Winnsboro, South Carolina

Winnsboro is a town in Fairfield County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 3,550 at the 2010 census.[6] It is the county seat of Fairfield County.[7] Winnsboro is part of the Columbia, South Carolina Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Winnsboro, South Carolina | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): "A Town for All Time"[1] | |

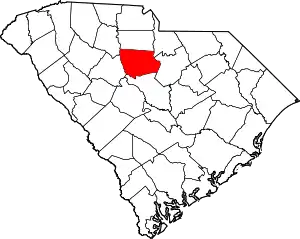

Location of Winnsboro, South Carolina | |

| Coordinates: 34°22′37″N 81°5′17″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | South Carolina |

| County | Fairfield |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.23 sq mi (8.36 km2) |

| • Land | 3.23 sq mi (8.36 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 535 ft (163 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 3,550 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 3,181 |

| • Density | 985.44/sq mi (380.48/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 29180 |

| Area code(s) | 803, 839 |

| FIPS code | 45-78460[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1251474[5] |

| Website | www |

History

Based on archeological evidence, this area of the Piedmont was occupied by various cultures of indigenous peoples from as early as the Archaic period, about 1500 BC. Blair Mound is a nearby archeological site and earthwork likely occupied 1300-1400 AD, as part of the late Mississippian culture in the region.[8]

Several years before the Revolutionary War, Richard Winn from Virginia moved to what is now Fairfield County in the upland or Piedmont area of South Carolina. His lands included the present site of Winnsboro. As early as 1777, the settlement was known as "Winnsborough" since he was the major landowner. His brothers John and Minor Winn joined him there, adding to family founders.

The village was laid out and chartered in 1785 upon petition of Richard and John Winn, and John Vanderhorst. The brothers Richard, John and Minor Winn all served in the Revolutionary War. Richard became a general, and was said to have fought in more battles than any Whig in South Carolina. John gained the rank of colonel. See Fairfield County, South Carolina, for more.

The area was developed for the cultivation of short-staple cotton after Eli Whitney's invention of the cotton gin in 1793, which made processing of this type of cotton profitable. Previously it was considered too labor-intensive. Short-staple cotton was widely cultivated on plantations in upland areas throughout the Deep South, through an interior area that became known as the Black Belt. The increased demand for slave labor resulted in the forced migration of more than one million African-American slaves into the area through sales in the domestic slave market. By the time of the Civil War, the county's population was majority black and majority slave.

Textile mills were constructed in the area beginning in the late 19th century, and originally only whites were allowed to work in the mills. "Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues", an industrial folk song of the 1930s with lyrics typical of the blues, refers to working in a cotton mill in this city. The song arose after the textile mill had been converted to a tire manufacturing plant,[9] reflecting the widespread expansion of the auto industry. The song has been sung by Lead Belly, Pete Seeger, and other artists. It was the basis of one of the ballads by modernist composer/pianist Frederic Rzewski in his Four North American Ballads for solo piano, completed in 1979.[9]

Places listed on the National Register of Historic Places for Winnsboro range from an Archaic period archeological site, to structures and districts spanning the European-American/African-American history of the city, as in the following list: Albion, Balwearie, Blair Mound, Dr. Walter Brice House and Office, Concord Presbyterian Church, Furman Institution Faculty Residence, Hunstanton, Ketchin Building, Bob Lemmon House, Liberty Universalist Church and Feasterville Academy Historic District, McMeekin Rock Shelter, Mount Olivet Presbyterian Church, New Hope A.R.P. Church and Session House, Old Stone House, Rockton and Rion Railroad Historic District, Rural Point, Shivar Springs Bottling Company Cisterns, The Oaks, Tocaland, White Oak Historic District, and the Winnsboro Historic District.[10] Though not listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Winnsboro Town Clock built in 1837 is the oldest continuously running clock in the United States.[11]

In the late 19th century, after white Democrats regained control of state legislatures in the South, they passed Jim Crow laws establishing racial segregation of public facilities and disenfranchising blacks, excluding them from the political system. In 1960 in the United States Supreme Court decision of Boynton v. Virginia, the court ruled that racial segregation was unconstitutional in interstate bus stations, restaurants, bathrooms and on buses, as these were covered by constitutional protections of free interstate commerce.[12] The Civil Rights Movement had begun to use public demonstrations and events to build public awareness.

In 1961, CORE decided to test the bus ruling by sending mixed racial groups of Freedom Riders to ride interstate buses and use facilities in the segregated southern United States to challenge practices related to segregation of buses and bus stations. They intended to travel through the Deep South and end at New Orleans. They were met by increasing violence as they went south. Winnsboro was one of the cities where some Freedom Riders were beaten by local whites and arrested by local officials. One was rescued by a local African-American man while outrunning a white mob.[12]

