Women in Love (film)

Women in Love is a 1969 British romantic drama film directed by Ken Russell and starring Alan Bates, Oliver Reed, Glenda Jackson, and Jennie Linden. The film was adapted by Larry Kramer from D. H. Lawrence's 1920 novel Women in Love.[2] It is the first film to be released by Brandywine Productions.[3]

| Women in Love | |

|---|---|

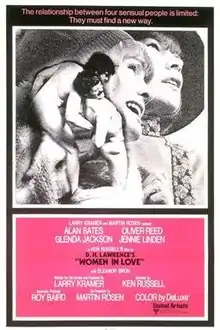

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ken Russell |

| Produced by | Larry Kramer |

| Screenplay by | Larry Kramer |

| Based on | Women in Love by D. H. Lawrence |

| Starring | Alan Bates Oliver Reed Glenda Jackson Jennie Linden Eleanor Bron |

| Music by | Georges Delerue Michael Garrett |

| Cinematography | Billy Williams |

| Edited by | Michael Bradsell |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 131 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.6 million[1] |

| Box office | $4.5 million (Worldwide)[1] |

The plot follows the relationships between two sisters and two men in a mining town in post-World War I England.[4] The two couples take markedly different directions. The film explores the nature of commitment and love.

The film was nominated for four Academy Awards, with Jackson winning the Academy Award for Best Actress for her role, and the film receiving other honours.

Plot

The film takes place in 1920, in the Midlands mining town of Beldover. Two sisters, Ursula and Gudrun Brangwen, discuss marriage on their way to the wedding of Laura Crich, daughter of the town's wealthy mine owner, Thomas Crich, to Tibby Lupton, a naval officer. At the village's church, each sister is fascinated by a particular member of the wedding party – Gudrun by Laura's brother, Gerald, and Ursula by Gerald's best friend, Rupert Birkin. Ursula is a school teacher and Rupert is a school inspector; she remembers his visit to her classroom, interrupting her botany lesson to discourse on the sexual nature of the catkin.

The four are later brought together at a house party at the estate of Hermione Roddice, a rich woman whose relationship with Rupert is falling apart. When Hermione devises, as entertainment for her guests, a dance in the "style of the Russian ballet", Rupert becomes impatient with her pretensions and tells the pianist to play some ragtime. This sets off spontaneous dancing among the whole group and angers Hermione. She leaves. When Rupert follows her into the next room, she smashes a glass paperweight against his head, and he staggers outside. He discards his clothes and wanders through the woods. Later, at the Criches' annual picnic, to which most of the town is invited, Ursula and Gudrun find a secluded spot, and Gudrun dances before some Highland cattle while Ursula sings "I'm Forever Blowing Bubbles". When Gerald and Rupert appear, Gerald calls Gudrun's behaviour "impossible and ridiculous", and then says he loves her. "That's one way of putting it", she replies. Ursula and Rupert wander away discussing death and love. They make love in the woods. The day ends in tragedy when Laura and Tibby drown while swimming in the lake.

During one of Gerald and Rupert's discussions, Rupert suggests Japanese-style wrestling. They strip and wrestle in the firelight. Rupert enjoys their closeness and says they should swear to love each other, but Gerald cannot understand Rupert's idea of wanting to have an emotional union with a man as well as an emotional and physical union with a woman. Ursula and Rupert decide to marry while Gudrun and Gerald continue to see each other. One evening, emotionally exhausted after his father's illness and death, Gerald sneaks into the Brangwen house to spend the night with Gudrun in her bed, then leaves at dawn.

Later, after Ursula and Rupert's marriage, Gerald suggests that the four of them go to the Alps for Christmas. At their inn in the Alps, Gudrun irritates Gerald with her interest in Loerke, a gay German sculptor. An artist herself, Gudrun is fascinated with Loerke's idea that brutality is necessary to create art. While Gerald grows increasingly jealous and angry, Gudrun only derides and ridicules him. Finally, he can endure it no longer. After attempting to strangle her, he trudges off into the cold, to commit suicide and die alone. Rupert and Ursula return to their cottage in England. Rupert grieves for his dead friend. As Ursula and Rupert discuss love, Ursula says there can't be two kinds of love. He explains that she is enough for love of a woman but there is another eternal love and bond for a man.

