Wadsworth Jarrell

Wadsworth Aikens Jarrell (born November 20, 1929) is an American painter, sculptor and printmaker. He was born in Albany, Georgia, and moved to Chicago, Illinois, where he attended the Art Institute of Chicago. After graduation, he became heavily involved in the local art scene and through his early work he explored the working life of blacks in Chicago and found influence in the sights and sounds of jazz music. In the late 1960s he opened WJ Studio and Gallery, where he, along with his wife, Jae, hosted regional artists and musicians.

Wadsworth Jarrell | |

|---|---|

| Born | Wadsworth Aikens Jarrell November 20, 1929 Albany, Georgia, U.S. |

| Education | Art Institute of Chicago, Howard University |

| Spouse(s) | Jae Jarrell |

| Patron(s) | Murry N. DePillars |

Mid-1960s Chicago saw a rise in racial violence leading to the examination of race relations and black empowerment by local artists. Jarrell became involved in the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), a group that would serve as a launching pad for the era's black art movement. In 1967, OBAC artists created the Wall of Respect, a mural in Chicago that depicted African American heroes and is credited with triggering the political mural movement in Chicago and beyond. In 1969, Jarrell co-founded AFRICOBRA: African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists. AFRICOBRA would become internationally acclaimed for their politically themed art and use of "coolade colors" in their paintings.

Jarrell's career took him to Africa in 1977, where he found inspiration in the Senufo people of Ivory Coast, Mali and Burkina Faso. Upon return to the United States he moved to Georgia and taught at the University of Georgia. In Georgia, he began to use a bricklayer's trowel on his canvases, creating a textured appearance within his already visually active paintings. The figures often seen in his paintings are abstract and inspired by the masks and sculptures of Nigeria. These Nigerian arts have also inspired Jarrell's totem sculptures. Living and working in Cleveland, Jarrell continues to explore the contemporary African American experience through his paintings, sculptures, and prints. His work is found in the collections of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, High Museum of Art, The Studio Museum in Harlem and the University of Delaware.

Personal life

Early life

Jarrell was born in Albany, Georgia, in 1929 to Solomon Marcus and Tabitha Jarrell. Named after the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,[1] he was the youngest of six children.[2] A year after Jarrell's birth the family moved to a 28-acre farm near Athens, Georgia, where they grew vegetables and cotton.[1] Jarrell's father was a carpenter and furniture maker who had his own business, the S.M. Jarrell Furniture Store.[3] All three Jarrell boys worked there, one of them learning to cane chairs.[1] Their father's artistic ability and mother's skill as a quilt-maker contributed to the entire family's love for art.[4] As a child, Jarrell first attended a one-room schoolhouse[5] where he was encouraged by his teacher, Jessie Lois Hall, to explore his artistic side.[3] He then went to a private Baptist school starting in the seventh grade before transferring to Athens High in the tenth grade. In high school his talent for art was apparent as he started creating his own comic strip, cartoons for the school paper, and illustrations for sports events, finally taking up oil painting. As a young man interested in art during the late 1930s and early 1940s he learned about painting and illustration through magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post and Collier's. Unable to figure out the distinction between illustration and painting, Jarrell thought "artists eventually got rich – but it was illustrators making the large sums of money."[6]

Jarrell's relationship with his mother became closer once his father and one of his brothers left to work at a shipyard during World War II.[1] His father died of malaria while working there.[7] While in high school, Jarrell helped his mother tend the farm, but did not like the work.[1] After graduating from high school, he joined the Army, was stationed at Fort Polk, Louisiana and served briefly in Korea. At Fort Polk he became company artist and made extra money designing shirts and making paintings for fellow soldiers.[8]

