Women's suffrage in Francoist Spain and the democratic transition

Women's suffrage in Francoist Spain and the democratic transition was constrained by age limits, definitions around heads of household and a lack of elections. Women earned the right to vote in Spain in 1933 as a result of legal changes made during the Second Spanish Republic. Women lost most of their rights after Franco came to power in 1939 at the end of the Spanish Civil War, with the major exception that women did not universally lose their right to vote. Repression of the women's vote occurred nevertheless as the dictatorship held no national democratic elections between 1939 and 1977.

| Part of a series on |

| Francoism |

|---|

Eagle of Saint John |

|

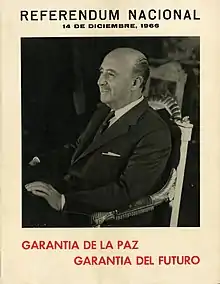

The Franco regime imposed changes around women's suffrage, namely as it related to the need for women to be heads of household and around women's age of majority. Originally, the age was 23, but this was reduced to 21 in 1943 provided women were no longer living with their parents; otherwise the age of majority was 25. Several national referendums were held in Spain, where women could vote if they were over the age of 21, for example in 1942, 1947 and 1966. Women could, under certain conditions involving age and marital status, vote in municipal elections. They could also run in municipal elections. Dolores Pérez Lapeña was one such women, winning in Valladolid in the 1963 elections.

The first national elections in which women could vote took place in 1977, two years after the death of Franco. Despite this, there were legal ambiguities in the democratic transition period over married women's right to vote as Article 57 of the Civil Code said women needed to obey their husbands. It was not clear if this applied to their voting rights until 1981.

History

Francoist period (1939–1975)

The first time all Spanish women could vote in elections for the national legislature was on 19 November 1933 during the Second Spanish Republic. These women would only be able to vote in national elections one more time, in 1936. This period ended with the Spanish Civil War and the official start of Francoist Spain in 1939.[1] Between 1939 and 1976, the opportunities to vote on the national level were nearly non-existent in Spain. There were three national referendums, and two elections for attorneys to represent families in the courts. There were also eight municipal elections. Because of controls by the dictatorship, elected municipal and legislative officials were limited in the changes they could enact.[2]

Women nominally maintained the right to vote, one of the few rights carried over from the Second Republic to the Francoist period.[3] Universal suffrage existed in Spain during the dictatorship, but the only time people could vote was during referendums and for municipal officials. While direct voting was allowed, repression of women still existed as only the head of household could vote. This largely excluded women, as only widowed women were generally considered heads of household.[4] Women's suffrage also changed because of rules around the age of majority and the voting age.[5][6] The age of majority for women became 23 as a result of the imposition of the reintroduction of the Civil Code of 1889, Article 321. This changed in 1943, when the age of majority was lowered to 21 so as to be consistent for both genders. An additional clause still stipulated women did not reach majority until they were 25 unless they were married or joined a convent. No elections or referendums took place in the period between 1939 and 1944; despite legal changes in the age of majority, women continued to be disenfranchised as the dictatorship did not hold elections.[5] The voting age for women appeared to change again in 1945, when the age for some women was lowered to 18. According to Article 5 of the Decree of 29 September 1945, voters included, "Spaniards, neighbors and people over 21 years, or emancipated people over the age of 18, men or women, under whose dependence other persons coexist in the same home."[6] Most public efforts around franchising of women in this period were based on regime attempts to be perceived abroad as more democratic, and did not necessarily lead to greater numbers of eligible voters or meaningful and free elections that could result in undermining the regime.[7]

The Cortes Españolas was created in 1942, to act as a pseudo-representational body. Selection for the body was done indirectly, through other political organs of the state, including state-sanctioned unions, city councils and state-run businesses.[4] The 1942 Referendum Act stated in Article 2, "The referendum will be held among all the men and women of the Nation over twenty-one years [...]"[7]

Municipal elections entailed three categories. These included union elections, corporate and entities, and family representatives.[6] The first municipal union elections took place in 1944. The union elections of 1944 were broadly boycotted by many union workers who were skeptical of the regime's actions. These elections were controlled by Franco through the right-wing Falange. UGT and CNT continued to boycott union elections into the 1950s and 1960s, as they saw them as legitimizing the regime.[4] Elections were not a threat to the regime as they had control over who could run. The regime's continuing was assured as Emilio Lamo de Espinosa, civil governor of Málaga, explained saying that it had been created "by the effort of a war and only an action of equal but opposite meaning can ruin our political continuity."[4] Alejandra Bujedo Fernández and María Pilar Zarzuela Plaza were the first female candidates for a municipal union election in Valladolid but they did not run until 1970, and were joined by Esperanza López Delgado who ran for one of three corporations and entities positions.[6]

