Wide Awakes

The Wide Awakes were a youth organization and, later, a paramilitary organization cultivated by the Republican Party during the 1860 presidential election in the United States. Using popular social events, an ethos of competitive fraternity, and even promotional comic books, the organization introduced many to political participation and proclaimed themselves the newfound voice of younger voters. The structured, militant Wide Awakes appealed to a generation profoundly shaken by the partisan instability of the 1850s and offered young northerners a much-needed political identity.[1]

_(14594018200).jpg.webp)

Overview

In early March, 1860, Abraham Lincoln spoke in Hartford, Connecticut opposing the spread of slavery and advocating for the right of workers to strike. Five store clerks, who had started a Republican group called the Wide Awakes, decided to join a parade for Lincoln, who delighted in the torchlight escort back to his hotel provided for him after his speech.[2] Over the ensuing weeks, the Lincoln campaign made plans to develop Wide Awakes throughout the country and to use them to spearhead large voter registration drives, knowing that new voters and young voters tend to embrace new and young parties.[3]

Members of the Wide Awakes were described by The New York Times as"...young men of character and energy, earnest in their Republican convictions and enthusiastic in prosecuting the canvass on which we have entered."[4] In Chicago on October 3, 1860, 10,000 Wide Awakes marched in a three-mile procession. The story of this rally occupied eight columns of the Chicago Tribune. In Indiana, as one historian reports:

1860 was the most colorful in the memory of the Hoosier electorate. “Speeches, day and night, torch-light processions, and all kinds of noise and confusion are the go, with all parties,” commented the “independent” Indianapolis Locomotive. Congressman Julian too was impressed by the “contrivance and spectacular display” which prevailed in the current canvass. Each party took unusual pains to mobilize its followers in disciplined political clubs, but the most remarkable of these were the Lincoln “Rail Maulers” and “Wide Awakes,” whose organizations extended throughout the state. Clad in gaudy uniforms the members of these quasi-military bands participated in all Republican demonstrations. The “Wide Awakes” in particular were well drilled and served as political police in escorting party speakers and in preserving order at public meetings. Party emulation made every political rally the occasion for carefully arranged parades through banner-bedecked streets, torchlight processions, elaborate floats and transparencies, blaring bands, and fireworks.[5]

By the midpoint of the 1860 campaign, Republicans bragged that they had Wide Awake chapters in every county of every Northern (free) state.[3] By the day of Lincoln's election as president there were 500,000 members. The group remained active for several decades.[2]

Rituals

Uniform and tactics

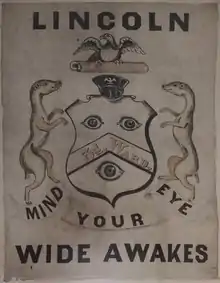

The standard Wide Awake uniform consisted of a full robe or cape, a black glazed hat, and a torch six feet in length to which a large, flaming, pivoting whale-oil container was mounted. Its activities were conducted primarily in the evening and consisted of several night-time torch-lit marches through cities in the northeast and border states. The Wide Awakes adopted the image of a large eyeball as their standard banner.

Chapter organization

Little is known about the national organization of the Wide Awakes, if indeed any formal governing body existed at all. The clubs seem to have been organized by city into local chapters. Surviving minutes of the Waupun, Wisconsin Wide Awakes chapter restrict membership to males age 18 and older. The member had to "furnish himself with the style of uniform adopted by this Club." The chapter had a military-style officer system consisting of a Captain and 1st through 4th Lieutenants.

