2019–20 Hong Kong protests

The 2019–20 Hong Kong protests, also known as Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement (Chinese: 反對逃犯條例修訂草案運動), were triggered by the introduction of the Fugitive Offenders amendment bill by the Hong Kong government. The bill would have allowed extradition to jurisdictions with which Hong Kong did not have extradition agreements, including mainland China and Taiwan. This led to concerns that Hong Kong residents and visitors would be exposed to the legal system of mainland China, thereby undermining Hong Kong's autonomy and infringing civil liberties. It set off a chain of protest actions that began with a sit-in at the government headquarters on 15 March 2019, a demonstration attended by hundreds of thousands on 9 June 2019, followed by a gathering outside the Legislative Council Complex to stall the bill's second reading on 12 June which escalated into violence that caught the world's attention.

| 2019–2020 Hong Kong Protests | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of democratic development in Hong Kong, Hong Kong–Mainland China conflict and the Chinese democracy movement | |||

.jpg.webp)     .jpg.webp) .jpg.webp) Various protest scenes in Hong Kong Clockwise from top:

| |||

| Date | 15 March 2019[1] – late 2020[under discussion] | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Goals | Five Demands

| ||

| Methods | Diverse (see § Tactics and methods) | ||

| Resulted in | Government crackdown

| ||

| Concessions given | |||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| Deaths, injuries and arrests | |||

| Death(s) | 2 | ||

| Injuries |

| ||

| Arrested | 10,200 (as of 2 February 2021)[24][lower-alpha 2] | ||

| Charged | 2,450 (as of 2 February 2021)[24] | ||

| Property damage | HK$5.35 billion+ (US$755 million+) [27][28][29] | ||

| 2019–20 Hong Kong protests | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 反對逃犯條例修訂草案運動 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 反对逃犯条例修订草案运动 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| 2019–20 Hong Kong protests |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Part of the Democratic development in Hong Kong |

| Background |

| Protests timeline |

|

2019 2020 |

| Tactics and methods |

| Incidents |

| Fatalities |

| Reactions |

| See also |

|

On 16 June, just one day after the Hong Kong government suspended the bill, an even bigger protest took place to push for its complete withdrawal and in reaction to the perceived excessive use of force by the police on 12 June. As the protests progressed, activists laid out five key demands, namely the withdrawal of the bill, an investigation into alleged police brutality and misconduct, the release of all the arrested, a retraction of the official characterisation of the protests as "riots", and the resignation of Carrie Lam as chief executive along with the introduction of universal suffrage in the territory. Police inaction when suspected triad members assaulted protesters and commuters in Yuen Long on 21 July and the police storming of Prince Edward station on 31 August further escalated the protests.

Lam withdrew the bill on 4 September, but refused to concede the other four demands. Exactly one month later, she invoked the emergency powers to implement an anti-mask law, to counterproductive effect. Confrontations escalated and intensified – police brutality and misconduct allegations increased, while some protesters started using petrol bombs and vandalising pro-Beijing establishments and symbols representing the government. Rifts within society widened and activists from both sides assaulted each other. The storming of the Legislative Council in July 2019, the deaths of Chow Tsz-lok and Luo Changqing, the shooting of an unarmed protester, and the sieges of two universities in November 2019 were landmark events.

After the conflict at Chinese University and siege of the Polytechnic University, the unprecedented landslide victory of the pro-democracy camp in the District Council election in November and the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 brought a little respite. Tensions mounted again in May 2020 after Beijing's decision to promulgate a national security bill for Hong Kong before September. This was criticised by many as a threat to fundamental political freedoms and civil liberties ostensibly enshrined in the Hong Kong Basic Law, and prompted some in the international community to re-evaluate their policies towards Hong Kong, which they deemed as no longer autonomous.

The approval ratings of the government and the police plunged to the lowest point since the 1997 handover; the Central People's Government alleged that foreign powers were instigating the conflict, although the protests have been largely described as "leaderless". The United States passed the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act on 27 November 2019 in response to the protest movement. The tactics and methods used in Hong Kong inspired other protests in 2019.

Background

Direct cause

The Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill 2019 was first proposed by the government of Hong Kong in February 2019 in response to the 2018 murder of Poon Hiu-wing by her boyfriend Chan Tong-kai in Taiwan, which the two Hong Kongers were visiting as tourists. As there is no extradition treaty with Taiwan (because the government of China does not recognise Taiwan's sovereignty), the Hong Kong government proposed an amendment to the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance (Cap. 503) and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Ordinance (Cap. 525) to establish a mechanism for case-by-case transfers of fugitives, on the order of the chief executive, to any jurisdiction with which the city lacks a formal extradition treaty.[30]

The inclusion of mainland China in the amendment is of concern to Hong Kong society; citizens, academics and the legal profession fear the removal of the separation of the region's jurisdiction from the legal system administered by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) would erode the "one country, two systems" principle in practice since the 1997 handover; furthermore, Hong Kong citizens lack confidence in China's judiciary system and human rights protection due to its history of suppressing political dissent.[31] Opponents of the bill urged the Hong Kong government to explore other mechanisms, such as an extradition arrangement solely with Taiwan, and to sunset the arrangement immediately after the surrender of the suspect.[30][32]

Underlying causes

The 2019–20 Hong Kong protests came four and a half years after the Umbrella Revolution of 2014 which begun after the decision of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPCSC) regarding proposed reforms to the Hong Kong electoral system, which were largely seen as restrictive. However, the movement ended in failure as the government offered no concessions.[33] Since then, democratic development has stalled: only half of the seats in the Legislative Council remain directly elected, and the chief executive of Hong Kong continues to be elected by the small-circle Election Committee. The 2017 imprisonment of Hong Kong democracy activists further dashed the city's hope of meaningful political reform.[34] Citizens began to fear the loss of the "high degree of autonomy" as provided for in the Hong Kong Basic Law, as the government of the People's Republic of China appeared to be increasingly and overtly interfering with Hong Kong's affairs. Notably, the NPCSC saw fit to rule on the disqualification of six lawmakers; fears over state-sanctioned rendition and extrajudicial detention were sparked by the Causeway Bay Books disappearances.[35][34] The general trend of the loss of freedoms in Hong Kong is marked by its steady fall on the Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index.[36][37] Xi Jinping's accession to paramount leader of China in 2012 marked a more hardline authoritarian approach, most notably with the construction of concentration camps in Xinjiang. The spectre that Hong Kong may similarly be brought to heel became an important element in the protests.[38]

Anti-mainland sentiment had begun to swell in the 2010s. The daily quota of 150 immigrants from China since 1997, and the massive flows of mainland visitors strained Hong Kong's public services and eroded local culture; mainlanders' arrogance drew the scorn of Hongkongers.[38] The rise of localism and the pro-independence movement during the tenure of CY Leung as chief executive was marked by the high-profile campaign for the 2016 New Territories East by-election by activist Edward Leung.[39] As fewer and fewer young people in Hong Kong identified themselves as Chinese nationals, pollsters at the University of Hong Kong found that the younger respondents were, the more distrustful they were of the Chinese government.[35] Scandals and corruption in China shook people's confidence of the country's political systems; the Moral and National Education controversy in 2012 and the Express Rail Link project connecting Hong Kong with mainland cities and the subsequent co-location agreement proved highly controversial. Citizens saw these policies as Beijing's decision to strengthen its hold over Hong Kong. By 2019, almost no Hong Kong youth identified themselves as Chinese.[40]

The polite Umbrella Revolution had provided inspiration and brought about a political awakening to some,[33][41] but its failure and the subsequent split within the pro-democratic bloc prompted a re-evaluation of strategy and tactics. In the years that followed, the general consensus emerged that peaceful and polite protests were ineffective in advancing democratic development, and became an example of what not to do in further protests. Media noted that protests in 2019 were driven by a sense of desperation rather than the optimism in 2014.[42][43] The aims of the protests had evolved from withdrawing the bill, solidifying around achieving the level of freedom and liberties promised.[44]

