Wind of Change (speech)

The "Wind of Change" speech was an address made by British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan to the Parliament of South Africa, on 3 February 1960 in Cape Town. He had spent a month in Africa visiting a number of what were then British colonies.[1] The speech signalled clearly that the Conservative-led British government had no intention to block the independence to many of these territories.[2][3] The Labour government of 1945–51 had started a process of decolonisation, but this policy had been halted or at least slowed down by the Conservative governments from 1951 onwards.

.jpg.webp)

The speech acquired its name from a quotation embedded in it. Macmillan said:

The wind of change is blowing through this continent. Whether we like it or not, this growth of national consciousness is a political fact.[4]

The occasion was in fact the second time on which Macmillan had given this speech: he was repeating an address already made in Accra, Ghana (formerly the British colony of the Gold Coast) on 10 January 1960. This time it received press attention, at least partly because of the stony reception that greeted it.

Macmillan's Cape Town speech also made it clear that Macmillan included South Africa in his comments and indicated a shift in British policy in regard to South Afrian apartheid with Macmillan saying:

As a fellow member of the Commonwealth it is our earnest desire to give South Africa our support and encouragement, but I hope you won't mind my saying frankly that there are some aspects of your policies which make it impossible for us to do this without being false to our own deep convictions about the political destinies of free men to which in our own territories we are trying to give effect.[4][5]

Background

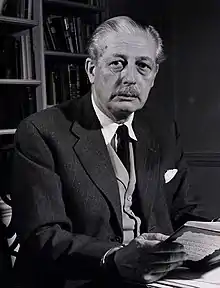

Harold Macmillan, a member of the British Conservative Party, served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. He presided over a time of national prosperity and the easing of Cold War tensions. Despite this, the British Empire, which had spanned a quarter of the world in 1921, was beginning to become financially unsustainable to the British government. Spurred by increasing nationalism in Africa and Asia, the British government made the decision to initiate the process of decolonisation- granting the various colonies of the Empire independence from colonial rule.[6]

The British Empire had begun its dissolution after the end of the Second World War. Many in Britain had come to the conclusion that running the Empire had become more trouble than it was worth. There were many international fears contributing to this conclusion. For example, the fear of Soviet penetration into Africa and the Cold War politics was an international concern that helped initiate the dismantling of the British Empire.[7] The independence of British Somaliland in 1960, along with the "Wind of Change" speech that Macmillan delivered in South Africa earlier in the same year, is what started the decade when the dismantling of the British Empire reached its climax, as no fewer than twenty-seven former colonies in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean left the Empire and became independent nations.[8] At the same time, African nationalists were becoming increasingly demanding in their initiative for self-rule. The path to independence in the Southern African states proved more problematic because the white population in those colonies became hostile towards the idea of black-majority rule.[9]

Gold Coast

The British West African colony of the Gold Coast was, upon independence, renamed Ghana after the ancient African Empire in the area. This had become a place of great promise for the African independence movement in the 1950s. The average level of education were highest in all of Sub-Saharan Africa there and the individuals were putting their weight behind the independence movement. The Gold Coast nationalists had campaigned for home rule even before the Second World War, and before the majority of the colonies of the British Empire had initiated the process of decolonization.[9] Under the leadership of Kwame Nkrumah, the colony became the first to become independent in 1957.[10]

Cold War politics and the fear of communism

The United States was also putting pressure on the United Kingdom at this time. The American government both wanted Britain to decolonize so that they could gain access to new markets and resources, and believed that decolonization was a necessity to prevent communism becoming an attractive option to African nationalist movements of the day.[6]

African nationalism

African nationalism escalated during the Second World War. The British needed secure control over their African colonies for resources to fight the Axis powers. For their help throughout the war, the African colonies wanted to receive rewards in the form of political and economical opportunity. They became bitter when these rewards were not presented to them and started to campaign for independence. Many colonies stood on the edge of a revolution. In the West African colony of Gold Coast, political leader Kwame Nkrumah's Convention People's Party (CPP) orchestrated a campaign of civil disobedience in support of self-government. In the 1951 election, the CPP won thirty-four of thirty-eight seats and Nkrumah became prime minister, resulting in the colony's independence under Nkrumah's leadership as the state of Ghana in 1957.

