Voting rights in the United States

The issue of voting rights in the United States, specifically the enfranchisement and disenfranchisement of different groups, has been contested throughout United States history.

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||

.svg.png.webp) | ||||||||

| Balloting | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Electoral systems | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Voting strategies | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Voting patterns and effects | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Electoral fraud | ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

Eligibility to vote in the United States is established both through the United States Constitution and by state law. Several constitutional amendments (the Fifteenth, Nineteenth, and Twenty-sixth specifically) require that voting rights of U.S. citizens cannot be abridged on account of race, color, previous condition of servitude, sex, or age (18 and older); the constitution as originally written did not establish any such rights during 1787–1870, except that if a state permitted a person to vote for the "most numerous branch" of its state legislature, it was required to permit that person to vote in elections for members of the United States House of Representatives.[1] In the absence of a specific federal law or constitutional provision, each state is given considerable discretion to establish qualifications for suffrage and candidacy within its own respective jurisdiction; in addition, states and lower level jurisdictions establish election systems, such as at-large or single member district elections for county councils or school boards. Beyond qualifications for suffrage, rules and regulations concerning voting (such as the poll tax) have been contested since the advent of Jim Crow laws and related provisions that indirectly disenfranchised racial minorities.

A historic turning point arrived when the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren ruled in 1964 that both houses of all state legislatures had to be based on election districts that were relatively equal in population size, under the "one man, one vote" principle.[2][3][4] The Warren Court's decisions on two previous landmark cases—Baker v. Carr (1962) and Wesberry v. Sanders (1964)—also played a fundamental role in establishing the nationwide "one man, one vote" electoral system.[5][6] Since the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Twenty-fourth Amendment, and related laws, voting rights have been legally considered an issue related to election systems. In 1972, the Burger Court ruled that state legislatures had to redistrict every ten years based on census results; at that point, many had not redistricted for decades, often leading to a rural bias.

In other cases, particularly for county or municipal elections, at-large voting has been repeatedly challenged when found to dilute the voting power of significant minorities in violation of the Voting Rights Act. In the early 20th century, numerous cities established small commission forms of government in the belief that "better government" could result from the suppression of ward politics. Commissioners were elected by the majority of voters, excluding candidates who could not afford large campaigns or who appealed to a minority. Generally the solution to such violations has been to adopt single-member districts (SMDs), but alternative election systems, such as limited voting or cumulative voting, have also been used since the late 20th century to correct for dilution of voting power and enable minorities to elect candidates of their choice.

The District of Columbia and five major territories of the United States have one non-voting member each (in the U.S. House of Representatives) and no representation in the U.S. Senate. People in the U.S. territories cannot vote for president of the United States.[7] People in the District of Columbia can vote for the president because of the Twenty-third Amendment.

Background

The right to vote is the foundation of any democracy. Chief Justice Earl Warren, for example, wrote in Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 555 (1964): "The right to vote freely for the candidate of one’s choice is of the essence of a democratic society, and any restrictions on that right strike at the heart of representative government. [...] Undoubtedly, the right of suffrage is a fundamental matter in a free and democratic society. Especially since the right to exercise the franchise in a free and unimpaired manner is preservative of other basic civil and political rights, any alleged infringement of the right of citizens to vote must be carefully and meticulously scrutinized." Justice Hugo Black shared the same sentiment by stating in Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1, 17 (1964): "No right is more precious in a free country than that of having a voice in the election of those who make the laws under which, as good citizens, we must live. Other rights, even the most basic, are illusory if the right to vote is undermined."

In the 17th-century Thirteen Colonies, suffrage was often restricted by property qualifications or with a religious test. In 1660, Plymouth Colony restricted suffrage with a specified property qualification, and in 1671, Plymouth Colony restricted suffrage further to only freemen "orthodox in the fundamentals of religion". Connecticut in mid-century also restricted suffrage with a specified property qualification and a religious test, and in Pennsylvania, the Province of Carolina, and the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations voting rights were restricted to Christians only. Under the Duke's Laws in colonial New York, suffrage did not require a religious test but was restricted to landholders. In Virginia, all white freemen were allowed to vote until suffrage was restricted temporarily to householders from 1655 to 1656, to freeholders from 1670 to 1676, and following the death of Nathaniel Bacon in 1676, to freeholders permanently. Quakers were not permitted to vote in Plymouth Colony or in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and along with Baptists, were not permitted to vote in several other colonies as well, and Catholics were disenfranchised following the Glorious Revolution (1688–1689) in Maryland, New York, Rhode Island, Carolina, and Virginia.[8]

In the 18th-century Thirteen Colonies, suffrage was restricted to white males with the following property qualifications:[9]

- Connecticut: an estate worth 40 shillings annually or £40 of personal property

- Delaware: fifty acres of land (twelve under cultivation) or £40 of personal property

- Georgia: fifty acres of land

- Maryland: fifty acres of land and £40 personal property

- Massachusetts Bay: an estate worth 40 shillings annually or £40 of personal property

- New Hampshire: £50 of personal property

- New Jersey: one-hundred acres of land, or real estate or personal property £50

- New York: £40 of personal property or ownership of land

- North Carolina: fifty acres of land

- Pennsylvania: fifty acres of land or £50 of personal property

- Rhode Island and Providence Plantations: personal property worth £40 or yielding 50 shillings annually

- South Carolina: one-hundred acres of land on which taxes were paid; or a town house or lot worth £60 on which taxes were paid; or payment of 10 shillings in taxes

- Virginia: fifty acres of vacant land, twenty-fives acres of cultivated land, and a house twelve feet by twelve feet; or a town lot and a house twelve feet by twelve

The United States Constitution did not originally define who was eligible to vote, allowing each state to determine who was eligible. In the early history of the U.S., some states allowed only white male adult property owners to vote, while others either did not specify race, or specifically protected the rights of men of any race to vote.[10][11][12][13] Freed slaves could vote in four states.[14] Women were largely prohibited from voting, as were men without property. Women could vote in New Jersey until 1807 (provided they could meet the property requirement) and in some local jurisdictions in other northern states. Non-white Americans could also vote in these jurisdictions, provided they could meet the property requirement.

Beginning around 1790, individual states began to reassess property ownership as a qualification for enfranchisement in favor of gender and race, with most states disenfranchising women and non-white men.[15] By 1856, white men were allowed to vote in all states regardless of property ownership, although requirements for paying tax remained in five states.[16][17] On the other hand, several states, including Pennsylvania and New Jersey stripped the free black males of the right to vote in the same period.

Four of the fifteen post-Civil War constitutional amendments were ratified to extend voting rights to different groups of citizens. These extensions state that voting rights cannot be denied or abridged based on the following:

- "Race, color, or previous condition of servitude" (Fifteenth Amendment, 1870)

- "On account of sex" (Nineteenth Amendment, 1920)

- "By reason of failure to pay any poll tax or other tax" for federal elections (Twenty-fourth Amendment, 1964)[Note 1]

- "Who are eighteen years of age or older, to vote, shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of age" (Twenty-sixth Amendment, 1971)

Following the Reconstruction Era until the culmination of the Civil Rights Movement, Jim Crow laws such as literacy tests, poll taxes, and religious tests were some of the state and local laws used in various parts of the United States to deny immigrants (including legal ones and newly naturalized citizens), non-white citizens, Native Americans, and any other locally "undesirable" groups from exercising voting rights granted under the Constitution.[18] Because of such state and local discriminatory practices, over time, the federal role in elections has increased, through amendments to the Constitution and enacted legislation. These reforms in the 19th and 20th centuries extended the franchise to non-whites, those who do not own property, women, and those 18–21 years old.

