Tarim Basin

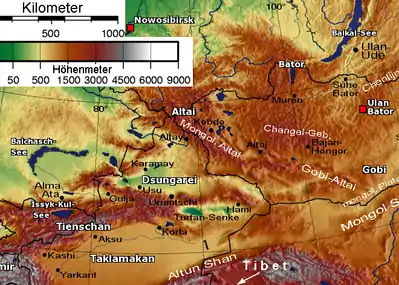

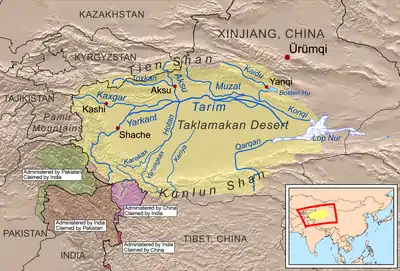

The Tarim Basin is an endorheic basin in Northwest China occupying an area of about 1,020,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi).[1][2] Located in China's Xinjiang region, it is sometimes used synonymously to refer to the southern half of the province, or Nanjiang (Chinese: 南疆; pinyin: Nánjiāng; lit. 'Southern Xinjiang'), as opposed to the northern half of the province known as Dzungaria or Beijiang. Its northern boundary is the Tian Shan mountain range and its southern boundary is the Kunlun Mountains on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. The Taklamakan Desert dominates much of the basin. The historical Uyghur name for the Tarim Basin is Altishahr (Traditional spelling: آلتی شهر), which means 'six cities' in Uyghur.

| Tarim Basin | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 塔里木盆地 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Nanjiang | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 南疆 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Southern Xinjiang | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||

| Uyghur | تارىم ئويمانلىقى | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Geography and relation to Xinjiang

Xinjiang consists of two main geographically, historically, and ethnically distinct regions with different historical names, Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin (Altishahr), before Qing China unified them into one political entity called Xinjiang province in 1884.[3] At the time of the Qing conquest in 1759, Dzungaria was inhabited by steppe dwelling, nomadic Tibetan Buddhist Dzungar people, while the Tarim Basin (Altishahr) was inhabited by sedentary, oasis dwelling, Turkic speaking Muslim farmers, now known as the Uyghur people. They were governed separately until 1884.

Tarim Basin locations

- North side

The Chinese called this the Tien Shan Nan Lu or Tien Shan South Road, as opposed to the Bei Lu north of the mountains. Along it runs the modern highway and railroad while the middle Tarim River is about 100 km south. Kashgar was where the caravans met before crossing the mountains. Bachu or Miralbachi; Uchturpan north of the main road; Aksu on the large Aksu River; Kucha was once an important kingdom; Luntai; Korla, now a large town; Karashar near Bosten Lake; Turpan north of the Turpan Depression and south of the Bogda Shan; Hami; then southeast to Anxi and the Gansu Corridor.

- Center

Most of the basin is occupied by the Taklamakan Desert which is too dry for permanent habitation. The Yarkand, Kashgar and Aksu Rivers join to form the Tarim River which runs along the north side of the basin. Formerly it continued to Loulan, but some time after 330AD it turned southeast near Korla toward Charkilik and Loulan was abandoned. The Tarim ended at the now-dry Lop Nur which occupied a changing position east of Loulan. Eastward is the fabled Jade Gate which the Chinese considered the gateway to the Western Regions. Beyond that is Dunhuang with its ancient manuscripts and then Anxi at the west end of the Gansu Corridor.

- South side

Kashgar; Yangi Hissar, famous for its knives; Yarkand, once larger than Kashgar; Karghalik (Yecheng), with a route to India; Karakash; Khotan, the main source of Chinese jade; eastward the land becomes more desolate; Keriya (Yutian); Niya (Minfeng); Qiemo (Cherchen); Charkilik (Ruoqiang). The modern road continues east to Tibet. There is no current road east across the Kumtag Desert to Dunhuang, but caravans somehow made the crossing through the Yangguan pass south of the Jade Gate.

Roads and passes, rivers and caravan routes

_2.jpg.webp)

The Southern Xinjiang Railway branches from the Lanxin Railway near Turpan, follows the north side of the basin to Kashgar and curves southeast to Khotan.