Economic factors were also cited as an underlying cause of anger among Hongkongers.[45][46][47] With powerful business cartels, Hong Kong suffers from income disparity[48] – having the second highest Gini coefficient in the world in 2017[49] – and a shortage of affordable housing for the territory's population.[50][51] Youth, who have been pre-eminent in the protests, are frustrated by low social mobility and the lack of job opportunities;[48][52] salaries for university graduates in 2018 were lower than those of 30 years previously.[48] Many protesters in Hong Kong were young and educated; many of them were under the age of 30, and had received tertiary education.[53]

Objectives

Initially the protesters only demanded the withdrawal of the extradition bill. Following an escalation in the severity of policing tactics against demonstrators on 12 June 2019, the protesters' objective was to achieve the following five demands (under the slogan "Five demands, not one less"):[54]

- Complete withdrawal of the extradition bill from the legislative process: Although the chief executive announced an indefinite suspension of the bill on 15 June, its status of "pending resumption of second reading" in the Legislative Council meant that its reading could have been resumed quickly. It was formally withdrawn on 23 October 2019.[55]

- Retraction of the "riot" characterisation: The government originally characterised the 12 June protest as "riots", it later amended the description to say there were "some" rioters, an assertion protesters still contest. The crime of "rioting" carries a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison.

- Release and exoneration of arrested protesters: Protesters consider their lawbreaking acts to be mostly motivated by a politically righteous cause; they also question the legitimacy of police arresting protesters at hospitals through access to their confidential medical data in breach of patient privacy.

- Establishment of an independent commission of inquiry into police conduct and use of force during the protests: Civic groups felt that the level of violence used by the police against protesters and bystanders, arbitrary stop-and-search,[56] and officers' failure to observe Police General Orders pointed to a breakdown of accountability.[57] The absence of independence of the existing watchdog, the Independent Police Complaints Council, is also an issue.[58]

- Resignation of Carrie Lam and the implementation of universal suffrage for Legislative Council elections and for the election of the chief executive:[59] The chief executive is selected in a small-circle election, and 30 of the 70 legislative council seats are filled by representatives of institutionalised interest groups, forming the majority of the so-called functional constituencies, most of which have few electors.

History

Early large-scale demonstrations

After several minor protests in March and April 2019.[60] the anti-extradition issue attracted more attention when pro-democratic lawmakers in the Legislative Council launched a filibuster campaign against the bill. In response, the Secretary of Security John Lee announced that the government would resume second reading of the bill in full council on 12 June 2019, bypassing the Bills Committee, whose role would have been to scrutinise it.[61] With the possibility of a second reading of the bill, the Civil Human Rights Front (CHRF), a platform for 50 pro-democracy groups, launched their third protest march on 9 June. While police estimated attendance at the march on Hong Kong Island at 270,000, the organisers claimed that 1.03 million people had attended the rally.[62][63] Carrie Lam insisted second reading and debate over the bill be resumed on 12 June.[64] Protesters successfully stopped the LegCo from resuming second reading of the bill by surrounding the LegCo Complex.[65] Police Commissioner Stephen Lo declared the clashes a "riot".,[66] but they were subsequently criticised for using excessive force, such as firing tear gas at protesters at an approved rally,[67][68] and for the lack of identification numbers on police officers' uniforms.[69] Following the clashes, protesters began calling for an independent inquiry into police brutality; they also urged the government to retract the "riot" characterisation.

On 15 June, Carrie Lam announced the bill's suspension but did not fully withdraw it.[70] A 35-year-old man named Marco Leung Ling-kit committed suicide in protest of Lam's decision and police brutality on June 12.[71] His anti-extradition slogans later became the foundations for the "five demands" of the protests, and his yellow raincoat became one of the symbols of the protests.[72] On the following day, CHRF claimed that 2 million people had participated in the 16 June protest, while the police estimated that there were 338,000 demonstrators at its peak.[73] Lam officially apologised to the public on 18 June two days after another massive march, but ignored calls for resign.[74]

Storming of the Legislative Council and escalation

The CHRF claimed a record turnout of 550,000 for their annual march on 1 July 2019, while police estimated around 190,000 at the peak;[75][76] an independent polling organisation estimated attendance at 260,000.[77] The protest was largely peaceful. At night, partly angered by several more suicides since 15 June 2019, some radical protesters stormed into the Legislative Council; police took little action to stop them.[78][79][80]

After 1 July 2019, protests spread to different areas in Hong Kong such as Sheung Shui, Sha Tin and Tsim Sha Tsui.[81][82][83] CHRF held another anti-extradition protest on 21 July on Hong Kong Island. Instead of dispersing, protesters headed for the Liaison Office in Sai Ying Pun, where they defaced the Chinese national emblem.[84] While a standoff between the protesters and the police occurred on Hong Kong Island,[85] groups of white-clad individuals, suspected triad members, appeared and indiscriminately attacked people inside Yuen Long station.[86] Police were absent during the attacks, and the local police stations were shuttered, leading to suspicion that the attack was coordinated with police. Pro-Beijing lawmaker Junius Ho was later seen greeting members of the group, which led to accusations that he approved of the attack.[86] The attack was often seen as the turning point for the movement, as it crippled people's confidence in the police and turned a lot of citizens who were politically neutral or apathetic against the police.[87]

A call for a general strike on 5 August was answered by about 350,000 people according to the Confederation of Trade Unions;[88] over 200 flights had to be cancelled.[89][90][91] Protests were held in seven districts in Hong Kong. Protesters in North Point were attacked by a group of stick-wielding men of Fujianese origin, leading to violent clashes.[92][93]

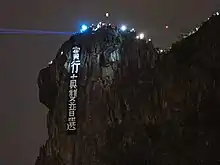

.jpg.webp)

Various incidents involving alleged police brutality on 11 August—police shot bean bag rounds that ruptured the eye of a female protester, the use of tear gas indoors, the deployment of undercover police as agents provocateurs, and the firing of pepper ball rounds at protesters at a very close range—prompted protesters to stage a three-day sit-in at Hong Kong International Airport from 12 to 14 August, forcing the Airport Authority to cancel numerous flights.[96][97][98] On 13 August, protesters at the airport cornered, tied up and assaulted two men they accused of being either undercover police or agents for the mainland, who were later identified as a tourist and a Global Times reporter.[99][100] A peaceful rally was held in Victoria Park by the CHRF on 18 August to denounce police brutality. The CHRF claimed attendance of at least 1.7 million people.[101] On 23 August, an estimated 210,000 people participated in the "Hong Kong Way" campaign to draw attention to the movement's five demands. The chain extended across the top of Lion Rock.[102]

Ignoring a police ban, thousands of protesters took to the streets of Hong Kong Island on 31 August following the arrests of high-profile pro-democracy activists and lawmakers the previous day.[103][104][105] At night, the Special Tactical Squad stormed Prince Edward station, where they beat and pepper-sprayed the commuters inside.[106] Protesters rallied outside the Mong Kok police station in the following weeks to condemn police brutality and demanded the MTR Corporation release the CCTV footage of that night as rumours began to circulate on the internet that the police's operation had caused death, which they denied.[107][108]

Decision to withdraw the extradition bill

On 4 September, Carrie Lam announced the formal withdrawal of the extradition bill once Legco reconvened in October and the introduction of additional measures to calm the situation. However, protests continued to insist on all five demands being met.[109] During the month, protesters organised various flash mob rallies to sing the protest anthem "Glory to Hong Kong".[110][111] They continued their attempts to disrupt the airport's operations,[112] and held pop-up mall protests, which targeted shops and corporations perceived to be pro-Beijing.[113] Carrie Lam held the first public meeting in Queen Elizabeth Stadium in Wan Chai with 150 members of the public. Protesters demanding to talk to her surrounded the venue, though Lam declined meeting with them.[114]

