Giant virus

A giant virus, sometimes referred to as a girus, is a very large virus, some of which are larger than typical bacteria.[1][2] They have extremely large genomes compared to other viruses and contain many unique genes not found in life forms. All known giant viruses belong to the phylum Nucleocytoviricota.[3]

| Giant virus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mimivirus | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group I (dsDNA) |

| Phylum: | |

Description

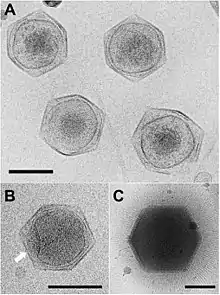

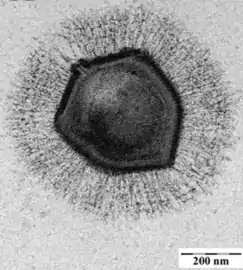

While the exact criteria as defined in the scientific literature vary, giant viruses are generally described as viruses having large, pseudo-icosahedral capsids (200 to 400 nanometers) that may be surrounded by a thick (approximately 100 nm) layer of filamentous protein fibers. The viruses' large, double-stranded DNA genomes (300 to 1000 kilobasepairs or larger) encode a large contingent of genes (of the order of 1000 genes).[3][4] While few giant viruses have been characterized in detail, the most notable examples are the phylogenetically related mimivirus and megavirus — both belonging to the Mimiviridae (aka Megaviridae) family, due to their having the largest capsid diameters of all known viruses.[3][4]

Giant viruses replicate within large spheroidal virus factories located within the cytoplasm of the infected host cell. This is similar to the replication mechanism used by Poxviridae, though whether this mechanism is employed by all giant viruses or only mimivirus and the related mamavirus has yet to be determined.[4] These virion replication factories can themselves be infected by the virophage satellite viruses, which inhibit or impair the reproduction of the complementary virus.

Giant viruses from the deep ocean, terrestrial sources, and human patients contain genes encoding cytochrome P450 (CYP; P450) enzymes. The origin of these P450 genes in giant viruses remains unknown but may have been acquired from an ancient host.[5]

Genetics and evolution

The genomes of giant viruses are the largest known for viruses, and contain genes that encode for important elements of translation machinery, a characteristic that had previously been believed to be indicative of cellular organisms. These genes include multiple genes encoding a number of aminoacyl tRNA synthetases, enzymes that catalyze the esterification of specific amino acids or their precursors to their corresponding cognate tRNAs to form an aminoacyl tRNA that is then used during translation.[4] The presence of four aminoacyl tRNA synthetase encoding genes in mimivirus and mamavirus genomes, both species within the Mimiviridae family, as well as the discovery of seven aminoacyl tRNA synthetase genes, including the four genes present in Mimiviridae, in the megavirus genome provide evidence for a possible scenario in which these large DNA viruses evolved from a shared ancestral cellular genome by means of genome reduction.[4]

Their discovery and subsequent characterization has triggered some debate concerning the evolutionary origins of giant viruses. The two main hypotheses for their origin are that either they evolved from small viruses, picking up DNA from host organisms, or that they evolved from very complicated organisms into the current form which is not self-sufficient for reproduction.[6] What sort of complicated organism giant viruses might have diverged from is also a topic of debate. One proposal is that the origin point actually represents a fourth domain of life,[4] but this has been largely discounted.[7][8]

Comparison of largest known giant viruses

| Giant virus name | Genome Length | Genes | Capsid diameter (nm) | Hair cover | Genbank # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bodo saltans virus[9] | 1,385,869 | 1227 proteins (predicted) | ~300 | yes (~40 nm) | MF782455 |

| Megavirus chilensis[10] | 1,259,197 | 1120 proteins (predicted) | 440 | yes (75 nm) | JN258408 |

| Mamavirus[11] | 1,191,693 | 1023 proteins (predicted) | 500 | yes (120 nm) | JF801956 |

| Mimivirus[12][13] | 1,181,549 | 979 proteins 39 non-coding | 500 | yes (120 nm) | NC_014649 |

| Tupanvirus[14] | 1,500,000 | 1276-1425 proteins | ≥450+550[15] | KY523104 MF405918[16] |

The whole list is in the Giant Virus Toplist created by the Giant Virus Finder software.[17]

| Giant virus name | Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase | Octocoral-like 1MutS | 2Stargate[18] | Known virophage[19] | Cytoplasmic virion factory | Host |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Megavirus chilensis | 7 (Tyr, Arg, Met, Cys, Trp, Asn, Ile) | yes | yes | no | yes | Acanthamoeba (Unikonta, Amoebozoa) |

| Mamavirus | 4 (Tyr, Arg, Met, Cys) | yes | yes | yes | yes | Acanthamoeba (Unikonta, Amoebozoa) |

| Mimivirus | 4 (Tyr, Arg, Met, Cys) | yes | yes | yes | yes | Acanthamoeba (Unikonta, Amoebozoa) |

1Mutator S (MutS) and its homologs are a family of DNA mismatch repair proteins involved in the mismatch repair system that acts to correct point mutations or small insertion/deletion loops produced during DNA replication, increasing the fidelity of replication. 2A stargate is a five-pronged star structure present on the viral capsid forming the portal through which the internal core of the particle is delivered to the host's cytoplasm.