At the same time, in other colonies of Africa the desire for independence was countered by opposition from white settlers, who generally dominated the colonies politically and economically. They asserted this dominance by denying universal suffrage to Africans and through efforts to persuade the British government to consolidate colonial territories into federations. However, this minority of white settlers could not contain the sense of African nationalism. There were warnings that without a quick transfer of power that African nationalism would undermine colonial rule anyway. In order to obtain cooperation from the new African governments, the British government would need to decolonise and grant them independence (or at least self-rule, which was thought to be a good substitute for direct control of the area).

By 1960, Macmillan's Conservative government was becoming worried about the effects of violent confrontations with the African nationalists in the Belgian Congo and French Algeria. The Conservatives were fearful of this violent activity spilling over into British colonies. This is when Macmillan went to Africa to circulate and deliver his speech "Wind of Change", which is named for its line: "The wind of change is blowing through this continent and whether we like it or not, this growth of national consciousness is a political fact. We must all accept it as a fact, and our national policies must take account of it." Following this speech with surprising speed, Iain Macleod, Colonial Secretary in 1959-1961, decreased the original timetable for independence in East Africa by an entire decade. Independence was granted to Tanganyika in 1961, Uganda in 1962 and Kenya in 1963.[6]

Consequences

Besides restating the policy of decolonisation, the speech marked political shifts that were to occur within the next year or so, in the Union of South Africa and the United Kingdom. The formation of the Republic of South Africa in 1961 and the country's departure from the Commonwealth of Nations were the result of a number of factors, but the change in the British government's attitude to decolonization is usually considered to have been significant.

In South Africa, the speech was received with discomfort.[1][11] There was an extended backlash against the speech from the right of the Conservative Party, who wished that Britain retain its colonial possessions. The speech led directly to the formation of the Conservative Monday Club pressure group.

The speech is also popularly (if inaccurately) known as the "Winds of Change" speech. Macmillan himself, in titling the first volume of his memoirs, Winds of Change (1966), seems to have acquiesced in this popular misquotation of the original text.[12]

The Portuguese Colonial War started in 1961 in Angola, and extended to other Portuguese overseas territories at the time, namely Portuguese Guinea in 1963 and Mozambique in 1964. By refusing to grant independence to its overseas territories in Africa, the Portuguese ruling regime of Estado Novo was criticised by most of the international community, and its leaders Salazar and Caetano were accused of being blind to the so-called "winds of change". After the Carnation Revolution in 1974 and the fall of the Portuguese authoritarian regime, almost all the Portuguese-ruled territories outside Europe became independent countries. Several historians have described the stubbornness of the regime as a lack of sensibility to the "winds of change". For the regime, those overseas possessions were a matter of national interest.

The original delivery and its impact in South Africa

.jpg.webp)

The year 1960 was rife with change. Starting with the surprising announcement by Prime Minister Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd that a referendum would be held in regards to whether South Africa should become a republic; After Harold Macmillan’s speech on 3 February, there was an assassination attempt made against Verwoerd on 9 April, and the African National Congress (ANC) and Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC) were declared illegal in a state of emergency, along with other controversies.[13] Harold Macmillan did not solely compose the speech commonly known as the "Winds of Change"; he had input from numerous friends and colleagues who helped derive the perfect wording for the delicate situation. The Prime Minister wanted to separate the British nation, but also inspire the black nationalists there to pursue their freedom and equality subtly. The other hidden motive is that during this period there was much pressure from the US government for all European nations to initiate decolonization. By announcing to the world that Britain was fully committed to the process of decolonization, they opened themselves up to more political opportunity. This was a bold attempt to address multiple parties and interests at once.[13]

Before he delivered the speech, Macmillan went on a six-week tour of Africa that began on 5 January. He began with Ghana, Nigeria, Rhodesia & Nyasaland and then South Africa where the meeting finally happened with Prime Minister Verwoerd. Macmillan tried to explain the necessity of change brought upon them by the two world wars.[7]

When Harold Macmillan delivered his speech, it was done for multiple reasons. Although the main subject matter of the speech is relating to the separation of Britain from its South African colonies, it also made reference to their discontent with the system of apartheid and it held positive political results for the British government. The speech held promise of major policy change on the topic of their decolonisation, and was actually delivered twice in two different locations. First it was done in Ghana, but there was no press coverage and few people even attended the event in Accra. The second, more widely reported telling was on 3 February in Cape Town and was met with very mixed reviews.

