Yenisei Kyrgyz

The Yenisei Kyrgyz (Old Turkic: 𐰶𐰃𐰺𐰴𐰕:𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣 Qïrqïz bodun), were an ancient Turkic people who dwelled along the upper Yenisei River in the southern portion of the Minusinsk Depression from the 3rd century BCE to the 13th century CE. The heart of their homeland was the forested Tannu-Ola mountain range (known in ancient times as the Lao or Kogmen mountains), in modern-day Tuva, just north of Mongolia. The Sayan mountains were also included in their territory at different times. The Kyrgyz Khaganate existed from 550 to 1219 CE; in 840, it took over the leadership of the Turkic Khaganate from the Uyghurs, expanding the state from the Yenisei territories into the Central Asia and the Tarim Basin. The Yenisei Kyrgyz mass migration to the Jeti-su resulted in the formation of the modern Kyrgyz Republic, land of the modern-day Kyrgyz.

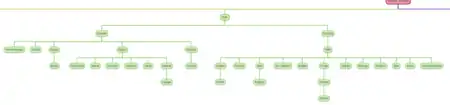

Yenisei Kyrgyz | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 539 CE–1219 CE | |||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Yenisei Kirghiz | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 539 CE | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1219 CE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Kyrgyzstan |

|

History

According to recent historical findings, Kyrgyz history dates back to 201 BC. The Yenisei Kyrgyz correlated with Čaatas culture and may perhaps be correlated to the Tashtyk culture.[1][2][3] Their endonym was variously transcribed in Chinese historical texts as Jiegu (結骨), Hegu (紇骨), Hegusi (紇扢斯), Hejiasi (紇戛斯), Hugu (護骨), Qigu (契骨), Juwu (居勿), and Xiajiasi (黠戛斯),[4] but first appeared as Gekun (or Ko-kun; Chinese: 鬲昆) or Jiankun (or Chien-kun; Chinese: 堅昆) in Han period records.[5] Peter Golden reconstructs underlying *Qïrğïz < *Qïrqïz< *Qïrqïŕ and suggests a derivation from Old Turkic qïr 'gray' (horse color) plus suffix -q(X)ŕ/ğ(X)ŕ ~ k(X)z/g(X)z.[6][7]

Duan Chengshi wrote in Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang that the mythological ancestors of Kyrgyz tribe (Jiānkūn bù 堅昆部) were "a god and a cow" (神與牸牛), (unlike Göktürks, whose mythological ancestress was a she-wolf; or Gaoche, whose mythological ancestors were a he-wolf and a daughter of a Xiongnu chanyu), and that Kyrgyzes' point of origin was a cave north of the Quman mountains (曲漫山),[8][9][10] which was identified with either the Sayan or the Tannu-Ola; additionally, Xin Tangshu mentioned that Kyrgyz army was stationed next to Qīngshān 青山 "Blue Mountains", calqued from Turkic Kögmän (> Ch. Quman) and the river Kem (> 劍 Jiàn).[11] By the time the Gokturk Empire fell in the eighth century CE, the Yenisei Kirghiz had established their own thriving state based on the Gokturk model. They had adopted the Orkhon script of the Göktürks and established trading ties with China and the Abbasid Caliphate in Central Asia and the Middle East.

The Kyrgyz Khagans of the Yenisei Kyrgyz Khaganate claimed descent from the Chinese general Li Ling, grandson of the famous Han Dynasty general Li Guang. Li Ling was captured by the Xiongnu and defected in the first century BCE and since the Tang royal Li family also claimed descent from Li Guang, the Kirghiz Khagan was therefore recognized as a member of the Tang Imperial family.[12][13]:394–395 Emperor Zhongzong of Tang had said to them that "Your nation and Ours are of the same ancestral clan (Zong). You are not like other foreigners."[14]:126

In 758, the Uyghurs killed the Kirghiz Khan and the Kirghiz came under the rule of the Uyghur Khaganate. However, the Yenisei Kyrghyz spent much of their time in a state of rebellion. In 840 they succeeded in sacking the Uyghur capital, Ordu-Baliq in Mongolia's Orkhon Valley and driving the Uyghurs out of Mongolia entirely.[15][16] On February 13 843 at "Kill the Foreigners" Mountain, the Tang Chinese inflicted a devastating defeat on the Uyghur Qaghan's forces.[14]:114– But rather than replace the Uyghurs as the lords of Mongolia, the Yenisei Kirghiz continued to live in their traditional homeland and exist as they had for centuries. The defeat and collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate triggered a massive migration of Uyghurs from Mongolia into Turfan, Kumul and Gansu, where they founded the Kingdom of Qocho and Gansu Uyghur Kingdom.

