Witoto

The Witoto (also Huitoto or Uitota) are an indigenous people in southeastern Colombia and northern Peru.[3]

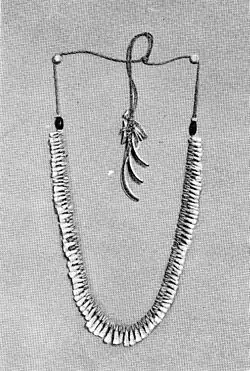

Huitoto necklace, c. 1924 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 8,500[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Witotoan languages: Ocaina language (oca), Witoto Proper: Minica Huitoto (hto), Murui Huitoto (huu), Nüpode (hux)[2] | |

| Religion | |

| traditional tribal religion |

History

The Witoto first experienced contact with Europeans at the beginning of the 17th century. However, contact remained sporadic into the 19th century.[4]

The Witoto people were once composed of 100 villages or 31 tribes, but disease and conflict have reduced their numbers. At the early 20th century, Witoto population was 50,000. The rubber boom in the mid-20th century brought diseases and displacement to the Witotos, causing their numbers to plummet to 7,000–10,000.[1] The rubber boom also increased outside interest in the caucho extraction due to the surge in production and demand. In the Witoto region, Julio Cesar Arana was one of the main figures of the rubber industry. He founded the Peruvian Amazonian Company, a business that extracted and sold Amazonian caucho rubber.[5] The company relied on indigenous, including Witoto, labor, and he kept his workers in unending servitude through constant debt and physical torture. [6] His practices had such a large negative impact on the surrounding indigenous nations that, by the time the company’s work ended, indigenous populations in the area had declined by more than half of their original numbers.[7]

Since the 1990s, cattle ranchers have invaded Witoto lands, depleted the soil, and polluted the waterways. In response to the incursions, the Colombian government established several reservations for Witotos.[1]

Subsistence

Witoto peoples practice swidden or slash-and-burn agriculture. To prevent depleting the land, they relocate their fields every few yields. Major crops include cacao, coca, maize, bitter and sweet manioc, bananas, mangoes, palms, pineapples, plaintains, sugar cane, sweet potatoes, and yams. Tobacco and peanuts are also cultivated in small quantities. Ethnobotanists have studied Witoto agriculture due to its efficiency and sustainability.[1]

Culture

Traditionally the Witoto are divided into a number of groups. The largest group are the Murui, who live on the western end of their historical territory. Another group, the Muinane, traditionally lived to the east of the Murui. Historically they were a large group but most were gradually absorbed into the Murui. A third group, the Meneca, live in the Putumayo and Ampiyacu riversheds. There are also a number of significantly smaller groups.[4]

Traditionally, the Witoto people lived according to their patrilineal lineage. This practice is less common today, although some elders in the community continue the tradition. They live in communal houses known as joforomo or maloca that several families share. Every family has an independent sector where they can hang their hammocks. Their diets consist mainly of Casabe, arepas made with yuca brava flour, and protein from hunting and fishing.

_(20239075598).jpg.webp)

In their maloca, men have a specific place where they can consume an ancestral green powder called mambe, or jiibie. This powder is made from coca leaves and the ashes of yarumo.

Traditionally, when Witoto men consume mambe they play drums called Maguare, which can be heard kilometers away. The purpose of these drums are to communicate with nearby tribes.

Notes

- "Witoto." Countries and Their Cultures. Retrieved 6 Dec 2011.

- "Language Family Trees: Witotoan, Witoto." Ethnologue. Retrieved 6 Dec 2011.

- "Witoto." Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 Dec 2011.

- Olson, James Stuart (1991). The Indians of Central and South America: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 399–400. ISBN 0313263876.

- Vargas Álvarez, Sebastián (2017-12-31). "Desmontando imágenes de diferencia. Representaciones de lo indígena en las conmemoraciones nacionales latinoamericanas". Memoria y Sociedad. 21 (43). doi:10.11144/javeriana.mys21-43.didr. ISSN 2248-6992.

- Santamaría, Angela (2017-09-02). "Memory and resilience among Uitoto women: closed baskets and gentle words to invoke the pain of the Colombian Amazon". Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies. 12 (3): 315–330. doi:10.1080/17442222.2017.1363352. ISSN 1744-2222.

- República, Subgerencia Cultural del Banco de la. "La Red Cultural del Banco de la República". www.banrepcultural.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology (1901). Bulletin. Smithsonian Libraries. Washington : G.P.O.

- República, Subgerencia Cultural del Banco de la. "La Red Cultural del Banco de la República". www.banrepcultural.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-05-08.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Witoto people. |

- "Huitoto Tribe in Colombia Teaches its Native Language", Indian Country Today