On 1 October 2019, mass protests and violent conflict occurred between the protesters and police in various districts of Hong Kong during the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China. This resulted in the first use of live rounds by police. One 18-year-old student protester was shot in the chest by police in Tsuen Wan while trying to hit a policeman with a rod.[115][116][117] Carrie Lam invoked the Emergency Regulations Ordinance to impose a law to ban wearing face masks in public gatherings, attempting to curb the ongoing protests on 4 October.[118] The law's enactment was followed by continued demonstrations in various districts of Hong Kong, blocking major thoroughfares, vandalising shops perceived to be pro-Beijing and paralysing the MTR system.[119][120][121] Protests and citywide flash mob rallies persisted throughout the month.[122][123]

Intensification and sieges of the universities

Protesters clashed with the police late at night on 3 November 2019. Alex Chow Tsz-lok, a 22-year-old student at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST), was later found unconscious on the second floor of the estate's car park. He died on 8 November following two unsuccessful brain surgeries.[124][125] After his death, protesters engaged in flash mob rallies against the police and attended vigils in various districts of Hong Kong. They blamed the police for his death, though the police denied any involvement.[126] In response to Chow's death, protesters planned a city-wide strike starting on 11 November by disrupting transport in the morning in various districts of Hong Kong.[127] That morning, a policeman fired live rounds in Sai Wan Ho, wounding an unarmed 21-year-old.[128] On 14 November, an elderly man named Luo Changqing died from a head injury which he had sustained the previous day during a confrontation between two groups of anti-government protesters and residents in Sheung Shui.[129][130]

.jpg.webp)

For the first time, during a standoff on 11 November, police shot numerous rounds of tear gas, sponge grenades and rubber bullets into the campuses of universities, while protesters threw bricks and petrol bombs in response.[131] Student protesters from the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) confronted the police for two consecutive days.[132] After the conflict, protesters briefly occupied several universities.[133][134] A major conflict between protesters and police took place in Hung Hom on 17 November after protesters took control of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) and blockaded the Cross-Harbour Tunnel. Thus began the siege of PolyU by police which ended with them storming onto the campus and arresting several protesters and volunteer medics in the early morning of 18 November.[135][136] With PolyU under complete lockdown by police, protesters outside the campus attempted to penetrate police cordons to break through to those trapped inside but were repelled by police.[137] Police action in Yau Ma Tei resulted in a stampede.[138] More than 1,100 people were arrested in and around PolyU over the course of the siege.[139][140] The siege was ended on 29 November.[141]

Electoral landslide and COVID-19

.jpg.webp)

The 24 November 2019 District Council election, considered a referendum on the government and the protests, attracted a record high voter turnout.[142] The results saw the pro-democracy camp win by a landslide, with the pro-Beijing camp suffering their greatest electoral defeat in Hong Kong's history.[143][144] The unprecedented electoral success of the pro-democracy voters, the mass arrests during the PolyU siege, and faster response by police contributed to a decrease in the intensity and frequency of the protests in December 2019 and January 2020.[145] Despite this, the CHRF organised two marches to maintain pressure on the government on December 8, 2019 and January 1, 2020, attracting 800,000 protesters and 1,030,000 protesters respectively.[146][147]

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in mainland China caused the number of large-scale rallies to dwindle further because of fears that they might facilitate the spread of the virus. Despite this, the pro-democratic movement's tactics were repurposed to pressure the government to take stronger actions to safeguard Hong Kong's public health in the face of the coronavirus outbreak in Hong Kong.[148] Protesters demanded all mainland travellers be banned from entering Hong Kong. From 3 to 7 February 2020, hospital staff launched a labour strike with the same goal.[149][150] The strike was partially successful as Lam, despite rejecting a full border closure, only left three of the 14 crossing points with mainland China open.[151] As the coronavirus crisis escalated in February and March 2020, the scale of the protests dwindled further.[152][153] Police have used coronavirus laws banning groups of more than four, for example, to disperse protesters.[154][155] On 18 April, police arrested 15 pro-democracy activists including Jimmy Lai, Martin Lee and Margaret Ng for their activities in 2019, drawing international condemnation.[156] On 15 May, a 22-year-old young man surnamed Sin was sentenced to four years in prison for his participation in the 12 June protest, becoming the first person to be jailed for the charge of rioting since the protest movement started.[157]

Implementation of the national security law

On 21 May 2020, state media announced that the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPCSC) would begin drafting a new law that covers "secession, foreign interference, terrorism and subversion against the central government", to be added into the Annex III of the Hong Kong Basic Law. This meant that the law would come into effect through promulgation, bypassing local legislation.[158] The UK, along with Australia, Canada, and the US, also issued a joint statement expressing their deep concern regarding the National Security Law on 28 May as they deemed that the law breached the Sino-British Joint Declaration and undermined the implementation of the "one country, two systems" principle.[159] Despite international pressure, the NPCSC passed the national security legislation that day.[160][161] The draft sparked increased protests: the mass march on 24 May in Causeway Bay was the largest protest since the beginning of the pandemic, as civilians responded to online calls to march against both the National Anthem Bill and the proposed national security law.[162] On 27 May at least 396 people were arrested during a day-long protest; most of the arrested were taken into custody even before any protest actions had begun.[163]

.jpg.webp)

On 30 June, the NPCSC passed the national security law unanimously, without informing the public and the local officials of the content of the law.[165] The law created a chilling effect in the city. Demosistō, which had been involved in lobbying for other nations' support, and several pro-independent groups announced that they had decided to disband and cease all operations, fearing that they would be the targets of the new law.[166] Thousands of protesters showed up on July 1 to protest against the newly implemented law. On that day, the police arrested at least ten people for breaching national security as they deemed that individuals who displayed or possessed flags, placards and phone stickers with protest slogans or other protest art have already committed the crime of "subverting the country".[167]

Following the implementation of the national security law, the international community reassessed their policies towards China. Major countries in the West (Canada, the US, the UK, Australia, Germany and New Zealand) suspended its extradition treaty with Hong Kong over the introduction of the national security law.[168][169][170][171][172] The US Congress passed the Hong Kong Autonomy Act and president Donald Trump signed an Executive Order to revoke the city's special trade status after Mike Pompeo informed the Congress that Hong Kong was no longer autonomous from China and so should be considered the same country in trade and other such matters.[173] On 7 August, the US announced that they would impose sanctions on eleven Hong Kong and Chinese top officials, including Carrie Lam, for undermining Hong Kong's freedom and autonomy.[174] British Home Office announced that starting from early 2021, current and former holders of the BN(O) passport in Hong Kong can resettle in the UK along with their dependents for five years before they become eligible to apply for permanent citizenship.[175]

Subsequent clampdown

Invigorated by its success in the November 2019 District Council election, the pro-democratic bloc was eyeing to win over half of the 70 seats in the Legislative Council in the election set to be held on 6 September.[176] Some members from the pro-democratic camp, in particular, the more radical democrats, promised to use all constitutional powers of LegCo members to force the government to concede and respond to all of the five demands.[177] Unfazed by the national security law, more than 600,000 people cast their votes in the bloc's historic first primaries in mid July 2020. The Hong Kong government then disqualified twelve candidates on 30 July, nearly all of whom were winners from the pro-democratic primaries. Four of whom were incumbent lawmakers.[178][179] The decision drew international condemnation for obstructing the election and the democratic process.[180] On the following day, Carrie Lam, going against the public opinion,[181] invoked emergency powers to delay the election to September 2021, citing the pandemic as the reason. The NPCSC passed a motion to extend the incumbent 6th Legislative Council (which has a pro-Beijing majority) for no less than one year. While the NPCSC allowed the four disqualified incumbent lawmakers to transition to the extended term in July, they decided to remove them from office in November 2020, resulting in the mass resignation of all of opposition lawmakers.[182]

