Witch of Agnesi

In mathematics, the witch of Agnesi (Italian pronunciation: [aɲˈɲeːzi, -eːsi; -ɛːzi]) is a cubic plane curve defined from two diametrically opposite points of a circle. It gets its name from Italian mathematician Maria Gaetana Agnesi, and from a mistranslation of an Italian word for a sailing sheet. Before Agnesi, the same curve was studied by Fermat, Grandi, and Newton.

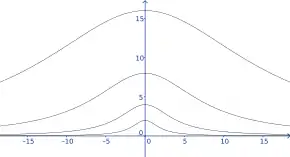

The graph of the derivative of the arctangent function forms an example of the witch of Agnesi. As the probability density function of the Cauchy distribution, the witch of Agnesi has applications in probability theory. It also gives rise to Runge's phenomenon in the approximation of functions by polynomials, has been used to approximate the energy distribution of spectral lines, and models the shape of hills.

The witch is tangent to its defining circle at one of the two defining points, and asymptotic to the tangent line to the circle at the other point. It has a unique vertex (a point of extreme curvature) at the point of tangency with its defining circle, which is also its osculating circle at that point. It also has two finite inflection points and one infinite inflection point. The area between the witch and its asymptotic line is four times the area of the defining circle, and the volume of revolution of the curve around its defining line is twice the volume of the torus of revolution of its defining circle.

Construction

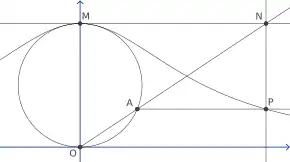

To construct this curve, start with any two points O and M, and draw a circle with OM as diameter. For any other point A on the circle, let N be the point of intersection of the secant line OA and the tangent line at M. Let P be the point of intersection of a line perpendicular to OM through A, and a line parallel to OM through N. Then P lies on the witch of Agnesi. The witch consists of all the points P that can be constructed in this way from the same choice of O and M.[1] It includes, as a limiting case, the point M itself.

Equations

Suppose that point O is at the origin and point M lies on the positive y-axis, and that the circle with diameter OM has radius a. Then the witch constructed from O and M has the Cartesian equation[2][3]

This equation can be simplified, by choosing a = 1/2, to the form

In its simplified form, this curve is the graph of the derivative of the arctangent function.[4]

The witch of Agnesi can also be described by parametric equations whose parameter θ is the angle between OM and OA, measured clockwise:[2][3]

Properties

The main properties of this curve can be derived from integral calculus. The area between the witch and its asymptotic line is four times the area of the fixed circle, .[2][3][5] The volume of revolution of the witch of Agnesi about its asymptote is .[2] This is two times the volume of the torus formed by revolving the defining circle of the witch around the same line.[5]

The curve has a unique vertex at the point of tangency with its defining circle. That is, this point is the only point where the curvature reaches a local minimum or local maximum.[6] The defining circle of the witch is also its osculating circle at the vertex,[7] the unique circle that "kisses" the curve at that point by sharing the same orientation and curvature.[8] Because this is an osculating circle at the vertex of the curve, it has third-order contact with the curve.[9]

The curve has two inflection points, at the points

corresponding to the angles .[2][3] When considered as a curve in the projective plane there is also a third infinite inflection point, at the point where the line at infinity is crossed by the asymptotic line. Because one of its inflection points is infinite, the witch has the minimum possible number of finite real inflection points of any non-singular cubic curve.[10]

The largest area of a rectangle that can be inscribed between the witch and its asymptote is , for a rectangle whose height is the radius of the defining circle and whose width is twice the diameter of the circle.[5]

History

Early studies

.jpg.webp)

The curve was studied by Pierre de Fermat in his 1659 treatise on quadrature. In it, Fermat computes the area under the curve and (without details) claims that the same method extends as well to the cissoid of Diocles. Fermat writes that the curve was suggested to him "ab erudito geometra" [by a learned geometer].[12] Paradís, Pla & Viader (2008) speculate that the geometer who suggested this curve to Fermat might have been Antoine de Laloubère.[13]

