Witchcraft in early modern Britain

Witch trials and witch related accusations were at a high during the early modern period in Britain, a time that spanned from the beginning of the 16th century to the end of the 18th century.

Witchcraft in this article refers to any magical or supernatural practices made by mankind. Prior to it being made a capital offence in 1542.[1] it was often seen as a healing art, performed by people referred to as the cunning folk, whereas it was later believed to be Satanic in origin[2] and thus sparked a series of laws being passed and trials being conducted.

Belief in witchcraft

The belief in magic and magical practices has been documented in Britain all the way back until antiquity – the belief that people could have influence over or make predictions about the natural world did not arise only in the 16th century.

Alleged practices

There were thought to be many types of witchcraft that one could practice, such as alchemy; the purification, perfection, maturation and changing of various substances,[3] and astrology; the reading of the heavens to predict one’s future, however in the early modern period the most concern was over that which involved dealing with the devil.[2] Witches were said to make pacts with the devil in exchange for powers, belief and prosecution of witchcraft in Scotland was especially focused on the demonic pact.

Witches no longer were seen as healers or helpers, but rather were believed to be the cause of many natural[4] and man-made disasters. Witches were blamed for troubles with livestock, any unknown diseases and unpredicted weather changes.[5]

The first witch condemned in Ireland, Lady Alice Kyteler, was accused of such practices as animal sacrifice, creating potions to control others and possessing a familiar[6] (an animal companion often thought to be possessed by a spirit which aided a witch in her magic).

Prevalence of belief

It was not just common folk that believed in the existence of witches and magic, but Royals and the Church as well. Henry VIII changed the face of religion in Britain, and it was common belief that this allowed for dark or satanic forces to arise.[7] As a result a law was passed[1] which defined what it was to be a witch and how they must be prosecuted.

However, not everyone was convinced. A member of parliament in England called Reginald Scot wrote a book called The Discoverie of Witchcraft which in part presented his belief that Britain had been fooled into believing in witchcraft by easily explained tricks. The book's success was widespread, but his scepticism in regards to magic was not what drew in most of its admirers; The Discoverie of Witchcraft also contained details regarding the belief in and practices of witches - it held sections on alchemy, spirits and conjuring, much of which is thought to have inspired Shakespeare's descriptions of the witches in Macbeth[8]

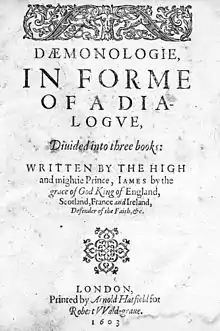

Another book which was thought to play a part in the creation of Macbeth was Daemonologie by King James VI of Scotland. A stark contrast to that of Scot, King James VI was a firm believer in magic and the role of demons in its practice. His book acts as a dissertation on the practice of necromancy, divination and dark magic and how demons seek to influence weakened men and women and convince them to take part in the unholy practice of magic.[9] It was in essence published to inform the general population of Scotland about why witches must be hunted and prosecuted.

Witch hunts and trials

Wales

Compared to the rest of Britain, Wales had relatively few trials or hunts for witches during the early modern period. Many accusations were made, but finding proof made convicting women as witches rather difficult.[10] The first witch to be trialled and executed in Wales[10] was Gwen ferch Ellis of Llandyrnog. She was accused of using a poppet (a figurine fashioned to look like a specific person, used for spell casting) and casting a destructive charm. Charms were common in this time and often used for healing,[11] an art which Gwen herself took part in, however this specific charm was written backwards and as per the traditions of the time this meant that it was meant for harm.[10]

Scotland

Between the years of 1500 and 1700 somewhere between 4000 and 6000 people were tried for witchcraft in Scotland, a much higher number than any of the other British countries attained. This was likely due to the reign of King James VI who was known for his interest in sorcery and magic. He was even documented as having overseen trials and torture of multiple women accused of witchcraft.[12] Following the Scotland's union with England 1707[13] prosecutions of witches declined as they were more tightly controlled by specific magic related laws.

One of Scotland's most notable mass witch trials occurred under the reign and supervision of King James VI. The trials took place in North Berwick between the years of 1590 and 1592, and led to at least 70 accused witches being condemned to violent torture and in most cases, death. The trials took place after the King experienced terrible storms whilst journeying by ship to Denmark where he would marry Princess Anne. King James VI, having seen authorities in Denmark accuse women such as Anna Kolding of using witchcraft to create the storms, turned to the "witches" in North Berwick to blame for this event.[14] Most of the information we have on the North Berwick trials was found in the King's book Daemonologie, as well as a pamphlet entitled Newes from Scotland that was published in London. The trials were infamous in their time, and were known to have influenced Shakespeare's Macbeth. The play borrows the setting of the trials and draws on many of the witches confessed practices, the witches also reference the storm during King James VI's crossing to Denmark in their spell:

