William Bainbridge

William Bainbridge (May 7, 1774 – July 27, 1833) was a Commodore in the United States Navy. During his long career in the young American Navy he served under six presidents beginning with John Adams and is notable for his many victories at sea. He commanded several famous naval ships, including USS Constitution, and saw service in the Barbary Wars and the War of 1812. Bainbridge was also in command of USS Philadelphia when she grounded off the shores of Tripoli in North Africa, resulting in his capture and imprisonment for many months. In the latter part of his career he became the U.S. Naval Commissioner.

William Bainbridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 7, 1774 Princeton, Province of New Jersey, British America |

| Died | July 27, 1833 (aged 59) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Buried | Christ Church Burial Ground Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1798–1833 |

| Rank | Commodore |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Congressional Gold Medal |

| Signature | |

Early life

.jpg.webp)

William Bainbridge was born in Princeton, New Jersey, eldest son of Dr. Absalom Bainbridge and Mary Taylor.[1] His father, a loyalist during the American Revolution, served as a surgeon in the British Army and was convicted of high treason by the State of New Jersey and successfully filed for damages with the American Loyalist Claims Commission. William had two brothers: Joseph, who also became a Navy captain, and John T.; and a sister, Mary. He was raised by his maternal grandfather, John Taylor, Esq., of Middleton, New Jersey as his father left for England in 1783 and his mother remained behind due to her ill health (though his father returned to the United States and died in New York City in 1807).[2][3]

Pre-naval service

In his teens William Bainbridge was already of athletic build and had an energetic and adventurous spirit. He was trained as a seaman in ships in the Delaware River, then considered the best 'school' for seamanship because of the great skill required to navigate that river.[4]

Bainbridge served aboard the small merchant ship Cantor in 1792.[5]

In 1796 after returning from Brazil, Bainbridge served aboard the merchant ship Hope, a small vessel of 140 tons with four nine-pound guns. While he was in port in the Garonne River at Bordeaux preparing for his fourth voyage, the captain of a nearby ship which was under mutiny hailed Bainbridge and asked for help; though outnumbered by seven seamen and being severely wounded by exploding gunpowder, Bainbridge succeeded in helping restore order. For his courage and in recognition of his navigational and seaman skills he was made commander of that ship in 1796 at the age of nineteen.[6]

After leaving France that same year he sailed to the Caribbean. While in port at St. Johns, Bainbridge was hailed by an English schooner, but refused to stop. The English vessel fired guns in response where Bainbridge and his crack crew quickly turned about and with only two guns to a broadside, inflicted enough damage that forced the enemy ship to strike colors and surrender.[6][7][8]

Service in US Navy

Bainbridge saw service in several wars and commanded a number of famous early U.S. Navy vessels including USS George Washington, USS Philadelphia and USS Constitution, ultimately becoming a member of the board of naval commissioners during the latter part of his long naval career.

Quasi-War

With the organization of the United States Navy in 1798, Bainbridge was included in the naval officer corps and in September 1798 was appointed commanding Lieutenant of the schooner USS Retaliation. He was ordered to patrol the waters in the West Indies along with Captain Williams of USS Norfolk, both of whom were under the command of Murray, who was in command of the frigate USS Montezuma.[9] On November 20, 1798, Lt. Bainbridge surrendered Retaliation without resistance to two French frigates, Volontier, with 44 guns and l'Insurgente bearing 40 guns, after he mistook them for British warships and approached them without identifying them.[10] Bainbridge and his crew were taken aboard Volontier where the two French frigates continued in their pursuit of other nearby American vessels. During the flight to capture the Americans, Bainbridge offered words of caution to the French commander of L' Insurgente, Captain St. Laurent, about American strength; this made St. Laurent wait for his consorts far behind him.[11]

Retaliation was the first ship in the nascent United States Navy to be surrendered. Bainbridge was not disciplined for this action.

In March 1799, Bainbridge was appointed Master Commandant of the brig USS Norfolk of 18 guns and ordered to cruise against the French.[12][13]

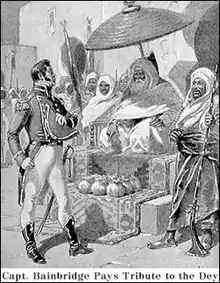

First Barbary War

In 1800 during the months before the First Barbary War broke out, Bainbridge was given the ignominious task of carrying the tribute which the United States still paid to the Dey of Algiers to secure exemption from capture for U.S. merchant ships in the Mediterranean.[14] Upon arrival in the 24-gun USS George Washington, he allowed the harbor pilot to guide him directly under the guns of the fort overlooking the harbor. Upon his arrival the Dey demanded that Bainbridge use his ship to ferry the Algerian ambassador and tributary gifts to Constantinople, and that he fly the Algerian flag during the journey. With George Washington under the guns of the fort and surrounded by the Dey's warships and military personnel Bainbridge reluctantly complied for fear of imprisonment, raised the Algerian flag on his masthead and delivered gifts of animals and slaves to Constantinople.[15][16]