The construction given above for this curve was found by Grandi (1718); the same construction was also found earlier by Isaac Newton, but only published posthumously later, in 1779.[14] Grandi (1718) also suggested the name versiera (in Italian) or versoria (in Latin) for the curve. The Latin term is also used for a sheet, the rope which turns the sail, but Grandi may have instead intended merely to refer to the versine function that appeared in his construction.[5][14][15][16]

In 1748, Maria Gaetana Agnesi published Instituzioni analitiche ad uso della gioventù italiana, an early textbook on calculus.[11] In it, after first considering two other curves, she includes a study of this curve. She defines the curve geometrically as the locus of points satisfying a certain proportion, determines its algebraic equation, and finds its vertex, asymptotic line, and inflection points.[17]

Etymology

Maria Gaetana Agnesi named the curve according to Grandi, versiera.[15][17] Coincidentally, at that time in Italy it was common to speak of the Devil, the adversary of God, through other words like aversiero or versiera, derived from Latin adversarius. Versiera, in particular, was used to indicate the wife of the devil, or "witch".[18] Because of this, Cambridge professor John Colson mistranslated the name of the curve as "witch".[19] Different modern works about Agnesi and about the curve suggest slightly different guesses how exactly this mistranslation happened.[20][21] Struik mentions that:[17]

The word [versiera] is derived from Latin vertere, to turn, but is also an abbreviation of Italian avversiera, female devil. Some wit in England once translated it 'witch', and the silly pun is still lovingly preserved in most of our textbooks in English language. ... The curve had already appeared in the writings of Fermat (Oeuvres, I, 279–280; III, 233–234) and of others; the name versiera is from Guido Grandi (Quadratura circuli et hyperbolae, Pisa, 1703). The curve is type 63 in Newton's classification. ... The first to use the term 'witch' in this sense may have been B. Williamson, Integral calculus, 7 (1875), 173;[22] see Oxford English Dictionary.

On the other hand, Stephen Stigler suggests that Grandi himself "may have been indulging in a play on words", a double pun connecting the devil to the versine and the sine function to the shape of the female breast (both of which can be written as "seno" in Italian).[14]

Applications

A scaled version of the curve is the probability density function of the Cauchy distribution. This is the probability distribution on the random variable determined by the following random experiment: for a fixed point above the -axis, choose uniformly at random a line through , and let be the coordinate of the point where this random line crosses the axis. The Cauchy distribution has a peaked distribution visually resembling the normal distribution, but its heavy tails prevent it from having an expected value by the usual definitions, despite its symmetry. In terms of the witch itself, this means that the -coordinate of the centroid of the region between the curve and its asymptotic line is not well-defined, despite this region's symmetry and finite area.[14][23]

In numerical analysis, when approximating functions using polynomial interpolation with equally spaced interpolation points, it may be the case for some functions that using more points creates worse approximations, so that the interpolation diverges from the function it is trying to approximate rather than converging to it. This paradoxical behavior is called Runge's phenomenon. It was first discovered by Carl David Tolmé Runge for Runge's function , another scaled version of the witch of Agnesi, when interpolating this function over the interval . The same phenomenon occurs for the witch itself over the wider interval .[24]

The witch of Agnesi approximates the spectral energy distribution of spectral lines, particularly X-ray lines.[25]

The cross-section of a smooth hill has a similar shape to the witch.[26] Curves with this shape have been used as the generic topographic obstacle in a flow in mathematical modeling.[27][28] Solitary waves in deep water can also take this shape.[29][30]

A version of this curve was used by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz to derive the Leibniz formula for π. This formula, the infinite series

can be derived by equating the area under the curve with the integral of the function , using the Taylor series expansion of this function as the infinite geometric series , and integrating term-by-term.[3]

In popular culture

The Witch of Agnesi is the title of a novel by Robert Spiller. It includes a scene in which a teacher gives a version of the history of the term.[31]