See also

References

- Reynolds KA (2010). "Mysterious Microbe in Water Challenges the Very Definition of a Virus" (PDF). Water Conditioning & Purification. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-19.

- Ogata H, Toyoda K, Tomaru Y, Nakayama N, Shirai Y, Claverie JM, Nagasaki K (October 2009). "Remarkable sequence similarity between the dinoflagellate-infecting marine girus and the terrestrial pathogen African swine fever virus". Virology Journal. 6 (178): 178. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-6-178. PMC 2777158. PMID 19860921.

- Van Etten JL (July–August 2011). "Giant Viruses". American Scientist. 99 (4): 304–311. doi:10.1511/2011.91.304. Archived from the original on 2011-06-11.

- Legendre M, Arslan D, Abergel C, Claverie JM (January 2012). "Genomics of Megavirus and the elusive fourth domain of Life". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 5 (1): 102–6. doi:10.4161/cib.18624. PMC 3291303. PMID 22482024.

- Lamb DC, Follmer AH, Goldstone JV, Nelson DR, Warrilow AG, Price CL, et al. (June 2019). "On the occurrence of cytochrome P450 in viruses". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (25): 12343–12352. doi:10.1073/pnas.1901080116. PMC 6589655. PMID 31167942.

- Bichell RE. "In Giant Virus Genes, Hints About Their Mysterious Origin". All Things Considered.

- Schulz F, Yutin N, Ivanova NN, Ortega DR, Lee TK, Vierheilig J, Daims H, Horn M, Wagner M, Jensen GJ, Kyrpides NC, Koonin EV, Woyke T (April 2017). "Giant viruses with an expanded complement of translation system components" (PDF). Science. 356 (6333): 82–85. Bibcode:2017Sci...356...82S. doi:10.1126/science.aal4657. PMID 28386012. S2CID 206655792.

- Bäckström D, Yutin N, Jørgensen SL, Dharamshi J, Homa F, Zaremba-Niedwiedzka K, Spang A, Wolf YI, Koonin EV, Ettema TJ (March 2019). "Virus Genomes from Deep Sea Sediments Expand the Ocean Megavirome and Support Independent Origins of Viral Gigantism". mBio. 10 (2): e02497-02418. doi:10.1128/mBio.02497-18. PMC 6401483. PMID 30837339.

- Deeg CM, Chow CT, Suttle CA (March 2018). "The kinetoplastid-infecting Bodo saltans virus (BsV), a window into the most abundant giant viruses in the sea". eLife. 7: e33014. doi:10.7554/eLife.33014. PMC 5871332. PMID 29582753.

- Arslan D, Legendre M, Seltzer V, Abergel C, Claverie JM (October 2011). "Distant Mimivirus relative with a larger genome highlights the fundamental features of Megaviridae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (42): 17486–91. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10817486A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1110889108. PMC 3198346. PMID 21987820.

- Colson P, Yutin N, Shabalina SA, Robert C, Fournous G, La Scola B, Raoult D, Koonin EV (2011). "Viruses with more than 1,000 genes: Mamavirus, a new Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus strain, and reannotation of Mimivirus genes". Genome Biology and Evolution. 3: 737–42. doi:10.1093/gbe/evr048. PMC 3163472. PMID 21705471.

- Raoult D, Audic S, Robert C, Abergel C, Renesto P, Ogata H, La Scola B, Suzan M, Claverie JM (November 2004). "The 1.2-megabase genome sequence of Mimivirus". Science. 306 (5700): 1344–50. Bibcode:2004Sci...306.1344R. doi:10.1126/science.1101485. PMID 15486256. S2CID 84298461.

- Legendre M, Santini S, Rico A, Abergel C, Claverie JM (March 2011). "Breaking the 1000-gene barrier for Mimivirus using ultra-deep genome and transcriptome sequencing". Virology Journal. 8 (1): 99. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-8-99. PMC 3058096. PMID 21375749.

- Abrahão J, Silva L, Silva LS, Khalil JY, Rodrigues R, Arantes T, Assis F, Boratto P, Andrade M, Kroon EG, Ribeiro B, Bergier I, Seligmann H, Ghigo E, Colson P, Levasseur A, Kroemer G, Raoult D, La Scola B (February 2018). "Tailed giant Tupanvirus possesses the most complete translational apparatus of the known virosphere". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 749. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..749A. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03168-1. PMC 5829246. PMID 29487281.

- head and tail, respectively

- soda lake and deep ocean species of Tupanvirues, respectively

- "Giant Virus Toplist". PIT Bioinformatics Group, Department of Computer Science. Eötvös University. 2015-03-26.

- Zauberman N, Mutsafi Y, Halevy DB, Shimoni E, Klein E, Xiao C, Sun S, Minsky A (May 2008). Sugden B (ed.). "Distinct DNA exit and packaging portals in the virus Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus". PLOS Biology. 6 (5): e114. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060114. PMC 2430901. PMID 18479185.

- Fischer MG, Suttle CA (April 2011). "A virophage at the origin of large DNA transposons". Science. 332 (6026): 231–4. Bibcode:2011Sci...332..231F. doi:10.1126/science.1199412. PMID 21385722. S2CID 206530677.

External links

Media related to Giant viruses at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Giant viruses at Wikimedia Commons