The Captain shall have command of the Club at all times; in his absence the Lieutenants shall have command in the order of their rank. Every member of this club shall attend all the meetings whether regular or special; and when on duty or in attendance at the meetings, shall obey the officers in command, and shall at all times perform such duties as shall be required of him by the officers in command.[6]

Social dimensions

Whatever their names marching clubs of both parties often had bands and fancy uniforms. The social dimensions have been described:[7]

The young men and boys who joined the Wide-Awakes, Invincibles, and other marching clubs were sold inexpensive uniforms and taught impressive march maneuvers. In Marion the Wide-Awake uniform consisted of an oil cloth cape and cap and a red sash, which along with a lamp or torch cost $1.33. Their “worm fence march” can be imagined, as can a nice connection to Lincoln as rail splitter—a connection that does remind us of the log-cabin and hard cider symbolism of earlier days [of 1840]. The more important connection to be made, however, is to the “militia fever” of the 1850s. Many Americans north and south delighted in military uniforms and titles, musters and parades, and the formal balls their companies sponsored during the winter social season. Their younger brothers no doubt delighted in aping them, so far as $1.33 would allow, while their parents were provided with a means by which youthful rowdyism was, for a time, channeled into a military form of discipline. The regular campaign clubs, meanwhile, were given a different attraction. One of the first items of business, once the club was organized, was to invite “the ladies” to meetings. Many members were single young men, and the campaign occurred during a relatively slow social season following the picnics, steamboat excursions, and other outings of the summer, and preceding the balls sponsored by militia companies, fire companies, and fraternal lodges during the winter. Campaign clubs helped to extend and connect the social seasons for single young men and women, and gave both an occasion for high-spirited travel. “Coming home there was fun,” wrote the Democratic editor of a Dubuque Republican club excursion to a rally in Galena. “There were frequent ‘three cheers for Miss Nancy Rogers.’ ... Captain Pat Conger was the best looking man on the ground and we can only say that it is a pity he is not a Democrat.”

Mission statement

Typical Wide Awakes chapters also adopted an unofficial mission statement. The following example comes from the Chicago Chapter:[8]

- To act as a political police.

- To do escort duty to all prominent Republican speakers who visit our place to address our citizens.

- To attend all public meetings in a body and see that order is kept and that the speaker and meeting is not disturbed.

- To attend the polls and see that justice is done to every legal voter.

- To conduct themselves in such a manner as to induce all Republicans to join them.

- To be a body joined together in large numbers to work for the good of the Republican Ticket.

Membership certificate

_is_a_member_of_the_(blank)_Wide-awake_Club_LCCN2004665362.jpg.webp)

The membership certificate of the Wide-Awake Club has a central vignette showing crowds and troops before the U. S. Capitol. Some of the troops march in long parade lines, others fire cannons into the air toward the Capitol. Crowds line the Capitol steps, flanking a lone figure, probably Abraham Lincoln, who ascends toward the building's entrance. The certificate is framed by an American flag draped over a rail fence, with olive branches at the top. In the upper corners are oval medallions of Abraham Lincoln (left) and running mate Hannibal Hamlin (right). Rail-splitter's mallets appear in the corners. A vigilant eye peers from a halo of clouds at the center. On either side stand uniformed members of the society, wearing their characteristic short capes and visored caps. One holds a staff and a lantern (left), and the other holds a burning torch. Below, an eagle on a shield holds a streamer “E Pluribus Unum,” arrows, and olive branch. Broken shackles lie before him. In the left distance, the sun rises over a mountainous landscape and a locomotive chugs across the plains. On the right is a more industrial scene: an Eastern city with its harbor full of boats. In the foreground a man hammers a wedge into a wooden rail.[9]

Stone's Prairie Riot

In August 1860 a political rally was scheduled to be held at Stone's Prairie in Adams County, Illinois, near the modern village of Plainville.[10] This area, in far western Illinois, was familiar to two of the presidential candidates. Although the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln, was known in the area, his Democratic opponent, Stephen Douglas, had practiced law nearby. In addition to local animosity, Adams County was close to the border with Missouri, a slave state.

The rally was organized by the Republicans. When it was initially announced, there was an invitation to Democratic speakers. Although the invitation was later withdrawn, this fact was not widely disseminated, resulting in confusion as to whether this was to be a Republican rally, or a debate between Republican and Democratic supporters.