If the speech would be judged on its quality of deliverance and content, it would be considered a success. When considering if this speech was successful, one must place it next to its objectives. The speech did lay down a relatively clear understanding of Britain’s intended exit as a colonial power in Africa, so in the larger scheme it achieved its purpose. However, when considering there is indication that Macmillan’s intent was to sway White South Africans to abandon Verwoerd's apartheid dogma, that part of the speech was a failure. It was an important moment to have such a distinguished, powerful figure from the Western world admonishing the practices and encouraging the black nationalists to achieve equality, but it still was not as groundbreaking or immediately effective as was the implied intent.[13]

There was some belief that the policy outlined in the speech was seen as "British abdication in Africa" and "the cynical abandonment of white settlers".[7] Not everyone felt that it was the right move for the nation to make. However, there was a slightly ambiguous reaction from some of the Black nationalists; they had been prevented from meeting Macmillan – assumingly by Verwoerd – over the course of his visit and were skeptical about his speech at first. Small groups of ANC supporters gathered in both Johannesburg and Cape Town and stood in silence while holding placards with urgings directed at Macmillan. They wanted him to talk with Congress leaders, and reached out to him with banners saying: "Mac, Verwoerd is not our leader." It is even said that Mandela thought the speech was "terrific" and he even made a speech in 1996 that specifically recalled this very address when he addressed the British parliament in Westminster Hall. Albert Luthuli noted that in his speech, Macmillan gave African people ‘some inspiration and hope.’[13]

Some people indicated that Macmillan was very nervous for the entire speech. He would turn the pages with obvious struggle. This could be because he was knowingly presenting a speech that he had intentionally withheld from the South African Prime Minister before. Macmillan had declined giving Verwoerd an advance copy, and merely summed up the main content to him. When the speech was complete there was visible shock on Verwoerd’s face. He apparently leapt up from his seat and immediately responded to Macmillan. He was reportedly calm, and collected when he gave his response – something that was widely admired by the public. He had to save face when Macmillan had dropped a ticking time bomb into speech, yet he managed to respond quickly and well in a game of words he was not accustomed to. He famously responded by saying: "There must not only be justice to the Black man in Africa, but also to the White man".[1][3][13] He said that for these Europeans they had no other home, for Africa was their home now too, and that they also were a strong stance against Communism, for their ways were grounded in Christian values. Saul Dubow stated that "The unintended effect of the speech was to help empower Verwoerd by reinforcing his dominance over domestic politics and by assisting him make two hitherto separate strands of his political career seem mutually reinforcing: republican nationalism on the one hand and apartheid ideology on the other."[13]

Today, the draft and final copies of the speech itself are housed in Oxford University's Bodleian Library.[14]

British reactions and attitudes at home

Most of the reaction following the speech can be seen as a direct response from Conservatives within the British government at the time. Although Macmillan's speech can officially be seen as a declaration of a change in policy regarding the British Empire, prior government actions had already moved towards a slow process of decolonisation in Africa. However, this gradual policy of relinquishing Federation-owned colonies was originally intended to only target areas within West Africa.[15] Areas outside of this particular confinement, with European inhabitants, were not seen as threatened at first by the gradual decolonisation initiated by the British government. As such, the aftermath of Macmillan's speech brought not only great surprise but a feeling of betrayal and distrust by members of the Conservative Party at the time. Lord Kilmuir, a member of Macmillan's Cabinet at the time of the speech went on to regard that:

Few utterances in recent history have had more grievous consequences...in Kenya the settlers spoke bitterly of a betrayal, and the ministers of the Federation approached the British government with equal suspicion.[16]

These feelings not only resounded with European settlers in the African colonies, but were shared by members of Macmillans's own party who felt that Macmillan had taken the party line down the wrong direction. This was illustrated through the speed and scale with which decolonisation occurred. Following this speech therefore, the British government felt pressure from within due to economic and political interests surrounding the colonies. Lord Salisbury, another member of the Conservative Party at the time of this speech, felt that European settlers in Kenya, alongside the African populace, would prefer to remain under British rule irregardless.[17]

Prior to the speech, the Federation government had dismissed suggestions that black-majority rule would be the best action in the colonies of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Because the copperbelt ran through Northern Rhodesia, economic interests presented themselves as an opponent to decolonization. This example can help to illustrate some of the feelings of resentment and betrayal felt by fellow members of the Conservative Party following Macmillan's speech.[16] Additionally, the fear that Britain would appear weak or unstable following a rapid decolonisation of her various colonies was of great concern to many Conservatives at the time of the speech. Although Macmillan argued in his oration that Britain's power had not faded, the economic effects if the Empire was seen as weak would prove worrisome.[18]