Since the "right to vote" is not explicitly stated in the U.S. Constitution except in the above referenced amendments, and only in reference to the fact that the franchise cannot be denied or abridged based solely on the aforementioned qualifications, the "right to vote" is perhaps better understood, in layman's terms, as only prohibiting certain forms of legal discrimination in establishing qualifications for suffrage. States may deny the "right to vote" for other reasons. For example, many states require eligible citizens to register to vote a set number of days prior to the election in order to vote. More controversial restrictions include those laws that prohibit convicted felons from voting, even those who have served their sentences. Another example, seen in Bush v. Gore, are disputes as to what rules should apply in counting or recounting ballots.[19]

A state may choose to fill an office by means other than an election. For example, upon death or resignation of a legislator, the state may allow the affiliated political party to choose a replacement to hold office until the next scheduled election. Such an appointment is often affirmed by the governor.[20]

The Constitution, in Article VI, clause (paragraph) 3, does state that "no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States".

Milestones of national franchise changes

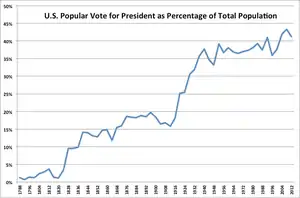

- 1789: The Constitution grants the states the power to set voting requirements. Generally, states limited this right to property-owning or tax-paying white males (about 6% of the population).[11]

- 1790: The Naturalization Act of 1790 allows white men born outside of the United States to become citizens with the right to vote.

- 1792–1838: Free black males lose the right to vote in several Northern states including in Pennsylvania and in New Jersey.

- 1792–1856: Abolition of property qualifications for white men, from 1792 (New Hampshire) to 1856 (North Carolina) during the periods of Jeffersonian and Jacksonian democracy. However, tax-paying qualifications remained in five states in 1860—Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Delaware and North Carolina. They survived in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island until the 20th century.[16]

- In the 1820 election, there were 108,359 ballots cast. Most older states with property restrictions dropped them by the mid-1820s, except for Rhode Island, Virginia and North Carolina. No new states had property qualifications although three had adopted tax-paying qualifications – Ohio, Louisiana, and Mississippi, of which only in Louisiana were these significant and long lasting.[21]

- The 1828 presidential election was the first in which non-property-holding white males could vote in the vast majority of states. By the end of the 1820s, attitudes and state laws had shifted in favor of universal white male suffrage.[22]

- Voter turnout soared during the 1830s, reaching about 80% of adult white male population in the 1840 presidential election.[23] 2,412,694 ballots were cast, an increase that far outstripped natural population growth, making poor voters a huge part of the electorate. The process was peaceful and widely supported, except in the state of Rhode Island where the Dorr Rebellion of the 1840s demonstrated that the demand for equal suffrage was broad and strong, although the subsequent reform included a significant property requirement for anyone resident but born outside of the United States.

- The last state to abolish property qualification was North Carolina in 1856. However, tax-paying qualifications remained in five states in 1860 – Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Delaware and North Carolina. They survived in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island until the 20th century.[24] In addition, many poor whites were later disenfranchised.[25][26]

- 1868: Citizenship is guaranteed to all persons born or naturalized in the United States by the Fourteenth Amendment, setting the stage for future expansions to voting rights.

- 1869–1920: Some states allow women to vote. Wyoming was the first state to give women voting rights in 1869.

- 1870: Non-white men and freed male slaves are guaranteed the right to vote by the Fifteenth Amendment. Disenfranchisement after the Reconstruction Era began soon after. Southern states suppressed the voting rights of black and poor white voters through Jim Crow Laws. During this period, the Supreme Court generally upheld state efforts to discriminate against racial minorities; only later in the 20th century were these laws ruled unconstitutional. Black males in the Northern states could vote, but the majority of African Americans lived in the South.[27][28]

- 1887: Citizenship is granted to Native Americans who are willing to disassociate themselves from their tribe by the Dawes Act, making the men technically eligible to vote.

- 1913: Direct election of Senators, established by the Seventeenth Amendment, gave voters rather than state legislatures the right to elect senators.[29]

- 1920: Women are guaranteed the right to vote in all US States by the Nineteenth Amendment. In practice, the same restrictions that hindered the ability of poor or non-white men to vote now also applied to poor or non-white women.

- 1924: All Native Americans are granted citizenship and the right to vote, regardless of tribal affiliation. By this point, approximately two thirds of Native Americans were already citizens.[30][31] Notwithstanding, some western states continued to bar Native Americans from voting until 1948.[32]

- 1943: Chinese immigrants given the right to citizenship and the right to vote by the Magnuson Act.

- 1948: Arizona and New Mexico became one of the last states to extend full voting rights to Native Americans, which had been opposed by some western states in contravention of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.[32][33]

- 1954-1955: Maine extends full voting rights to Native Americans who live on reservations.[34][35] Activist, Lucy Nicolar Poolaw (Penobscot), is the first to cast her vote under the new law.[35]

- 1961: Residents of Washington, D.C. are granted the right to vote in U.S. Presidential Elections by the Twenty-third Amendment.

- 1962-1964: A historic turning point arrived after the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren made a series of landmark decisions which helped establish the nationwide "one man, one vote" electoral system in the United States.

- In March 1962, the Warren Court ruled in Baker v. Carr (1962) that redistricting qualifies as a justiciable question, thus enabling federal courts to hear redistricting cases.[5]

- In February 1964, the Warren Court ruled in Wesberry v. Sanders (1964) that districts in the United States House of Representatives must be approximately equal in population.[6]

- In June 1964, the Warren Court ruled in Reynolds v. Sims (1964) that both houses of the electoral districts of state legislative chambers must be roughly equal in population.[2][3][4]

- 1964: Poll Tax payment prohibited from being used as a condition for voting in federal elections by the Twenty-fourth Amendment.

- 1965: Protection of voter registration and voting for racial minorities, later applied to language minorities, is established by the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This has also been applied to correcting discriminatory election systems and districting.[36]

- 1966: Tax payment and wealth requirements for voting in state elections are prohibited by the Supreme Court in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections.

- 1971: Adults aged 18 through 21 are granted the right to vote by the Twenty-sixth Amendment. This was enacted in response to Vietnam War protests, which argued that soldiers who were old enough to fight for their country should be granted the right to vote.[29][37]

- 1986: United States Military and Uniformed Services, Merchant Marine, other citizens overseas, living on bases in the United States, abroad, or aboard ship are granted the right to vote by the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act.[38]

Native American people

From 1778 to 1871, the government tried to resolve its relationship with the various native tribes by negotiating treaties. These treaties formed agreements between two sovereign nations, stating that Native American people were citizens of their tribe, living within the boundaries of the United States. The treaties were negotiated by the executive branch and ratified by the U.S. Senate. It said that native tribes would give up their rights to hunt and live on huge parcels of land that they had inhabited in exchange for trade goods, yearly cash annuity payments, and assurances that no further demands would be made on them. Most often, part of the land would be "reserved" exclusively for the tribe's use.[39]

Throughout the 1800s, many native tribes gradually lost claim to the lands they had inhabited for centuries through the federal government's Indian Removal policy to relocate tribes from the Southeast and Northwest to west of the Mississippi River. European-American settlers continued to encroach on western lands. Only in 1879, in the Standing Bear trial, were American Indians recognized as persons in the eyes of the United States government. Judge Elmer Scipio Dundy of Nebraska declared that Indians were people within the meaning of the laws, and they had the rights associated with a writ of habeas corpus. However, Judge Dundy left unsettled the question as to whether Native Americans were guaranteed US citizenship.[40]

Although Native Americans were born within the national boundaries of the United States, those on reservations were considered citizens of their own tribes, rather than of the United States. They were denied the right to vote because they were not considered citizens by law and were thus ineligible. Many Native Americans were told they would become citizens if they gave up their tribal affiliations in 1887 under the Dawes Act, which allocated communal lands to individual households and was intended to aid in the assimilation of Native Americans into majority culture. This still did not guarantee their right to vote. In 1924, the remaining Native Americans, estimated at about one-third, became United States citizens through the Indian Citizenship Act. Many western states, however, continued to restrict Native American ability to vote through property requirements, economic pressures, hiding the polls, and condoning of physical violence against those who voted.[41] Since the late 20th century, they have been protected under provisions of the Voting Rights Act as a racial minority, and in some areas, language minority, gaining election materials in their native languages.