Cast

- Alan Bates as Rupert Birkin

- Oliver Reed as Gerald Crich

- Glenda Jackson as Gudrun Brangwen

- Jennie Linden as Ursula Brangwen

- Eleanor Bron as Hermione Roddice

- Alan Webb as Thomas Crich

- Vladek Sheybal as Loerke

- Catherine Willmer as Mrs. Christianna Crich

- Phoebe Nicholls as Winifred Crich

- Sharon Gurney as Laura Crich

- Christopher Gable as Tibby Lupton

- Michael Gough as Mr. Tom Brangwen

- Norma Shebbeare as Mrs. Brangwen

- Nike Arrighi as Contessa

- James Laurenson as Minister

- Michael Graham Cox as Palmer

- Richard Heffer as Loerke's friend

- Michael Garratt as Maestro

Production

Development

Larry Kramer was an American who moved to London in 1961 to work as an assistant story editor at Columbia and had become an assistant to David Picker at United Artists.[5] United Artists wanted Kramer to move to New York but he wanted to live in London and produce, so he quit his job. He went to work on 1967's Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush as producer and ended up rewriting the script.

He was looking for another project when Silvio Narizzano, who had directed the successful Georgy Girl (1966), suggested Kramer make a film of Women in Love. Kramer read the novel, loved it, and optioned the screen rights for $4,200. He wrote a screen treatment based on the chapters and succeeded in selling the project to David Chasman and David Picker at United Artists.[5][6]

Script

Kramer originally commissioned a screenplay from David Mercer. Mercer's adaptation differed too much from the original book and he was bought out of the project. "It was a horrible Marxist tract," Kramer said. "Just horrible. I had no script and no more money for another writer.[6]

Ultimately, Kramer wrote the script, although he had not written one before. "I became a writer not by choice but out of necessity," he said.[7]

Kramer said "slightly more than half the film" was directly from the novel. He took the rest from various sources including Lawrence's letters, essays, poems and plays.[7]

"I wanted to show you can convey emotion along with action and that ideas and talk and beautiful scenery are not incompatible in films," said Kramer. "My first draft was all dialog, the second was mostly visual. The end result was a combination of both."[7]

Ken Russell

Narizzano, intended as director, left the project after suffering a series of personal setbacks. He divorced his wife for a man who died soon after. After Narizzano's departure, Kramer considered a number of directors to take on the project, including Jack Clayton, Stanley Kubrick and Peter Brook, all of whom declined.[6]

Ken Russell had previously directed only two films and was better known then for his biographical projects about artists for the BBC. His second film, Billion Dollar Brain was admired by Chasman and Picker at UA, who told him "they thought it got a raw deal from right wing critics and that I could do better with a more sympathetic subject."[8] Chasman and Picker sent a copy of Kramer's script to Russell, who liked it. The director read the novel, which he loved; he called Women in Love "probably the best English novel ever written."[9] He and Kramer collaborated on further drafts of the script, using information from Lawrence's own life and adding extra bits from the novel.[8] This included adding the nude wrestling scene. "It wasn’t in the original script," wrote Russell. "I didn't think it would pass the censor and I knew it would be difficult to shoot. I was wrong on my first guess and right on my second. Oily [Oliver Reed] talked me into it. He wrestled with me, jujitsu style, in my kitchen, and wouldn't let me up until I said, ‘OK, OK, you win, I’ll do it.’"[10]

By the time United Artists approved the script, the project had a second producer, Martin Rosen.[8]

Casting

Russell says casting was "difficult" in part because most of his television work was done with non-actors so he was "totally out of touch to the real talent at hand."[8]

Kramer had been talking to Alan Bates about playing Birkin for a number of years and he was cast relatively easily. Bates sported a beard, giving him a physical resemblance to D.H. Lawrence.[8]

Michael Caine who had just made Billion Dollar Brain with Russell says he was offered a lead role but turned it down because he felt unable to do the nude scene.[11]