.jpg.webp)

The police continued to use the law to target local activists and critics of Beijing, including business tycoon Jimmy Lai, former Demosisto member Agnes Chow, pro-independent activist Tony Chung and People's Power vice-president Tam Tak-chi. Arrest warrants were issued to exiled activists for breaching the national security law, including former lawmakers Nathan Law, Baggio Leung and Ted Hui, former British consulate employee Simon Cheng, pro-independence activist Ray Wong, and United States activist Samuel Chu, with the arrest warrant of Chu being the first case of extraterritorial jurisdiction that is claimed by the law.[183][184] Twelve Hong Kong activists who were released on bail were captured by China's Coast Guard Bureau while fleeing to Taiwan on a speedboat on August 23. Detained in Yantian, Shenzhen, they were subsequently charged with crossing the Chinese border illegally and were prevented from choosing their lawyers and meeting their families.[185][186] Meanwhile, democracy campaigner Joshua Wong and fellow activists Agnes Chow and Ivan Lam were jailed by a court in West Kowloon and were sentenced to 7 to 13 months in prison.[187]

As protest activities dwindled, the government continued to tighten its control in Hong Kong, from censoring school textbooks and removing any mention of the Tiananmen massacre,[188] to removing public examination questions which the authorities deemed politically inappropriate,[189] to deregistering "yellow-ribbon" teachers,[190] to declaring that separation of powers never existed in Hong Kong despite previous comments by the city's top judges recognising its importance in Hong Kong.[191] It also attempted to reshape the narrative of the Yuen Long attack by claiming that the attack had not been indiscriminate, changing the officially reported police response time, and arresting Lam Cheuk-ting, a pro-democracy lawmaker who was hurt in the attack, for "rioting".[192] In August 2020, the Department of Justice, under the leadership of Teresa Cheng, intervened and dismissed private prosecutions launched by pro-democracy activists against the police or pro-Beijing individuals.[193] In January 2021, the police arrested more than 50 individuals, all of whom were candidates in the primaries for "subverting state power".[194] This meant that most of the active and prominent politicians in the opposite camp in Hong Kong have been arrested by the authorities using the national security law.[195]

Clashes between protesters and counter-protesters

Clashes between protesters and counter-protesters had become more frequent since the movement began in June 2019. During a pro-police rally on 30 June, their supporters began directing profanities at their opposition counterparts and destroyed their Lennon Wall and the memorial for Marco Leung, leading to intense confrontations between the two camps.[197] Pro-Beijing citizens, wearing "I love HK police" T-shirts and waving the Chinese national flag, assaulted people perceived to be protesters on 14 September in Fortress Hill.[198] Lennon Walls became sites of conflict between the two camps, with pro-Beijing citizens attempting to tear down the messages or removing poster art.[199][200] Some protesters and pedestrians were beaten and attacked with knives near Lennon Walls by a single perpetrator[201][202] or by suspected gang members.[203] A reporter was stabbed and a teenager distributing pro-protest leaflets had his abdomen slashed.[204] Owners of small businesses seen to be supportive of the protests and their employees have been assaulted in suspected politically motivated attacks and their businesses vandalised.[205][206]

Some civilians allegedly attempted to ram their cars into crowds of protesters or the barricades they set up.[207][208] In one instance, a female protester suffered severe thigh fractures.[209] Protest organisers, including Jimmy Sham from the CHRF, and pro-democratic lawmakers such as Roy Kwong were assaulted and attacked.[210][211][212] On 3 November, politician Andrew Chiu had his ear bitten off by a Chinese mainlander who had reportedly knifed three other people outside Cityplaza.[213][214] Meanwhile, pro-Beijing lawmaker Junius Ho was stabbed and his parent's grave was desecrated.[215][216]

The 2019 Yuen Long attack occurred following a mass protest organised by the CHRF on 21 July. Suspected gangsters vowed that they would "defend" their "homeland" and warned all anti-extradition bill protesters not to set foot in Yuen Long.[217] Perpetrators were indiscriminately attacking commuters in the concourse and on the platform of Yuen Long station, as well as inside train compartments, resulting in a widespread backlash from the community. The Department of Justice has since been criticised by some lawyers for making "politically motivated" prosecutions. After the Yuen Long attack, no assailant was charged for weeks after the event, while young protesters were charged with rioting within several days.[218] Protesters were also attacked with fireworks in Tin Shui Wai on 31 July,[219] and then attacked by knife-wielding men in Tsuen Wan[220] and suspected "Fujianese" gang members wielding long poles in North Point on 5 August, though they fought back against the attackers.[221][222]

Amidst frustration that police had failed to prosecute pro-government violent counter-protesters and being increasingly distrustful of police because of this,[223] hard-core protesters began to carry out vigilante attacks—described by protesters as "settling matters privately" —targeting individuals perceived to be foes.[223][224] Pro-Beijing actress Celine Ma,[225] plainclothed officers,[226] and a taxi driver who drove into a crowd of protesters in Sham Shui Po on 8 October, were attacked.[227] A middle-aged man was doused with flammable liquid and set on fire by a protester after he had an altercation with protesters at Ma On Shan station on 11 November.[228][229] On 14 November, an elderly man died from head injuries sustained earlier during a violent confrontation between two groups of protesters and Sheung Shui residents.[230]

Tactics and methods

.svg.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The protests have been described as being largely "leaderless".[231] No group or political party has claimed leadership over the movement, though civic groups and prominent politicians have played a supportive role, such as applying for Letters of No Objection from the police or mediating conflicts between protesters and police officers.[232] Protesters commonly used LIHKG, an online forum similar to Reddit, as well as Telegram, an optionally end-to-end encrypted messaging service to communicate and brainstorm ideas for protests and to make collective decisions.[231] Unlike previous protests, those of 2019 spread over 20 different neighbourhoods, so the entire territory witnessed them.[233] Protesters and their supporters remained anonymous to avoid prosecutions or future potential retaliation from the authorities, employers who had a different political orientation, and corporations which kowtowed to political pressure.[234]

For the most part there are two groups of protesters, namely the "peaceful, rational and non-violent" protesters and the "fighters" group.[235] Nonetheless, despite differences in methods, both groups have refrained from denouncing or criticising the other and provided tacit support. The principle was the "Do Not Split"— praxis—which was aimed to promote mutual respect for different views within the same protest movement. This was a response to the failure of the Umbrella Revolution which fell apart partly due to internal conflicts within the pro-democratic bloc.[236][38]

Moderate group

The moderate group participated in different capacities. The peaceful group held mass rallies, flash mobs, and engaged in other forms of protest such as hunger strikes,[237] forming human chains,[238] launching petitions,[239] labour strikes,[240] and class boycotts.[241][242] Lennon Walls were set up in various neighbourhoods to spread messages of support and display protest art.[243][244] Protesters had set up pop-up stores that sold cheap protest gadgets,[245] provided undercover clinics for young activists,[246] and crowdfunded to help people in need of medical or legal assistance.[247]

To raise awareness of their cause and to keep citizens informed, artists supporting the protest created protest art and derivative works, many of which mock the police and the government.[248] Twitter and Reddit were used to deliver information about the protests to raise awareness to users abroad,[249][250] while platforms like Facebook and Instagram were employed to circulate images of police brutality.[251] Protesters held "civil press conferences" to counter press conferences by police and the government.[252] AirDrop was used to broadcast anti-extradition bill information to the public and mainland tourists.[253] A protest anthem, "Glory to Hong Kong", was composed, its lyrics crowdsourced on the LIHKG online forum, and sung by flash mobs in shopping centres.[254] The Lady Liberty Hong Kong statue was also crowdfunded by citizens to commemorate the protests.[255]