- Roads

The main road from eastern China reaches Urumchi and continues as highway 314 along the north side to Kashgar. Highway 315 follows the south side from Kashgar to Charkilik and continues east to Tibet. There are currently four north-south roads across the desert. 218 runs from Charkilik to Korla along the former course of the Tarim forming an oval whose other end is Kashgar. The Tarim Desert Highway, a major engineering achievement, crosses the center from Niya to Luntai. The new Highway 217 follows the Khotan River from Khotan to near Aksu. A road follows the Yarkand River from Yarkand to Baqu. East of the Korla-Charkilik road travel continues to be very difficult.

- Rivers

Rivers coming south from the Tien Shan join the Tarim, the largest being the Aksu. Rivers flowing north from the Kunlun are usually named for the town or oasis they pass through. Most dry up in the desert, only the Hotan River reaching the Tarim in good years. An exception is the Qiemo River which flowed northeast into Lop Nor. Ruins in the desert imply that these rivers were once larger.

- Caravans and passes

The original caravan route seems to have followed the south side. At the time of the Han Dynasty conquest it shifted to the center (Jade Gate-Loulan-Korla). When the Tarim changed course about 330AD it shifted north to Hami. A minor route went north of the Tian Shan. When there was war on the Gansu Corridor trade entered the basin near Charkilik from the Qaidam Basin. The original route to India seems to have started near Yarkand and Kargilik, but it is now replaced by the Karakoram Highway south from Kashgar. To the west of Kashgar via the Irkeshtam border crossing is the Alay Valley which was once the route to Persia. Northeast of Kashgar the Torugart pass leads to the Ferghana Valley. Near Uchturpan the Bedel Pass leads to Lake Issyk-Kul and the steppes. Somewhere near Aksu the difficult Muzart Pass led north to the Ili River basin (Kulja). Near Korla was the Iron Gate Pass and now the highway and railway north to Urumchi. From Turfan the easy Dabancheng pass leads to Urumchi. The route from Charkilik to the Qaidam Plateau was of some importance when Tibet was an empire.

North of the Mountains is Dzungaria with its central Gurbantünggüt Desert, Urumchi the capital and the Karamay oil fields. The Kulja territory is the upper basin of the Ili River and opens out onto the Kazakh steppe with several roads eastward. The Dzungarian Gate was once a migration route and is now a road and rail crossing. Tacheng or Tarbaghatay is a road crossing and former trading post.

Geology

The Tarim Basin is the result of an amalgamation between an ancient microcontinent and the growing Eurasian continent during the Carboniferous to Permian periods. At present, deformation around the margins of the basin is resulting in the microcontinental crust being pushed under Tian Shan to the north, and Kunlun Shan to the south.

A thick succession of Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary rocks occupy the central parts of the basin, locally exceeding thicknesses of 15 km (9 mi). The source rocks of oil and gas tend to be mostly Permian mudstones and, less often, Ordovician strata which experienced an intense and widespread early Hercynian karstification. The effect of this event are e.g. paleokarst reservoirs in the Tahe oil field.[4] Below the level enriched with gas and oil is a complex Precambrian basement believed to be made up of the remnants of the original Tarim microplate, which accrued to the growing Eurasian continent in Carboniferous time. The snow on K2, the second highest mountain in the world, flows into glaciers which move down the valleys to melt. The melted water forms rivers which flow down the mountains and into the Tarim Basin, never reaching the sea. Surrounded by desert, some rivers feed the oases where the water is used for irrigation while others flow to salt lakes and marshes.

Lop Nur is a marshy, saline depression at the east end of the Tarim Basin. The Tarim River ends in Lop Nur.

The Tarim Basin is believed to contain large potential reserves of petroleum and natural gas.[5]:493 Methane comprises over 70 percent of the natural gas reserve, with variable contents of ethane (<1% ~18%) and propane (<0.5% ~9%).[6] China National Petroleum Corporation's comprehensive exploration of the Tarim basin between 1989 and 1995 led to the identification of 26 oil- and gas-bearing structures. These occur at deeper depths and in scattered deposits. Beijing aims to develop Xinjiang into China's new energy base for the long run, supplying one-fifth of the country's total oil supply by 2010, with an annual output of 35 million tonnes.[7] On June 10, 2010 Baker Hughes announced an agreement to work with PetroChina Tarim Oilfield Co. to supply oilfield services, including both directional and vertical drilling systems, formation evaluation services, completion systems and artificial lift technology for wells drilled into foothills formations greater than 7,500 meters (24,600 feet) deep with pressures greater than 20,000 psi (1379 bar) and bottomhole temperatures of approximately 160 °C (320 °F). Electrical submersible pumping (ESP) systems will be employed to dewater gas and condensate wells. PetroChina will fund any joint development.[8]

