Viral shedding

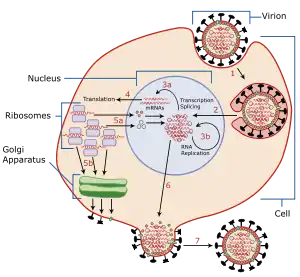

Viral shedding refers to the expulsion and release of virus progeny following successful reproduction during a host-cell infection. Once replication has been completed and the host cell is exhausted of all resources in making viral progeny, the viruses may begin to leave the cell by several methods.[1]

|

The term is used to refer to shedding from a single cell, shedding from one part of the body into another part of the body,[2] and shedding from bodies into the environment where the viruses may infect other bodies.[3]

Vaccine shedding refers to rare instances where potentially infective virions have been shed post vaccination.

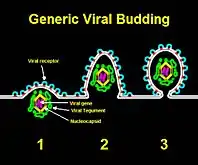

Via budding

"Budding" through the cell envelope—in effect, borrowing from the cell membrane to create the virus's own viral envelope—is most effective for viruses that need an envelope in the first place. These include enveloped viruses such as HIV, HSV, SARS or smallpox. When beginning the budding process, the viral nucleocapsid cooperates with a certain region of the host cell membrane. During this interaction, the glycosylated viral envelope protein inserts itself into the cell membrane. In order to successfully bud from the host cell, the nucleocapsid of the virus must form a connection with the cytoplasmic tails of envelope proteins.[4] Though budding does not immediately destroy the host cell, this process will slowly use up the cell membrane and eventually lead to the cell's demise. This is also how antiviral responses are able to detect virus-infected cells.[5] Budding has been most extensively studied for viruses of eukaryotes. However, it has been demonstrated that viruses infecting prokaryotes of the domain Archaea also employ this mechanism of virion release.[6]

Via apoptosis

Animal cells are programmed to self-destruct when they are under viral attack or damaged in some other way. By forcing the cell to undergo apoptosis or cell suicide, release of progeny into the extracellular space is possible. However, apoptosis does not necessarily result in the cell simply popping open and spilling its contents into the extracellular space. Rather, apoptosis is usually controlled and results in the cell's genome being chopped up, before apoptotic bodies of dead cell material clump off the cell to be absorbed by macrophages. This is a good way for a virus to get into macrophages either to infect them or simply travel to other tissues in the body.

Although this process is primarily used by non-enveloped viruses, enveloped viruses may also use this. HIV is an example of an enveloped virus that exploits this process for the infection of macrophages.[7]

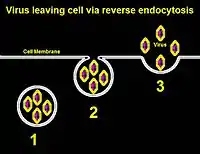

Via exocytosis

Viruses that have envelopes that come from nuclear or endosomal membranes can leave the cell via exocytosis, in which the host cell is not destroyed.[8] Viral progeny are synthesized within the cell, and the host cell's transport system is used to enclose them in vesicles; the vesicles of virus progeny are carried to the cell membrane and then released into the extracellular space. This is used primarily by non-enveloped viruses, although enveloped viruses display this too. An example is the use of recycling viral particle receptors in the enveloped varicella-zoster virus.[9]

Contagiousness

A person with a viral disease is contagious if they are shedding viruses. The rate at which an infected person sheds viruses over time is therefore of considerable interest. Some viruses such as HSV-2 (which produces genital herpes) can cause asymptomatic shedding and therefore spread undetected from person to person, as no fever or other hints reveal the contagious nature of the host during this kind of shedding.[10] Another crucial component to viral shedding is whether or not the age of the individual infected plays a role in how long the individual will shed the virus. The University of Milan conducted a study on the A/H1N1/2009 influenza virus to determine if the shedding of the novel pandemic occurs for a longer time in youth than in adults. Only children who had symptoms that appeared two days before hospital attendance, were under 15 years of age, and did not face any serious complications were included in the study. After physical exams and nasopharyngeal samples from all of the positive cases, the results determined that the length of viral shedding (in days) does not correspond to age. The virus shedding was not related to age because there was no difference between the children in the different age groups. Contagiousness in this situation could last up to 15 days, which means that when viral diseases infect much of a localized population, the proper quarantine precautions need to take place to prevent further spread of the virus through viral shedding.[11]

References

- N.J. Dimmock et al. "Introduction to Modern Virology, 6th edition." Blackwell Publishing, 20hif ilikr 07.

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health – Rabies Control Plan – Chapter 1: General Information – "Definitions as Used in this Document [...] Shedding – The release of rabies virus from the salivary glands into the saliva."

- Hall CB, Douglas RG, Geiman JM, Meagher MP (October 1979). "Viral shedding patterns of children with influenza B infection". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 140 (4): 610–3. doi:10.1093/infdis/140.4.610. PMID 512419.

- Payne, Susan (2017). "Virus Interactions With the Cell". Viruses: 23-25. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-803109-4.00003-9. ISBN 9780128031094. S2CID 90650541. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Pornillos O, Garrus JE, Sundquist WI (December 2002). "Mechanisms of enveloped RNA virus budding". Trends in Cell Biology. 12 (12): 569–79. doi:10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02402-9. PMID 12495845.

- Quemin ER, Chlanda P, Sachse M, Forterre P, Prangishvili D, Krupovic M (September 2016). "Eukaryotic-Like Virus Budding in Archaea". mBio. 7 (5). doi:10.1128/mBio.01439-16. PMC 5021807. PMID 27624130.

- Stewart SA, Poon B, Song JY, Chen IS (April 2000). "Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpr induces apoptosis through caspase activation". Journal of Virology. 74 (7): 3105–11. doi:10.1128/jvi.74.7.3105-3111.2000. PMC 111809. PMID 10708425.

- Payne, Susan (2017). "Virus Interactions With the Cell". Viruses: 23-25. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-803109-4.00003-9. ISBN 9780128031094. S2CID 90650541. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Olson JK, Grose C (May 1997). "Endocytosis and recycling of varicella-zoster virus Fc receptor glycoprotein gE: internalization mediated by a YXXL motif in the cytoplasmic tail". Journal of Virology. 71 (5): 4042–54. doi:10.1128/JVI.71.5.4042-4054.1997. PMC 191557. PMID 9094682.

- Daniel J., DeNoon. "Genital Herpes' Silent Spread". WebMD. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- Esposito, Susanna; Daleno, Cristina; Baldanti, Fausto; Scala, Alessia; Campanini, Giulia; Taroni, Francesca (13 July 2011). "Viral shedding in children infected by pandemic A/H1N1/2009 influenza virus". Virology. 8. PMID 21752272. Retrieved 7 April 2020.