When Genghis Khan came to power in the early 13th century, the Yenisei Kirghiz submitted peacefully to him and were absorbed into his Mongol Empire, putting an end to their independent state. During the time of the Mongol Empire, the territory of the Yenisei Kirghiz in Northern Mongolia was turned into an agricultural colony called Kem-Kemchik. Kublai Khan, who founded the Yuan dynasty, also sent Mongolian and Chinese officials (along with colonists) to serve as judges in the Kyrgyz and Tuva regions.

Some of the Yenisei Kirghiz were relocated into the Dzungar Khanate by the Dzungars. In 1761, after the Dzungars were defeated by the Qing, some Öelet, a tribe of Oirat-speaking Dzungars, were deported to the Nonni basin in northeastern China (Manchuria) and a group of Yenisei Kirghiz were also deported along with the Öelet.[17][18] The Kirghiz moved to northeastern China became known as the Fuyu Kyrgyz, but they have now mostly merged with the Mongol and Chinese population.[19][20][21]

The descendants of the Yenisei Kirghiz today are the Kyrgyz, Khakas and Altai peoples.

Ethnicity and language

Culturally and linguistically, the Yenisei Kirghiz were Turkic. According to the Tang Huiyao (961 CE), which very likely comes from the Xu Huiyao that Yang Shaofu and others completed in 852, citing Protector General of Anxi Ge Jiayun, the Kirghiz were described as having primarily Caucasian features, with some having East Asian features.[22]

During the reign period of Kaiyuan of [emperor] Xuanzong, Ge Jiayun, composed A Record of the Western Regions, in which he said "the people of the Jiankun state all have red hair and green eyes. The ones with dark eyes were descendants of [the Chinese general] Li Ling [who was captured by the Xiongnu]... of Tiele tribe and called themselves Hegu. The change to Xiajiasi is probably because barbarian sounds are sometimes quick and sometimes slow so that the transcriptions of the words are not the same. When it is sometimes pronounced Xiajiasi, it is just that the word is quick. when I enquired from the translation clerk, he said that Xiajiasi had the meaning of 'yellow head and red face' and that this was what the Uighurs called them. Now the envoys say that they themselves have this name. I don't know which is right.

— Tang Huiyao, Chapter 100:1785; translated by Pulleyblank

From Xiajiasi 黠戛斯, Soviet scientists reconstructed the ethnonym Khakass.[23] Edwin G. Pulleyblank surmises that "red face and yellow head" meaning was possibly a folk etymology provided by an interpreter who explained the ethnonym based on Turkic qïzïl ~ qizqil, meaning 'red'.[24] The description of the Kirghiz as tall, blue-eyed blonds excited the early interest of scholars, who assumed that Kyrgyz might not have originally been Turkic in language. Golden considered Kyrghyzes to be Palaeo-Siberians Turkicized under Turkic leadership.[25] Ligeti cited the opinions of various scholars who had proposed to see them as Germanic, Slav, or Ket, while he himself, following Castrén and Schott, favoured a Samoyed origin on the basis of an etymology for a supposed Kirghiz word qaša or qaš for "iron". However Pulleyblank argued:[26]

As far as I can see the only basis for the assumption that the Kirghiz were not originally Turkic in language is the fact that they are described as blonds, hardly an acceptable argument in the light of present day ideas about the independence of language and race. As Ligeti himself admitted, other evidence about the Kirghiz language in Tang sources shows clearly that at that time they were Turkic speaking and there is no earlier evidence at all about their language. Even the word qaša or qaš may, I think, be Turkic. The Tongdian says: "Whenever the sky rains iron, they gather it and use it. They call it jiasha (LMC kiaa-şaa). They make knives and swords with it that are very sharp." The Tang Huiyao is the same except that it leaves out the foreign word jiasha. "Raining iron" must surely refer to meteorites. The editor who copied the passage into the Xin Tangshu unfortunately misunderstood it and changed it to, "Whenever it rains, their custom is always to get iron," which is rather nonsensical. Ligeti unfortunately used only the Xin Tangshu passage without referring to the Tongdian. His restoration of qaša or qaš seems quite acceptable but I doubt that word simply meant "iron". It seems rather to refer specifically to "meteorite" or "meteoric iron".

