Willem Verstegen

Willem Verstegen (c. 1612 – 1659) was a merchant in service of the Dutch East India Company and chief trader of factory in Dejima.

Life

Willem Verstegen was born around 1612 in Vlissingen, Netherlands. In 1629, he completed his apprenticeship, and following a short stay in Batavia, he was sent to Japan in 1632. There he was first employed at the factory (trading post) in Firando (present-day Hirado, Nagasaki). In 1633, he became factor and was assigned to Dejima, where he met several other Hollanders who were survivors of the shipwrecked galleon De Liefde. They had remained there since 1609 and were trading independently. The most prominent among them was Melchior van Santvoort, who had married a Japanese women and with whom he begot a daughter. Not long after arriving in Dejima, Verstegen asked Santvoort's daughter to marry him.[1]

In 1635, he was appointed to the position of trader. On December 7 of that year, Verstegen wrote to Governor Antonie van Diemen that he had learned of some Japan's islands (at around the 37th parallel north) where almost everything was made of gold and silver. This report of the gold and silver islands so captured their imagination that two expeditions were later outfitted in order to find the islands.[1][2]

In 1639, all Japanese wives with European husbands were ordered by the shōgun to leave the country along with their children. So, Willem Verstegen married Santvoort's daughter on Formosa on their way to Batavia.[1] After their arrival, an expedition under command of Matthijs Quast was outfitted to search the gold and silver islands, but was unsuccessful and abandoned the search. A second expedition led by Maarten Gerritsz Vries and Hendrick Cornelisz Schaep departed in 1643.[3][4] Schaep and nine of his crew were taken prisoner in Yamada when they tried to supply their ship with fresh water.[5]

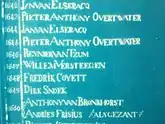

Willem Verstegen replaced Renier van Tzum as chief trader (VOC Opperhoof) in the factory of Dejima and remained in this function from October 28, 1646, to October 10, 1647. He paid an obligatory visit to Shōgun Tokugawa Iemitsu in Edo, bringing with him two camels, a civet, a cassowary, two cockatoos, medicine, and a perspectiefkast (a miniature diorama in a chest or peepshow box, possibly by Samuel Dirksz van Hoogstraten who was known for this craft). Verstegen's report of his trip to Edo is extremely detailed: he mentioned the names of places, described the landscape, recounted what he saw and heard.[6] The Swede Frederick Coyett became his successor as chief trader in Dejima.

In 1651, Verstegen was appointed to Commissioner in Tonkin, Vietnam, where he discovered a large network of private trading. Afterwards, he was sent to Formosa and resided in Fort Zeelandia to examine the bookkeeping. Zacharias Wagenaer was his clerk, who later also was appointed as chief trader in Deshima.[7]

Verstegen gained an extraordinary position on the Counsel of India (central governing body of the Dutch Asian colonies), but was recalled in 1652 back to the Netherlands. Not much is known of this period until February 1658, when Verstegen was in Dutch Suratte, accompanied by both his sons Geraerdt and Melchior, his daughter, and a niece. On January 11, 1659, he packed a few wagons, hired some people, and travelled to Ahmedabad to enlist himself in the army of Dara Shikoh. Shikoh was embroiled in a succession war and had promised great riches to European cannoneers. As reported on October 6, 1659, Verstegen was killed during a battle near Ajmer.[1]

See also

References

- P.H. Pott, Willem Verstegen, een extra-ordinaris Raad van Indië als avonturier in India in 1659, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 112, 1956, no: 4, Leiden (Portable Document Format (PDF))

- Abel Janszoon Tasman's Journal

- Werkstuk Geschiedenis De Breskens | scholieren.com

- Michel, Wolfgang (1993), Travels of the Dutch East India Company in the Japanese Archipelago. Lutz Walter (ed.): Japan - A Cartographic Vision, pp. 31-39.

- Hesselink, R. H. (2001), Prisoners from Nambu: Reality and Make-Believe in 17th- Century Japanese Diplomacy. University of Hawaii Press.

- Historiographical Institute at the University of Tokyo, Japans Daghregister sedert 28 October 1646 tot 10 October 1647

- Wolfgang Michel, Zacharias Wagner und Japan (I) – Ein Auszug aus dem Journal des Donnermanns (The Autobiography of Zacharias Wagner), July 1987