"Purposely to be cassin into the sea to raise winds for destruction of ships."[15]

England

The death toll in England was significantly lower than that of Scotland,[16] but many notable trials still occurred due to a number of self-proclaimed "witch-hunters". One such witch-hunter was a man from East Anglia, Matthew Hopkins, who called himself the "Witchfinder General".[17] Hopkins and his associates were believed to have caused the executions of at least 300 accused men and women.[18]

One of the more well known trials was that of the Witches of Belvoir, which implicated three women; Joan Flowers, and Margaret and Philippa Flowers, who were her two daughters. The three were known locally to be herbal healers,[19] and following their dismissal as servants from the Castle of Belvoir the Earl and two of his sons died whilst the Countess and her daughter suffered from violent illness.[20] It was five years after these events, and after the hanging of a group of witches in Leicestershire,[21] that the Flowers were arrested on suspicion of harming the Earl of Rutland's family through sorcery. Joan Flowers died on the way to her trial after consuming communion bread.[22] Her daughters confessed to having familiars, to having visions of demons and to performing a spell on the Earl and Countess' children.[23] Margaret was hung at Lincoln Castle on the 11th of March 1619, whereas her sister managed to escape, presumably by drugging the guards.[19]

The last documented executions of witches in England occurred during the Bideford witch trial in Devon. Three women were hanged for the crime of causing a local woman, Grace Thomas, to fall ill by supernatural means. There was a great deal of other accusations that also contributed to their being found guilty, although none of which had any evidence.[24] The women that were hanged were Temperance Lloyd; a widow, Mary Trembles; a beggar, and Susanna Edwards; another beggar.

Ireland

Unlike the mass trials and executions found across the rest of the UK, and even the rest of Europe during the early modern period, Ireland's number of prosecutions failed to reach even double figures.[25] It has been suggested that this is due to the lack of religious upheaval in Ireland during this time,[26] it has also been suggested by Ireland's general population[27] that this fact may be due to their strong cultural belief in the Sidhe, more commonly known as fairies, which were known for causing trouble and general mischief which in other countries was linked to witchcraft (e.g. the curdling of milk, dying of crops etc.[5]). Nevertheless there were still a series of notable trials that occurred, the first of which was Lady Alice Kyteler (described above) and her maidservant Petronilla de Meath, who was tortured and forced into confessing them both to be witches which led to them being burnt at the stake.[28] Another well documented witch trial occurred in March 1711 where eight women were convicted and sentenced to death for the practice of witchcraft in Islandmagee, an area of strong Scottish-English heritage, which Dr. Andrew Sneddon suggests may be a cause for its large scale.[25]

Theories

The Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age was a period of dramatic climate change that took place around the early modern period, which in Britain was characterised by cool, rainy and torrential weather as well as a growth in mountain glaciers. The effects of this weather were drastic - crops began to fail, livestock didn't produce enough milk or meat and people fell ill.[29] During this time there was no knowledge of climate change and little rational explanation could be found, so it is believed by the German historian Wolfgang Behringer, and many other notable historians, that in their desperation for a solution and explanation, the people of Britain (and Europe as a whole) blamed it on witchcraft.[30] Older women of the lower classes were the easiest to blame, with little societal standing to defend themselves, and so often fell victim to witch related accusations.

Religion

It wasn't until the beginning of the 16th century that the Church and the State recognised witchcraft as a legitimate practice, this was in a time of great religious conflict in Britain, and many historians have theorised that these two events are connected.

Peter Leeson and Jacob Russ argue that the rise of witch hunts following a period in which the Church refused to acknowledge their existence (despite their popular belief in medieval Britain) was due to a competition between the Protestant and Catholic churches who were both seeking higher numbers of followers.[26] These two economists describe this process as a non-price competition, and claim that this serves as an explanation for Ireland's low number of witch trials[25] - the country remained strongly Catholic even after the Reformation.

Politics

In Peter Elmer's novel Witchcraft, Witch-Hunting, and politics in early modern England[31] he argues and provides evidence for the fact that many of England's great witch trials occurred at times when political parties and governing bodies felt that their authority was being threatened. During the years of 1629 to 1637 no trials occurred in Dorchester, it is theorised in Elmer's book that this is because the government of that area was prosperous and felt their order was secure.

In a paper by Albert James Bergesen, an American sociologist, a theory is proposed that witch hunts, across all countries, were merely a tool used by the government to bring communities together by giving them a common enemy and then increasing their faith in the governing body by providing them with a method to get rid of said enemy.[32]

See also

References

- "Witchcraft". UK Parliament. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- Scarre, Geoffrey (1987). Witchcraft and magic in sixteenth and seventeenth-century Europe. Basingstoke: Macmillan Education. ISBN 0333399331. OCLC 14904269.