A referendum on the Succession Law of 1947 was held, with women being allowed to vote.[4][8] The new law prohibited women from being allowed to succeed the Spanish throne.[8] Voter turnout was alleged by the regime to be 100%.[4]

Madrid held municipal elections in 1948, the first such elections since the end of the Civil War. Only heads of household could vote, which disenfranchised most women. Voters had few options, all of them involving right-wing candidates, mostly Falangists, who belonged to official parties or who were unofficial candidates. Records show there was an abstention rate of 40%.[4]

The Madrid municipal elections of 1954 had the same conditions as 1948 for voting. The candidates were primarily made up of official party candidates and monarchists who had become disconnected from the regime. While allowing these right wing monarchists to run, the Government used all its available tools to discourage voters from supporting them. Voter abstention in these elections was 67%. The votes for the official party candidates ranged between 7,000 and 22,000 while the highest number of votes for a monarchist candidate was 7,600.[4]

The 1963 municipal elections for corporations and entities positions in Valladolid saw Dolores Pérez Lapeña come out victorious.[6][9] Only three people were elected into this position, and she won along with Rafael Tejedor Torcida and Juan Ignacio Pérez Pellón. It was the first time since the Spanish Second Republic that a woman had been elected to office in the city. She told the local newspaper, El Norte de Castilla, at the time, "For the first time, women have to be represented in their thoughts and concerns before their City Council by another woman." [9] Her concerns as an elected official included "displacement from the towns before the industrial growth of the city." They also concerned "her daily concerns [about the woman] of the market, her situation in some distant places, its supply, transport."[9] She would win again in the 1966 elections.[6][9] María Teresa Íñigo de Toro and Pérez Lapeña also ran in those elections, with Pérez Lapeña emerging victorious.[9]

The 1966 Spanish organic law referendum gave universal suffrage to all citizens over the age of 21.[10] Citizens were so confused about who could vote in this election, that a newspaper needed to explain, stating: "All Spanish citizens over twenty-one years of age, without distinction of sex, state or profession, have the right and obligation to take part in the referendum vote, freely casting the ballot for or against the legislative draft consulted."[11] This referendum was little more than the regime trying to get the electorate to support its policies while appearing more democratic. Among the people who went to the polls were 103-year-old Benigna Medrano from Avila and groups of cloistered nuns.[11] In the 1966 referendum in Alicante, some districts with high numbers of older people and women had lower turnout rates than younger districts with more male voters.[7]

The 1967 Law on Family Representation allowed women to vote, but only if they were the head of their household.[12] Voter turnout was alleged by the regime to be 90%.[4] Sección Feminina played a critical role in advancing changes to the 1955 Ley de Regimen Local about the role of married women in 1968. Consequently, married women were allowed to vote and run in local elections.[13] Married women would get the right to vote in national referendums in 1970.[6]

The 1967 municipal elections were the first to allow direct election. In Madrid, the election was again dominated by Falangist candidates, and politically rebellious Francoists. The abstention rate was 44.3%.[4] Municipal elections also took place in 1970 and 1973.[4] The 1971 Madrid municipal elections had an abstention rate of 68.3%, higher than the national average of 50%. Voters in the region were extremely skeptical of the regime, and did not turn out. Abstention for many voters was a way of expressing anti-Francoist sentiment.[4]

Law 31/1972 changed in respect to Articles 320 and 321. It reduced the age of majority to 21 in all cases for women, and allowed women to act as an adult in civil life. Article 320 now read, "The oldest age begins at 21 years of age. The adult is capable of all acts of civil life, apart from the exceptions established in special cases of this Code."[5]

Democratic transition period (1975–1986)

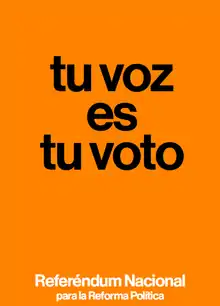

The first national elections held in Spain following the death of Franco in 1975 took place in 1977. For the first time since the Second Spanish Republic, women were fully franchised. For many women, these elections were a hopeful moment and represented a milestone in the democratic transition. Many felt that they had been neglected for too long by the state.[14][1] A referendum was held in 1976 over the proposed 1977 Political Reform Act.[4][15] 77.8% of heads of households voted, with 94.17% voting in favor.[15] In Madrid, 22% of voters submitted blank ballots or null votes, higher than most other regional capitals.[4] Spaniards between 18 and 21 years of age were not eligible to vote. The 1945 national referendum voting rules were applied, with both men and women being allowed to vote.[16][17]