During the 1860 campaign, it was a common practice for settlements to raise poles, as much as 150 feet (50 meters) high. The political parties hung flags, and effigies of the candidates they opposed, from the poles.

On the way to the rally, the Quincy Wide Awakes passed through Payson, the residents of which had erected a pole with an offensive effigy of Lincoln astride a rail. The Wide Awakes, however, carried a banner with an equally offensive depiction of a drunken Douglas falling over a pile of rails. An early confrontation was avoided, with the Wide Awakes proceeding to Stone's Creek.

The August 25, 1860, rally involved around 7000 participants. Democrats appeared, expecting to hear their candidates in a debate. They were instead treated to a podium of Republicans, whom they heckled. The Wide Awakes defended the speakers, and a general melee resulted, involving several hundred men.

After the rally, the Wide Awakes returned through Payson, where they found a hundred Democrats guarding their pole. Although Wide Awakes avoided confrontation, shots were fired at them while leaving town. The Wide Awakes' flag was pierced by shots, and several were reported to have been injured.

Southern reaction

In 1860, Texas Senator Louis T. Wigfall alleged, falsely, that Wide Awakes were behind a wave of arson and vandalism in his home state of Texas. Historians have found no evidence whatever of any such conspiracy, but they do report that in Texas, in 1860, a statewide hysteria over nonexistent slave revolts led to the lynching of 30–100 slaves and whites in the so-called Texas Troubles.[11]

The Wide Awakes never marched anywhere in the South, in 1860, but they represented the South's greatest fear, an oppressive force bent on marching down to their lands, liberating the slaves and pushing aside their way of life. Their outfits and equipment only further incited this fear with beliefs that “they parade at midnight, carry rails to break open our doors, torches to fire our dwellings, and beneath their long black capes the knife to cut our throats”.[12] To the South, the Wide Awakes were only a taste of what was to come if Lincoln were to be elected. The North would not compromise, and would, if need be, force themselves upon the great South. "One –half million of men uniformed and drilled, and the purpose of their organization to sweep the country in which I live with fire and sword."[13] This mindset was not appeased by the wide acceptance of the Wide Awakes in the North. On October 25, 1858, Senator Seward of New York stated to an excited crowd, "a revolution has begun" and alluded to Wide Awakes as "forces with which to recover back again all the fields ... and to confound and overthrow, by one decisive blow, the betrayers of the constitution and freedom forever." To the South, the Wide Awakes and the North, would only be content when the South was fully dominated.

The South recognized the need for their own Wide Awakes, and thus started a movement to create "a counteracting organization in the South,"[14] dubbed the "Minutemen." The South viewed the Wide Awakes as the North's private army, and thus they determined on creating their own. They would no longer entertain the "abhorrence of the rapine, murder, insurrection, pollution and incendiarism which have been plotted by the deluded and vicious of the North, against the chastity, law and prosperity of innocent and unoffending citizens of the South."[15] The Minutemen were the South's unofficial army. Like that of the Wide Awakes, they were expected "to form an armed body of men ... whose duty is to arm, equip and drill, and be ready for any emergency that may arise in the present perilous position of Southern States."[16] The fear of the Wide Awakes resulted in Minutemen companies forming all over the South. Like their enemy, they too held torch rallies and wore their own uniforms, complete with an official badge of "a blue rosette ... to be worn upon the side of the hat."[16]

Wartime activities

After Lincoln called out all the militia in April 1861, the Republican Wide Awakes, the Democratic "Douglas Invincibles," and other parade groups volunteered en masse for the Union army. In 1864, reports of political rallies note that "The Northwestern Wide Awakes, the Great Western Light Guard Band, and the 24th Illinois Infantry" were at a Chicago meeting. On November 5, the Chicago Union Campaign Committee (the name of Lincoln's party that year) declared:

