Cassowary

The Cassowary (/ˈkæsəwɛəri/), genus Casuarius, is a ratite (flightless bird without a keel on its sternum bone) that is native to the tropical forests of New Guinea (Papua New Guinea and Indonesia), East Nusa Tenggara, the Maluku Islands, and northeastern Australia.[3]

| Cassowary | |

|---|---|

| |

| Southern cassowary | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Casuariiformes |

| Family: | Casuariidae Kaup, 1847[1] |

| Genus: | Casuarius Brisson, 1760 |

| Type species | |

| Casuarius casuarius | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

There are three extant species. The most common of these, the southern cassowary, is the third-tallest and second-heaviest living bird, smaller only than the ostrich and emu.

Cassowaries feed mainly on fruit, although all species are truly omnivorous and will take a range of other plant food, including shoots and grass seeds, in addition to fungi, invertebrates, and small vertebrates. Cassowaries are very wary of humans, but if provoked they are capable of inflicting serious, even fatal, injuries to both dogs and people. The cassowary has often been labeled "the world's most dangerous bird".[4]

Taxonomy, systematics, and evolution

The genus Casuarius was erected by the French scientist Mathurin Jacques Brisson in his Ornithologie published in 1760.[5] The type species is the southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius).[6] The Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus had introduced the genus Casuarius in the sixth edition of his Systema Naturae published in 1748,[7] but Linnaeus dropped the genus in the important tenth edition of 1758 and put the southern cassowary together with the common ostrich and the greater rhea in the genus Struthio.[8][9] As the publication date of Linnaeus's sixth edition was before the 1758 starting point of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, Brisson, and not Linnaeus, is considered as the authority for the genus.[10]

Cassowaries (from Malay kasuari)[11] are part of the ratite group, which also includes the emu, rheas, ostriches, and kiwi, as well as the extinct moas and elephant birds. Three extant species are recognised, and one extinct:

| Image | Scientific name | Common Name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casuarius casuarius | Southern cassowary or double-wattled cassowary | southern New Guinea, northeastern Australia, and the Aru Islands, mainly in lowlands[3] |

| Casuarius bennetti | Dwarf cassowary or Bennett's cassowary | New Guinea, New Britain, and Yapen, mainly in highlands[3] |

| Casuarius unappendiculatus | Northern cassowary or single-wattled cassowary | Northern and western New Guinea, and Yapen, mainly in lowlands[3][12] |

| (Extinct) † | Casuarius lydekkeri | Pygmy cassowary or small cassowary | Pleistocene fossils of New South Wales[13] and Papua New Guinea[14] |

Most authorities consider the taxonomic classification above to be monotypic, however, several subspecies of each have been described,[15] and some of them have even been suggested as separate species, e.g., C. (b) papuanus.[12] The taxonomic name C. (b) papuanus also may be in need of revision to Casuarius (bennetti) westermanni.[16] Validation of these subspecies has proven difficult due to individual variations, age-related variations, the scarcity of specimens, the stability of specimens (the bright skin of the head and neck—the basis of describing several subspecies—fades in specimens), and the practice of trading live cassowaries for thousands of years, some of which are likely to have escaped or deliberately introduced to regions away from their origin.[12]

The evolutionary history of cassowaries, as of all ratites, is not well known. A fossil species was reported from Australia, but for reasons of biogeography this assignment is not certain and it might belong to the prehistoric Emuarius, which were cassowary-like primitive emus.

All ratites are believed to have originally come from the super-continent Gondwana, which separated around 180 million years ago. Studies show that ratites continued to evolve after this separation into their modern counterparts.[17]

Description

Typically, all cassowaries are shy birds that are found in the deep forest. They are adept at disappearing long before a human knows they were there. The southern cassowary of the far north Queensland rain forests is not well studied, and the northern and dwarf cassowaries even less so.