Protesters have attempted to gain international support. Activists organised and coordinated numerous rallies to this end.[256][257] Joshua Wong, Denise Ho and several other democrats provided testimonies during the US congressional hearing for the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act.[258] To increase the political pressure on China, they also advocated for the suspension of the United States–Hong Kong Policy Act, which grants Hong Kong's special status as the city is considered as a separate entity from mainland China for matters concerning trade export and economics control after the 1997 handover.[259] Advertisements on the protestors' cause were financed by crowdfunding and placed in major international newspapers in July 2019, ahead of the G20 summit in Osaka;[260] two further advertising campaigns followed until 12 August 2019.[261] At events, protesters waved the national flags of other countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, calling for their support.[262]

Efforts were made to transform the protests into a long-lasting movement. Protesters have advocated a "Yellow Economic Circle".[263] Supporters of the protesters labelled different establishments based on their political stance and chose to patronise only in businesses which are sympathetic to the movement, while boycotting businesses supporting or owned by mainland Chinese interests.[264][265] Flash mob rallies were held in the central business districts as office workers used their lunch break to march on the street.[266] The protests prompted various professions to set up labour unions that compete with pro-Beijing lobbies to pressure the government further.[267] Newly elected District Council members put forward motions to condemn the police and used their power to assist the detained protesters.[268] Pro-democratic lawmakers also put forward a motion to impeach Lam, though it was rejected by the pro-Beijing lawmakers in December 2019.[269]

Radical group

Radical protesters adopted the "be water" strategy, inspired by Bruce Lee's philosophy, often moving in a fluid and agile fashion to confound and confuse the police.[272] They often retreated when police arrived, only to re-emerge elsewhere.[273] In addition, protesters adopted black bloc tactics to protect their identities. Frontliners' "full gear" consisted of umbrellas, face masks, hard hats and respirators to shield themselves from projectiles and teargas.[274] Furthermore, protesters used laser pointers to distract police officers and interfere with the operation of their cameras.[274] At protest scenes, protesters used hand gestures for nonverbal communication, and supplies were delivered via human chains.[275] Different protesters adopted different roles. Some were "scouts" who shared real-time updates whenever they spotted the police,[276][277] while others were "firefighters" who extinguished tear gas with kitchenware and traffic cones.[278] A mobile app was developed to allow crowdsourcing the location of police.[279]

Starting in August 2019, radical protesters escalated the controversial use of violence and intimidation. They dug up paving bricks and threw them at police; others used petrol bombs, corrosive liquid and other projectiles against police. Petrol bombs were also hurled by protesters at police stations and vehicles.[280][281][121] As a result of clashes, there were multiple reports of police injuries and the assault of officers throughout the protests.[282][283] One officer was slashed in the neck with a box cutter,[122] and a media liaison officer was shot in the leg with an arrow during the PolyU siege.[284] The police also accused the protesters of intending to "kill or harm" police officers after a remote-controlled explosive device detonated on 13 October near a police vehicle.[285] Protesters also directed violence towards undercover officers suspected to be agents provocateurs.[286][287] Several individuals were arrested for illegal possession of firearms or making homemade explosives.[288]

Unlike other civil unrests, little random smashing and looting were observed, as protesters vandalised targets they believed embodied injustice.[289] Corporations that protesters accused of being pro-Beijing, mainland Chinese companies, and shops engaging in parallel trading, were also vandalised, subject to arson or spray-painted.[290][291][292][293] Protesters also directed violence at symbols of the government by vandalising government and pro-Beijing lawmakers' offices,[294][295] and defacing symbols representing China.[296][224] The MTR Corporation became a target of vandalism after protesters had accused the railway operator of kowtowing to pressure by Chinese media,[297] Protestors also demanded the release of CCTV footage from the 2019 Prince Edward station incident amid fears that police may have beaten someone to death.[298] Protesters also disrupted traffic by setting up roadblocks,[299][300] damaging traffic lights,[301] deflating the tires of buses,[302] and throwing objects onto railway tracks.[303] Protesters occasionally intimidated and assaulted mainlanders.[304]

Some radical protesters promoted the idea of "mutual destruction" or "phoenixism", these terms being translations of the Cantonese lam chau. They theorised that sanctions against the ruling CCP and the loss of Hong Kong's international finance centre and special trade status (caused by China's interference of the one-country, two systems principle) would destabilise mainland China's economy, and therefore, undermine the rule of the CCP and give Hong Kong a chance to be "reborn" in the future.[305][306] They believed that further government crackdown would ultimately speed up the process of lam chau, ultimately hurting the regime.[307]

Online confrontations

Doxing and cyberbullying

Doxing and cyberbullying were tactics used by both supporters and opponents of the protests. Some protesters used these tactics on police officers and their families and uploaded their personal information online.[308] By early July 2019, an estimated 1,000 officers' personal details had been reportedly leaked online, and nine individuals had been arrested. Affected officers, their friends and families were subject to death threats and intimidation.[309] By early June 2020, the number of officers doxed on social media was estimated at 1,752.[310] HK Leaks, an anonymous website based in Russia, and promoted by groups linked to the CCP, doxed about 200 people seen as being supportive of the protests. An Apple Daily reporter who was doxed by the website was targeted with sexual harassment via "hundreds of threatening calls".[311] University student leaders also received death threats.[312] Protest leaders have been attacked after being doxed.[313] According to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data, as of 30 August 2019, the proportion of doxing cases involving police officers comprised 59% of all reported and discovered cases. The remaining 41% of doxing cases involved other people such as protesters, those holding different political views, citizens and their family members.[314] No arrests have been made for doxing protesters.[315]

On 25 October 2019, Hong Kong Police obtained a court injunction prohibiting anyone from sharing any personal information about police officers or their families.[316] The ban was criticised for the possibility of producing a chilling effect on free speech; it was also criticised for having an excessively broad scope.[317][318] Cheng Lai-king, the chairwoman of the Central and Western District Council, was arrested for sedition after she shared a Facebook post which contains the personal information of a policeman who allegedly blinded the eye of an Indonesian journalist. The arrest was controversial as the sedition law was established during the colonial era and was rarely used.[319]

Spread of misinformation and propaganda

Both sides of the protests spread unverified rumours, misinformation and disinformation, which caused heightened reactions and polarisation among the public. This included tactics such as using selective cuts of news footage and creating false narratives.[320][321][322][323] Following the Prince Edward station incident, pro-democracy protesters laid down white flowers outside the station's exit to mourn the "deceased" for weeks after rumours circulated on the internet alleging that the police had beaten people to death during the operation.[324] The police, fire service, hospital authority and the government all denied the accusation.[325] Several deaths, most notably, that of Chan Yin-lam, a 15-year-old girl whom the police suspected had committed suicide, were the subject of a conspiracy theory given the unusual circumstances surrounding her death.[326] Rumours that female protesters were offering "free sex" to their male counterparts were repeated by a senior government member.[327] Another rumour was that the CIA was involved in instigating the protests after photographs of Caucasian men taking part in the protests were shared online.[328] Pro-Beijing camp also claimed pro-democracy lawmaker Lam Cheuk-ting was responsible for bringing protestors to Yuen Long causing the attack to occur, despite the fact that Lam himself was a victim of the attack and arrived after the attack began.[329] The police blamed fake news for causing public's distrust towards law enforcement,[330] though the police itself were also accused by several media outlets and prosecutors of lying to the public.[331][332]

The China government launched another misinformation campaign to malign and divide the protestors. The government used around 900 Twitter handles and five Facebook pages having a total follower of 15000 members to spread misinformation about the identity of the protestors. These social media accounts shared posts that called protestors members of ISIS. Twitter officials reportedly said these handles were part of larger network of 200,000 Twitter handles which they had to block.[333]