On the other hand, other British reactions were concerned with whether the speech truly carried an authentic tone. Although in the speech Macmillan addressed British opposition to apartheid, the fact that the address was officially made in South Africa left media outlets in Britain to question whether there would be any sort of immediate change in policy.[18] Alongside the issue of apartheid, the process of decolonisation as indicated by Macmillan brought forth questions as for the legitimacy and responsibilities of colonial powers once their colonies had been granted independence. Many felt that countries such Ghana, which were among the first to be granted independence from British rule, were only decolonised so quickly due to a lack of economic interests pushing against decolonization. These factors not only created a clash of ideals at home between conservative forces and those who wished to initiate the process of decolonization, but worked to complicate relations between Britain and other nations.[18]

The Conservative Monday Club

As a result of the "Wind of Change" speech, Members of Parliament formed the Conservative Monday Club in attempts to debate party policy change and prevent decolonization. In addition, the motivation behind the group also was founded on the notion that Macmillan had not accurately represented the party's original aims and goals. As a result, the members of this organisation rigidly opposed decolonisation in all forms and represented the feelings of betrayal and distrust following foreign policy changes after the "Wind of Change" speech. Many Conservatives saw the speech as another step towards a complete dismantling of the Empire. The Conservative Monday Club was founded as a direct result of Macmillan's address and as such the reaction of the Conservative Party at home can be seen as both resentful and distrustful of Macmillan.[19]

References

- "On this day: 3 february - 1960: Macmillan speaks of 'wind of change' in Africa". London: BBC. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Hurd, Douglas (24 April 2007). "No going back". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Boddy-Evans, Alistair (8 March 2017). ""Wind of Change" speech". Thought Co. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Harold Macmillan:The wind of change" (PDF). Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- The White Tribe of Africa, David Harrison, University of California Press, 1983, page 163

- Watts, Carl Peter (2011). "The 'Wind of Change': British Decolonisation in Africa, 1957–1965". History Review (71): 12–17.

- Ovendale, Ritchie(June 1995). "Macmillan and the Wind of Change in Africa, 1957–1960". The Historical Journal 38(2):455–477. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- "How Britain said farewell to its Empire". BBC News. 23 July 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- "The Story of Africa: Gold Coast to Ghana". BBC World Service. BBC. 25 February 2013.

- Binaisa, Godfrey L. (1977). ""Organization of African Unity and Decolonization: Present and Future Trends."". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 432: 52–69. JSTOR 1042889.

- Dowden, Richard (20 September 1994). "1960: 'wind of change' that created a storm". Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Winds of Change 1914-1939 Harold Macmillan First Edition 1966 - London - Macmillan 9" by 6" - 664pp | Scarce and decorative antiquarian books and first editions on all subjects | Rare Books". Rooke Books. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- Dubow, Saul (December 2011). "Macmillan, Verwoerd, and the 1960 'Wind of Change' Speech" (PDF). The Historical Journal. 54 (4): 1087–1114. doi:10.1017/s0018246x11000409. JSTOR 41349633.

- "Harold Macmillan's 'Wind of Change' speech". Treasures of the Bodleian. Oxford University. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- "BBC On This Day". BBC. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Horowitz, Dan (1970). "Attitudes of British Conservatives towards Decolonization in Africa". African Affairs. 69 (274): 15. JSTOR 720177. (login required)

- Nissimi, Hilda (2006). "Mau Mau and the Decolonisation of Kenya". Journal of Military and Strategic Studies. 8 (3): 25. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Lowrance-Floyd, Emily (6 April 2012). Losing an Empire, Losing a Role?: The Commonwealth Vision, British Identity, and African Decolonization, 1959–1963 (Ph.D.). University of Kansas. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- Messina, Anthony (1989). Race and Party Competition in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

External links

- Recorded speech in full from BBC Archives

- 1960: Macmillan speaks of 'wind of change' in Africa, BBC News Online: On this day, 3 February 2008.

- "Wind of Change" speech. Analysis from About.com

- Hendrik Verwoerd's response to Harold Macmillan's "Wind of Change" Speech. Full text of Hendrik Verwoerd's response given the same day; from About.com