Females are larger and more brightly coloured than the males. Adult southern cassowaries are 1.5 to 1.8 m (5–6 ft) tall, although some females may reach 2 m (6.6 ft),[18] and weigh 58.5 kg (130 lb).[12]

All cassowaries have feathers that consist of a shaft and loose barbules. They do not have rectrices (tail feathers) or a preen gland. Cassowaries have small wings with 5–6 large remiges. These are reduced to stiff, keratinous quills, resembling porcupine quills, with no barbs.[12] A claw exists on each second digit of the feet.[19] The furcula and coracoid are degenerate, and their palatal bones and sphenoid bones touch each other.[20] These, along with their wedge-shaped body, are thought to be adaptations to ward off vines, thorns, and saw-edged leaves, allowing them to run quickly through the rainforest.[21]

Cassowaries have three-toed feet with sharp claws. The second toe, the inner one in the medial position, sports a dagger-like claw that may be 125 mm (5 in) long.[22] This claw is particularly fearsome since cassowaries sometimes kick humans and other animals with their powerful legs. Cassowaries can run at up to 50 km/h (30 mph) through the dense forest and can jump up to 1.5 m (5 ft). They are good swimmers, crossing wide rivers and swimming in the sea.[19]

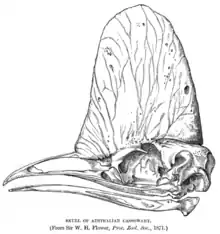

All three species have a keratinous skin-covered casque on their heads that grows with age. The casque's shape and size, up to 18 cm (7 in), is species-dependent. Casuarius casuarius has the largest and Casuarius bennetti the smallest (tricorn shape), with Casuarius unappendiculatus having variations in between. Contrary to earlier findings,[23] the hollow inside of the casque is spanned with fine fibres that are believed to have an acoustic function.[24] Several functions for the casque have been proposed. One is that they are a secondary sexual characteristic. Other suggested functions include being used to batter through underbrush, as a weapon in dominance disputes, or for pushing aside leaf litter during foraging. The latter three are disputed by biologist Andrew Mack, whose personal observation suggests that the casque amplifies deep sounds.[25]

Earlier research indicates the birds lower their heads when running "full tilt through the vegetation, brushing saplings aside and occasionally careening into small trees. The casque would help protect the skull from such collisions". Cassowaries eat fallen fruit and consequently spend much time under trees where seeds the size of golfballs or larger fall from heights of up to 30 m (100 ft); the wedge-shaped casque may protect the head by deflecting falling fruit.

It also has been speculated that the casques play a role in either sound reception or acoustic communication. This is related to a discovery that at least the dwarf cassowary and southern cassowary produce very-low frequency sounds, which may aid in communication in dense rainforest.[25] The "boom" vocalisation that cassowaries produce is the lowest-frequency bird call known and is at the lower limit of human hearing.[26] A cooling function for the very similar casques of guineafowl has been proposed.

The average lifespan of wild cassowaries is believed to be about 40 to 50 years.[27]

Distribution and habitat

Cassowaries are native to the humid rainforests of New Guinea, nearby smaller islands, East Nusa Tenggara, The Maluku Islands and to northeastern Australia.[3] They will, however, venture out into palm scrub, grassland, savanna, and swamp forest.[20] It is unclear whether some island populations are natural or the result of human trade in young birds.

Behaviour and ecology

Cassowaries are solitary birds except during courtship, egg-laying, and sometimes around ample food supplies.[20] The male cassowary defends a territory of about 7 km2 (1,700 acres) for himself and his mate. Female cassowary have larger territories, overlapping those of several males.[27] While females move among satellite territories of different males, they appear to remain within the same territories for most of their lives, mating with the same, or closely related, males over the course of their life spans.

Courtship and pair bonding rituals begin with the vibratory sounds broadcast by females. Males approach and run with necks parallel to the ground while making dramatic movements of the head, which accentuate the frontal neck region. The female approaches drumming slowly. The male will crouch upon the ground and the female will either step on the male's back for a moment before crouching beside him in preparation for copulation, or she may attack. This is often the case with the females pursuing the males in ritualistic chasing behaviours that generally terminate in water. The male cassowary dives into water and submerges himself up to his upper neck and head. The female pursues him into the water where he eventually drives her to the shallows where she crouches making ritualistic motions of her head. The two may remain in copulation for extended periods of time. In some cases another male may approach and run off the first male. He will climb onto her to copulate as well.

Males are far more tolerant of one another than females, which do not tolerate the presence of other females.