Alaska Natives

The Alaskan Territory did not consider Alaska Natives to be citizens of the United States and so they could not vote.[42][43] An exception to this rule was that indigenous women were considered citizens if they were married to white men.[43] In 1915, the Territorial Legislature passed a law that allowed Alaska Natives the right to vote if they gave their "tribal customs and traditions."[42] William Paul (Tlingit) fought for the right of Alaska Natives to vote during the 1920s.[44] Others, like Tillie Paul (Tlingit) and Charlie Jones (Tlingit), were arrested for voting because they were still not considered citizens.[45] Later, Paul would win a court case that set the precedent that Alaska Natives were legally allowed to vote.[46][47] In 1925, a literacy test was passed in Alaska to suppress the votes of Alaska Natives.[48] After passage of the Alaska Equal Rights Act of 1945, Alaska Natives gained more rights, but there was still voter discrimination.[49][50] When Alaska became a state, the new constitution provided Alaskans with a more lenient literacy test.[51] In 1970, the state legislature ratified a constitutional amendment against state voter literacy tests.[51] The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), modified in 1975, provided additional help for Alaska Natives who do not speak English, which affects around 14 census areas.[52][53][54] Many villages with large Alaska Native populations continue to face difficulties voting.[55]

Religious test

In several British North American colonies, before and after the 1776 Declaration of Independence, Jews, Quakers and/or Catholics were excluded from the franchise and/or from running for elections.[56]

The Delaware Constitution of 1776 stated that "Every person who shall be chosen a member of either house, or appointed to any office or place of trust, before taking his seat, or entering upon the execution of his office, shall ... also make and subscribe the following declaration, to wit: I, A B. do profess faith in God the Father, and in Jesus Christ His only Son, and in the Holy Ghost, one God, blessed for evermore; and I do acknowledge the holy scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by divine inspiration.".[57] This was repealed by Article I, Section II. of the 1792 Constitution: "No religious test shall be required as a qualification to any office, or public trust, under this State".[58] The 1778 Constitution of the State of South Carolina stated, "No person shall be eligible to sit in the house of representatives unless he be of the Protestant religion",[59] the 1777 Constitution of the State of Georgia (art. VI) that "The representatives shall be chosen out of the residents in each county ... and they shall be of the Protestant religion".[60]

With the growth in the number of Baptists in Virginia before the Revolution, who challenged the established Anglican Church, the issues of religious freedom became important to rising leaders such as James Madison. As a young lawyer, he defended Baptist preachers who were not licensed by (and were opposed by) the established state Anglican Church. He carried developing ideas about religious freedom to be incorporated into the constitutional convention of the United States.

In 1787, Article One of the United States Constitution stated that "the Electors in each State shall have the Qualifications requisite for Electors of the most numerous Branch of the State Legislature". More significantly, Article Six disavowed the religious test requirements of several states, saying: "[N]o religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States."

But, in Maryland, Jewish Americans were excluded from State office until the law requiring candidates to affirm a belief in an afterlife[61] was repealed in 1828.

African Americans and poor whites

At the time of ratification of the Constitution in the late 18th century, most states had property qualifications which restricted the franchise; the exact amount varied by state, but by some estimates, more than half of white men were disenfranchised.[62] Several states granted suffrage to free men of color after the Revolution, including North Carolina. This fact was noted by Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis' dissent in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), as he emphasized that blacks had been considered citizens at the time the Constitution was ratified:

Of this there can be no doubt. At the time of the ratification of the Articles of Confederation, all free native-born inhabitants of the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and North Carolina, though descended from African slaves, were not only citizens of those States, but such of them as had the other necessary qualifications possessed the franchise of electors, on equal terms with other citizens.[63]

- In the 1820s, New York State enlarged its franchise to white men by dropping the property qualification, but maintained it for free blacks.[64]

- The Supreme Court of North Carolina had upheld the ability of free African Americans to vote in that state. In 1835, because of fears of the role of free blacks after Nat Turner's Slave Rebellion of 1831, they were disenfranchised by decision of the North Carolina Constitutional Convention. At the same time, convention delegates relaxed religious and property qualifications for whites, thus expanding the franchise for them.[65]

- Alabama entered the union in 1819 with universal white suffrage provided in its constitution.

While opposed to slavery, in a speech in Charleston, Illinois, in 1858, Abraham Lincoln stated, "I am not, nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office."[66] When the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868 after the Civil War, it granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction. In 1869, the Fifteenth Amendment prohibited the government from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude". The major effect of these amendments was to enfranchise African American men, the overwhelming majority of whom were freedmen in the South.[67]

After the war, some Southern states passed "Black Codes", state laws to restrict the new freedoms of African Americans. They attempted to control their movement, assembly, working conditions and other civil rights. Some states also prohibited them from voting.[67]

The Fifteenth Amendment, one of three ratified after the American Civil War to grant freedmen full rights of citizenship, prevented any state from denying the right to vote to any citizen based on race. This was primarily related to protecting the franchise of freedmen, but it also applied to non-white minorities, such as Mexican Americans in Texas. The state governments under Reconstruction adopted new state constitutions or amendments designed to protect the ability of freedmen to vote. The white resistance to black suffrage after the war regularly erupted into violence as white groups tried to protect their power. Particularly in the South, in the aftermath of the Civil War whites made efforts to suppress freedmen's voting. In the 1860s, secret vigilante groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) used violence and intimidation to keep freedmen in a controlled role and reestablish white supremacy. But, black freedmen registered and voted in high numbers, and many were elected to local offices through the 1880s.

In the mid-1870s, the insurgencies continued with a rise in more powerful white paramilitary groups, such as the White League, originating in Louisiana in 1874 after a disputed gubernatorial election; and the Red Shirts, originating in Mississippi in 1875 and developing numerous chapters in North and South Carolina; as well as other "White Line" rifle clubs. They operated openly, were more organized than the KKK, and directed their efforts at political goals: to disrupt Republican organizing, turn Republicans out of office, and intimidate or kill blacks to suppress black voting. They worked as "the military arm of the Democratic Party".[68] For instance, estimates were that 150 blacks were killed in North Carolina before the 1876 elections. Economic tactics such as eviction from rental housing or termination of employment were also used to suppress the black vote. White Democrats regained power in state legislatures across the South by the late 1870s, and the federal government withdrew its troops as a result of a national compromise related to the presidency, officially ending Reconstruction.

African Americans were a majority in three Southern states following the Civil War, and represented over 40% of the population in four other states and many whites feared and resented the political power exercised by freedmen.[69] After ousting the Republicans, whites worked to restore white supremacy.