"On Tuesday next the destiny of the American Republic is to be settled. We appeal to Union men. We appeal to merchants to close their stores, manufacturers to permit their clerks and laborers to go to the polls, the Board of Trade to close, the Union Leagues and Wide Awakes to come out. The rebellion must be put down."[17]

Defense of St. Louis

In early 1861, the Wide Awakes chapter of St. Louis became involved in paramilitary operations at the outbreak of the Civil War.[18] Aided by Francis Preston Blair, Jr. and army Captain Nathaniel Lyon, the St. Louis Wide Awakes smuggled armaments into the city and trained secretly in a warehouse. The purpose was to prepare them for defense of the federal St. Louis Arsenal, which Confederate supporters wanted to seize. Lyon employed his political connections through Blair to obtain an appointment as commanding officer over the arsenal and, having received his promotion, promptly moved the St. Louis Wide Awakes into the arsenal under cover of night.

Lyon's Wide Awakes, newly mustered into the Federal army, were used on May 10, 1861 to arrest a division of the Missouri State Militia near St. Louis in what would become known as the Camp Jackson Affair. As the captured militia men were marched toward the arsenal later that day a riot erupted in which scores of civilians were shot or killed. This event marked the effective beginning of Civil War violence in Missouri.

See also

- History of the United States Republican Party

- American election campaigns in the 19th century

References

- Grinspan, Jon (September 2009). ""Young Men for War": The Wide Awakes and Lincoln's 1860 Presidential Campaign". Journal of American History. 96 (2): 357–378. doi:10.1093/jahist/96.2.357. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- "The Wide Awakes". Hartford Courant Connecticut Historical Society. April 1, 2017.

- Chadwick, Bruce (2009). Lincoln for President: An Unlikely Candidate, An Audacious Strategy, and the Victory No One Saw Coming. Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks. pp. 147–149. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- "The Wide-Awake Parade". The New York Times. October 3, 1860. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- Kenneth Stampp, Indiana Politics During the Civil War (1949) p 45

- The Waupun Times, August 1, 1860

- Glenn C. Altschuler and Stuart M. Blumin; Rude Republic: Americans and Their Politics in the Nineteenth Century Princeton University Press, 2000 p. 63

- Franklin, Pennsylvania Repository and Transcript

- Library of Congress: Free speech, free soil, free men This is to certify that ... is a member ...

- Iris A. Nelson and Walter S. Waggoner, The Stone's Prairie Riot of 1860, Journal of Illinois History, Vol. 5, p. 19 (Spring 2002)

- Texas Troubles Another forty-one suspected Unionists were hanged by vigilantes in Texas in 1862

- Richmond Enquirer – September 28, 1860 (Valley of the Shadow)

- Louis T. Wigfall – December 6, 1860 (Great Debates in American History)

- Marshal Texan Republican – November 17, 1860 (Valley of the Shadow)

- Indiana Courier – October 27, 1860 (Valley of the Shadow)

- The Constitutional Union – November 16, 1860 (Valley of the Shadow)

- Philip Kinsley; The Chicago Tribune: Its First Hundred Years 1943, p. 348, 349

- Struggle for St. Louis; by Anthony Mondachello

Sources

- Paul F. Boller Jr.; Presidential Campaigns 1996

- Philip Kinsley; The Chicago Tribune: Its First Hundred Years 1943.

- Frank L Klement; Dark Lanterns: Secret Political Societies, Conspiracies, and Treason Trials in the Civil War (1984)

External links

- The Wide Awakes by Louis T. Wigfall, December 6, 1860

- The Wide Awakes Lincoln/Net

- Abraham Lincoln, a History Volume 2 John Hay and John Nicolay

- Struggle for St. Louis by Anthony Mondachello

- Circular regarding uniform and the organization of the club Library of Congress

- The Wide Awake quick step. 1860 Library of Congress