Higher education and current life

After military service, Jarrell moved to Chicago where his sister Nellie attended Northwestern University. It was in Chicago where Jarrell would have his first museum experiences. Growing in up Georgia, African Americans were not allowed to visit museums until the Civil Rights Act of 1964, therefore these early museum visits made a major impression on him.[8] A year later he enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago for advertising art and graphic design, where he attended night classes. His days were spent working at the International Paint company where he mixed paint. He also took classes at the Ray Vogue School for Commercial Arts. He began attending the Art Institute full-time in 1954. Jarrell eventually lost interest in commercial art and focused on classes about painting and drawing, gaining inspiration from instructor Laura McKinnon and her ideas about spatial relationship theory. In 1958, he graduated with his original major(s), retaining a strong desire to pursue the life of a fine artist. At this time he also met artist Jeff Donaldson, who became a friend who influenced his career. In 1959, the year of his first marriage, he became an advertising photographer, taking photos of type and lettering styles. The couple would divorce shortly after the marriage.[9]

In 1963, Jarrell met Elaine Annette Johnson, known as Jae, who ran a clothing boutique,[10] the woman who became his second wife on June 2, 1967.[11] They spent their honeymoon in Nassau[11] and on January 7, 1968, Wadsworth Jr. was born. During the pregnancy Jae closed her boutique and moved into Jarrell's studio, running a mail order service instead.[12] As the social and economic world of Chicago declined, gang violence threatened the family's neighborhood. After their second child, Jennifer, was born the family decided to move to the New York City area.[13] In May 1971, they made the move, first heading to Waterbury, Connecticut, then New Haven before spending three months in Boston. The family then moved to Washington, D.C. where Jarrell began teaching at Howard University in 1971, recruited by Jeff Donaldson.[14] At Howard he pursued his MFA, focusing on African culture, specifically the Senufo people.[15] The couple would have another daughter, Roslyn Angela, in 1972. S

Struggling to fit in at Howard, unable to make tenure,[16] and with concerns about the increasing crime rates in Washington, the family decided to move once again in 1977,[17] this time to Athens, Georgia.[17] Shortly after the move Jarrell became an assistant professor at the University of Georgia. He and his wife started a high-end educational toy company that stemmed from their children's love for similar toys when living in Washington, D.C.[18] They opened a small shop called Tadpole Toys and Hobby Center in Athens to great reception. However, as a result of poor sales in May 1982 they were forced to close it. Soon afterwards, Jarrell received tenure at the University.[19] In 1988, he retired from his position and from teaching as a whole in order to focus on his creative work.[4] By 1994 all three children were grown; the two daughters attended the Art Institute of Chicago, and Wadsworth Jr. became a seafarer. That year, Jae and daughter Jennifer moved to New York to find a place to live, settling in SoHo, where they were joined by Jarrell a few months later.[20] Currently, Jarrell and Jae live and work in Cleveland, Ohio.[21]

Artistic career

Every year you are reminded of George Washington's birthday ... my kids learn about this at school, but nothing is said about black heroes. If white Americans can engage in what I call repetitious advertising, then I feel justified in advertising for black Americans.

— Wadsworth Jarrell, 1978[22]

Chicago

After graduation from the Art Institute, Jarrell lived off his wages from mixing paint and furthered his skills in his studio for a year. He started to submit his work to competitions, being accepted at the Chicago Show at the Navy Pier and the Union League Show. Jarrell produced artworks inspired by theories learned in school and scenes of everyday life in black Chicago. With an interest in horse racing, jazz clubs and bars, he often took a sketchpad on his explorations, eventually creating paintings like Neon Row (1958), a street scene, Shamrock Inn (1962), a bar scene, and The Jockeys #1 (1962), from a visit to a horse racing track.[9] These themes would recur throughout his career. His early works display the "two-dimensional illusionism" he learned in school: linear and geometric perspective with overlapping objects receding to a vanishing point on the horizon. Color is used to depict movement and stability, a contrast seen in Shamrock Inn and The Jockeys #1, however, Jarrell's palette had evolved into brighter and bolder color combinations, at times contrasting in their final execution. The influence of post-impressionism is evident in these earlier works, in line with art education trends at the time.[23]

A notable turning point for his career came in 1963 when a watercolor (similar to Jazz Giants #1 (1962)) was accepted for the Art Institute's "2nd Biennial Drawing, Watercolor and Print Exhibition." The exhibit earned him prizes, media attention, and the opportunity to exhibit his work at other galleries throughout the Midwest. He moved to a large studio in the Hyde Park neighborhood and continued expanding on his work and focusing on musical and sport related themes.[23] His pigment application became rapid, whether he was depicting a jazz musician or a jockey on his horse, allowing the image to express strong movement. Cockfight (1965) shows the evolution of Jarrell's work: intense color bands, swirls, and at times a psychedelic appearance to the bird in focus, a style that became a mainstay in his work.[24]