President Jefferson found that bribing the pirate Barbary states did not work, and decided to use force. On May 21, 1803, Bainbridge was placed in command of USS Philadelphia, tasked with enforcing a blockade of Tripoli. Bainbridge mistakenly ran the ship aground on an uncharted reef on October 21, 1803. Bainbridge made the situation worse by putting on all sail before sounding around the boat to determine the actual situation, resulting in driving the ship hard onto the bank. All efforts to refloat her under five hours of cannon fire from Tripolitan gunboats, inaccurate fire that with no shots coming near the powerful frigate, and Bainbridge decided to surrender. Before doing so he ordered all small arms thrown overboard, the powder magazine flooded and the naval signal book destroyed.[17] Soon afterward, the ship floated free after high tide and was captured by the Pasha of Tripoli. Bainbridge and his crewmen were imprisoned in Tripoli for nineteen months.[18]

Lieutenant Stephen Decatur commanding USS Intrepid executed a night raid into Tripoli harbor on February 16, 1804, to destroy Philadelphia. Admiral Horatio Nelson is said to have called this "the most bold and daring act of the Age".[19][20][21]

The capture of Philadelphia and its crew also motivated President Jefferson's decision to send William Eaton, a former Army officer, known for his brash and defiant diplomacy, to Tripoli in 1805 to free the 300 American hostages in what was the first U.S. covert mission to overthrow a foreign government. William Eaton established a group of about 20 Christian (eight of whom were U.S. Marines) and perhaps 100 Muslim mercenaries to begin the takeover of Tripoli starting with Derna. He managed to trek with the small detachment of Marines led by Presley O'Bannon and his mercenary force over 500 miles. Supported at sea by Isaac Hull, Captain of USS Argus, in an effective "combined operation", Eaton led the attack in the Battle of Derna on 27 April 1805. The town's capture, memorialized in the "Marines' Hymn" famous line "to the shores of Tripoli" and the threat of further advance on Tripoli, were strong influences toward peace, negotiated in June 1805 by Tobias Lear and Commodore John Rodgers with the Pasha of Tripoli.

After four separate bombardments from Preble's squadron, Bainbridge was released from the prison in Tripoli on June 3, 1805[22] and returned to the United States and received a warm welcome. Shortly thereafter a Naval Court of Inquiry tasked with looking into his surrender found no evidence of misconduct, and he was allowed to continue serving. On his release, he returned for a time to the merchant service in order to make good the loss of profit caused by his captivity.[14] With the conclusion of the campaign against the Barbary states, the US Navy was downsized and nearly all of her frigates remained in port. Realizing war with the United Kingdom was imminent Bainbridge and Commodore Stewart hastened to Washington to urge President Jefferson and Congress to strengthen the country's naval forces. They concurred with this timely advice and Congress forced a change to this policy that had led the current naval force to decay in early 1809. Satisfied with the results Bainbridge returned to Boston and took command of the navy yard at Charleston.[23]

Bainbridge took command of the frigate USS President in 1809 and began patrolling off the Atlantic coast in September of that year. Bainbridge was transferred to shore duty in June, 1810.[24]

War of 1812

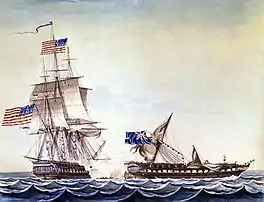

On 15 September, shortly after the War of 1812 broke out between the United Kingdom and the United States, Bainbridge was appointed to command the 44-gun frigate USS Constitution, succeeding Captain Isaac Hull.[25] Constitution was an enormous frigate armed with 24-pounders of 1,533 tons, which had already captured the 18-pounder frigate HMS Guerriere of 1072 tons. Under Bainbridge, she was sent to cruise in the South Atlantic.[14][26]

