Wood engraving

Wood engraving is a printmaking technique, in which an artist works an image or matrix of images into a block of wood. Functionally a variety of woodcut, it uses relief printing, where the artist applies ink to the face of the block and prints using relatively low pressure. By contrast, ordinary engraving, like etching, uses a metal plate for the matrix, and is printed by the intaglio method, where the ink fills the valleys, the removed areas. As a result, wood engravings deteriorate less quickly than copper-plate engravings, and have a distinctive white-on-black character.

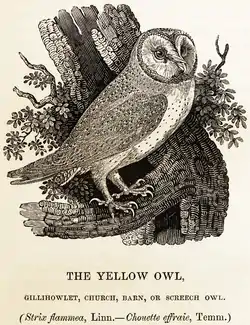

Thomas Bewick developed the wood engraving technique in Great Britain at the end of the 18th century.[1] His work differed from earlier woodcuts in two key ways. First, rather than using woodcarving tools such as knives, Bewick used an engraver's burin (graver). With this, he could create thin delicate lines, often creating large dark areas in the composition. Second, wood engraving traditionally uses the wood's end grain—while the older technique used the softer side grain. The resulting increased hardness and durability facilitated more detailed images.

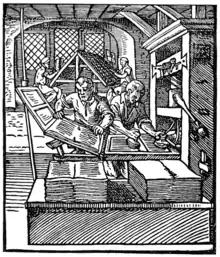

Wood-engraved blocks could be used on conventional printing presses, which were going through rapid mechanical improvements during the first quarter of the 19th century. The blocks were made the same height as, and composited alongside, movable type in page layouts—so printers could produce thousands of copies of illustrated pages with almost no deterioration. The combination of this new wood engraving method and mechanized printing drove a rapid expansion of illustrations in the 19th century. Further, advances in stereotype let wood-engravings be reproduced onto metal, where they could be mass-produced for sale to printers.

By the mid-19th century, many wood engravings rivaled copperplate engravings.[2] Wood engraving was used to great effect by 19th-century artists such as Edward Calvert, and its heyday lasted until the early and mid-20th century when remarkable achievements were made by Eric Gill, Eric Ravilious, Tirzah Garwood and others. Though less used now, the technique is still prized in the early 21st century as a high-quality specialist technique of book illustration, and is promoted, for example, by the Society of Wood Engravers, who hold an annual exhibition in London and other British venues.

History

In 15th- and 16th-century Europe, woodcuts were a common technique in printmaking and printing, yet their use as an artistic medium began to decline in the 17th century. They were still made for basic printing press work such as newspapers or almanacs. These required simple blocks that printed in relief with the text—rather than the elaborate intaglio forms in book illustrations and artistic printmaking at the time, in which type and illustrations were printed with separate plates and techniques.

The beginnings of modern wood engraving techniques developed at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century, with the works of Englishman Thomas Bewick. Bewick generally engraved harder woods, such as boxwood, rather than the woods used in woodcuts, and he engraved the ends of blocks instead of the side.[2] Finding a woodcutting knife not suitable for working against the grain in harder woods, Bewick used a burin (or graver), an engraving tool with a V-shaped cutting tip.[2] As Thomas Balston explains, Bewick abandoned the attempts of previous wood-engravers 'to imitate the black lines of copper engravings. Though not, as frequently asserted, the inventor of wood-engraving, he was the first to recognise that, as the incisions made by the graver on the wood block printed white, the right use of the medium was to base his designs as much as possible on white lines and areas, and so he became the first to use his graver as a drawing instrument and to employ the medium as an original art.‘[3] From the beginning of the nineteenth century Bewick's techniques gradually came into wider use, especially in Britain and the United States.

Alexander Anderson introduced the technique to the United States. Bewick's work impressed him, so he reverse engineered and imitated Bewick's technique—using metal until he learned that Bewick used wood.[4] There it was further expanded upon by his students, Joseph Alexander Adams.