Influenced by his honeymoon in the Caribbean, Jarrell became interested in the effects of man-made and natural sunlight on the environment. Experimentation with pigments, media, imagery and design allowed him to create artworks that fully expressed his intended messages. Referring to works such as Nassau (1968) and Sign of the Times (1966), Jarrell commented: "The colors of the Bahamas influenced my use of color and my approach to my work." With Sign of the Times he shows a street scene, his first attempt at a painting involving social interaction.[11] In 1968, Jarrell became art director at Sander Line Graphics, only to quit shortly thereafter to become self-employed. Aside from creating his art he also started a successful mail-order photo processing business. Soon after Jarrell and Jae decided to open a gallery space below their studio: WJ Studio and Gallery.[12] While the studio and gallery flourished, Jarrell taught part-time art classes at Wadsworth Elementary School and considered moving to New York, seeking refuge in the heart of the art world.[25]

Wall of Respect

In 1964 Chicago experienced two major race riots. Triggered by Civil Rights struggles and angst, more riots followed in subsequent years and the Black Power movement came into fruition. Artists began to explore ways to express black pride, self-determination and self-reliance leading in 1966 to the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC).[10] Artist Norman Parish asked Jarrell to attend a meeting for OBAC's Artists' Workshop. The meetings would consist of artists bringing their work to be critiqued and reflect on ideas of the black experience in art, leading to the concept behind Wall of Respect. The mural consisted of African American heroes and personalities, each artist deciding who should be depicted in their section. Sylvia Abernathy designed the layout, giving Jarrell a 12 × 14-foot space to share with photographer Bill Abernathy.[26] Jarrell focused on a favorite theme, rhythm and blues, and featured portrayals of James Brown, B.B. King, Billie Holiday, Muddy Waters, Aretha Franklin and Dinah Washington. The Artists' Workshop would sour towards the end of the project: there were controversies stemming from the painting in Norman Parish's section, conflicts regarding copyrights being sold without permission, disagreements on law enforcement involvement, as well as deceit. Nevertheless, the Wall was considered a success, triggering the creation of liberation themed murals in Chicago and beyond.[11]

WJ Studio and Gallery

In 1968, Jarrell and his wife opened WJ Studio and Gallery, below their home and studio.[12] The space not only showcased the couple's work and that of other artists but went on to display the talents of Chicago poets and musicians. Jarrell's love for blues and jazz music made it easy for him to access the city's talent and his involvement with OCAC provided him with contacts in the poetry world. Artists such as Muhal Richard Abrams, John Stubblefield, Henry Threadgill, Anthony Braxton and the Chicago Art Ensemble would perform at the space.[27] The gallery also served as a gathering place for the likes of Jeff Donaldson, Barbara Jones-Hogu, Gerald Williams and others, who would come to discuss concepts of a relevant black art aesthetic. The group struggled: Jarrell described the search as an attempt to find "a collective concept that would say 'black art' at a glance."[28] Eventually, the group made a breakthrough while listing principles and ideas regarding the concept of black art; the term "coolade colors" was contributed by a fabric designer. The term covered the bright fashion of stylish African American men of the time, which Jarrell described as "loud lime, pimp yellows, hot pinks, high-key color clothing." The final concept for their aesthetic search would be message oriented art, revolving around socially aware content. African design would be included and meaningfulness for black people would be a necessity. This group's formation would be considered one of the best aligned and organized collectives in the Black Arts Movement. This group went on to form COBRA.[29]