Witch of Agnesi is also the title of a music album by jazz quartet Radius. The cover of the album features an image of the construction of the witch.[32]

Notes

- Eagles, Thomas Henry (1885), "The Witch of Agnesi", Constructive Geometry of Plane Curves: With Numerous Examples, Macmillan and Company, pp. 313–314

- Lawrence, J. Dennis (2013), "4.3 Witch of Agnesi (Fermat, 1666; Agnesi, 1748)", A Catalog of Special Plane Curves, Dover Books on Mathematics, Courier Corporation, pp. 90–93, ISBN 9780486167664

- Yates, Robert C. (1954), "Witch of Agnesi", Curves and their Properties (PDF), Classics in Mathematics Education, 4, National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, pp. 237–238

- Cohen, David W.; Henle, James M. (2005), Calculus: The Language of Change, Jones & Bartlett Learning, p. 351, ISBN 9780763729479

- Larsen, Harold D. (January 1946), "The Witch of Agnesi", School Science and Mathematics, 46 (1): 57–62, doi:10.1111/j.1949-8594.1946.tb04418.x

- Gibson, C. G. (2001), Elementary Geometry of Differentiable Curves: An Undergraduate Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Exercise 9.1.9, p. 131, doi:10.1017/CBO9781139173377, ISBN 0-521-80453-1, MR 1855907

- Haftendorn, Dörte (2017), "4.1 Versiera, die Hexenkurve", Kurven erkunden und verstehen (in German), Springer, pp. 79–91, doi:10.1007/978-3-658-14749-5, ISBN 978-3-658-14748-8. For the osculating circle, see in particular p. 81: "Der erzeugende Kreis ist der Krümmungskreis der weiten Versiera in ihrem Scheitel."

- Lipsman, Ronald L.; Rosenberg, Jonathan M. (2017), Multivariable Calculus with MATLAB®: With Applications to Geometry and Physics, Springer, p. 42, ISBN 9783319650708,

The circle "kisses" the curve accurately to second order, thus is given the name osculating circle (from the Latin word for "kissing").

- Fuchs, Dmitry; Tabachnikov, Serge (2007), Mathematical Omnibus: Thirty Lectures on Classic Mathematics, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, p. 142, doi:10.1090/mbk/046, ISBN 978-0-8218-4316-1, MR 2350979

- Arnold, V. I. (2005), "The principle of topological economy in algebraic geometry", Surveys in modern mathematics, London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series, 321, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 13–23, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511614156.003, MR 2166922. See in particular pp. 15–16.

- Agnesi, Maria Gaetana (1748), Instituzioni analitiche ad uso della gioventú italiana See in particular Problem 3, pp. 380–382, and Fig. 135.

- de Fermat, Pierre (1891), Oevres (in Latin), 1, Gauthier-Villars et fils, pp. 280–285

- Paradís, Jaume; Pla, Josep; Viader, Pelegrí (2008), "Fermat's method of quadrature", Revue d'Histoire des Mathématiques, 14 (1): 5–51, MR 2493381

- Stigler, Stephen M. (August 1974), "Studies in the History of Probability and Statistics. XXXIII. Cauchy and the Witch of Agnesi: An Historical Note on the Cauchy Distribution", Biometrika, 61 (2): 375–380, doi:10.1093/biomet/61.2.375, JSTOR 2334368, MR 0370838

- Truesdell, C. (1991), "Correction and Additions for "Maria Gaetana Agnesi"", Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 43 (4): 385–386, doi:10.1007/BF00374764,

[…] nata da' seni versi, che da me suole chiamarsi la Versiera in latino però Versoria […]

- Grandi, G. (1718), "Note al trattato del Galileo del moto naturale accellerato", Opera Di Galileo Galilei (in Italian), III, Florence, p. 393. As cited by Stigler (1974).