Growth of illustrated publications

Besides interpreting details of light and shade, from the 1820s onwards, engravers used the method to reproduce freehand line drawings. This was, in many ways an unnatural application, since engravers had to cut away almost all the surface of the block to produce the printable lines of the artist's drawing. Nonetheless, it became the most common use of wood engraving.

Examples include the cartoons of Punch magazine, the pictures in the Illustrated London News and Sir John Tenniel's illustrations to Lewis Carroll's works, the latter engraved by the firm of Dalziel Brothers. In the United States, wood-engraved publications also began to take hold, such as Harper's Weekly.

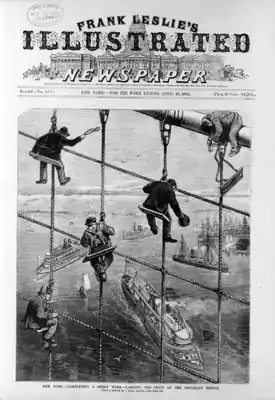

Frank Leslie, a British-born engraver who had headed the engraving department of the Illustrated London News, immigrated to the United States in 1848, where he developed a means to divide the labor for making wood engravings. A single design was divided into a grid, and each engraver worked on a square. The blocks were then assembled into a single image. This process formed the basis for his Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, which competed with Harper's in illustrating scenes from the American Civil War.

New techniques and technologies

By the mid-19th century, electrotyping was developed, which could reproduce a wood engraving on metal.[5] By this method, a single wood-engraving could be mass-produced for sale to printshops, and the original retained without wear.

Until 1860, artists working for engraving had to paint or draw directly on the surface of the woodblock and the original artwork was actually destroyed by the engraver. In 1860, however, the engraver Thomas Bolton invented a process for transferring a photograph onto the block.

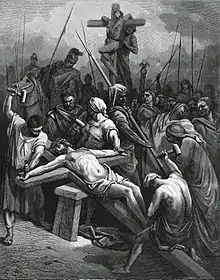

At about the same time, French engravers developed a modified technique (partly a return to that of Bewick) in which cross-hatching (one set of parallel lines crossing another at an angle) was almost entirely eliminated. Instead, all tonal gradations were rendered by white lines of varying thickness and closeness, sometimes broken into dots for the darkest areas. This technique appears in wood-engravings after Gustave Doré.

Towards the end of the 19th century, a combination of Bolton's 'photo on wood' process and the increased technical virtuosity initiated by the French school gave wood engraving a new application as a means of reproducing drawings in water-colour wash (as opposed to line drawings) and actual photographs. This is exemplified in illustrations in The Strand Magazine during the 1890s. With the new century, improvements in the half-tone process rendered this kind of reproductive engraving obsolete. In a less sophisticated form, it survived in advertisements and trade catalogues until about 1930. With this change, wood engraving was left free to develop as a creative form in its own right, a movement prefigured in the late 1800s by such artists as Joseph Crawhall II and the Beggarstaff Brothers.

Timothy Cole was a traditional wood engraver, executing copies from museum paintings on commission from magazines such as The Century Magazine.

Technique

Wood engraving blocks are typically made of boxwood or other hardwoods such as lemonwood or cherry. They are expensive to purchase because end-grain wood must be a section through the trunk or large bough of a tree. Some modern wood engravers use substitutes made of PVC or resin, mounted on MDF, which produce similarly detailed results of a slightly different character.

The block is manipulated on a "sandbag" (a sand-filled circular leather cushion). This helps the engraver produce curved or undulating lines with minimal manipulation of the cutting tool.

Wood engravers use a range of specialized tools. The lozenge graver is similar to the burin used by copper engravers of Bewick's day, and comes in different sizes. Various sizes of V-shaped graver are used for hatching. Other, more flexible, tools include the spitsticker, for fine undulating lines; the round scorper for curved textures; and the flat scorper for clearing larger areas.