COBRA and the black aesthetic

Like many African American grass roots organizations, Jarrell's gallery group struggled to carry the torch after the deaths of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. Jarrell and his fellow Chicago artists took the path of non-violence by way of their artistic talents and a sense of ownership through their contributions at WJ Studio and Gallery. With these ideals backing them and their new aesthetic philosophy, the group took on the name COBRA – Coalition of Black Revolutionary Artists.[29] With the creation of COBRA, Jarrell completed his first work that conceptualized the concept behind the group, Black Family (1969), which utilized the color scheme of the coolade colors such as light blue and orange contrasting with white areas, which heightened the bright colors' intensity. This technique allowed Jarrell to create what he described as an "intuitive space," drawing the viewer's attention towards the family on the canvas: a caring mother, protective father and two relaxed children. With a father depicting strength and honesty, and what Robert Douglas describes as a "heroic quality," to the painting, Jarrell expresses important aspects of the COBRA ideal. Writing also appears on the canvas, with the word "blackness" represented by the letter B. The group decided to go from focusing on themed exhibitions to encouraging artworks that "portray the general problems of black people or attempt to visualize some solutions to them."[30]

AFRICOBRA's beginnings

AFRICOBRA artists are visual griots of the African American community, an imagery that illuminates the beauty and glory of the Africans' experience in the West. They present to us an iconography bestowed on them by the pressing and always exciting culture of the African American.

In 1969, COBRA revised their philosophy and artistic concept to expand their concern for black liberation and civil rights on an international level. Inspired by the words of Malcolm X, "All black people, regardless of their land base, have the same problems, the control of their land and economics by Europeans or Euro-Americans.", they changed their name to AfriCOBRA: African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists.[30] Jarrell's work had evolved to bring the focus figure to the foreground of his paintings, as seen in Coolade Lester (1970), a portrait of musician Lester Lashley. Letters make another appearance: D (down), B (black), F (fine) and Q (question). The work is described as a "humanistic portrayal of the genius of Africans in the creation of jazz." Other works by Jarrell at the time became politically and socially charged with the aesthetics put forth by AfriCOBRA. Homage to a Giant (1970) is Jarrell's first tribute to Malcolm X. This work is used by Jarrell to speak for the black struggle against oppression and the death of student protestors fighting for that cause.[32] Four images of Malcolm X are painted alongside those of Huey Newton, Jesse Jackson and Stokley Carmichael. "B" makes its usual appearance representing "blackness" and "badness" as well as a quote from Ossie Davis's eulogy at Malcolm's funeral. This piece, along with Coolade Lester, appeared in AFRI-COBRA's first exhibition in 1970 at the Studio Museum in Harlem: "AFRI-COBRA I: Ten in Search of a Nation." The response to the show was one of misunderstanding by many viewers, with the result that the concepts presented were interpreted as "protest art."[33]

"AFRICOBRA II" was held in 1971 at the Studio Museum in Harlem before it traveled to five other museums and galleries. Jarrell exhibited Revolutionary and Black Prince (both 1971) at the show. These two portraits are described by art historian Robert Douglas as displaying "Jarrell's masterful understanding of portraiture, rendered through a chiaroscuro technique employing a multitude of meticulously painted B's in different sizes and coolade hues." Revolutionary is a homage to Angela Davis. She wears a Revolutionary Suit that was designed by Jae Jarrell for the AFRICOBRA II exhibition. Prints were made of the work. However, in the original, the cartridge belt is attached to the canvas, an idea of Jae's. The words "love", "black", "nation", "time", "rest", "full of shit", "revolution", and "beautiful" burst out of her head on the canvas. The message "I have given my life in the struggle. If I have to lose my life, that is the way it will be," travels down her chest and left arm. "B", as usual, represents "blackness" "bad" and in this painting "beautiful". The work epitomizes the goal by AFRICOBRA artists to use all space possible in their creations, described as "jam-packed and jelly tight."[33] Revolutionary was reviewed by Nancy Tobin Willig as "a portrait of a young black woman screaming slogans – with a bandoleer loaded with real bullets slung over her shoulder. Jarrell's painting is an overstatement. It is not art as the weapon. It is the weapon as art."[34] Black Prince is Jarrell's second tribute to Malcolm X. "B" appears in the painting, as well as "P"; "PRINCE" and "BLACK" which travel throughout Malcolm's face and hand. The quote "I believe in anything necessary to correct unjust conditions, political, economic, social, physical. Anything necessary as long as it gets results," is painted across his chest and arm.[33] Their second show, "AFRICOBRA III", opened in 1973. Critics were more aware of the aesthetic and movement at this show; critic Paul Richard commented that the works of Nelson Stevens, Jeff Donaldson and Jarrell "together contradict something I have long believed: that art that is so blatantly political is not art at all."[34]