Kramer wanted Edward Fox for the role of Gerald. Fox fitted Lawrence's description of the character ("blond, glacial and Nordic"), but United Artists, the studio financing the production, imposed Oliver Reed, a more bankable star, as Gerald even though he was not physically like Lawrence's description of the character. Russell had worked with Reed before and said even though the actor "wasn't ideal physically for the part he couldn't have played it better."[8]

Kramer was adamant to give the role of Gudrun to Glenda Jackson. She was, then, well recognised in theatrical circles. As a member of the Royal Shakespeare Company she had gained a great deal of attention as Charlotte Corday in Marat/Sade. United Artists was unconvinced, considering her not conventionally beautiful enough for the role of Gudrun, who drives Gerald to suicide. Russell was unimpressed when he met Jackson and says only in seeing Marat/Sade "did I realise what a magnificent screen personality she is."[8]

The last of the four main roles to be cast was that of Ursula. Both Vanessa Redgrave and Faye Dunaway declined to take the role, finding it the less interesting of the two sisters and that they would be easily eclipsed by Glenda Jackson's acting skills. It was by accident that Russell and Kramer came upon a screen test that Jennie Linden had made opposite Peter O'Toole for The Lion in Winter, for a part she did not get.[12] Linden had recently given birth to her only son and was not eager to take the role but was persuaded by Kramer and Russell.

Bates and Reed received a percentage of the profits while Linden and Jackson were paid a straight salary.[7]

The composer Michael Garrett who also contributed to the score can be seen playing the piano in one scene.

Shooting

Filming started 25 September 1968 and took place in north England and Switzerland.[13] The opening scene with credits was shot at what is now Crich Tramway Museum in Derbyshire. It took sixteen weeks and was budgeted at $1.65 million but came in at $1.5 million "because everyone was helpful," says Kramer, including key participants taking a percentage.[7][14] Jackson was pregnant during filming.[15]

The film features a famous nude wrestling scene between Bates and Reed. Kramer says Reed turned up to the shoot drunk and got Bates drunk.[7] "I had to get drunk before I exposed myself on camera," said Reed.[16]

Russell said he regretted omitting a scene where the sisters went to London "where they sample la vie boheme. It helped form their characters and explains their subsequent behaviour. And at least two of the actors were miscast. Another had to be replaced after his second appearance. But none of that matters when a movie turns you on. You can have brilliant camerawork, great editing, a fine script and good acting, but it don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing."[10]

Release and reception

Censor

The film was passed uncut by the British censor.[17]

Box office

The film was one of the eight most popular films at the British box office in 1970.[18] As it cost $1.6 million it recouped its costs in England alone.[5]

It made $3.0 million in rentals in the U.S. and Canada[19] and made $4.5 million worldwide.[1]

Russell later wrote "I’ve made better films than Women in Love but obviously it had something that tickled the public’s fancy, and it wasn’t just the male members of Messrs Bates and Reed. It might have probed intimacy between the sexes as few movies had before, but I can take scant credit for that. I was only putting on the screen what D.H. Lawrence had written half a century before. But the film did have some excellent performances...and both Alan and Olly really came to grips with the subject, especially in the nude wrestling scene."[10]

Critical response

Released in Britain in 1969 and the US in 1970, the film was applauded as a good rendering of D.H. Lawrence's once controversial novel about love, sex and the upper class in England. During the making of the film, Russell had to work on conveying sex and the sensual nature of Lawrence's book. Many of the stars came to understand this was to be a complex piece. Oliver Reed would do a nude wrestling scene with Alan Bates. He went as far as to persuade (and physically twist the arm of) director Russell to film the scene. Russell conceded and shot the controversial scene, which suggested the homoerotic undertones of Gerald and Rupert's friendship. The wrestling scene caused the film to be banned altogether in Turkey. Considered the best of Russell's films, it led him to adapt Lawrence's preceding novel The Rainbow into a 1989 film of the same name, followed by the 1993 BBC TV miniseries Lady Chatterley.