On 19 August 2019, both Twitter and Facebook announced that they had discovered what they described as large-scale disinformation campaigns operating on their social networks.[334][335] Facebook found posts which included images that were altered or taken out of context, often with captions intended to vilify and discredit the protesters.[336] According to investigations by Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, some attacks were coordinated, state-backed operations that were believed to have been carried out by agents of the Chinese government.[337] A report by the ASPI found that the purported disinformation campaign promoted three main narratives: condemnation of the protesters, support for the Hong Kong Police, and "conspiracy theories about Western involvement in the protests."[338] Google, Facebook, and Twitter banned these accounts. In a Facebook post, the Hong Kong edition of state-run China Daily suggested the protesters would launch a terrorist attack on 11 September 2019, producing as sole evidence a screenshot which it claimed to be from a group chat message on Telegram.[339]

Cyberattacks

On 13 June 2019, allegations of organised cyberattacks were made against the Chinese government. Pavel Durov, the founder of Telegram, suggested that the Chinese government may be behind the DDoS attacks on Telegram. On Twitter, Durov called the attack a "state actor-sized DDoS" because the attacks were mainly from IP addresses located in China. Additionally, Durov further tweeted that some of the DDoS attacks coincided with the protest on 12 June 2019.[340] Anonymous LIHKG moderators also suggested that the DDoS attack they experienced on 31 August 2019 were "unprecedented" and that they have "reasons to believe that there is a power, or even a national level power behind... such attacks." The forum identified two Chinese websites as being among those involved in the attack, including Baidu Tieba.[341]

Police misconduct

| External video | |

|---|---|

According to polls conducted by the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, net approval of the Hong Kong Police Force fell to 22 per cent in mid-2019, due to its handling of the protests.[342] At the end of July, 60 per cent of respondents in public surveys were dissatisfied with police handling of incidents since June 2019.[343] Nearly 70 per cent of Hong Kong citizens believe the police have acted unprofessionally by making indiscriminate arrests and losing self-control.[344] Their role and actions have raised questions about their accountability, the manner in which they wielded their physical force, and their crowd control methods. There have also been allegations of lack of consistency of law enforcement whether through deliberate inaction or poor organisation.

Inappropriate use of force

Hong Kong police were accused of using excessive and disproportionate force and not following both international safety guidelines and internal protocols while using their weapons.[345][69] According to Amnesty International, police aimed horizontally while firing, targeting protestors' heads and torsos.[69][132] Police use of bean bag rounds and rubber bullets allegedly ruptured the eyes of several protesters and the eye of an Indonesian journalist.[346][347][348] Police were found to have been using tear gas as an offensive weapon,[349] firing it indoors inside a railway station,[349] using expired tear gas, which could release toxic gases upon combustion,[350] and firing canisters from high-rise buildings.[351] Between June and November 2019, approximately 10,000 volleys of gas had been fired.[352] Chemical residues were found on different public facilities in various neighbourhoods.[353][354][lower-alpha 3] The use of tear gas sparked public health concerns after a reporter was diagnosed with chloracne in November 2019,[356] though both the environment department and the health department disputed these claims.[357]

Several police operations, in particular in Prince Edward station where the Special Tactical Squad (STS) assaulted commuters on a train, were thought by protesters and pro-democrats to have disregarded public safety.[358][359] Police were accused of using disproportionate force[360] after an officer shot two young protesters with live ammunition in Tsuen Wan and Sai Wan Ho on 1 October 2019 and 11 November 2019 respectively.[lower-alpha 4][366][367] An off-duty officer accidentally shot and injured a 15-year-old boy in Yuen Long on 4 October 2019 when he was assaulted by protesters who accused him of bumping into people with his car.[368] The siege of PolyU, which was described as a "humanitarian crisis" by democrats and medics,[369][137] prompted the Red Cross and Medecins Sans Frontieres to intervene as the wounded protesters trapped inside ran out of supplies and lacked first-aid care.[137]

Police were accused of obstructing first-aid service and emergency services[370][358][126] and interfering with the work of medical personnel inside hospitals.[371][372] The arrest of volunteer medics during the siege of PolyU was condemned by medical professionals.[373] Police were accused of using excessive force on already subdued, compliant arrestees. Videos showed the police kicking an arrestee,[374] pressing one's face against the ground,[375] using one as a human shield,[376] stomping on a demonstrator's head,[377] and pinning a protester's neck to the ground with a knee.[378] Video footage also shows the police beating passers-by, pushing and kicking people who were attempting to mediate the conflict,[379][380] and tackling minors and pregnant women.[381]

Protesters reported suffering brain haemorrhage and bone fractures after being violently arrested by the police.[382][383] Amnesty International stated that police had used "retaliatory violence" against protesters and mistreated and tortured some detainees. Detainees reported being forced to inhale tear gas, and being beaten and threatened by officers. Police officers shined laser lights directly into one detainee's eyes.[384][385][386][387] The police were accused of using sexual violence on female protesters.[388] A female alleged that she was gang raped inside Tsuen Wan police station, while the police reported that their investigation did not align with her accusation,[389] and later announced plans to arrest her on suspicion of providing false information.[390] Some detainees reported police had denied them access to lawyers and delayed their access to medical services.[386][391] Many of these allegations were believed to have taken place in San Uk Ling Holding Centre.[392]

Questionable tactics and unprofessional behaviour

The kettling of protesters,[359][393] police operations on private property,[394] the firing of pepper ball rounds at protesters at near point-blank range,[395] the dyeing of Kowloon Mosque, the use of the water cannon trucks against pedestrians,[345][396] insufficient protection for police dogs,[397] accessing patients' medical records without consent,[398][399][400] driving dangerously, and how police displayed their warning signs[401] were also sources of controversy. A police officer was suspended after he hit one protester with a motorcycle and dragged him on 11 November 2019.[402][403] He was later reinstated.[404] A police van suddenly accelerated into a crowd of protesters, causing a stampede as STS officers exiting from the van chased protesters in Yau Ma Tei on 18 November 2019. Police defended the latter action as an appropriate response by well-trained officers to attacks by protesters, and that "[driving] fast doesn't mean it is unsafe".[405]

Some police officers wore face masks,[406] did not wear uniforms with identification numbers or failed to display their warrant cards,[407][408] making it difficult for citizens to file complaints. The government explained in June 2019 that there was not enough space on the uniforms to accommodate identification numbers. In June 2020, the appearance of various decorations on uniforms caused this explanation to be doubted.[409] The court ruled in November 2020 that the police had breached the Hong Kong Bill of Rights Ordinance by hiding or not displaying their identification number.[410] In late 2019 the government introduced "call signs" to replace warrant cards, but it was found that officers shared call signs.[411]

The police has also repeatedly interfered with the justice process. It has been suspected of tampering with evidence,[412][413][414] giving false testimony before court,[415] and coercing false confessions from arrestees.[416] The deployment of undercover officers who were suspected of committing arson and vandalism also generated controversy, and the ability of police officers to identify the differences between ordinary protesters and undercover officers was questioned.[417][418] A police officer was arrested in April 2020 for perverting the course of justice after he allegedly instructed a teen to throw petrol bombs at a police station he works at.[lower-alpha 5][419]

Some uniformed officers used foul language to harass and humiliate protesters and journalists[420] and provoked protesters.[421] The slur "cockroach"—whose dehumanising qualities have been recognised in the social sciences and psychology—was used frequently by frontline officers to insult protesters; some officers sought to counter this development,[422] and suggested that in several instances, verbal abuse by protesters may have led officers to use the term.[423] An officer was reprimanded by his superiors for shouting derisive comments to protesters about the death of Chow Tsz-lok.[424] Police described a man wearing a yellow vest who was taken to an alley, surrounded by police officers, and apparently physically abused by one of them, as a "yellow object". Their claim that it was impossible to recognise a person in the video footage was widely criticised.[425]