Reproduction

The cassowary breeding season starts in May to June. Females lay three to eight large, bright green or pale green-blue eggs in each clutch into a heap of leaf litter prepared by the male.[20] The eggs measure about 9 by 14 cm (3.5 by 5.5 in) – only ostrich and emu eggs are larger.

The male incubates those eggs for 50–52 days, removing or adding litter to regulate the temperature, then protects the chicks, who stay in the nest for about nine months. He defends them fiercely against all potential predators, including humans. The young males later go off to find a territory of their own.[20][27]

The female does not care for the eggs or the chicks, but rather moves on within her territory to lay eggs in the nests of several other males.

Young cassowaries are brown and have buffy stripes. They are often kept as pets in native villages [in New Guinea], where they are permitted to roam like barnyard fowl. Often they are kept until they become nearly grown and someone gets hurt. Mature cassowaries are placed beside native houses in cribs hardly larger than the birds themselves. Garbage and other vegetable food is fed to them, and they live for years in such enclosures; in some areas their plumage is still as valuable as shell money . Caged birds are regularly bereft of their fresh plumes.[21]

Diet

Cassowaries are predominantly frugivorous, but omnivorous opportunistically when small prey is available. Besides fruits, their diet includes flowers, fungi, snails, insects, frogs, birds, fish, rats, mice, and carrion. Fruit from at least 26 plant families has been documented in the diet of cassowaries. Fruits from the laurel, podocarp, palm, wild grape, nightshade, and myrtle families are important items in the diet.[20] The cassowary plum takes its name from the bird.

Where trees are dropping fruit, cassowaries will come in and feed, with each bird defending a tree from others for a few days. They move on when the fruit is depleted. Fruit, even items as large as bananas and apples, is swallowed whole.

Cassowaries are a keystone species of rain forests because they eat fallen fruit whole and distribute seeds across the jungle floor via excrement.[20]

As for eating the cassowary, it is supposed to be quite tough. Australian administrative officers stationed in New Guinea were advised that it "should be cooked with a stone in the pot: when the stone is ready to eat so is the Cassowary".[28]

Role in seed dispersal and germination

Cassowaries feed on the fruit of several hundred rainforest species and usually pass viable seeds in large, dense scats. They are known to disperse seeds over distances greater than a kilometre, and thus play an important role in the ecosystem. Germination rates for seeds of the rare Australian rainforest tree Ryparosa were found to be much higher after passing through a cassowary's gut (92% versus 4%).[29]

Status and conservation

The southern cassowary is endangered in Queensland. Kofron and Chapman (2006) assessed the decline of this species. They found that, of the former cassowary habitat, only 20–25% remains. They stated that habitat loss and fragmentation is the primary cause of decline.[30] They then studied 140 cases of cassowary mortality and found that motor vehicle strikes accounted for 55% of the deaths, and dog attacks produced another 18%. Remaining causes of death included hunting (5 cases), entanglement in wire (1 case), the removal of cassowaries that attacked humans (4 cases), and natural causes (18 cases), including tuberculosis (4 cases). The cause for 14 cases were indicated as, for unknown reasons.[30]

Hand feeding of cassowaries poses a significant threat to their survival because it lures them into suburban areas. There, the birds are more susceptible to encounters with vehicles and dogs.[31] Contact with humans encourages cassowaries to take food from picnic tables. Feral pigs also are a significant threat to their survival. They destroy nests and eggs of cassowaries, but their worst effect is as competitors for food, which may be catastrophic for the cassowaries during lean times.[32][33]

In February 2011 Cyclone Yasi destroyed a large area of cassowary habitat, endangering 200 of the birds – approximately 10% of the total Australian population.[34]

The Mission Beach community in far north Queensland holds an annual Cassowary Festival in September where funds are raised to map the Mission Beach Cassowary Corridor.

In captivity

The cassowary has solitary habits and breeds less frequently in zoos than other ratites such as ostrich and emu. Unlike other ratites, it lives exclusively in tropical rainforest, and it is important to recreate this habitat carefully. Unlike the emu, which will live with other sympatric species, such as kangaroos, in "mixed Australian fauna" displays, the cassowary does not cohabit well among its own kind. Individual specimens must even be kept in separate enclosures, due to their solitary and aggressive nature. Territoriality is one of their most important characteristics.