In 2015, Chinese researchers published the finding of a vast, carbon-rich underground sea beneath the basin.[9]

History

It is speculated that the Tarim Basin may be one of the last places in Asia to have become inhabited: It is surrounded by mountains and irrigation technologies might have been necessary.[10]

The Northern Silk Road on one route bypassed the Tarim Basin north of the Tian Shan mountains and traversed it on three oases-dependent routes: one north of the Taklamakan Desert, one south, and a middle one connecting both through the Lop Nor region.

- The northern Tarim route ran from Kashgar over Aksu, Kucha, Korla, through the Iron Gate Pass, over Karasahr, Jiaohe, Turpan, Gaochang and Kumul to Anxi.

- The southern Tarim route ran from Kashgar over Yarkant, Karghalik, Pishan, Khotan, Keriya, Niya, Qarqan, Qarkilik, Miran and Dunhuang to Anxi.

- The middle Tarim route, allowing the shortest possible itinerary of all four routes, connected Korla on the northern Tarim route over Loulan across the Lop Nor region with Dunhuang on the southern Tarim route. The Lop Nor region became uninhabitable in the 4th century and the middle route has been deserted since the 6th century.

Early periods

The earliest inhabitants of the Tarim Basin may be the Tocharians whose languages are the easternmost group of Indo-European languages. Caucasoid mummies have been found in various locations in the Tarim Basin such as Loulan, the Xiaohe Tomb complex, and Qäwrighul. These mummies have been suggested to be of Tocharian origin, and these people may have inhabited the region since at least 1800 BCE. They may be related to the "Yuezhi" (Chinese 月氏; Wade–Giles: Yüeh-Chih) mentioned in Chinese texts. Protected by the Taklamakan Desert from steppe nomads, elements of Tocharian culture survived until the 7th century, at the dawning of the 800s with the arriving Turkic immigrants from the collapsing Uyghur Khaganate of modern-day Mongolia began to absorb the Tocharians to form the modern-day Uyghur ethnic group.[11]

Righthand image: Two Buddhist monks on a mural of the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves near Turpan, Xinjiang, China, 9th century AD; although Albert von Le Coq (1913) assumed the blue-eyed, red-haired monk was a Tocharian,[12] modern scholarship has identified similar Caucasian figures of the same cave temple (No. 9) as ethnic Sogdians,[13] an Eastern Iranian people who inhabited Turfan as an ethnic minority community during the phases of Tang Chinese (7th-8th century) and Uyghur rule (9th-13th century).[14]

Another people in the region besides Tocharian are the Indo-Iranian Saka people who spoke various Eastern Iranian Khotanese Scythian or Saka dialects. In the Achaemenid-era Old Persian inscriptions found at Persepolis, dated to the reign of Darius I (r. 522-486 BC), the Saka are said to have lived just beyond the borders of Sogdiana.[15] Likewise an inscription dated to the reign of Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BC) has them coupled with the Dahae people of Central Asia.[15] The contemporary Greek historian Herodotus noted that the Achaemenid Persians called all of the Indo-Iranian Scythian peoples as the Saka.[15] They were known as the Sai (塞, sāi, sək in archaic Chinese) in ancient Chinese records.[16] These records indicate that they originally inhabited Ili and Chu River valleys of modern Kazakhstan. In the Chinese Book of Han, the area was called the "land of the Sai", i.e. the Saka.[17] Presence of a people believed to be Saka has also been found in various location in the Tarim Basin, for example in the Keriya region at Yumulak Kum (Djoumboulak Koum, Yuansha) around 200 km east of Khotan, with a tomb dated to as early as the 7th century BC.[18][19]

