho. Kamehameha Schools Press. ISBN 0-87336-045-1.

Further reading

- Jacob Adler, ed. (1967). The Journal of Prince Alexander Liholiho, The Voyages Made to the United States, England and France in 1849–1850. The University of Hawaii Press for The Hawaiian Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-608-00534-8.

- Ruby Hasegawa Lowe, Robin Yoko Racoma (1996). Kamehameha IV, Alexander Liholiho. Kamehameha Schools Press. ISBN 0-87336-045-1.

- Elizabeth Waldron (1986). Liholiho and Emma: King Kamehameha IV and His Queen. Daughters of Hawaii. ISBN 0-938851-00-4.

- Laws of His Majesty Kamehameha IV., king of the Hawaiian Islands, passed by the nobles and representatives, at their session, 1855. Printed by order of the Government. 1855 – via HathiTrust.

- Kamehameha IV (1861). Speeches of His Majesty Kamehameha IV: to the Hawaiian Legislature ... Printed at the Government Press – via HathiTrust.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kamehameha IV. |

- "Biography of Founder King Kamehameha IV". The Queen's Hospital web site. Retrieved January 29, 2010.

- "Alexander Liholiho: Kamehameha IV". Aloha-Hawaii.com web site. Archived from the original on October 13, 2004. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- "Kamehameha IV (Alexander Liholiho) 1834–1863". hawaiihistory.org web site. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- Will Hoover (July 2, 2006). "King Kamehameha IV". Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- "Kamehameha IV". Biography from Hawaiʻi Royal Family web site. Kealii Pubs. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- Ua Nani `O Nu'uanu – Mele Inoa for Alexander Liholiho

- Works by Kamehameha IV at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Kamehameha IV at Internet Archive

| Royal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Kamehameha III |

King of Hawaiʻi 1855–1863 |

Succeeded by Kamehameha V |