Out east

Despite the offers for a position he received from Jeff Donaldson, who was running Howard University's art department, Jarrell sought to remain independent and the family moved to New York.[13] Jarrell obtained work as a photographer in Boston, eventually choosing to accept Donaldson's offer, moving the family in time for Jarrell to teach photography classes during the fall semester.[14] During this time "AFRICOBRA II" traveled to Howard and Jarrell exhibited Together We Will Win (1973), showing black "warriors," children, women and workers "offering solutions to African people's problems," and Liberation Soldiers, (1972), depicting the Black Panthers. Both works included the use of aluminum and gold foil glued to the canvas.[34] In 1973 the final AFRICOBRA show, "AFRICOBRA III" was held. However, members still continued to meet and practice the ideals put forward by the group.[15]

African influences

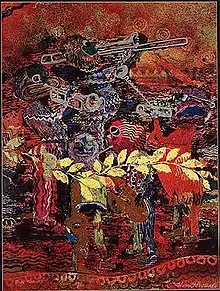

Jarrell's studies of African art and the Senufo people appeared as a major influence during the mid-1970s. Paintings such as Prophecy, Reorientation and Navaga depict human figures that appear blended with Senufo sculptures. Navaga (1974) shows a seated woodcarver, holding a staff he works on, appearing to be made of wood himself. He wears clothing of and is surrounded by coolade colors. The face is that of Jarrell's father, manipulated into a Senufo sculptural style. In the triptych Prophecy Jarrell shows African women as Senufo figures holding sculptures of the Yoruba deity Shango, and is described as "jam-packed"[35] with imagery, making it hard to decipher in a short time.[36]

In winter of 1977 Jarrell and Jae visited Lagos, Nigeria, as part of the American delegation to FESTAC '77, the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, making this the couple's first international exhibition. Other AFRICOBRA members journeyed there as well. Jarrell was influenced heavily by the bronze lost-wax castings of Benin and the woodcarving and textile arts of Oshogbo, which he believed solidified the mission of AFRI-COBRA's symbolic work through "intuitive space." Jarrell also revisited his passion for horse racing, attending the Grand Durbar in Kaduna. On Jarrell's return, AFRI-COBRA formed their next show "AFRI-COBRA/Farafindugu"; farafindugu inferring "black world" in Mandinka.[37]

The exhibit, at the African American Museum in Philadelphia, featured two works by Jarrell created as a response to his journey to Africa: Mojo Workin and Soweto (both 1977). Mojo Workin featured a contribution from his then six-year-old eldest daughter, Jennifer.[38] She created the drawing The Magic Lady and with Jarrell's painting it was believed that mojo was expressed when others encountered the work. This is one of the first times Jarrell uses a stained canvas. Soweto reflects the struggles of African people, specifically those suffering from the apartheid in South Africa.[39] The painting is named after the city of Soweto, where a massacre of students occurred in 1976.[17] Continuing to be inspired by his travels to Nigeria, Jarrell completed the work Zulu Sunday which was created to express similarities between African Americans and Nigerians through a celebration of a Sunday afternoon social affair. The painting shows Zulus dressed in ornate traditional dress, socializing on the street, unified by a sunburst.[40]

Georgia

In 1977 the Jarrells moved from Washington, D.C. to Athens, Georgia. With his children getting older and the couple's toy company struggling to stay afloat, Jarrell became assistant professor at the University of Georgia.[18] His position at the university assured him studio space. In 1979 he had two solo shows and participated in three AFRICOBRA exhibitions. His work continued to be socially and politically aware with paintings like Festival #1 (1978) showing brilliant Senufo figures, a work supporting South Africans at war. African imagery became more apparent in his paintings with zigzag patterns and lizards appearing, representing "that Africans, as the first people, have the right to speak on their own behalf," as seen in Midnight Poet at 125th Street & Lenox (1979). In 1979 Jarrell received grant money to create a 52 x 31-foot mural at the East Athens Community Center. A team of art students helped Jarrell and Jae to complete the work, titled Ascension, which remains in Athens today.[22]