Although elections were often surrounded by violence, blacks continued to vote and gained many local offices in the late 19th century. In the late 19th century, a Populist-Republican coalition in several states gained governorships and some congressional seats in 1894. To prevent such a coalition from forming again and reduce election violence, the Democratic Party, dominant in all southern state legislatures, took action to disfranchise most blacks and many poor whites outright.

From 1890 to 1908, ten of the eleven former Confederate states completed political suppression and exclusion of these groups by ratifying new constitutions or amendments which incorporated provisions to make voter registration more difficult. These included such requirements as payment of poll taxes, complicated record keeping, complicated timing of registration and length of residency in relation to elections, with related record-keeping requirements; felony disenfranchisement focusing on crimes thought to be committed by African Americans,[70] and a literacy test or comprehension test.

This was defended openly, on the floor of the Senate, by South Carolina Senator and former Governor Benjamin Tillman:

In my State there were 135,000 negro voters, or negroes of voting age, and some 90,000 or 95,000 white voters. ... Now, I want to ask you, with a free vote and a fair count, how are you going to beat 135,000 by 95,000? How are you going to do it? You had set us an impossible task.

We did not disfranchise the negroes until 1895. Then we had a constitutional convention convened which took the matter up calmly, deliberately, and avowedly with the purpose of disfranchising as many of them as we could under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. We adopted the educational qualification as the only means left to us, and the negro is as contented and as prosperous and as well protected in South Carolina to-day as in any State of the Union south of the Potomac. He is not meddling with politics, for he found that the more he meddled with them the worse off he got. As to his "rights"—I will not discuss them now. We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern white men, and we never will. ... I would to God the last one of them was in Africa and that none of them had ever been brought to our shores.[71]

Prospective voters had to prove the ability to read and write the English language to white voter registrars, who in practice applied subjective requirements. Blacks were often denied the right to vote on this basis. Even well-educated blacks were often told they had "failed" such a test, if in fact, it had been administered. On the other hand, illiterate whites were sometimes allowed to vote through a "grandfather clause," which waived literacy requirements if one's grandfather had been a qualified voter before 1866, or had served as a soldier, or was from a foreign country. As most blacks had grandfathers who were slaves before 1866 and could not have fulfilled any of those conditions, they could not use the grandfather clause exemption. Selective enforcement of the poll tax was frequently also used to disqualify black and poor white voters. As a result of these measures, at the turn of the century voter rolls dropped markedly across the South. Most blacks and many poor whites were excluded from the political system for decades. Unable to vote, they were also excluded from juries or running for any office.

In Alabama, for example, its 1901 constitution restricted the franchise for poor whites as well as blacks. It contained requirements for payment of cumulative poll taxes, completion of literacy tests, and increased residency at state, county and precinct levels, effectively disenfranchising tens of thousands of poor whites as well as most blacks. Historian J. Morgan Kousser found, "They disfranchised these whites as willingly as they deprived blacks of the vote."[72] By 1941, more whites than blacks in total had been disenfranchised.[73]

Legal challenges to disfranchisement

Although African Americans quickly began legal challenges to such provisions in the 19th century, it was years before any were successful before the U.S. Supreme Court. Booker T. Washington, better known for his public stance of trying to work within societal constraints of the period at Tuskegee University, secretly helped fund and arrange representation for numerous legal challenges to disfranchisement. He called upon wealthy Northern allies and philanthropists to raise funds for the cause.[74] The Supreme Court's upholding of Mississippi's new constitution, in Williams v. Mississippi (1898), encouraged other states to follow the Mississippi plan of disfranchisement. African Americans brought other legal challenges, as in Giles v. Harris (1903) and Giles v. Teasley (1904), but the Supreme Court upheld Alabama constitutional provisions. In 1915, Oklahoma was the last state to append a grandfather clause to its literacy requirement due to Supreme Court cases.

From early in the 20th century, the newly established National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) took the lead in organizing or supporting legal challenges to segregation and disfranchisement. Gradually they planned the strategy of which cases to take forward. In Guinn v. United States (1915), the first case in which the NAACP filed a brief, the Supreme Court struck down the grandfather clause in Oklahoma and Maryland. Other states in which it was used had to retract their legislation as well. The challenge was successful.

But, nearly as rapidly as the Supreme Court determined a specific provision was unconstitutional, state legislatures developed new statutes to continue disenfranchisement. For instance, in Smith v. Allwright (1944), the Supreme Court struck down the use of state-sanctioned all-white primaries by the Democratic Party in the South. States developed new restrictions on black voting; Alabama passed a law giving county registrars more authority as to which questions they asked applicants in comprehension or literacy tests. The NAACP continued with steady progress in legal challenges to disenfranchisement and segregation.

In 1957, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1957 to implement the Fifteenth Amendment. It established the United States Civil Rights Commission; among its duties is to investigate voter discrimination.

As late as 1962, programs such as Operation Eagle Eye in Arizona attempted to stymie minority voting through literacy tests. The Twenty-fourth Amendment was ratified in 1964 to prohibit poll taxes as a condition of voter registration and voting in federal elections. Many states continued to use them in state elections as a means of reducing the number of voters.

The American Civil Rights Movement, through such events as the Selma to Montgomery marches and Freedom Summer in Mississippi, gained passage by the United States Congress of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which authorized federal oversight of voter registration and election practices and other enforcement of voting rights. Congress passed the legislation because it found "case by case litigation was inadequate to combat widespread and persistent discrimination in voting". Activism by African Americans helped secure an expanded and protected franchise that has benefited all Americans, including racial and language minorities.

The bill provided for federal oversight, if necessary, to ensure just voter registration and election procedures. The rate of African-American registration and voting in Southern states climbed dramatically and quickly, but it has taken years of federal oversight to work out the processes and overcome local resistance. In addition, it was not until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 6–3 in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections (1966) that all state poll taxes (for state elections) were officially declared unconstitutional as violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This removed a burden on the poor.[75][76]

Legal challenges have continued under the Voting Rights Act, primarily in areas of redistricting and election systems, for instance, challenging at-large election systems that effectively reduce the ability of minority groups to elect candidates of their choice. Such challenges have particularly occurred at the county and municipal level, including for school boards, where exclusion of minority groups and candidates at such levels has been persistent in some areas of the country. This reduces the ability of women and minorities to participate in the political system and gain entry-level experience.

Asian Americans

Voting rights for Asian Americans have been continuously battled for in the United States since the initial significant wave of Asian immigration to the country in the mid-nineteenth century.[77] The escalation of voting rights issues for Asian immigrants had started with the citizenship status of Chinese Americans from 1882 with the Chinese Exclusion Act that was inspired by and built upon the Naturalization Act of 1870.[78] The latter act helped the judicial system decide a person's ethnicity, and if the person was white, they could proceed with the immigration process.[78] While the Chinese Exclusion Act specifically targeted and banned the influx of Asian immigrants looking for work on the west coast due to the country that they were from and their ethnicity.[79] Without the ability to become an American citizen, Asian immigrants were prohibited from voting or even immigrating to the United States during this time.

Things started to improve when the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in the mid-twentieth century, and Chinese immigrants were once again able to seek citizenship and voting rights.[80] In spite of these setbacks, it was not a complete ban for Asian Americans; simultaneously, a minority of Asian Americans were politically active during this era of the 1870 Naturalization Act and Chinese exclusion.[81] However, the Asian American community gained significant advancements in their voting rights later, with the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952. With this Act, the Asian American community was able to seek citizenship that was not on the basis of race but on a quota system that was dependent upon their country of emigration.[82] Shortly after the McCarran-Walter Act, the Voting Rights Act was signed by President Johnson in 1965. It thus came a new era of civil liberties for Asian Americans who were in the voting minority.[83][84]

Women

A parallel, yet separate, movement was that for women's suffrage. Leaders of the suffrage movement included Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Alice Paul. In some ways this, too, could be said to have grown out of the American Civil War, as women had been strong leaders of the abolition movement. Middle- and upper-class women generally became more politically active in the northern tier during and after the war.