The double-wattled cassowary (Casuarius casuarius) is the most popular species in captivity and it is fairly common in European and American zoos, where it is known for its unmistakable appearance. As of 2019 only Weltvogelpark Walsrode in Germany has all three species of cassowary in its collection: single-wattled cassowary (Casuarius unappendiculatus) and Bennett's cassowary (Casuarius bennetti), both of which are endemic to the tropical rainforest of New Guinea, and the dwarf cassowary, the smallest species. If subspecies are recognised, Weltvogelpark Walsrode has Casuarius bennettii westermanni and Casuarius unappendiculatus rufotinctus.

Relationship with humans

Some New Guinea Highlands societies capture cassowary chicks and raise them as semi-tame poultry, for use in ceremonial gift exchanges and as food.[35] They are the only indigenous Australasian animal known to have been partly domesticated by people prior to European arrival.[36] The Maring people of Kundagai sacrificed cassowaries (C. bennetti) in certain rituals.[37] The Kalam people considered themselves related to cassowaries and did not classify them as birds but as kin.[38]

Attacks

Cassowaries have a reputation for being dangerous to people and domestic animals. During World War II American and Australian troops stationed in New Guinea were warned to steer clear of them. In his 1958 book, Living Birds of the World, ornithologist Ernest Thomas Gilliard wrote:

The inner or second of the three toes is fitted with a long, straight, murderous nail which can sever an arm or eviscerate an abdomen with ease. There are many records of natives being killed by this bird.[39]

This assessment of the danger posed by cassowaries has been repeated in print by authors including Gregory S. Paul (1988)[40] and Jared Diamond (1997).[41] A 2003 historical study of 221 cassowary attacks showed that 150 had been against humans: 75% of these had been from cassowaries that had been fed by people, 71% of the time the bird had chased or charged the victim, 15% of the time they kicked. Of the attacks, 73% involved the birds expecting or snatching food, 5% involved defending their natural food sources, 15% involved defending themselves from attack, and 7% involved defending their chicks or eggs. Only one human death was reported among those 150 attacks.[42]

The first documented human death caused by a cassowary was on April 6, 1926. In Australia, 16-year-old Phillip McClean and his brother, age 13, came across a cassowary on their property and decided to try and kill it by striking it with clubs. The bird kicked the younger boy, who fell and ran away as his older brother struck the bird. The older McClean then tripped and fell to the ground. While he was on the ground, the cassowary kicked him in the neck, opening a 1.25 cm (0.5 in) wound that may have severed his jugular vein. The boy died of his injuries shortly thereafter.[43]

Cassowary strikes to the abdomen are among the rarest of all, but there is one case of a dog that was kicked in the belly in 1995. The blow left no puncture, but there was severe bruising. The dog later died from an apparent intestinal rupture.[43]

Another human death due to a cassowary was recorded in Florida on April 12, 2019. The bird's owner, a 75-year-old man who had raised the animal, was apparently clawed to death after he fell to the ground.[4][44][45][46][47]

See also

References

Citations

- Melville, R. V.; Smith, J. D. D., eds. (1987). Official Lists and Indexes of Names and Works in Zoology. ICZN. p. 17.

- "Part 7- Vertebrates". Collection of group names. 2007. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- Clements, J. (2007)

- Mosbergen, Dominique (April 14, 2019). "'World's Most Dangerous Bird' Kills 75-Year-Old Owner In Florida". HuffPost. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie, ou, Méthode contenant la division des oiseaux en ordres, sections, genres, especes & leurs variétés (in French and Latin). Volume 1. Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche. Vol. 1, p. 46, Vol. 5: p. 10, Plate 1 fig 2.

- Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 7.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1748). Systema Naturae sistens regna tria naturæ, in classes et ordines, genera et species redacta tabulisque aeneis illustrata (in Latin) (6th ed.). Stockholmiae (Stockholm): Godofr, Kiesewetteri. pp. 16, 27.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturæ per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Volume 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 155.

- Allen, J.A. (1910). "Collation of Brisson's genera of birds with those of Linnaeus". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 28: 317–335. hdl:2246/678.