According to the Sima Qian's Shiji, the nomadic Indo-European Yuezhi originally lived between Tengri Tagh (Tian Shan) and Dunhuang of Gansu, China.[20] However, the Yuezhi were assaulted and forced to flee from the Hexi Corridor of Gansu by the forces of the Xiongnu ruler Modu Chanyu, who conquered the area in 177-176 BC (decades before the Han Chinese conquest and colonization of Gansu or the establishment of the Protectorate of the Western Regions).[21][22][23][24] In turn the Yuezhi were responsible for attacking and pushing the Sai (i.e. Saka) west into Sogdiana, where in the mid 2nd century BC the latter crossed the Syr Darya into Bactria, but also into the Fergana Valley where they settled in Dayuan, southwards towards northern India, and eastward as well where they settled in some of the oasis city-states of the Tarim Basin.[25] Whereas the Yuezhi continued westward and conquered Daxia around 177-176 BC, the Sai (i.e. Saka), including some allied Tocharian peoples, fled south to the Pamirs before heading back east to settle in Tarim Basin sites like Yanqi (焉耆, Karasahr) and Qiuci (龜茲, Kucha).[26] The Saka are recorded as inhabiting Khotan by at least the 3rd century and also settled in nearby Shache (莎車), a town named after the Saka inhabitants (i.e. saγlâ).[27] Although the ancient Chinese had called Khotan Yutian (于闐), it's more native Iranian names during the Han period were Jusadanna (瞿薩旦那), derived from Indo-Iranian Gostan and Gostana, the names of the town and region around it, respectively.[28]

Han dynasty

Around 200 BCE, the Yuezhi were overrun by the Xiongnu. The Xiongnu tried to invade the western region of China, but ultimately failed and lost control of the region to the Chinese. The Han Chinese wrested control of the Tarim Basin from the Xiongnu at the end of the 1st century under the leadership of General Ban Chao (32–102 CE), during the Han-Xiongnu War.[29] The Chinese administered the Tarim Basin as the Protectorate of the Western Regions. The Tarim Basin was later under many foreign rulers, but ruled primary by Turkic, Han, Tibetan, and Mongolic peoples.

The powerful Kushans, who conquered the last vestiges of the Indo-Greek Kingdom, expanded back into the Tarim Basin in the 1st–2nd centuries CE, where they established a kingdom in Kashgar and competed for control of the area with nomads and Chinese forces. The Yuezhi or Rouzhi (Chinese: 月氏; pinyin: Yuèzhī; Wade–Giles: Yüeh4-chih1, [ɥê ʈʂɻ̩́]) were an ancient people first reported in Chinese histories as nomadic pastoralists living in an arid grassland area in the western part of the modern Chinese province of Gansu, during the 1st millennium BC. After a major defeat by the Xiongnu, during the 2nd century BC, the Yuezhi split into two groups: the Greater Yuezhi (Dà Yuèzhī 大月氏) and Lesser Yuezhi (Xiǎo Yuèzhī 小月氏). They introduced the Brahmi script, the Indian Prakrit language for administration, and Buddhism, playing a central role in the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism to Eastern Asia.

Three pre-Han texts mention peoples who appear to be the Yuezhi, albeit under slightly different names.[30]

- The philosophical tract Guanzi (73, 78, 80 and 81) mentions nomadic pastoralists known as the Yúzhī 禺氏 (Old Chinese: *ŋʷjo-kje) or Niúzhī 牛氏 (OC: *ŋʷjə-kje), who supplied jade to the Chinese.[31][30] (The Guanzi is now generally believed to have been compiled around 26 BC, based on older texts, including some from the Qi state era of the 11th to 3rd centuries BC. Most scholars no longer attribute its primary authorship to Guan Zhong, a Qi official in the 7th century BC.[32]) The export of jade from the Tarim Basin, since at least the late 2nd millennium BC, is well-documented archaeologically. For example, hundreds of jade pieces found in the Tomb of Fu Hao (c. 1200 BC) originated from the Khotan area, on the southern rim of the Tarim Basin.[33] According to the Guanzi, the Yúzhī/Niúzhī, unlike the neighbouring Xiongnu, did not engage in conflict with nearby Chinese states.