In 1848, the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, was held in Seneca Falls, New York. Of the 300 present, 68 women and 32 men signed the Declaration of Sentiments which defined the women's rights movement. The first National Women's Rights Convention took place in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts, attracting more than 1,000 participants. This national convention was held yearly through 1860.

When Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton formed the National Women Suffrage Association, their goal was to help women gain voting rights through reliance on the Constitution. Also, in 1869 Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). However, AWSA focused on gaining voting rights for women through the amendment process. Although these two organization were fighting for the same cause, it was not until 1890 that they merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). After the merger of the two organizations, the (NAWSA) waged a state-by-state campaign to obtain voting rights for women.

Wyoming was the first state in which women were able to vote, although it was a condition of the transition to statehood. Utah was the second territory to allow women to vote, but the federal Edmunds–Tucker Act of 1887 repealed woman's suffrage in Utah. Colorado was the first established state to allow women to vote on the same basis as men. Some other states also extended the franchise to women before the Constitution was amended to this purpose.

During the 1910s Alice Paul, assisted by Lucy Burns and many others, organized such events and organizations as the 1913 Women's Suffrage Parade, the National Woman's Party, and the Silent Sentinels. At the culmination of the suffragists' requests and protests, ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment gave women the right to vote in time to participate in the Presidential election of 1920.

Another political movement that was largely driven by women in the same era was the anti-alcohol Temperance movement, which led to the Eighteenth Amendment and Prohibition.[85]

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., was created from a portion of the states of Maryland and Virginia in 1801. The Virginia portion was retroceded (returned) to Virginia upon request of the residents, by an Act of Congress in 1846 to protect slavery, and restore state and federal voting rights in that portion of Virginia. When Maryland delegated a portion of its land to Congress so it could be used as the Nation's capital, Congress did not continue Maryland Voting Laws. It canceled all state and federal elections starting with 1802. Local elections limped on in some neighborhoods, until 1871, when local elections were also forbidden by the U.S. Congress. The U.S. Congress is the National Legislature. Under Article I, Section 8, Clause 17, Congress has the sole authority to exercise "Exclusive Legislature in all cases whatsoever" over the nation's capital and over federal military bases. Active disfranchisement is typically a States Rights Legislative issue, where the removal of voting rights is permitted. At the national level, the federal government typically ignored voting rights issues, or affirmed that they were extended.

Congress, when exercising "exclusive legislation" over U.S. Military Bases in the United States, and Washington, D.C., viewed its power as strong enough to remove all voting rights. All state and federal elections were canceled by Congress in D.C. and all of Maryland's voting Rights laws no longer applied to D.C. when Maryland gave up that land. Congress did not pass laws to establish local voting processes in the District of Columbia. This omission of law strategy to disfranchise is contained in the Congressional debates in Annals of Congress in 1800 and 1801.

In 1986, the US Congress voted to restore voting rights on U.S. Military bases for all state and federal elections.

D.C. citizens were granted the right to vote in Presidential elections in 1961 after ratification of the Twenty-third Amendment. The citizens and territory converted in 1801 were represented by John Chew Thomas from Maryland's 2nd, and William Craik from Maryland's 3rd Congressional Districts, which were redrawn and removed from the city.

No full Congressional elections have been held since in D.C., a gap continuing since 1801. Congress created a non-voting substitute for a U.S. Congressman, a Delegate, between 1871 and 1875, but then abolished that post as well. Congress permitted restoration of local elections and home rule for the District on December 24, 1973. In 1971, Congress still opposed restoring the position of a full U.S. Congressman for Washington, D.C. That year it re-established the position of non-voting Delegate to the U.S. Congress.[86]

Young adults

A third voting rights movement was won in the 1960s to lower the voting age from twenty-one to eighteen. Activists noted that most of the young men who were being drafted to fight in the Vietnam War were too young to have any voice in the selection of the leaders who were sending them to fight. Some states had already lowered the voting age: notably Georgia, Kentucky, and Hawaii, had already permitted voting by persons younger than twenty-one.

The Twenty-sixth Amendment, ratified in 1971, prohibits federal and state laws which set a minimum voting age higher than 18 years. As of 2008, no state has opted for an earlier age, although some state governments have discussed it.[87] California has, since the 1980s, allowed persons who are 17 to register to vote for an election where the election itself will occur on or after their 18th birthday, and several states including Indiana allow 17-year-olds to vote in a primary election provided they will be 18 by the general election.

Prisoners

Prisoner voting rights are defined by individual states, and the laws are different from state to state. Some states allow only individuals on probation to vote. Others allow individuals on parole and probation. As of 2012, only Florida, Kentucky and Virginia continue to impose a lifelong denial of the right to vote to all citizens with a felony record, absent a restoration of rights granted by the Governor or state legislature.[88] However, in Kentucky, a felon's rights can be restored after the completion of a restoration process to regain civil rights.[88][89]

In 2007, Florida legislature restored voting rights to convicted felons who had served their sentences. In March 2011, however, Governor Rick Scott reversed the 2007 reforms. He signed legislation that permanently disenfranchises citizens with past felony convictions. After a referendum in 2018, however, Florida residents voted to restore voting rights to roughly 1.4 million felons who have completed their sentences.[90]

In July 2005, Iowa Governor Tom Vilsack issued an executive order restoring the right to vote for all persons who have completed supervision.[88] On October 31, 2005, Iowa's Supreme Court upheld mass reenfranchisement of convicted felons. Nine other states disenfranchise felons for various lengths of time following the completion of their probation or parole.

Other than Maine and Vermont, all U.S. states prohibit felons from voting while they are in prison.[91] In Puerto Rico, felons in prison are allowed to vote in elections.

Practices in the United States are in contrast to some European nations that allow prisoners to vote, while other European countries have restrictions on voting while serving a prison sentence, but not after release.[92] Prisoners have been allowed to vote in Canada since 2002.[93]

The United States has a higher proportion of its population in prison than any other Western nation,[94] and more than Russia or China.[95] The dramatic rise in the rate of incarceration in the United States, a 500% increase from the 1970s to the 1990s,[96] has vastly increased the number of people disenfranchised because of the felon provisions.

According to the Sentencing Project, as of 2010 an estimated 5.9 million Americans are denied the right to vote because of a felony conviction, a number equivalent to 2.5% of the U.S. voting-age population and a sharp increase from the 1.2 million people affected by felony disenfranchisement in 1976.[96] Given the prison populations, the effects have been most disadvantageous for minority and poor communities.[97]

Durational residency

The Supreme Court of the United States struck down one-year residency requirements to vote in Dunn v. Blumstein 405 U.S. 330 (1972).[98] The Court ruled that limits on voter registration of up to 30 to 50 days prior to an election were permissible for logistical reasons, but that residency requirements in excess of that violated the equal protection clause, as granted under the Fourteenth Amendment, according to strict scrutiny.