- "Article 3". International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (4th ed.). London: International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature. 1999. ISBN 978-0-85301-006-7.

- "cassowary". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Davies, S. J. J. F. (2002)

- Miller, Alden H. (June 19, 1962). "The history and significance of the fossil Casuarius lydekkeri" (PDF). Records of the Australian Museum. The Australian Museum. 25 (10): 235–238. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.25.1962.662. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- Rich, P. V.; Plane, Michael; Schroeder, Natalie (1988). "A pygmy cassowary (Casuarius lydekkeri) from late Pleistocene bog deposits at Pureni, Papua New Guinea" (PDF). Journal of Australian Geology & Geophysics. 10: 377–389.

- "The Taxonomy of the Genus Cassowarius". perron.eu. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- Richard M. Perron (2011). "The taxonomic status of Casuarius bennetti papuanus and C. b. westermanni" (PDF). Bull. B.O.C. 131 (1): 54–58. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 22, 2015. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- "Is A Cassowary A Dinosaur?". Jungle Tours & Trekking.

- buzzle.com

- Harmer, S. F. & Shipley, A. E. (1899)

- Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003)

- Gilliard (1958), p. 23.

- Davies, S. J. J. F. (2002) "Ratites and Tinamous" Oxford University Press. New York, USA

- Crome, F.; Moore, L (1988). "The cassowary's casque". Emu. 88 (2): 123–124. doi:10.1071/MU9880123.

- Naish, D.; Perron, R. (2016). "Structure and function of the cassowary's casque and its implications for cassowary history, biology and evolution". Historical Biology. 28 (4): 507–518. doi:10.1080/08912963.2014.985669. S2CID 84497795.

- Mack, A. L. & Jones, J. (2003)

- Owen, J. (2003)

- "Cassowaries: Casuaridae – Behavior And Reproduction". jrank.org.

- Vader, John, New Guinea: The Tide is Stemmed. NY, Ballantine Books: 1971, p. 35.

- Weber, B. L. & Woodrow, I. E.

- Kofron, C. P. & Chapman, A. (2006)

- Borrell 2008.

- "Feral pigs decimating cassowaries in world heritage-listed Daintree, filmmaker says". www.abc.net.au. May 30, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- International), BirdLife International (BirdLife (August 9, 2018). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Casuarius casuarius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "Cyclone puts cassowary in greater peril". The Independent.

- Bulmer, Ralph (March 1967). "Why is the Cassowary Not a Bird? A Problem of Zoological Taxonomy Among the Karam of the New Guinea Highlands". Man. 2 (1): 5–25. doi:10.2307/2798651. JSTOR 2798651.

- Bourke, R. Michael: History of agriculture in Papua New Guinea in Food and Agriculture in Papua New Guinea, ANU Press, 2009

- Healey, Chris (1991). "Why is the Cassowary sacrificed". Man and a Half: Essays in Pacific Anthropology and Ethnobiology in Honour of Ralph Bulmer (PDF). pp. 234–241.

- Bulmer, Ralph (1967). "Why is the Cassowary Not a Bird? A Problem of Zoological Taxonomy Among the Karam of the New Guinea Highlands". Man. 2 (1): 5–25. doi:10.2307/2798651. ISSN 0025-1496. JSTOR 2798651.

- Gilliard, Thomas E. (1958) Living Birds of the World Doubleday

- Paul, G. S. (1988)

- Diamond, J. (1997)

- Kofron, C. P. (1999)

- Kofron, C. P. (2003)

- The Associated Press (April 13, 2019). "Authorities: Large, flightless bird kills its Florida owner". abcnews.go.com. Alachua, Florida, USA: ABCNews. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Cassowary kills man at farm near Alachua". gainesville.com. Alachua, Florida, USA: The Gainesville Sun. April 13, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- Hackney, Deanna; McLaughlin, Eliott C.; CNN (April 15, 2019). "Cassowary, called 'most dangerous bird,' attacks and kills Florida man". AP NEWS. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- Staff, Our Foreign (April 14, 2019). "Cassowary, world's 'most dangerous bird', kills owner in Florida". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

Cited texts

- Borrell, Brendan (October 2008). "Invasion of the Cassowaries". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012.