By the mid-1980s Jarrell was being represented by the Fay Gold Gallery in Atlanta. In 1984 the family moved to Atlanta when Jae accepted a teaching position at The Lovett School. Jarrell continued to commute to Athens to teach. The move to Atlanta provided more income for the family while allowing Jarrell to sell more work and spark relationships with potential customers, galleries and museums in the region.[19] Jarrell became the painting professor for the University's Studies Abroad Program in 1986. For two months he lived in Cortona, Italy with Jae and his two daughters, while Wadsworth Jr. remained in Atlanta finishing high school. The opportunity allowed him to explore the country, visiting historic sites throughout Italy and the Venice Biennale.[41] Upon his return he was promoted to full professor at the university in February 1987, but he resigned in 1988.[42]

During the 1990s Jarrell continued to explore aspects of black life in his paintings. Dudes on the Street (1991) is a depiction of black life in the city; two cartoon-like men and two women stand on the street with an expired parking meter next to them. The background features a ribs restaurant and a record shop, with coolade colors drenching the entire landscape. Robert Douglas compared the piece to Chicken Shack by Archibald Motley, stating "both artists have fulfilled the mission of celebrating black life." Two paintings about boxing were created during this time as well: Stride of a Legend/Tribute to Papa Tall, a tribute to Muhammad Ali and textile designer Papa Tall of Senegal, and The Champion (1991) a portrayal Evander Holyfield.[43]

Horse racing revisited

While in Georgia Jarrell revisited his interest in horse racing. He became interested in African American jockeys, creating the paintings The Jocks #2 (1981) and Master Tester (1981) and Homage to Isaac Murphy (1981). The Jocks #2 is a group portrait of James "Soup" Perkins, William Walker, Jimmy Winkfield and Isaac Murphy. The figures appear like a Kemetic wall painting with hints of green and light blue. At the center is Isaac Murphy, a legendary jockey of the Kentucky Derby, wearing a glowing crown. A full tribute to Murphy is seen in Homage to Isaac Murphy, a large polyptych consisting of four canvasses. Cut out leaf motifs are adhered to the canvas and applied with acrylic stains, which make the motif's appear as negative space on the surface of the painting. Zigzags are prominent, a lizard appears to represent speed, a lawn jockey, and the dates of Murphy's wins, titles and horse names are at the top. The painting is finished with a stylized portrait of Murphy and cowry shells are glued to the canvas representing the money won by Murphy during his career. Master Tester is an abstract of horse trainer Marshall Lilly, riding a horse, wearing a derby hat.[44] In 1993 Jarrell would have a solo show, titled "Edge Cutters," at the Kentucky Derby Museum in Lexington, Kentucky.[43]

The bricklayer's trowel and jazz tributes

In December 1982 Jarrell was commissioned by Westinghouse Electric Company to create a three-hundred-foot mural in their Athens headquarters, to boost the morale of the employees. The mural was the first time he used a bricklayer's trowel in his work, a tool introduced to him by Adger Cowans. The Apple Birds and The Return of the Apple Birds, from 1983, show his dramatic use of the trowel. The paintings were inspired by a drawing by his daughter, Jennifer, at the age of two. The Apple Birds were drawn by and talked about by Jennifer as having apple-shaped heads with stems at the top, long arms and short bodies. Zigzags, geometric shapes and layers make up the environment that the Apple Birds live in on the canvas. The trowel is used throughout to create 3-D layers and overlaps.[44]