Disability

In some states, people who are deemed mentally incompetent are not allowed to vote.[99] Voting rights specialist Michelle Bishop has said, "We are the last demographic within the U.S. where you can take away our right to vote because of our identity."[100]

In the conservatorship process, people can lose their right to vote.[101] In California, SB 589 was passed in 2015, which created the presumption that those under conservatorship can vote.[102]

Homelessness

In the 1980s homelessness was recognized as an increasing national problem. By the early 21st century, there have been numerous court cases to help protect the voting rights of persons without a fixed address. Low income and homeless citizens face some obstacles in registering to vote. These obstacles include establishing residency, providing a mailing address, and showing proof of identification. A residency requirement varies from state to state. States cannot require citizens to show residency of more than 30 days before Election Day. The states of Idaho, Maine, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Wyoming allow voters to register on Election Day. North Dakota does not require voters to register.[103]

All potential voters face new requirements since 2002, when President Bush signed the Help America Vote Act (HAVA).[104][105] It requires voters to provide their driver's license numbers, or the last four digits of their Social Security Number on their voter registration form. This has been enforced.

Special interest elections

Several locales retained restrictions for specialized local elections, such as for school boards, special districts, or bond issues. Property restrictions, duration of residency restrictions, and, for school boards, restrictions of the franchise to voters with children, remained in force. In a series of rulings from 1969 to 1973, the Court ruled that the franchise could be restricted in some cases to those "primarily interested" or "primarily affected" by the outcome of a specialized election, but not in the case of school boards or bond issues, which affected taxation to be paid by all residents.[20] In Ball v. James 451 U.S. 335 (1981), the Court further upheld a system of plural voting, by which votes for the board of directors of a water reclamation district were allocated on the basis of a person's proportion of land owned in the district.[20]

The Court has overseen operation of political party primaries to ensure open voting. While states were permitted to require voters to register for a political party 30 days before an election, or to require them to vote in only one party primary, the state could not prevent a voter from voting in a party primary if the voter has voted in another party's primary in the last 23 months.[20] The Court also ruled that a state may not mandate a "closed primary" system and bar independents from voting in a party's primary against the wishes of the party. (Tashijan v. Republican Party of Connecticut 479 U.S. 208 (1986))[106]

The Office of Hawaiian Affairs of the state of Hawaii, created in 1978, limited voting eligibility and candidate eligibility to native Hawaiians on whose behalf it manages 1,800,000 acres (7,300 km2) of ceded land. The Supreme Court of the United States struck down the franchise restriction under the Fifteenth Amendment in Rice v. Cayetano 528 U.S. 495 (2000), following by eliminating the candidate restriction in Arakaki v. State of Hawai'i a few months later.

Current status by region

District of Columbia

Citizens of the nation's capital, Washington, D.C., have not been apportioned a representative or US senator in Congress. This is because D.C. is a federal district and not a state and, under the Constitution, only states are apportioned congresspersons.

District of Columbia citizens had voting rights removed in 1801 by Congress, when Maryland delegated that portion of its land to Congress. Congress incrementally removed effective local control or home rule by 1871. It restored some home rule in 1971, but maintained the authority to override any local laws. Washington, D.C., does not have full representation in the U.S. House or Senate. The Twenty-third Amendment, restoring U.S. Presidential Election after a 164-year-gap, is the only known limit to Congressional "exclusive legislature" from Article I-8-17, forcing Congress to enforce for the first time Amendments 14, 15, 19, 24, and 26. It gave the District of Columbia three electors and hence the right to vote for President, but not full U.S. Congresspersons nor U.S. Senators. In 1978, another amendment was proposed which would have restored to the District a full seat, but it failed to receive ratification by a sufficient number of states within the seven years required.

As of 2013, a bill is pending in Congress that would treat the District of Columbia as "a congressional district for purposes of representation in the House of Representatives", and permit United States citizens residing in the capital to vote for a member to represent them in the House of Representatives. The District of Columbia House Voting Rights Act, S. 160, 111th Cong. was passed by the U.S. Senate on February 26, 2009, by a vote of 61–37.[107]

On April 1, 1993, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights of the Organization of American States received a petition from Timothy Cooper on behalf of the Statehood Solidarity Committee (the "Petitioners") against the government of the United States (the "State" or "United States"). The petition indicated that it was presented on behalf of the members of the Statehood Solidarity Committee and all other U.S. citizens resident in the District of Columbia. The petition alleged that the United States was responsible for violations of Articles II (right to equality before law) and XX (right to vote and to participate in government) of the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man in connection with the inability of citizens of the District of Columbia to vote for and elect a representative to the U.S. Congress. On December 29, 2003, The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights having examined the information and arguments provided by the parties on the question of admissibility. Without prejudging the merits of the matter, the Commission decided to admit the present petition in respect of Articles II and XX of the American Declaration. In addition, the Commission concluded that the United States violates the Petitioners' rights under Articles II and XX of the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man by denying District of Columbia citizens an effective opportunity to participate in their federal legislature.[108]

Overseas and nonresident citizens

U.S. citizens residing overseas who would otherwise have the right to vote are guaranteed the right to vote in federal elections by the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA) of 1986.[38] As a practical matter, individual states implement UOCAVA.

A citizen who has never resided in the United States can vote if a parent is eligible to vote in certain states.[109] In some of these states the citizen can vote in local, state, and federal elections, in others in federal elections only.

Voting rights of U.S. citizens who have never established residence in the U.S.vary by state and may be impacted by the residence history of their parents.[110]

U.S. territories

U.S. citizens and non-citizen nationals who reside in American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, or the United States Virgin Islands are not allowed to vote in U.S. national and presidential elections, as these U.S. territories belong to the United States but do not have presidential electors. The U.S. Constitution requires a voter to be resident in one of the 50 states or in the District of Columbia to vote in federal elections. To say that the Constitution does not require extension of federal voting rights to U.S. territories residents does not, however, exclude the possibility that the Constitution may permit their enfranchisement under another source of law. Statehood or a constitutional amendment would allow people in the U.S. territories to vote in federal elections.[111]

Like the District of Columbia, territories of the United States do not have U.S. senators representing them in the senate, and they each have one member of the House of Representatives who is not allowed to vote.[7]

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico is an insular area—a United States territory that is neither a part of one of the fifty states nor a part of the District of Columbia, the nation's federal district. Insular areas, such as Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands and Guam, are not allowed to choose electors in U.S. presidential elections or elect voting members to the U.S. Congress. This grows out of Article I and Article II of the United States Constitution, which specifically mandate that electors are to be chosen by "the People of the several States". In 1961, the Twenty-third Amendment extended the right to choose electors to the District of Columbia.

Any U.S. citizen who resides in Puerto Rico (whether a Puerto Rican or not) is effectively disenfranchised at the national level. Although the Republican Party and Democratic Party chapters in Puerto Rico have selected voting delegates to the national nominating conventions participating in U.S. presidential primaries or caucuses, U.S. citizens not residing in one of the 50 states or in the District of Columbia may not vote in federal elections.