Geography

Winnsboro is located east of the center of Fairfield County at 34°22′37″N 81°5′17″W (34.377069, -81.087959).[13] U.S. Route 321 and South Carolina Highway 34 bypass the town on the west side. US 321 Business passes through the center of town on Congress Street. US 321 leads north 25 miles (40 km) to Chester and south 28 miles (45 km) to Columbia. SC 34 leads southeast 11 miles (18 km) to Ridgeway and west 36 miles (58 km) to Newberry. SC 200 leads northeast 19 miles (31 km) to Great Falls. The unincorporated community of Winnsboro Mills borders the south side of Winnsboro.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town of Winnsboro has a total area of 3.2 square miles (8.4 km2), all land.[6]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 355 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,124 | 216.6% | |

| 1880 | 1,500 | 33.5% | |

| 1890 | 1,738 | 15.9% | |

| 1900 | 1,765 | 1.6% | |

| 1910 | 1,754 | −0.6% | |

| 1920 | 1,822 | 3.9% | |

| 1930 | 2,344 | 28.6% | |

| 1940 | 3,181 | 35.7% | |

| 1950 | 3,267 | 2.7% | |

| 1960 | 3,479 | 6.5% | |

| 1970 | 3,411 | −2.0% | |

| 1980 | 2,919 | −14.4% | |

| 1990 | 3,475 | 19.0% | |

| 2000 | 3,599 | 3.6% | |

| 2010 | 3,550 | −1.4% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 3,181 | [3] | −10.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

As of the 2010 United States Census,[15] there were 3,550 people, 1,497 households, and 931 families residing in the town. The racial makeup of the town was 60.3% African American, 36.1% White, 0.2% Native American, 0.3% Asian, 0.1% from other races, and 1.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.0% of the population.

As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 3,564 people, 1,454 households, and 984 families residing in the town. The population density was 1,109.6 people per square mile (428.9/km2). There were 1,597 housing units at an average density of 492.4 per square mile (190.3/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 40.29% White, 58.46% African American, 0.31% Asian, 0.33% from other races, and 0.61% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.31% of the population.

There were 1,454 households, out of which 33.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.7% were married couples living together, 25.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.3% were non-families. 29.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 3.04.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 27.8% under the age of 18, 9.5% from 18 to 24, 24.8% from 25 to 44, 21.6% from 45 to 64, and 16.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 80.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 75.1 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $25,094, and the median income for a family was $29,550. Males had a median income of $29,275 versus $18,925 for females. The per capita income for the town was $14,135. About 23.6% of families and 24.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 33.9% of those under age 18 and 14.1% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Winnsboro has a public library, a branch of the Fairfield County Library.[16]

Notable people

- D. Wyatt Aiken (1828–1887), U.S. congressman from South Carolina[17]

- Mike Anderson, Baltimore Ravens running back, formerly of the Denver Broncos where he was named NFL Offensive Rookie of the Year for the 2000 season

- Webster Anderson (1933 – 2003), U.S. Army soldier who received the Medal of Honor, the highest US military award, for his actions in the Vietnam War

- Daniel Bonds, WLTX-TV meteorologist

- John Bratton, Confederate general during the American Civil War; U.S. congressman from South Carolina

- Walter B. Brown, former vice-president of Southern Railway (now Norfolk Southern); political figure in South Carolina legislative government

- Robert Houston Curry (1842-1892), member of the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1888 to 1892; wounded Confederate Army veteran, born near Winnsboro[18][19]

- William Porcher DuBose, priest, theologian, educator in the Episcopal Church, and Civil War veteran

- William Ellison, Jr., born a mixed-race slave April on the plantation of William Ellison (likely his father) near Winnsboro; he was apprenticed as a cotton gin maker and allowed to buy his freedom in 1816. He had his own business and also became a major planter in Sumter County, where he owned 1000 acres by 1860 and numerous slaves to work that land.

- Gordon Glisson, champion jockey in thoroughbred horse racing

- Justin Hobgood, NASCAR driver

- James Hooker, singer/songwriter

- Ellis Johnson, college football coach

- James G. Martin, 70th governor of North Carolina (1985-1993)

- John Hugh Means, 64th governor of South Carolina (1850–1852); signed South Carolina Ordinance of Secession in 1860; killed at Second Battle of Manassas during Civil War

- James Francis Miller, politician who represented Texas in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1883-1886

- Kelly Miller (1863-1939), African-American mathematician, sociologist, essayist, newspaper columnist, and author

- James Milling, professional football player

- Thomas J. Robertson, U.S. senator from South Carolina

- Orlando Ruff, defensive lineman for the New Orleans Saints

- Alex Sanders, former Court of Appeals judge, Lt. Governor candidate, College of Charleston president, and Democratic U.S. Senate candidate; resides in Charleston; related to Thomas family of Ridgeway

- Miriam Stevenson, Miss South Carolina 1953, Miss South Carolina USA 1954, Miss USA 1954, Miss Universe 1954

- Tyler Thigpen, Buffalo Bills quarterback

- Joseph A. Woodward, congressman from South Carolina; son of William Woodward

References

- Official website

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Winnsboro town, South Carolina". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Robert L. Stevenson and George Teague (April 1974). "Blair Mound" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places - Nomination and Inventory. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- Kathryn Woodard, "The Pianist's Body at Work: Mediating Sound and Meaning in Frederic Rzewski's Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues", Sonic Meditations, 2008, at Academia website, accessed 13 November 2014

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Winnsboro Town Clock". SC Picture Project. September 4, 2020.

- Watson, Dylan (August 2, 2011). "Freedom Rides Again". Gambit.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010". Census.gov. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- "South Carolina libraries and archives". SCIWAY. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607-1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

- "Membership in the Louisiana House of Representatives, 1812-2012" (PDF). legis.state.la.us. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 29, 2009. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- "Curry, Robert H." The Political Graveyard. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Winnsboro, South Carolina. |