- "Alchemy - Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy". www.rep.routledge.com. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- Behringer, Wolfgang (1999), "Climatic Change and Witch-Hunting: The Impact of the Little Ice Age on Mentalities", Climatic Variability in Sixteenth-Century Europe and Its Social Dimension, Springer Netherlands, pp. 335–351, doi:10.1007/978-94-015-9259-8_13, ISBN 9789048153060

- "Little Ice Age", Wikipedia, 2019-04-17, retrieved 2019-05-08

- "The Sorcery Trial of Alice kyteler by Bernadette Williams". History Ireland. 2013-01-24. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- Gaskill, M. (2008-02-01). "Witchcraft and Evidence in Early Modern England". Past & Present. 198 (1): 33–70. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtm048. ISSN 0031-2746.

- "The Discovery of Witchcraft by Reginald Scot, 1584". The British Library. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- Pumfrey, Stephen (2003-01-02), "Potts, plots and politics: James I's Daemonologie and The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches", The Lancashire Witches, Manchester University Press, pp. 22–39, doi:10.7228/manchester/9780719062032.003.0002, ISBN 9780719062032

- "BBC - Wales History: Welsh witches". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- "Written Charms". Apotropaios. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- Keay, John; Keay, Julia (1994). Collins encyclopaedia of Scotland. Hammersmith, London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0002550822. OCLC 33166697.

- "The Act of Union between England and Scotland". Historic UK. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- William Monter (2008). "Fiscal Sources and Witch Trials in Lorraine". Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft. 2 (1): 21–48. doi:10.1353/mrw.0.0015. ISSN 1940-5111. S2CID 161615132.

- Kushner, David Z. (2002). Macbeth (iii). Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.o903140.

- Levack, Brian P. (1995). The witch-hunt in early modern Europe (2nd ed.). London: Longman. ISBN 058208069X. OCLC 30154582.

- Gaskill, Malcolm (2005). Witchfinders : a seventeenth-century English tragedy. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674019768. OCLC 60589143.

- Poole, Robert (2002). The Lancashire witches : histories and stories. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 1417574771. OCLC 57555447.

- "Witchcraft trio 'may have been framed'". 2013-10-31. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- Pringle, Denys (2003). Belvoir Castle [Coquet Castle; Arab. Kawkab al-Hawā, Kaukab el Hawā; now Heb. Kôkhov ha-Yardēn, Kokhav Hayarden]. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t007763.

- Westwood, Jennifer (2005). The lore of the land : a guide to England's legends, from spring-heeled Jack to the Witches of Warboys. Penguin. ISBN 9780141007113. OCLC 61302120.

- Borman, Tracy (2014). Witches : a tale of sorcery, scandal and seduction. Thorpe. ISBN 9781444821253. OCLC 892871089.

- "Witches of Belvoir Witches Trials (England, 1618 - 1619) - Witchcraft". www.witchcraftandwitches.com. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- "The Trial of the Bideford Witches", Witchcraft and Demonology in South-West England, 1640-1789, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, doi:10.1057/9780230361386.0006, ISBN 9780230361386

- Sneddon, Andrew (December 2012). "Witchcraft Belief and Trials in Early Modern Ireland". Irish Economic and Social History. 39 (1): 1–25. doi:10.7227/iesh.39.1.1. ISSN 0332-4893. S2CID 161411162.

- Leeson, Peter T.; Russ, Jacob W. (2017-08-16). "Witch Trials". The Economic Journal. 128 (613): 2066–2105. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12498. ISSN 0013-0133. S2CID 219395432.

- "Why Were There Only a Few Irish Witch Trials?". Lora O'Brien - Irish Author & Guide. 2018-02-07. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- Wright, Thomas (2012), "Story of the lady Alice Kyteler", Narratives of Sorcery and Magic, Cambridge University Press, pp. 25–40, doi:10.1017/cbo9781139176354.002, ISBN 9781139176354

- "Little Ice Age | geochronology". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- Behringer, Wolfgang (1999), "Climatic Change and Witch-Hunting: The Impact of the Little Ice Age on Mentalities", Climatic Variability in Sixteenth-Century Europe and Its Social Dimension, Springer Netherlands, pp. 335–351, doi:10.1007/978-94-015-9259-8_13, ISBN 9789048153060

- Elmer, Peter (2016). Witchcraft, witch-hunting, and politics in early modern England. ISBN 9780198717720. OCLC 915508933.

- Bergesen, Albert James (April 1977). "Political Witch Hunts: The Sacred and the Subversive in Cross-National Perspective". American Sociological Review. 42 (2): 220–233. doi:10.2307/2094602. ISSN 0003-1224. JSTOR 2094602.