Various scholars (including a prominent U.S. judge in the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit) conclude that the U.S. national-electoral process is not fully democratic due to U.S. government disenfranchisement of U.S. citizens residing in Puerto Rico.[112][113]

As of 2010, under Igartúa v. United States, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is judicially considered not to be self-executing, and therefore requires further legislative action to put it into effect domestically. Judge Kermit Lipez wrote in a concurring opinion, however, that the en banc majority's conclusion that the ICCPR is non-self-executing is ripe for reconsideration in a new en banc proceeding, and that if issues highlighted in a partial dissent by Judge Juan R. Torruella were to be decided in favor of the plaintiffs, United States citizens residing in Puerto Rico would have a viable claim to equal voting rights .[111]

Congress has in fact acted in partial compliance with its obligations under the ICCPR when, in 1961, just a few years after the United Nations first ratified the ICCPR, it amended our fundamental charter to allow the United States citizens who reside in the District of Columbia to vote for the Executive offices. See U.S. Constitutional Amendment XXIII.51. Indeed, a bill is now pending in Congress that would treat the District of Columbia as "a congressional district for purposes of representation in the House of Representatives", and permit United States citizens residing in the capitol to vote for members of the House of Representatives. See District of Columbia House Voting Rights Act, S.160, 111th Congress (passed by the Senate, February 26, 2009) (2009).52 However, the United States has not taken similar "steps" with regard to the five million United States citizens who reside in the other U.S. territories, of which close to four million are residents of Puerto Rico. This inaction is in clear violation of the United States' obligations under the ICCPR".[111]

Accessibility

Federal legislation such as the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA), the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (NVRA, or "Motor-Voter Act") and the Help America Vote Act of 2001 (HAVA) help to address some of the concerns of disabled and non-English speaking voters in the United States.

Some studies have shown that polling places are inaccessible to disabled voters.[114] The Federal Election Commission reported that, in violation of state and federal laws, more than 20,000 polling places across the nation are inaccessible, depriving people with disabilities of their fundamental right to vote.

In 1999, the Attorney General of the State of New York ran a check of polling places around the state to see if they were accessible to voters with disabilities and found many problems. A study of three upstate counties of New York found fewer than 10 percent of polling places fully compliant with state and federal laws.[115]

Many polling booths are set in church basements or in upstairs meeting halls where there are no ramps or elevators. This means problems not just for people who use wheelchairs, but for people using canes or walkers too. And in most states people who are blind do not have access to Braille ballot to vote; they have to bring someone along to vote for them. Studies have shown that people with disabilities are more interested in government and public affairs than most and are more eager to participate in the democratic process. [114] Many election officials urge people with disabilities to vote absentee, however some disabled individuals see this as an inferior form of participation.[116]

Voter turnout is lower among the disabled. In the 2012 United States presidential election 56.8% of people with disabilities reported voting, compared to the 62.5% of eligible citizens without disabilities.[117]

Candidacy requirements

Jurisprudence concerning candidacy rights and the rights of citizens to create a political party are less clear than voting rights. Different courts have reached different conclusions regarding what sort of restrictions, often in terms of ballot access, public debate inclusion, filing fees, and residency requirements, may be imposed.

In Williams v. Rhodes (1968), the United States Supreme Court struck down Ohio ballot access laws on First and Fourteenth Amendment grounds. However, it subsequently upheld such laws in several other cases. States can require an independent or minor party candidate to collect signatures as high as five percent of the total votes cast in a particular preceding election before the court will intervene.

The Supreme Court has also upheld a state ban on cross-party endorsements (also known as electoral fusion) and primary write-in votes.

Noncitizen voting

More than 40 states or territories, including colonies before the Declaration of Independence, have at some time allowed noncitizens who satisfied residential requirements to vote in some or all elections. This in part reflected the strong continuing immigration to the United States. Some cities like Chicago, towns or villages (in Maryland) today allow noncitizen residents to vote in school or local elections.[118][56][119][Note 2] In 1875, the Supreme Court in Minor v. Happersett noted that "citizenship has not in all cases been made a condition precedent to the enjoyment of the right of suffrage. Thus, in Missouri, persons of foreign birth, who have declared their intention to become citizens of the United States, may under certain circumstances vote".[120] Federal law prohibits noncitizens from voting in federal elections.[121]

See also

Notes

- For state elections: Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966)

- See also Droit de vote des étrangers aux États-Unis (in French).

References

Citations

- U.S. Const. Art. I, s. 2, cl. 1.

- "One Person, One Vote | The Constitution Project". www.theconstitutionproject.com. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- Smith, J. Douglas (July 26, 2015). "The Case That Could Bring Down 'One Person, One Vote'". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- Goldman, Ari L. (November 21, 1986). "One Man, One Vote: Decades of Court Decisions". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "Baker v. Carr". Oyez. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "Wesberry v. Sanders". Oyez. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- "Watch John Oliver Cast His Ballot for Voting Rights for U.S. Territories". Time. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- Barck, Oscar T.; Lefler, Hugh T. (1958). Colonial America. New York: Macmillan. pp. 258–259.

- Barck, Oscar T.; Lefler, Hugh T. (1958). Colonial America. New York: Macmillan. pp. 259–260.

- "The History of Black Voting Rights—From the 1700s to Present Day—Originalpeople.org". originalpeople.org. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- "Expansion of Rights and Liberties - The Right of Suffrage". Online Exhibit: The Charters of Freedom. National Archives. Archived from the original on July 6, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- "U.S. Voting Rights". Infoplease. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- "Voting in Early America". Colonial Williamsburg. Spring 2007. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- Murrin, John M.; Johnson, Paul E.; McPherson, James M.; Fahs, Alice; Gerstle, Gary (2012). Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People (6th ed.). Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-495-90499-1.

- Free, Laura (2015). Suffrage Reconstructed: Gender, Race, and Voting Rights in the Civil War Era. Cornell University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-5017-0108-5.

- Stanley L. Engerman, University of Rochester and NBER; Kenneth L. Sokoloff, University of California, Los Angeles and NBER (February 2005). "The Evolution of Suffrage Institutions in the New World" (PDF): 16, 35.

By 1840, only three states retained a property qualification, North Carolina (for some state-wide offices only), Rhode Island, and Virginia. In 1856 North Carolina was the last state to end the practice. Tax-paying qualifications were also gone in all but a few states by the Civil War, but they survived into the 20th century in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Janda, Kenneth; Berry, Jeffrey M.; Goldman, Jerry (2008). The challenge of democracy : government in America (9. ed., update ed.). Houghton Mifflin. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-618-99094-8.

- "Voting Guide: How To Cast Your Vote, Participate In Government And Have Your Voice Heard". Congress Base. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- George W. Bush, et al., Petitioners v. Albert Gore, Jr., et al., Supreme Court of the United States, December 12, 2000, retrieved February 22, 2008

- U.S. Constitution Annotated, Justia, archived from the original on October 31, 2006, retrieved April 18, 2008

- Engerman, p. 8–9

- Engerman, p. 14. "Property- or tax-based qualifications were most strongly entrenched in the original thirteen states, and dramatic political battles took place at a series of prominent state constitutional conventions held during the late 1810s and 1820s."

- William G. Shade, "The Second Party System". in Paul Kleppner, et al. Evolution of American Electoral Systems (1983) pp 77-111

- Engerman, p. 16 and 35. Table 1

- Schultz, Jeffrey D.; Aoki, Andrew L.; Haynie, Kerry L.; McCulloch, Anne M. (2000). Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics: Hispanic Americans and Native Americans. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 528. ISBN 978-1-57356-149-5.

- Scher, Richard K. (March 4, 2015). The Politics of Disenfranchisement: Why is it So Hard to Vote in America?. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-317-45536-3.

- Schultz, Jeffrey D.; Aoki, Andrew L.; Haynie, Kerry L.; McCulloch, Anne M. (2000). Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics: Hispanic Americans and Native Americans. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 528. ISBN 978-1-57356-149-5.

- Scher, Richard K. (March 4, 2015). The Politics of Disenfranchisement: Why is it So Hard to Vote in America?. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-317-45536-3.

- "AP Tests: AP Test Prep: The Expansion of Suffrage". CliffsNotes. January 10, 2010. Archived from the original on January 10, 2010.

- Madsen, Deborah L., ed. (2015). The Routledge Companion to Native American Literature. Routledge. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-317-69319-2.