On 29 December 1812, Bainbridge fell in with the 38-gun HMS Java, off the coast of Brazil. Java was a vessel armed with 18-pounders and of 1,083 tons, formerly the French frigate Renommée.[27][28] She had a crew of 300 men under Captain Henry Lambert[29] and was on her way to the East Indies, carrying the newly appointed Lieutenant-General Hislop of Bombay and his staff along with dispatches to St. Helena, Cape of Good Hope and every British port in the Indian and China Seas.[30] She had an inexperienced crew with only a very few trained seamen, and her men had only had one day's gunnery drill.[14] In addition to her crew, Java was carrying officers and seamen who were to join the British fleet in the East Indies bringing her complement to around 400, among them Captain John Marshall who was to take command of a sloop of war stationed there.[31] Under Bainbridge, Constitution had a well-drilled crew. Java was cut to pieces, with its rigging almost completely destroyed, and was forced to surrender, while having inflicted moderate damage to Constitution, including removing Constitution's helm with shot and hitting the lower masts (which did not fall because of their large diameter). During the action, Bainbridge was wounded twice, but maintained command throughout. Java fought extremely well as compared to the Guerriere and Macedonian which had been taken earlier that year by similarly overwhelming force. Java successfully outmaneuvered the large Constitution until her jib was shot away. If Constitution had been built with smaller diameter masts, she would have been dismasted. Fortunately, Constitution's masts were so wide that the smaller 18 lb shot from Java could not penetrate them. After three hours of intense fighting, Constitution prevailed. Bainbridge replaced the missing helm on Constitution with the one from Java before she was destroyed and sank. To this day, the still-commissioned Constitution (moored in Boston Harbor) sports the helm that Bainbridge salvaged from Java. Java's crew was taken prisoner and put aboard Constitution in the hold. Because of the heavy damage inflicted on Java and the great distance from the American coast, Bainbridge decided to burn and sink the British frigate.[31] On March 3, 1813, President Madison presented Bainbridge with the Congressional Gold Medal for his service aboard Constitution.[32]

Second Barbary War

After the conclusion of the war with Britain, the United States engaged in the Second Barbary War of 1815 (also known as the Algerian War). It was the second of two wars fought between the United States and the Ottoman Empire's North African regencies of Tripoli, Tunis, and Algeria known collectively as the Barbary states. On March 3, 1815, the US Congress authorized deployment of naval power against the Regency of Algiers, and two squadrons were assembled and readied for war. Bainbridge served against the Barbary pirates and was commander of the US squadron sent to Algiers to enforce a blockade, show the extent of American naval resources and determination and enforce the neutrality and peace that was established by Stephen Decatur and William Shaler. The war ended in 1815 with the victory of the United States.[33]

USS Columbus

Bainbridge transported Canova's George Washington from Italy to Boston aboard his flagship USS Columbus. The statue was delivered to Boston, transported to Raleigh, North Carolina, and then installed in the rotunda of the North Carolina State House on December 24, 1821.[34]

Later life

In 1820, Bainbridge served as second for Stephen Decatur in a duel with James Barron that cost Decatur his life. Decatur's wife, along with many historians, believe that Bainbridge had actually harbored a long-standing resentment of the younger more famous Decatur and arranged the duel in a way that made the wounding or killing of one or more duelists very likely.

Between 1824 and 1827, he served on the Board of Navy Commissioners.[35] He died in Philadelphia and was buried there at the Christ Church Burial Ground.

Legacy

Bainbridge was survived by his son William Jr. and four daughters (Mary Taylor Bainbridge Jaudon, Susan Parker Hayes, Louisa Alexina Bainbridge and Lucy Ann Bainbridge). He left some money that was invested in Pennsylvania State bonds, which were sold and invested in other projects. After the American Civil War, Mary T. Jaudon's bonds were mismanaged by her husband's brother, Samuel Jaudon and ultimately became the subject of a United States Supreme Court case, Jaudon v. Duncan.[36]

Several ships of the Navy have since been named USS Bainbridge in his honor, including the U.S. Navy's first destroyer (USS Bainbridge (DD-1)), a unique nuclear-powered destroyer/cruiser (USS Bainbridge (CGN-25)), and a contemporary Arleigh Burke-class destroyer USS Bainbridge (DDG-96). This last ship is known as the ship that rescued the MV Maersk Alabama in the 2009 attempted hijacking by Somali pirates. The now-deactivated Bainbridge Naval Training Center in Port Deposit, Cecil County, Maryland, was named for him.

Other places named after him include Bainbridge Island, Washington, as well as Bainbridge Township, Ohio; Bainbridge, Georgia, county seat of Decatur County; Bainbridge, Indiana;[37] Bainbridge, New York; Bainbridge Street in Philadelphia; Bainbridge Street in Richmond, Virginia, and Old Bainbridge Road in Tallahassee, Florida. Bainbridge Avenue in the Bronx, New York, is also named for William Bainbridge, it runs near Decatur Avenue, named for Stephen Decatur, Jr. in the Norwood section of the Bronx. Bainbridge Street in Montgomery, Alabama, on which street the state capitol building is located, is also named for Bainbridge. Parallel to that Bainbridge Street and beginning directly to its west are streets named for other Barbary War/War of 1812 naval heroes: Decatur Street, named for Stephen Decatur; Hull Street, named for Isaac Hull; McDonough Street, named for Thomas Macdonough; Lawrence Street, named for James Lawrence and Perry Street, named for Oliver Hazard Perry. Bainbridge was also the namesake for Fort Bainbridge, built during the Creek War near Tuskegee, Alabama.