Wood engraving is generally a black-and-white technique. However, a handful of wood engravers also work in colour, using three or four blocks of primary colours—in a way parallel to the four-colour process in modern printing. To do this, the printmaker must register the blocks (make sure they print in exactly the same place on the page). Recently, engravers have begun to use lasers to engrave wood.

Notable wood engravers

- Joseph Alexander Adams

- Leonard Baskin

- Thomas Bewick

- Torsten Billman

- Edward Calvert

- Vija Celmins

- Timothy Cole

- Arthur Comfort

- Rosemary Feit Covey

- Honoré Daumier

- John DePol

- Gustave Doré

- Nicolas Eekman

- Fritz Eichenberg

- Andy English

- M. C. Escher

- William Biscombe Gardner

- Tirzah Garwood

- Eric Gill

- Barbara Greg

- Gertrude Hermes

- Greta Hopkinson

- Barbara Howard

- Blair Hughes-Stanton

- Eduard Magnus Jakobson

- David Jones (poet)

- Rockwell Kent

- Paul Landacre

- Clare Leighton

- Frank Leslie

- William James Linton

- Iain Macnab

- Barry Moser

- Zdeněk Mézl

- John Nash

- Paul Nash

- Thomas Nast

- Agnes Miller Parker

- Garrick Palmer

- H.W. Peckwell

- Monica Poole

- Howard Pyle

- Eric Ravilious

- Gwen Raverat

- Don Rico

- Gaylord Schanilec

- Reynolds Stone

- John Thompson

- Leon Underwood

- Nora S. Unwin

- Félix Vallotton

- Manuel Vermeire

- Lynd Ward

- Richard Wagener

- Alexander Weygers

- John Buckland Wright

See also

- Flammarion engraving, a celebrated wood engraving.

References

- "Thomas Bewick 1753 - 1828". Tate Online. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- Richter, Emil Heinrich (1914). Prints : a brief review of their technique and history. Boston: Houghton. pp. 114–115, 118–119.

- Thomas Balston, English Wood-Engraving, 1900-1950 (London: Art & Technics, 1951), p. 4.

- Fuller, Sarah E. (1867). A Manual of Instruction in the Art of Wood Engraving. Boston: J. Watson. pp. 6–9.

- Emerson, William Andrew (1876). Practical Instruction in the Art of Wood Engraving. East Douglass, Mass.: C.J. Batcheller. pp. 51–52.

Bibliography

- Brett, Simon. An engravers globe( ) ISBN 1-901648-12-5

- Brett, Simon. Wood Engraving: How to do it (3rd ed. 2011 ) ISBN 1-901648-23-0; 1-901648-24-9 (hbk.)

- Simon Brett, Engravers: A Handbook for the Nineties (1987. Silent Books)

- Carrington, James B.. 'American Illustration and the Reproductive Arts', in Scribner's Magazine; ( July 1992), pp. 123–128.

- Garrett, Albert. British Wood Engraving of the 20th Century: A Personal View (1980)

- Garrett, Albert. A History of British Wood Engraving (1978)

- Taylor, Welford Dunaway "The Woodcut Art of J.J.Lankes" David R. Godine, Publisher. Boston pp. 112 ISBN 1-56792-049-7

- O'Donnell, Kevin E. "Book and Periodical Illustration [in America, 1820-1870]." American History through Literature, 1820–1870. Ed. Janet Gabler-Hover and Robert Sattelmeyer. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons (2006), 144-48.

- Pery, Jenny. A Being more Intense: the art of six wood engravers (2009. Oblong Creative, Wetherby, UK)

- Uglow, Jenny (2006). Nature's Engraver: A Life of Thomas Bewick. Faber and Faber.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wood engraving. |

- Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on wood engraving

- Wood Engravers Network

- Society of Wood Engravers

Hamerton, Philip; Spielmann, Marion (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 798–801.