- The American Indian Vote: Celebrating 80 Years of U.S. Citizenship, Democratic Policy Committee, October 7, 2004, archived from the original on September 27, 2007, retrieved October 15, 2007

- Challenging American Boundaries: Indigenous People and the “Gift” of U.S. Citizenship. Cambridge University Press. 2004.

- Peterson, Helen L. (1957). "American Indian Political Participation". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 311: 116–126. doi:10.1177/000271625731100113. S2CID 144617127.

- "James Francis, Penobscot Tribal Historian, Indian Island". Portland Museum of Art. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- Maine State Museum 2019, p. 10.

- Press, Stanford University. "Ballot Blocked: The Political Erosion of the Voting Rights Act | Jesse H. Rhodes". www.sup.org. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- "Milestones in Voting History / Voting Rights and Citizenship".

- Registration and Voting by Absent Uniformed Services Voters and Overseas Voters in Elections for Federal Office, U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Voting Section, archived from the original on April 20, 2001, retrieved January 5, 2007

- Nur, Alio. "A Long History of Treaties". Native American Citizenship. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- Alio, Nur. "Native American Citizenship". nebraska studies.org. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- Alio, NUr. "Native American Citizenship". nebraska studies.org. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- "First Territorial Legislature of Alaska". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- "Citizenship for Native Veterans". Nebraska Studies. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- Cole 1992, p. 432.

- "Tillie Paul Tamaree & the Tlingit Community". Presbyterian Historical Society. September 17, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- "Tillie Paul Tamaree & the Tlingit Community". Presbyterian Historical Society. September 17, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- "SJ Names Place to Honor Tlingit Woman, Tillie Paul". Daily Sitka Sentinel. October 19, 1979. p. 5. Retrieved November 9, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cole 1992, p. 433.

- Cole 1992, p. 449.

- Tucker, Landreth & Lynch 2017, p. 330.

- Christen 2019, p. 98.

- Alaska Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 2018, p. 1.

- Tucker, Landreth & Lynch 2017, p. 336.

- Alaska Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 2018, p. 2.

- Tucker, Landreth & Lynch 2017, p. 342-343.

- Williamson, Chilton (1960), American Suffrage. From Property to Democracy, Princeton University Press

- Constitution of Delaware, 1776, The Avalon Project at Yale Law School, archived from the original on November 30, 2007, retrieved December 7, 2007

- State Constitution (Religious Sections)—Delaware, The Constitutional Principle: Separation of Church and State, retrieved December 7, 2007

- An Act for establishing the Constitution of the State of South Carolina, March 19, 1778, The Avalon Project at Yale Law School, archived from the original on December 13, 2007, retrieved December 5, 2007

- Constitution of Georgia; February 5, 1777, The Avalon Project at Yale Law School, archived from the original on December 13, 2007, retrieved March 27, 2008

- An Act for the relief of Jews in Maryland, passed February 26, 1825, Archives of Maryland, Volume 3183, Page 1670, February 26, 1825, retrieved December 5, 2007

- Francis Newton Thorpe (1898), The Constitutional History of the United States, 1765–1895, Harper & Brothers, ISBN 9780306719981, retrieved April 16, 2008

- Curtis, Benjamin Robbins (Justice). "Dred Scott v. Sandford, Curtis dissent". Legal Information Institute at Cornell Law School. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- Liebman, Bennett (August 28, 2018). "The Quest for Black Voting Rights in New York State". Albany Government Law Review. 11: 387.

The most important of the referenda held in New York in the nineteenth century were the three on the question of whether or not to remove the $250 property qualification requirement from Negro voters—a qualification which was not imposed on white voters since 1821.

- The Constitution of North Carolina, State Library of North Carolina, archived from the original on April 18, 2008, retrieved April 16, 2008

- Douglas, Stephen A. (1991). The Complete Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858. University of Chicago Press. p. 235.

- Alio, Nur. "African American Men Get the Vote". Cobb-LaMarche. Archived from the original on April 6, 2006.

- Rable, George C. (2007). But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-8203-3011-2.

- Gabriel J. Chin & Randy Wagner, "The Tyranny of the Minority: Jim Crow and the Counter-Majoritarian Difficulty", 43 Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 65 (2008)

- Gabriel J. Chin, "Reconstruction, Felon Disenfranchisement and the Right to Vote: Did the Fifteenth Amendment Repeal Section 2 of the Fourteenth?", 92 Georgetown Law Journal 259 (2004)

- Tillman, Benjamin (March 23, 1900). "Speech of Senator Benjamin R. Tillman". Congressional Record, 56th Congress, 1st Session. (Reprinted in Richard Purday, ed., Document Sets for the South in U. S. History [Lexington, MA.: D.C. Heath and Company, 1991], p. 147.). pp. 3223–3224.

- J. Morgan Kousser.The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974

- Glenn Feldman, The Disfranchisement Myth: Poor Whites and Suffrage Restriction in Alabama, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004, pp. 135–136

- Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary 17 (2000): 13-14, accessed March 10, 2008

- Scher, Richard K. (2015). The Politics of Disenfranchisement: Why is it So Hard to Vote in America?. Routledge. p. viii-ix. ISBN 9781317455363.

- "Civil Rights in America: Racial Voting Rights" (PDF). A National Historic Landmarks Theme Study. 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ward, Geoffrey C. (1996). The West : an illustrated history. Duncan, Dayton. (1st ed.). Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-92236-6. OCLC 34076431.

- "Race, Nationality, and Reality". National Archives. August 15, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- "Our Documents - Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)". www.ourdocuments.gov. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- "Our Documents - Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)". www.ourdocuments.gov. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- "FONG, Hiram Leong | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- "Milestones: 1945–1952 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- "Our Documents - Voting Rights Act (1965)". www.ourdocuments.gov. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- Bureau, US Census. "Historical Reported Voting Rates". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- alio, nur. "women". Women's Rights Movement in the U.S. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- James, Randy (February 26, 2009). "A Brief History of Washington, D.C." Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- Weiser, Carl (April 18, 2004), Should voting age fall to 16? Several states ponder measure., The Enquirer, retrieved January 5, 2008

- "Felony Disenfranchisement Laws in the United States" (PDF). The Sentencing Project. March 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 19, 2012.

- Gonchar, Michael. "Should Felons Be Allowed to Vote After They Have Served Their Time?".

- "State toughens policy of restoring rights to freed felons" Archived October 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Tampa Bay Times, August 8, 2011

- Gramlich, John (September 23, 2008). "Groups push to expand ex-felon voting". Stateline.org. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- Kelly, Jon (February 10, 2011). "Would prisoners use their votes?". Retrieved April 9, 2019; "Q&A: UK prisoners' right to vote". January 20, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- "Can prisoners vote or not?", Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, September 19, 2008, accessed October 1, 2008.

- U.S.: 700.23 per 100,000 inhabitants (2002); versus, for example, Belarus (516.25 per 100,000 inhabitants); South Africa (401.24 per 100,000 inhabitants); Latvia (362.83 per 100,000 inhabitants) Eighth United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems, covering the period 2001–2002 (PDF), United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, retrieved October 2, 2008 (Table 15.1, Total persons incarcerated, with incarceration rates for some nations (e.g., Russia and China) unreported)

- "ICPS :School of Law :King's College London : World Prison Brief : King's College London". January 26, 2009. Archived from the original on January 26, 2009.

- Pilkington, Ed (July 13, 2012). "Felon voting laws to disenfranchise historic number of Americans in 2012". The Guardian. Retrieved August 7, 2013.