See also

References

- Harris, 1837 p. 18

- Deats, 1904, The Jerseyman, Vol x, P.20

- Jones, 1972, The Loyalists of New Jersey, pp. 15–16

- Cooper, 1846 pp. 10–11

- Barnes, 1897 pp. 9–10

- Barnes, 1896 pp. 73–74

- Barnes, 1897 pp. 19–21

- Harris, 1837 pp. 19–20

- Harris, 1837 p.25

- Barnes, 1897 pp. 45–46

- Cooper, 1846 pp. 15–17

- Barnes, 1897 p.54

- Harris, 1837 pp.36-37

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hannay, David (1911). "Bainbridge, William". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 223.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hannay, David (1911). "Bainbridge, William". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 223. - Boot, Max (2003). The Savage Wars of Peace. New York: Basic Books. p. 12. ISBN 046500721X. LCCN 2004695066.

- Tucker, 2004 pp. 25–26

- Allen, 1905, p.148

- Barnes, 1896 p.79

- Cooper, James Fenimore (May 1853). "Old Ironsides". Putnam's Monthly. I (V). Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- Abbot 1896, Volume I, Part I, Chapter XVI

- See, Leiner, Frederick C., "Searching for Nelson’s Quote", USNI News, United States Naval Institute, February 5, 2013, setting forth the evidence for and against that quote.

- Barnes, 1896 p. 5–304

- Barnes, 1896 p.80

- Harris, 1837 pp. 130–131

- Cooper, 1846 p.59

- Roosevelt, 1883 pp. 117–118

- Barnes, 1896 p. ix

- Hickey, 1989 p. 96

- Barnes, 1896 p.84

- Harris, 1837 pp. 153–154

- Harris, 1837 p.147

- Harris, 1837 pp. 170–171

- Harris, 1837 pp. 198–200

- Haywood, Marshall DeLancey (1902). Bassett, John Spencer (ed.). "Canova's Statue of Washington". The South Atlantic Quarterly. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University. 1: 280–1.

- Cooper, 1846 p.69

- https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/82/165/

- Werner, Nick (April 3, 2012). Best Hikes Near Indianapolis. FalconGuides. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-7627-7355-8.

Bibliography

- Allen, Gardner Weld (1905). Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs.

Houghton Mifflin & Co., Boston, New York and Chicago. p. 354. OCLC 2618279. URL - Barnes, James (1896). Naval actions of the War of 1812.

Harper & Brothers, New York. p. 263. URL - —— (1897). Commodore Bainbridge:from the gunroom to the quarter-deck.

D. Appleton and company. p. 168. ISBN 0945726589. URL1 URL2 - Cooper, James Fenimore (1846). Lives of distinguished American naval officers.

Carey and Hart, Philadelphia. p. 436. OCLC 620356. URL - —— (1853). Old Ironsides. G.P. Putnam, 1853. p. 49. URL

- Dearborn, H. A. S. (2011). The Life of William Bainbridge, Esq of the United States Navy.

Kessinger Publishing. p. 252. URL - Dept U.S.Navy. "Ships Histories Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships".

Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY -- NAVAL HISTORICAL CENTER. Retrieved November 1, 2011. - Harris, Thomas (1837). The life and services of Commodore William Bainbridge, United States navy.

Carey Lea & Blanchard, Philadelphia. p. 254. ISBN 0945726589. E'book1 E'book2 - Hickey, Donald R. (1989). The War of 1812, A Forgotten Conflict.

University of Illinois Press, Chicago and Urbana. ISBN 0-252-01613-0. url-1, url-2 - Roosevelt, Theodore (1883). The naval war of 1812: ...

G.P. Putnam's sons, New York. p. 541. E'book - —— (1901). The naval operations of the war between Great Britain and the United States, 1812–1815.

Little, Brown, and Company, Boston. p. 290. URL1 URL2 URL3 - Tucker, Spencer (2004). Stephen Decatur: a life most bold and daring.

Naval Institute Press, 2004 Annapolis, MD. p. 245. ISBN 1-55750-999-9. URL

Further reading

- Dearborn, H. A. S. The Life of William Bainbridge, Esq. Princeton, N.J.; Princeton University Press, 1931.

- London, Joshua E. Victory in Tripoli: How America's War with the Barbary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005. ISBN 0-471-44415-4.

- Long, David F. Ready to Hazard: A Biography of Commodore William Bainbridge, 1774–1833. Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 1981.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Bainbridge. |