Women in Love received positive reviews from critics and currently holds an 83% rating on review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 23 reviews with an average rating of 7.5/10.[20] Film critic Emanuel Levy has said of the film: "Though deviating from D. H. Lawrence's novel considerably, this is Ken Russell's most fully realised narrative film, lavishly mounted and well-acted, especially by Glenda Jackson in an Oscar-winning performance."[21]

Accolades

Home media

Women in Love was released on VHS by MGM Home Entertainment in 1994, and on DVD in Regions 1 and 2 in 2003. The film was released on Blu-ray and DVD by the Criterion Collection on 27 March 2018, with the Blu-ray featuring a restored 4K digital transfer.[27][28] The supplementary materials on the Criterion release include audio commentaries and various interviews, along with the 1972 short film Second Best, produced by and starring Alan Bates, based on a story by D.H. Lawrence.[29][30]

See also

References

- Balio, Tino (1987). United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 246-247. ISBN 9780299114404. LCCN 87-040138.

- Canby, Vincent (26 March 1970). "Women in Love (1969)". NY Times. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- Slide, Anthony (18 January 2013). Fifty Classic British Films, 1932-1982: A Pictorial Record. Courier Corporation. p. 133. ISBN 9780486148519.

- Lawrence, Will (19 October 2007). "Viggo Mortensen: My painful decision to fight in the nude". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Larry Kramer: New Frontiersman of Film: Exploring Film's New Frontiers By Gary Arnold. The Washington Post, Times Herald 15 Apr 1970: C1.

- Public nuisance, Specter, Michael. The New Yorker; New York Vol. 78, Iss. 11, (May 13, 2002): 056.

- Kramer Scripts Thinking Man's 'Women in Love': Thinking Man's 'Women in Love', Warga, Wayne. Los Angeles Times 3 May 1970: c1.

- THE MAKING OF 'WOMEN IN LOVE The Observer 2 Sep 1973: 25.

- Ken Russell: A Director Who Respects Artists Kahan, Saul. Los Angeles Times 28 Mar 1971: n18.

- Russell, Ken. The Lion Roars.

- Hallfirst= William (2003). 70 not out : the biography of Sir Michael Caine. John Blake. p. 183.

- Russell p 62

- Lawrence with the charm turned off Hall, John. The Guardian 21 Oct 1968: 6.

- Sandles, Arthur (15 January 1970). "Finance tighter for the film industry". The Canberra Times. p. 14. Retrieved 30 March 2014 – via National Library of Australia.

- Glenda Jackson: Wife, Mother, Sex Goddess Evans, Peter. Los Angeles Times 28 Feb 1971: x14.

- Reed's Formula for Success Murphy, Mary B. Los Angeles Times 27 Mar 1971: a9.

- MISCELLANY: Crossed lines The Guardian 9 Oct 1969: 13.

- a Staff Reporter. "Paul Newman Britain's favourite star." Times [London, England] 31 December 1970: 9. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 11 July 2012.

- "Tracking the Players". Variety. Penske Business Media, LLC.: 36. 18 January 1993.

- "Women in Love (1969)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Levy, Emanuel. "Women in Love (1970): Forty Years Ago..." Emanuel Levy. Archived from the original on 13 December 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- "The 43rd Academy Awards | 1971". Academy Awards. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Film in 1970". British Academy Film Awards. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Women in Love". Golden Globe Awards. Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "1970 Award Winners". National Board of Review Awards 1970. National Board of Review. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Jane, Ian (26 March 2018). "Women in Love (Blu-ray)". DVD Talk. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "Women in Love - The Criterion Collection". Amazon. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- "Women in Love (1969)". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Barta, Preston (23 March 2018). "DVD reviews: 'Last Jedi' unleashes a tour de force for home entertainment". The Denton Record-Chronicle. Denton Publishing. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

Bibliography

- Powell, Dilys (1989) The Golden Screen. London: Pavilion; pp 244–45

- Russell, Ken (1991). Altered states. Bantam Books.

- Taylor, John Russell (1969) Review in The Times 13 November 1969

External links

- Women in Love at IMDb

- Women in Love at Letterbox DVD

- Women in Love at Rotten Tomatoes

- Women in Love at Virtual History

- Women in Love: Bohemian Rhapsody an essay by Linda Ruth Williams at the Criterion Collection