- Brands, Sheila (August 14, 2008). "Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification – Genus Casuarius". sn2000.taxonomy.nl. The Taxonomicon. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- "The Cassowary Bird". Buzzle.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2009. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- Clark, Philip (November 5, 1990). "Stay in Touch". The Sydney Morning Herald. Cites "authorities" for the death claim.

- Clements, James (2007). The Clements Checklist of the Birds of the World (6 ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4501-9.

- Crome, F.; Moore, L. (1988). "The cassowary's casque" (PDF). Emu. 88 (2): 123–124. doi:10.1071/MU9880123.

- Davies, S. J. J. F. (2002). Ratites and Tinamous. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854996-2.

- Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003). "Birds I: Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. 8 (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 75–77. ISBN 0-7876-5784-0.

- Diamond, J. (March 1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 165. ISBN 0-393-03891-2.

- Gilliard, E. Thomas (1958) [1958]. "Cassowaries". Living Birds of the World. New York, NY: Doubleday & Company. pp. 23–24.

- Gotch, A. F. (1995) [1979]. "Cassowaries". Latin Names Explained. A Guide to the Scientific Classifications of Reptiles, Birds & Mammals. New York, NY: Facts on File. pp. 178–179. ISBN 0-8160-3377-3.

- Harmer, S. F.; Shipley, A. F. (1899). The Cambridge Natural History. Macmillan and Co. pp. 35–36.

- Kofron, Christopher P. (December 1999). "Attacks to humans and domestic animals by the southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius johnsonii) in Queensland, Australia". Journal of Zoology. 249 (4): 375–81. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb01206.x.

- Kofron, Christopher P. (2003). "Case histories of attacks by the southern cassowary in Queensland". Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 49 (1): 335–8.

- Kofron, Christopher P.; Chapman, Angela (2006). "Causes of mortality to the endangered Southern Cassowary Casuarius casuariusjohnsonii in Queensland, Australia". Pacific Conservation Biology. 12 (3): 175–9. doi:10.1071/PC060175. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- Mack, A. L.; Jones, J. (2003). "Low-frequency vocalizations by cassowaries (Casuarius spp.)". The Auk. 120 (4): 1062–68. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2003)120[1062:lvbccs]2.0.co;2.

- Naish, Darren; Perron, Richard M. (2014). "Structure and function of the cassowary's casque and its implications for cassowary history, biology and evolution". Historical Biology. 28 (4): 507–518. doi:10.1080/08912963.2014.985669. S2CID 84497795.

- Owen, J. (2003). "Does Rain Forest Bird "Boom" Like a Dinosaur?". National Geographic News.

- Paul, Gregory S. (1988). Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 364, 464.

- Perron, Richard M. (2016). Taxonomy of the Genus Casuarius. Quantum Conservation. ISBN 978-3-86523-272-4.

- Perron, Richard M. (2011). "The taxonomic status of Casuarius bennetti papuanus and C. b. westermanni". Bull. B.O.C. 131 (1): 54–58.

- Sclater, P. L. (October 14, 1875). "Cassowaries". Nature. 12 (311): 516–7. Bibcode:1875Natur..12..516S. doi:10.1038/012516a0.

- Underhill, D. (1993). Australia's Dangerous Creatures Reader's Digest. Sydney. ISBN 0-86438-018-6.

- Weber, B. L.; Woodrow, I. E. (2004). "Cassowary frugivory, seed defleshing and fruit fly infestation influence the transition from seed to seedling in the rare Australian rainforest tree, Ryparosa sp. nov. 1 (Achariaceae)". Functional Plant Biology. 31 (5): 505–16. doi:10.1071/FP03214. PMID 32688922.

Uncited text

- Rothschild, Walter (1899). A Monograph of the Genus Casuarius. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, vol. 15, pt. 5, December 1900.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Casuarius. |

| Look up cassowary in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Images and movies of the southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius)—ARKive

- C4 Community for Coastal and Cassowary Conservation—Based in Mission Beach

- Video: Cassowary with 3 chicks drinking water at Elantra Resort, Mission Beach

- Cassowary videos, photos and sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- Ernest Ingersoll (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.