Lack of consistency

Police were also accused of spreading a climate of fear[426] by conducting hospital arrests,[427][428] attacking protestors while undercover,[382][429] arresting people arbitrarily,[430] targeting youngsters,[431][384] banning requests for demonstrations,[432] and arresting high-profile activists and lawmakers.[433] During the pandemic period, it has also used the law banning groups of 4 to further ban peaceful protests. They were also accused of abusing the law by issuing fines to civilians who show up in protest scenes.[434]

However, the police were accused of applying double standards by showing leniency towards violent counter-protesters.[435] It has also failed to fulfill its duty to protect the protesters as well. Their slow response and inaction during the Yuen Long attack sparked accusations they had colluded with the attackers.[16][436] Lawyers pointed out that police inaction, such as shutting the gates of the nearby police stations during the Yuen Long attacks might constitute misconduct in public office,[437] [421][16] while the IPCC reported that the jamming of the emergency hotline during the attack was also a common criticism.[438] Shop owners in Yuen Long have expressed concern after police failed to consult them for evidence even six months after the attack.[439]

Lack of accountability

Police modified the Police General Orders by removing the sentence "officers will be accountable for their own actions" ahead of the 1 October 2019 confrontation. Police sources of the Washington Post have said that a culture of impunity pervades the police force, such that riot police often disregarded their training or became dishonest in official reports to justify excessive force.[345] Police officers who felt that their actions were not justified were marginalised.[440] Police commanders reportedly ignored the wrongdoings and the unlawful behaviours of frontline riot police and refused to use any disciplinary measures to avoid upsetting them.[345] Lam's administration also denied police wrongdoings and backed the police multiple times.[441] As of December 2019, no officer had been suspended for their actions or charged or prosecuted over protest-related actions.[345] When the District Councils were passing motions to condemn police violence, police commissioner Chris Tang and other civil servants walked out in protest.[442]

The Independent Police Complaints Council (IPCC) launched investigations into alleged incidents of police misconduct during the protests. Protesters demanded an independent commission of inquiry instead, as the members of the IPCC are mainly pro-establishment and it lacks the power to investigate, make definitive judgements, and hand out penalties.[443][444][109] Despite calls from both local[445] and international opinion leaders, Carrie Lam and both police commissioners Stephen Lo and Chris Tang rejected the formation of an independent committee.[446] Lam insisted that the IPCC was able to fulfill the task,[447] while Tang called the formation of such a committee an "injustice" and a "tool for inciting hatred" against the force.[345]

On 8 November 2019, a five-member expert panel headed by Sir Denis O'Connor and appointed by Lam in September 2019 to advise the IPCC, concluded that the police watchdog lacked the "powers, capacity and independent investigative capability necessary" to fulfill its role as a police watchdog group and suggested the formation of an independent commission of inquiry given the current protest situation.[448] After negotiations to increase the IPCC's powers fell through, the five panel members quit on 11 December 2019.[449] The IPCC report on police behaviour during the protests released in May 2020 concluded that police has mostly followed the guidelines though there was room for improvement.[450] While government officials called the report "comprehensive", democrats and human rights organisations were unanimous in declaring it a whitewash of police misdeeds.[451] One of the expert panel members, Clifford Stott, said in June 2020 that the police had misjudged the dynamics of the protests and had used disproportionate force at almost all protests, thus creating more disorder than it prevented.[452] A report co-authored by Stott, published in November 2020, saw the "absence of any credible system of accountability for the police" as one major reason for why the protests became more radical.[453]

Local media coverage

.jpg.webp)

The protests received significant press attention. Nathan Ruser from ASPI identified the protests as the most live-streamed social unrest in history. According to a poll conducted by CUHK, live feeds have replaced traditional media, social media and Telegram as the main way for citizens of Hong Kong to access protest-related information. Ruser suggested that unlike other protests, the widespread use of livestreaming technology in the Hong Kong protests meant that there was "almost parity when it comes to what [one] can learn remotely researching it to actually being there".[455]

Many of Hong Kong's media outlets are owned by local tycoons who have significant business ties in the mainland, so many of them adopt self-censorship at some level and have mostly maintained a conservative editorial line in their coverage of the protests. The management of some firms have forced journalists to change their headline to sound less sympathetic to the protest movement.[456] A report by BBC suggested that the management of local terrestrial broadcaster Television Broadcasts Limited (TVB) had forced employees to include more voices supporting the government and highlight the aggressive actions of the protesters, without including segments focusing on the responses from the protesters or the democrats.[457] Journalists from South China Morning Post, which was acquired by the Chinese Alibaba Group in 2016, had their news pieces significantly altered by senior editors to include a pro-government viewpoint before they were published.[458] TVB and local news outlet HK01 were accused of pro-government bias, and protesters have physically assaulted their news crews and damaged their equipment and vehicles.[459][460] Protesters also placed political pressure on various corporations, urging them to stop placing advertisements on TVB.[461]

On the other hand, Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK), a public broadcasting service, faced criticisms of bias in favour of the protest movement. Its critics have surrounded the headquarters of RTHK and assaulted its reporters.[462] RTHK also faced political pressure from the police directly: police commissioner Chris Tang filed complaints to RTHK against the satirical TV show Headliner and opinion program Pentaprism for "insulting the police" and "spreading hate speech" respectively.[lower-alpha 6] The police were criticised by journalists and democrats for interfering with press freedom.[465] In response to around 200 complaints received by the Communications Authority, RTHK apologised "to any police officers or others who have been offended" and cancelled Headliner in May 2020, ending its 21-year run.[466] RTHK journalist Nabela Qoser, known for her blunt questioning of government officials at press conferences, was subjected to racist abuse online by pro-Beijing groups, prompting a statement of "grave concern" from the Equal Opportunities Commission.[467][468] She also had her probation period at RTHK extended.[469]

Journalists have experienced interference and obstruction from the police in their reporting activities.[470] Police frequently used flashlights against reporters, shining light at cameras to avoid them being filmed or photographed; journalists also reported frequently being harassed, searched,[454][471][472] and insulted. In some cases, despite identifying themselves, they were jostled, subdued, pepper-sprayed, or violently detained by the police.[473][474][475][476] Several female reporters complained about being sexually harassed by police officers.[471] Journalists were also caught in the crossfire of protests:[477][478] Indonesian journalist Veby Mega Indah of Suara was blinded by a rubber bullet;[479] a reporter from RTHK suffered burns after he was hit by a petrol bomb.[480] Student journalists have also been targeted and attacked by police.[481]

Police raided the headquarters of pro-democratic newspaper Apple Daily and searched its editorial and reporters' areas on 10 August 2020. During the operation, reporters from several major news outlets were rejected from entering cordoned-off areas where a scheduled press briefing was held. Police stated that media who were "unprofessional", or had been reporting in the past in a manner considered by police as biased against the force, would be denied access to such briefings in the future.[482][483] In September 2020, the police further limited press freedom by narrowing the definition of "media representatives", meaning that student reporters and freelancers would have to face more risks when they are reporting.[484]

Hong Kong's fall by seven places to 80th in the World Press Freedom Index was attributed by Reporters without Borders to the policy of violence against journalists. When the Press Freedom Index was established in 2002, Hong Kong had ranked 18th.[485] Following the passing of the national security law, The New York Times announced that it would relocate its digital team's office to Seoul, as the law has "unsettled news organisations and created uncertainty about the city's prospects as a hub for journalism in Asia".[486] The Immigration Department also started declining work visas for foreign journalists, including those working for New York Times and local outlet Hong Kong Free Press.[487]

Impact

Economy

.jpg.webp)