American Turkologist Michael Drompp adheres to the same opinion:[27]

A number of researchers have been tempted to see the early Kyrgyz as a non-Turkic people or, at the very least, an ethnically mixed people with a large non-Turkic component. Many scholars have supported this idea after identifying what they believe to be examples of non-Turkic (particularly Samoyed) words among the Kyrgyz words preserved in Chinese sources. It should be noted, however, that the connection between language and "race" is highly inconclusive. The physical appearance of the Kyrgyz can no more be considered as indicating that they were not a Turkic people than can the lexical appearance of a few possibly non-Turkic words, whose presence in the Kyrgyz language can be explained through the common practice of linguistic borrowing. The Kyrgyz inscriptions of the Yenisei (eighth century CE and later) are in fact written in a completely Turkic language, and T'ang Chinese sources state clearly that the Kyrgyz written and spoken language at that time was identical to that of the Turkic Uygurs (Chinese Hui-ho, Hui-hu). Most of the Kyrgyz words preserved in Chinese sources are, in fact, Turkic. There is no reason to assume a non-Turkic origin for the Kyrgyz, although that possibility cannot be discounted.

Lifestyle

The Yenisei Kirghiz had a mixed economy based on traditional nomadic animal breeding (mostly horses and cattle) and agriculture. According to Chinese records, they grew Himalayan rye, barley, millet, and wheat.[13]:400–401 They were also skilled iron workers, jewelry makers, potters, and weavers. Their homes were traditional nomadic tents and, in the agricultural areas, wood and bark huts. Their farming settlements were protected by log palisades. The resources of their forested homeland (mainly fur) allowed the Yenisei Kirghiz to become prosperous merchants as well. They maintained trading ties with China, Tibet, the Abbasid Caliphate of the Middle east, and many local tribes.[13]:402 Kirghiz horses were also renowned for their large size and speed. The tenth-century Persian text Hudud al-'alam described the Kirgiz as people who "venerate the Fire and burn the dead", and that they were nomads who hunted.[28]

Etymology and names

The trisyllabic forms with Chinese -sz for Turkic final -z appear only from the end of 8th century onward. Before that time we have a series of Chinese transcriptions referring to the same people and stretching back to the 2nd century BCE, which end either in -n or -t:

- Gekun (EMC kέrjk kwən), 2nd century BCE. Shiji 110, Hanshu 94a.

- Jiankun (EMC khέn kwən), 1st century BCE onward. Hanshu 70.

- Qigu (EMC kέt kwət), 6th century. Zhoushu 50.

- Hegu (EMC γət kwət), 6th century. Suishu 84.

- Jiegu (EMC kέt kwət), 6th–8th century. Tongdian 200, Old Book of Tang 194b, and Tang Huiyao 100.

Neither -n nor -t provides a good equivalent for -z. The most serious attempt to explain these forms seems still to be that of Paul Pelliot in 1920. Pelliot suggested that Middle Chinese -t stands for Turkic -z, which would be quite unusual and would need supporting evidence, but then his references to Mongol plurals in -t suggest that he thinks that the name of the Kirghiz, like that of the Turks, first became known to the Chinese through Mongol speaking intermediaries. There is still less plausibility in the suggestion that the Kirghiz, who first became known as a people conquered by that Xiongnu and then re-emerged associated with other Turkic peoples in the 6th century, should have had Mongol style suffixes attached to all the various forms of their name that were transcribed into Chinese up to the 9th century.

The change of r to z in Turkic which is implied by the Chinese forms of the name Kirghiz should not give any comfort to those who want to explain Mongolian and Tungusic cognates with r as Turkic loanwords. The peoples mentioned in sources of the Han period that can be identified as Turkic were the Dingling (later Tiele, from whom the Uyghurs emerged), the Jiankun (later Kirghiz), the Xinli (later Sir/Xue), and possibly also the Hujie or Wujie, were all, at that period, north and west of the Xiongnu in general area where we find the Kirghiz at the beginning of Tang.