Jarrell created many jazz tributes starting in the 1980s. Cookin' n Smokin' (1986) is a tribute to jazz musician Oscar Peterson, who is shown playing piano with a sunburst design around his head. To the left of Peterson is bass player Ray Brown. Both figures have large heads, their faces have exaggerated features similar to African masks, and are described as being "midpoint between naturalism and abstraction" by Robert Douglas. The trowel is used throughout to blend color.[41] Jazz Giants (1987), another jazz tribute, shows Dizzy Gillespie, Harry Carney, Johnny Hodges and Cootie Williams performing. Leaf patterns and circles common in Jarrell's work are seen throughout. The trowel is used to create recognizable portraits of the musicians, with the paint on a white background appearing as if a woodcut. Priestess (1988) depicts another jazz icon, Nina Simone, who appears twice – playing piano and singing solo, backed by a band.[42] 1979's I Remember Bill is a memorial to Jarrell's friend guitarist Bill Harris, originally of The Clovers.[43][45] Jarrell occasionally traveled with Harris, hanging his paintings behind Harris as he performed. The painting is a large mixed-media polyptych of shaped canvas, and a painted six-stringed guitar sits on the top of the work. The painting features glued on photographs of Harris and two painted portraits of the musician, surrounded by Jarrell's signature symbols, designs and patterns.[45]

Other works include: Corners of Jazz (1988), a large mural featuring Ray Charles, Lester Young, and Billie Holiday, Shon'nuf (1989), featuring Ray Charles, At the Three Deuces (1991) with Miles Davis, Charlie Parker and Sam Potter, Basie at the Apollo (1992) with Count Basie's orchestra, The Empress (1992) for Bessie Smith, and Lady & Prez #2, showing Holiday and Young performing together.[46]

Sculpture

Inspired by his trip to Italy, Jarrell created the sculpture Tribute to Ovambo Bellows, a conical-shaped painted tribute to the Ovambo people, which would be the basis for a new shift in his work, towards sculpture.[42] The new works would be categorized by their heavy spiritual nature, reflective of African culture and heritage. Hausa Space – a Village (1993) represents the villages Jarrell visited in Nigeria. The houses that he saw were decorated with icons and symbols of spiritual and ritual meaning, painted in bright colors. These decorations are used to fight evil spirits, while Jarrell's pieces speak for peace.[47] Many of the sculptures blend elements of African art and design; Sorcerer (1993) and Messenger of Information (1993) show his earlier influences from Senufo art and other inspirations related to the design, spirituality and people of Africa.[48] Totem–like sculptures began to be created in 1995. The three sculptures making up the Ensemble series (1995) each stand over five feet tall and are painted with brilliant colors, topped off with a small animal. For the first time, in Days of the Kings (1995), horse racing appears in Jarrell's sculptures. Sixteen totems serve as tributes to African Americans in horse racing, reminiscent of the designs of the Bijogo and Alberto Giacometti.[20] Epiphany (1996) memorializes the Million Man March, held in Washington, D.C. the previous year, an event that Jarrell described as one of the most important of that century. This piece, and other works, were later exhibited at the 1996 Summer Olympics.[49]

Reception

Dr. Stacy Morgan, association professor in the department of American Studies at the University of Alabama, describes Jarrell's work as "a remarkable body of vibrant, stylistically innovative and politically engaged art."[21]

Awards

- First prize, 1988, Atlanta Life Invitational Exhibition, Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art[42]

- Cover, 1985, Art Papers

- Excellence in painting award, 1985, Southern Home Shows Exposition[50]

- Award, 1974, District of Columbia Commission on the Arts

- Artist-in-Residence, 1974, District of Columbia Public Schools[15]

Selected exhibitions

Solo exhibitions

- Edge Cutters. 1993, Kentucky Derby Museum.

- Large Format. 1987, Southwest Atlanta Hospital.

- Paintings and Sculptures, Wadsworth Jarrell. 1987, Albany Museum of Art.

- The Power and the Glory. 1979, University of Georgia.

- Going Home., 1976, Howard University.

Group exhibitions

- AFRI-COBRA: No Middle Ground. 1992, Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago, Illinois.

- Twelfth Annual Atlanta Life Invitational Exhibition. 1992, Herndon Plaza, Atlanta.

- Vital Signs. 1991, Atlanta Contemporary Art Center.

- AFRI-COBRA: The First Twenty Years. 1990, Florida A&M University.

- Horse Flesh. 1990, Kentucky Derby Museum.

- Beaches Annual Exhibition. 1989, Museum of Contemporary Art Jacksonville.

- Artists in Georgia 1988., 1988 Atlanta Contemporary Art Center.