Official statistics showed that Hong Kong had slipped into recession as its economy had shrunk in the second and third quarters of 2019.[488] Retail sales declined and consumer spending decreased.[489] Some restaurants saw their customers cancel bookings, and certain banks and shops were forced to close their doors. Some supply chains were disrupted because of the protests. Lower consumer spending caused several luxury brands to delay shop openings, while other brands quit.[490] While some hawkers protested about declining sales,[491] some shops prospered as nearby protesters bought food and other commodities.[492] Stock of protest supplies ran low in both Hong Kong and Taiwan.[493]

The protests also affected property owners: Fearing the instability, some investors abandoned the purchases of land. Demand for property also declined, as overall property transactions dropped by 24 per cent when compared with the Umbrella Revolution; Property developers were forced to slash prices.[494] Trade shows reported decreased attendance and revenue, and many firms cancelled their events in Hong Kong.[495] The Hang Seng Index declined by at least 4.8 per cent from 9 June 2019 to late August 2019. As investment sentiment waned, companies awaiting listing on the stock market put their initial public offerings (IPO) on hold, there being only one in August 2019 – the lowest since 2012. Fitch Ratings downgraded Hong Kong's sovereignty rating from AA+ to AA due to doubts over the government's ability to maintain the "one country, two systems" principle; the outlook on the territory was similarly downgraded from "stable" to "negative".[496]

Tourism was also affected: the number of visitors travelling to Hong Kong in August 2019 declined by 40 per cent compared to a year earlier,[497] while the National Day holiday saw a decline of 31.9 per cent.[498] Unemployment increased from 0.1 per cent to 3.2 per cent from September to November 2019, with the tourist and the catering sectors, seeing rises to 5.2 per cent and 6.2 per cent respectively during the same period, being the hardest hit.[499] Flight bookings also declined, with airlines cutting or reducing services.[500] During the airport protests on 12 and 13 August 2019, the Airport Authority cancelled numerous flights, which resulted in an estimated US$76 million loss according to aviation experts.[501] Various countries issued travel warnings to their citizens concerning Hong Kong, and many mainland Chinese tourists avoided travelling to Hong Kong due to safety concerns.[502]

The economy in Hong Kong became increasingly politicised. Some corporations bowed to pressure and fired employees who expressed their support for the protests.[504][505] Several international corporations and businesses including the National Basketball Association and Activision Blizzard decided to appease China during the protests and faced intense criticisms.[506] The Diplomat called the Yellow Economic Circle "one of the most radical, progressive, and innovative forms of long-term struggle" during the protests.[507] Corporations perceived to be pro-Beijing faced boycotts, and some were vandalised.[508] Meanwhile, "yellow" shops allied with protesters enjoyed a flurry of patrons even during the coronavirus crisis.[509]

Governance

Lam's administration was criticised for its performance during the protests – her perceived arrogance and obstinacy,[510][48] and her reluctance to engage in dialogue with protesters. Her extended absences, stonewalling performance at press conferences,[511] were all believed to have enabled the protesters to escalate events.[512][lower-alpha 7] According to public opinion polls, Lam's approval rating plunged to 22.3 in October 2019, the lowest among all chief executives. Her performance and those of Secretary for Security John Lee and Secretary for Justice Teresa Cheng were called "disastrous".[514] On 2 September, Reuters received a leaked audio recording in which Carrie Lam admitted that she had "very limited" room to manoeuvre between the Central People's Government and Hong Kong, and that she would quit, if she had a choice.[515] However, the next day she told the media that she had never contemplated discussing her resignation with the Beijing authorities.[516] Lam's behaviour on this and later occasions strengthened the perception among a broad part of the protesters and their supporters that she was not able to make any crucial decision without instructions from the Beijing government, effectively serving as its puppet.[517] Distrust toward the government and the lack of police accountability also led to the temporary prevalence of conspiracy theories.[417]

Both sides claimed that rule of law in Hong Kong was undermined during the protests. While the government, the police and government supporters criticised the protesters for breaking the law and using violence to "extort" the government to accept the demands, the protesters and their sympathisers felt that lack of police oversight, selective law enforcement, selective prosecution, police brutality, and the government's blanket denial of all police wrongdoings all harmed rule of law and expressed their disappointment that the law cannot help them achieve justice.[518] The judiciary was also scrutinised after judge Kwok Wai-kin expressed sympathy to a stabber who attacked three people in September 2019 near a Lennon Wall. He was later removed from handling all protest-related cases.[519]

The government's extended absence and its lack of a political solution in the early stage of the protests catapulted the police into the front line, and heavy-handed policing became a substitute for solving a political crisis.[520] The police force was initially "lost and confused" and was discontent with the government for not offering enough support.[521] Subsequently, Lam's blanket denial of allegations of police brutality led to accusations that Lam and her administration endorsed police violence.[441] Throughout the protests, the establishment waited for demonstrators' aggression to increase so they could justify greater militarisation of the police and dismiss the protesters as "insurgents" and thereby also dismiss their demands.[522] Ma Ngok, a political scientist, remarked that the failures of the government meant that it "has lost the trust of a whole generation" and predicted that youths would remain angry at both the government and the police for years to come.[523]

Police's image and accountability

The reputation of the police took a serious drubbing following the heavy-handed treatment of protesters.[524][525][526] In October 2019, a survey conducted by CUHK revealed that more than 50 per cent of respondents were deeply dissatisfied with the police's performance.[527] According to some reports, their aggressive behaviours and tactics have caused them to become a symbol that represents hostility and suppression. Their actions against protesters resulted in a breakdown of citizens' trust of the police.[528][529] Citizens were also concerned over the ability of the police to regulate and control their members and feared their abuse of power.[530] The suspected acts of police brutality led some politically neutral or political apathetic citizens to become more sympathetic towards the young protesters.[531] Fearing Hong Kong was changing into a police state, some citizens actively considered emigration.[532] The lack of any prosecutions against officers, and the absence of independent police oversight, sparked fears that the police could not be held accountable for their actions and that they were immune to any legal consequences.[345]

Affected by the controversies surrounding the police force's handling of the protests, between June 2019 to February 2020, 446 police officers quit (which was 40 per cent higher than the figure in 2018), and the force only managed to recruit 760 officers (40 per cent lower than the previous year), falling well short of the police force's expectations.[533] The police cancelled foot patrols because of fears officers may be attacked,[534] and issued extendable batons to off-duty officers.[530] Police officers also reported being "physically and mentally" tired, as they faced the risks of being doxed, cyberbullied, and distanced by their family members.[535] Police relations with journalists,[536] social workers,[537][538] medical professionals[539] and members from other disciplined forces[540] became strained.

Society

The protests deepened the rift between the "yellow" (pro-democracy) and "blue" (pro-government) camps created since the Umbrella Revolution. People who opposed the protests argued that protesters were spreading "chaos and fear" across the city, causing damage to the economy and thus harming people not involved in the protests. On the other hand, protesters justified their actions by what they saw as the greater good of protecting the territory's freedoms against the encroachment of mainland China.[541] Anti-mainland sentiments swelled during this period.[542] Family relationships were strained, as children argued with their parents over their attending protests, either because they felt that the protests reflected outdated values, or they disagreed with their parent's political stance or the manner of the protests.[543]

As the protests continued to escalate, citizens showed an increasing tolerance towards confrontational and violent actions.[544] Pollsters found that among 8,000 respondents, 90% of them believed that the use of these tactics was understandable because of the government's refusal to respond to the demands.[545] The protest movement provided a basis for challenging the government over its controversial handling of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020,[148] and some observers ascribed the success in halting the first wave of the pandemic to protesters' related efforts.[546] Unity among the protesters was seen across a wide spectrum of age groups and professions.[lower-alpha 8] While some moderate protesters reported that the increase in violence alienated them from the protests,[541] public opinion polls conducted by CUHK suggested that the movement was able to maintain public support.[527] The unity among protesters fostered a new sense of identity and community in Hong Kong, which had always been a very materialistic society. This was evidenced by the adoption of "Glory to Hong Kong" as a protest anthem.[38]