Further reading

- Chavannes, Edouard. "Documents sur les Tou-kiue (Turcs) occidentaux" ("Documents on the Western Tujue") (1904)

- Mambetaliev Askar. "Nestorianism among ancient Kirghiz tribes"

References

- "Xipoliya Yanke Suo Jian Xiajiesi Monijiao" ("Siberian Rock Arts and Xiajiesi's Manicheism") 1998 Gansu Mingzu Yanjiu

- A. J. Haywood, Siberia: A Cultural History, Oxford University Press, 2010, p.203

- Christoph Baumer, The History of Central Asia: The Age of the Steppe Warriors, I.B.Tauris, 2012, p.171

- Theobald, Ulrich (2012). "Xiajiasi 黠戛斯, Qirqiz" for ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. "The Name of the Kirghiz" in Central Asiatic Journal, Vol. 34, No. 1/2 (1990). Harrassowitz Verlag. page 98-99 of 98-108

- Golden, Peter B. (2017). "The Turkic World in Mahmûd al-Kâshgarî" (PDF). Türkologiya 4: 16.

- Golden, Peter B. (August 2018). "The Ethnogonic Tales of the Türks". The Medieval History Journal, 21(2): 302.

- Youzang Zazu vol. 4

- Lee & Kuang (2017) "A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and Y-DNA Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples", Inner Asia 19. p. 204-205 of 197-239

- Golden, Peter B. (August 2018). "The Ethnogonic Tales of the Türks". The Medieval History Journal, 21(2): 297-304

- Kenzheakhmet, Nurlan (2014). "Ethnonyms and Toponyms" of the Old Turkic Inscriptions in Chinese sources". Studia et Documenta Turcologica. II. p. 299 of 287–316.

- Veronika Veit, ed. (2007). The role of women in the Altaic world: Permanent International Altaistic Conference, 44th meeting, Walberberg, 26-31 August 2001. Volume 152 of Asiatische Forschungen (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 61. ISBN 978-3447055376. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- Michael R. Drompp (1999). "Breaking the Orkhon tradition: Kirghiz adherence to the Yenisei region after A. D. 840". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 119 (3): 390–403. doi:10.2307/605932. JSTOR 605932.

- Michael Robert Drompp (2005). Tang China and the collapse of the Uighur Empire: a documentary history. Brill's Inner Asian library. 13. Brill. ISBN 9004141294.

- Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. April 6, 2010. pp. 610–. ISBN 978-0-08-087775-4.

- Pál Nyíri; Joana Breidenbach (2005). China Inside Out: Contemporary Chinese Nationalism and Transnationalism. Central European University Press. pp. 275–. ISBN 978-963-7326-14-1.

- Juha Janhunen (1996). Manchuria: An Ethnic History. Finno-Ugrian Society. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-951-9403-84-7.

- Stephen A. Wurm; Peter Mühlhäusler; Darrell T. Tryon, eds. (February 11, 2011). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas. de Gruyter. p. 831. ISBN 9783110819724.

- Tchoroev (Chorotegin) 2003, p. 110.

- Pozzi & Janhunen & Weiers 2006, p. 113.

- Giovanni Stary; Alessandra Pozzi; Juha Antero Janhunen; Michael Weiers (2006). Tumen Jalafun Jecen Aku: Manchu Studies in Honour of Giovanni Stary. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 112–. ISBN 978-3-447-05378-5.

- Lung, Rachel (2011). Interpreters in Early Imperial China. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 108. ISBN 978-9027224446. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- Lee & Kuang (2017) "A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and Y-DNA Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples", Inner Asia 19. p. 216 of 197-239

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. "The Name of the Kirghiz" in Central Asiatic Journal, Vol. 34, No. 1/2 (1990). Harrassowitz Verlag. page 105 of 98-108

- Golden, Peter B. “The Stateless Nomads of Central Eurasia”, in Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity Edited by DiCosmo, Maas. p. 347-348. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316146040.024

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G (2002). Central Asia and Non-Chinese Peoples of Ancient China. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-86078-859-8.

- Drompp, Michael (2002). "THE YENISEI KYRGYZ FROM EARLY TIMES TO THE MONGOL CONQUEST". Academia. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- Scott Cameron Levi, Ron Sela (2010). "Chapter 4, Discourse on the Qïrghïz Country". Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.