- The Art in Atlanta. 1988, Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art.

- Birmingham Biennial. 1987, Birmingham Museum of Art.

- AFRICOBRA USA. 1987, Sermac Gallery, Fort-de-France, Martinique.

- Ot Och In. 1986, Malmö konstmuseum.

- Artists in Georgia. 1985, Georgia Museum of Art.

- Atlanta in France. 1985, Chapelle de la Sorbonne.

- U.S.A. Volta Del Sud. 1985, Palazzo Venezia.

- Commemoration to Soweto. AFRI-COBRA, 1980, United Nations Headquarters.

- Directions and Dimensions. 1980, Mississippi Museum of Natural Science.

- Artists in Georgia. 1980, High Museum of Art.

- Artists in Schools. 1976, Delaware Art Museum.

- Directions in Afro-American Art. 1974, Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art.[51]

Selected collections

See also

References

- Julieanna Richardson (2001). "Wadsworth Jarrell recalls growing up on a farm in Oconee County, Georgia". HistoryMakers Digital Archive. The HistoryMakers. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Douglas, 1.

- Douglas, 2.

- Julieanna L. Richardson (2001). "The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Wadsworth Jarrell". Programs. The HistoryMakers. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Julieanna Richardson (2001). "Wadsworth Jarrell talks about his school years in Georgia". HistoryMakers Digital Archive. The HistoryMakers. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Douglas, 2–3.

- Julieanna Richardson (2001). "Wadsworth Jarrell reflects on the impact of his father's death on the family". HistoryMakers Digital Archive. The HistoryMakers. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Douglas, 5.

- Douglas, 7.

- Douglas, 19.

- Douglas, 22.

- Douglas, 24.

- Douglas, 36.

- Douglas, 39.

- Douglas, 42.

- Julieanna Richardson (2001). "Wadsworth Jarrell describes his experiences teaching at Howard University and tells why he left". HistoryMakers Digital Archive. The HistoryMakers. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Douglas, 50.

- Douglas, 53.

- Douglas, 64.

- Douglas, 91.

- "Paul R. Jones Lecture Series Continues at University of Alabama with Artist Wadsworth Jarrell". U.S. Federal News Service. October 7, 2010. ProQuest 756830550.

- Douglas, 56.

- Douglas, 9.

- Douglas, 10.

- Douglas, 35.

- Douglas, 20.

- Douglas, 25.

- Douglas, 26.

- Douglas, 29.

- Douglas, 30.

- Douglas, 71.

- Douglas, 32.

- Douglas, 34.

- Douglas, 40.

- Douglas, 46.

- Douglas, 44.

- L. Ellsworth, Kirstin (August 31, 2009). "Africobra and the Negotiation of Visual Afrocentrisms". Civilisations. Revue internationale d'anthropologie et de sciences humaines (in French) (58–1): 21–38. doi:10.4000/civilisations.1890. ISSN 0009-8140.

- Douglas, 48.

- Douglas, 49.

- Douglas, 58.

- Douglas, 66.

- Douglas, 68.

- Douglas, 80.

- Douglas, 60.

- Douglas, 79.

- Douglas, 72, 75.

- Douglas, 85.

- Douglas, 89.

- Douglas, 94.

- Douglas, 65.

- Douglas, 107.

Further reading

- Donaldson, Jeff. "Africobra 1 (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists): '10 in Search of a Nation'", Black World XIX, no. 12 (October 1970): 89–89.

- Douglas, Robert L. Wadsworth Jarrell: The Artist as Revolutionary. Rohnert Park, California: Pomegranate, 1996. ISBN 0-7649-0012-9

- Dyke, Kristina Van. "Wadsworth Jarrell: City Gallery East, Atlanta; exhibit." Art Papers 20 (November/December 1996): 31–32.

- Harris, Juliette. "AFRICOBRA NOW!" The International Review of African American Art. 21 (2) (2007): 2–11. Hampton University Museum.

External links

- Interviews of AfriCOBRA founders, 2010 from the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- Wadsworth Jarrell at africobra.com (archived)

- "Wadsworth and Jae Jarrell", Never The Same

- "Wadsworth Jarrell, Sr.", History Makers