- A translation of Agnesi's work on this curve can be found in: Struik, Dirk J. (1969), A Source Book in Mathematics, 1200–1800, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, pp. 178–180

- Pietro Fanfani, Vocabolario dell'uso toscano, p. 334

- Mulcrone, T. F. (1957), "The names of the curve of Agnesi", American Mathematical Monthly, 64 (5): 359–361, doi:10.2307/2309605, JSTOR 2309605, MR 0085163

- Singh, Simon (1997), Fermat's Enigma: The Epic Quest to Solve the World's Greatest Mathematical Problem, New York: Walker and Company, p. 100, ISBN 0-8027-1331-9, MR 1491363

- Darling, David (2004), The Universal Book of Mathematics: From Abracadabra to Zeno's Paradoxes, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, p. 8, ISBN 0-471-27047-4, MR 2078978

- Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2018, witch, n.2, 4(e), retrieved 3 July 2018,

1875 B. Williamson Elem. Treat. Integral Calculus vii. 173 Find the area between the witch of Agnesi and its asymptote.

- Alexander, J. McKenzie (2012), "Decision theory meets the Witch of Agnesi", Journal of Philosophy, 109 (12): 712–727, doi:10.5840/jphil20121091233

- Cupillari, Antonella; DeThomas, Elizabeth (Spring 2007), "Unmasking the witchy behavior of the Runge function", Mathematics and Computer Education, 41 (2): 143–156, ProQuest 235858817

- Spencer, Roy C. (September 1940), "Properties of the Witch of Agnesi—Application to Fitting the Shapes of Spectral Lines", Journal of the Optical Society of America, 30 (9): 415, Bibcode:1940JOSA...30..415S, doi:10.1364/josa.30.000415

- Coppin, P. A.; Bradley, E. F.; Finnigan, J. J. (April 1994), "Measurements of flow over an elongated ridge and its thermal stability dependence: The mean field", Boundary-Layer Meteorology, 69 (1–2): 173–199, Bibcode:1994BoLMe..69..173C, doi:10.1007/bf00713302,

A useful general form for the hill shape is the so-called 'Witch of Agnesi' profile

- Snyder, William H.; Thompson, Roger S.; Eskridge, Robert E.; Lawson, Robert E.; Castro, Ian P.; Lee, J. T.; Hunt, Julian C. R.; Ogawa, Yasushi (March 1985), "The structure of strongly stratified flow over hills: dividing-streamline concept", Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 152 (–1): 249, Bibcode:1985JFM...152..249S, doi:10.1017/s0022112085000684

- Lamb, Kevin G. (February 1994), "Numerical simulations of stratified inviscid flow over a smooth obstacle" (PDF), Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 260 (–1): 1, Bibcode:1994JFM...260....1L, doi:10.1017/s0022112094003411, archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2014

- Benjamin, T. Brooke (September 1967), "Internal waves of permanent form in fluids of great depth", Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 29 (3): 559, Bibcode:1967JFM....29..559B, doi:10.1017/s002211206700103x

- Noonan, Julie A.; Smith, Roger K. (September 1985), "Linear and weakly nonlinear internal wave theories applied to 'morning glory' waves", Geophysical & Astrophysical Fluid Dynamics, 33 (1–4): 123–143, Bibcode:1985GApFD..33..123N, doi:10.1080/03091928508245426

- Phillips, Dave (12 September 2006), "Local teacher, author figures math into books", The Gazette

- Radius – Witch Of Agnesi (Plutonium Records, 2002), Discogs, retrieved 28 May 2018

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Witch of Agnesi. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Witch of Agnesi. |

- "Witch of Agnesi" at MacTutor's Famous Curves Index

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Witch of Agnesi", MathWorld

- Witch of Agnesi by Chris Boucher based on work by Eric W. Weisstein, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- "Witch of Agnesi" at "mathcurve"

- Lamb, Evelyn (28 May 2018), "A Few of My Favorite Spaces: The Witch of Agnesi", Roots of Unity, Scientific American