West Slavic languages

The West Slavic languages are a subdivision of the Slavic language group. They include Polish, Czech, Slovak, Kashubian, Upper Sorbian and Lower Sorbian. The languages are spoken across a continuous region encompassing the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland as well as the former East Germany and the westernmost regions of Ukraine and Belarus (and into Lithuania).

| West Slavic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Central Europe |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-5 | zlw |

| Glottolog | west2792 |

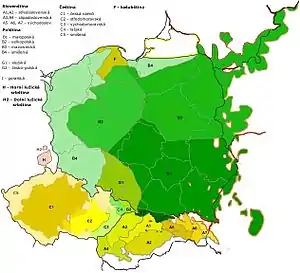

Distribution of the West Slavic languages.

Polish

Kashubian

Silesian

Polabian †

Lower Sorbian

Upper Sorbian

Czech

Slovak | |

Classification

West Slavic is usually divided into three subgroups based on similarity and degree of mutual intelligibility, Czecho-Slovak, Lechitic and Sorbian, as follows:[1]

| West Slavic |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Distinctive features

Some distinctive features of the West Slavic languages, as from when they split from the East Slavic and South Slavic branches around the 3rd to 6th centuries AD, are as follows:[2]

- development of proto-Slavic tj, dj into palatalized ts, (d)z, as in modern Polish/Czech/Slovak noc ("night"; compare Russian ночь);

- retention of the groups kv, gv as in Polish gwiazda ("star"; compare Russian звезда; but note also Russian цвет vs. Ukrainian квіт, "flower");

- retention of tl, dl, as in Polish/Slovak/Czech radlo/rádlo ("ard"; compare Russian рало);

- palatized h developed into š, as in Polish musze (locative case of mucha, "fly");

- the groups pj, bj, mj, vj developed into (soft) consonant forms without the epenthesis of l, as in Polish kupię ("I shall buy"; compare Russian куплю);

- a tendency towards fixed stress (on the first or penultimate syllable);

- use of the endings -ego/-ého for the genitive singular of the adjectival declension;

- use of the pronoun form tъnъ rather than tъ, leading to Slovak/Polish/Czech ten ("this" (masc.); compare Russian тот);

- extension of the genitive form čьso to nominative and accusative in place of čь(to), leading to Polish/Czech co ("what", compare Russian что).

The West Slavic languages are all written using Latin script, in contrast to the Cyrillic-using East Slavic branch, and the South Slavic which uses both.

History

The early Slavic expansion reached Central Europe in c. the 7th century, and the West Slavic dialects diverged from Common Slavic over the following centuries. West Slavic polities of the 9th century include the Principality of Nitra and Great Moravia. The West Slavic tribes settled on the eastern fringes of the Carolingian Empire, along the Limes Saxoniae. The Obotrites were given territories by Charlemagne in exchange for their support in his war against the Saxons.

In the high medieval period, the West Slavic tribes were again pushed to the east by the incipient German Ostsiedlung, decisively so following the Wendish Crusade in the 11th century. The Sorbs and other Polabian Slavs like Obodrites and Veleti came under the domination of the Holy Roman Empire and were strongly Germanized.[3]

The central Polish tribe of the Polans established their own state – the Duchy of Poland – in the 10th century under Duke Mieszko I; this later became a kingdom in 1025 (see: Kingdom of Poland (1025–1385)). While still a duke, Bolesław I the Brave had been declared by Holy Roman Emperor Otto III as Frater et Cooperator Imperii ("Brother and Partner of the Empire") implying that at that point Poland was at least nominally considered a foederatus of the Holy Roman Empire.[4]

The Bohemians established the Duchy of Bohemia in the 9th century, which was incorporated into the Holy Roman Empire in the early 11th century. At the end of the 12th century the duchy was raised to the status of kingdom, which was legally recognised in 1212 in the Golden Bull of Sicily. Lusatia, the homeland of the remaining Sorbs, became a crown land of Bohemia in the 11th century, and Silesia followed suit in 1335. The Slovaks, on the other hand, never became part of the Holy Roman Empire, being incorporated into the Kingdom of Hungary. Hungary fell under Habsburg rule alongside Austria and Bohemia in the 16th century, thus uniting the Bohemians, Moravians, Slovaks, and Silesians under a single ruler. While Lusatia was lost to Saxony in 1635 and most of Silesia was lost to Prussia in 1740, the remaining West Slavic Habsburg dominions remained part of the Austrian Empire and then Austria-Hungary, and after that remained united until 1992 in the form of Czechoslovakia.

Over the past century, there have been efforts by some to standardize and to recognize Silesian, Lachian, and Moravian as separate languages.

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to West Slavic languages. |

- Blažek, Václav. "On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: Survey" (PDF). pp. 16–17.

- Zenon Klemensiewicz, Historia języka Polskiego, 7th edition, Wydawnictwo naukowe PWN, Warsaw 1999. ISBN 83-01-12760-0

- Christiansen, Erik (1997). The Northern Crusades. London: Penguin Books. p. 287. ISBN 0-14-026653-4.

- Rez. MA: M. Borgolte (Hg.): Polen und Deutschland vor 1000 Jahren - H-Soz-u-Kult / Rezensionen / Bücher