On 16 November 1978, Royal Decree-Law 33/1978 modified the age of majority for all women, with Article 320 then stating, "The age of majority begins for all Spaniards at eighteen years of age." This was reaffirmed in the 1978 Spanish Constitution in Articles 12 and 14. Article 14 gave men and women full legal equality under the law. Article 12 confirmed an age of majority and voting age of 18 for everyone.[5]

No women took part directly in writing the new Spanish constitution, so gender discrimination continued to exist within Spanish law.[18] The 1978 Constitution and the Spanish Civil Code enshrined discrimination against women, specifically against married women. Article 57 of the Civil Code stated, "The husband must protect the woman, and she must obey the husband." This was viewed as conflicting with Article 322 of the Civil Code which stated, "The adult is capable for all acts of civil life, apart from the exceptions established in special cases by this Code." There were other questions about what this implied, and if it meant women were obligated to obey their husbands when it came to how they should vote.[5] The Cortes made changes in the Civil Code in 1981, but none explicitly addressed the issue of whether women were obligated to vote as their husbands told them.[5][19][18] These changes in 1981 did however make it explicit that men and women were equal in marriage and allowed women the ability to divorce their husbands.[18]

References

- "¿Cuándo votaron por primera vez las españolas?". MuyHistoria.es (in Spanish). 2019-02-12. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- País, Ediciones El (1977-08-23). "Tribuna | Las elecciones del franquismo". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- "LA MUJER DURANTE EL FRANQUISMO". Biblioteca Gonzalo de Berceo (in Spanish). Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- "Las elecciones del franquism". Diario Sur (in Spanish). Andalusia: Diario SUR Digital, S. L. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- "El voto femenino, el código civil y la dictadura franquista: el ningunero de la mujer en el ordenamiento jurídico español" (in Spanish). 2013-10-17. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- Ibáñez, Jesús María Palomares (2005). "Las elecciones de la Democracia Orgánica: el Ayuntamiento de Valladolid (1951-1971)". Investigaciones Históricas: Época Moderna y Contemporánea (25): 211–262. ISSN 0210-9425.

- Sevillano Calero, Francisco; Moreno Fonseret, Roque (1992). "La legitimación del franquismo: los plebiscitos de 1947 y 1966 en la provincia de Alicante". Anales de la Universidad de Alicante. Historia Contemporánea (8–9). doi:10.14198/AnContemp.1991-1992.8-9.08. ISSN 0212-5080.

- Davies, Catherine (1998-01-01). Spanish Women's Writing 1849-1996. A&C Black. ISBN 9780485910063.

- "Pioneras, desconocidas y silenciosas: Las primeras mujeres concejalas de Valladolid". El Norte de Castilla (in Spanish). 2018-12-03. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- Referendum 1966. Nueva Constitución. Madrid: Servicio Informativo Español (Ministerio de Información y Tursimo), 1966.

- "El régimen franquista, a referéndum". El Diario Vasco (in Spanish). 2006-12-14. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- Ruiz, Blanca Rodriguez; Rubio-Marín, Ruth (2012-06-07). The Struggle for Female Suffrage in Europe: Voting to Become Citizens. BRILL. ISBN 9789004224254.

- Jones, Anny Brooksbank (1997). Women in Contemporary Spain. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719047572.

- "El voto femenino en España". Historia (in Spanish). 2017-06-14. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p1824 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- País, Ediciones El (1978-10-26). "Los españoles entre 18 y 21 años no podrán votar en el referéndum". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- "Los españoles votaron en referéndum cuatro veces en los últimos 38 años". abc (in Spanish). 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- Zubiaur, Leire Imaz (2008). "La superación de la incapacidad de gestionar el propio patrimonio por parte de la mujer casada". Mujeres y Derecho, Pasado y Presente: I Congreso multidisciplinar de Centro-Sección de Bizkaia de la Facultad de Derecho. Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea. pp. 69–82. ISBN 978-84-9860-157-2.

- "Real Decreto de 24 de julio de 1889, texto de la edición del Código Civil mandada publicar en cumplimiento de la Ley de 26 de mayo Último. TíTULO IV.Del matrimonio". Noticias Jurídicas. Retrieved 2019-04-08.