- The Tale of King Mu, Son of Heaven (early 4th century BC) also mentions the Yúzhī 禺知 (OC: *ŋʷjo-kje).[30]

- The Yi Zhou Shu (probably dating from the 4th to 1st century BC) makes separate references to the Yúzhī 禺氏 (OC: *ŋʷjo-kje) and Yuèdī 月氐 (OC: *ŋʷjat-tij). The latter may be a misspelling of the name Yuèzhī 月氏 (OC: *ŋʷjat-kje) found in later texts, composed of characters meaning "moon" and "clan" respectively.[30]

Sui–Tang dynasties

After the Han dynasty, the Kingdoms of the Tarim Basin began to have strong cultural influences on China as a conduit between the cultures of India and Central Asia to China. Indian Buddhists had previously travelled to China during the Han dynasty, but the Buddhist monk Kumārajīva from Kucha who visited China during the Six dynasties was particularly renowned. The music and dances from Kucha were also popular in the Sui and Tang periods.[34]

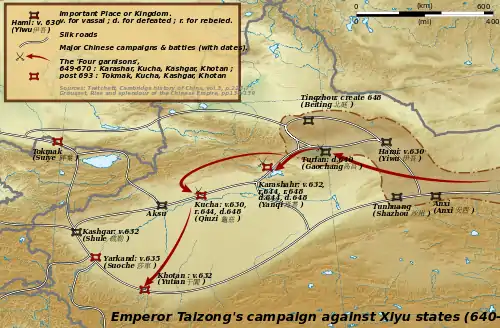

During the Tang Dynasty, a series of military expeditions were conducted against the oasis states of the Tarim Basin, then vassals of the Western Turkic Khaganate.[35] The campaigns against the oasis states began under Emperor Taizong with the annexation of Gaochang in 640.[36] The nearby kingdom of Karasahr was captured by the Tang in 644 and the kingdom of Kucha was conquered in 649.[37]

The expansion into Central Asia continued under Taizong's successor, Emperor Gaozong, who dispatched an army in 657 led by Su Dingfang against the Western Turk qaghan Ashina Helu.[37] Ashina was defeated and the khaganate was absorbed into the Tang empire.[38] The Tarim Basin was administered through the Anxi Protectorate and the Four Garrisons of Anxi. Tang hegemony beyond the Pamir Mountains in modern Tajikistan and Afghanistan ended with revolts by the Turks, but the Tang retained a military presence in Xinjiang. These holdings were later invaded by the Tibetan Empire to the south in 670. For the remainder of the Tang Dynasty, the Tarim Basin alternated between Tang and Tibetan rule as they competed for control of Central Asia.[39]

Kingdom of Khotan

As a consequence of the Han–Xiongnu War spanning from 133 BC to 89 AD, the Tarim Basin region of Xinjiang in Northwest China, including the Saka-founded oasis city-state of Khotan and Kashgar, fell under Han Chinese influence, beginning with the reign of Emperor Wu (r. 141-87 BC) of the Han Dynasty.[40][41] Much like the neighboring people of the Kingdom of Khotan, people of Kashgar, the capital of the Shule Kingdom, spoke Saka, one of the Eastern Iranian languages.[42] As noted by the Greek historian Herodotus, the contemporary Persians labelled all Scythians as the Saka.[15] Indeed, modern scholarly consensus is that the Saka language, ancestor to the Pamir languages in northern India and Khotanese in Xinjiang, China belongs to the Scythian languages.[43]

During China's Tang dynasty (618-907 AD), the region once again came under Chinese suzerainty with the campaigns of conquest by Emperor Taizong of Tang (r. 626-649).[44] From the late 8th to 9th centuries, the region changed hands between the Chinese Tang Empire and the rival Tibetan Empire.[45][46] By the early 11th century the region fell to the Muslim Turkic peoples of the Kara-Khanid Khanate, which led to both the Turkification of the region as well as its conversion from Buddhism to Islam.[47][48]

Suggestive evidence of Khotan's early link to India are minted coins from Khotan dated to the 3rd century bearing dual inscriptions in Chinese and Gandhari Prakrit in the Kharosthi script.[49] Although Prakrit was the administrative language of nearby Shanshan, 3rd-century documents from that kingdom record the title hinajha (i.e. "generalissimo") for the king of Khotan, Vij'ida-simha, a distinctively Iranian-based word equivalent to the Sanskrit title senapati, yet nearly identical to the Khotanese Saka hīnāysa attested in contemporary documents.[49] This along with the fact that the king's recorded regnal periods were given in Khotanese as kṣuṇa, "implies an established connection between the Iranian inhabitants and the royal power", according to the late Professor of Iranian Studies Ronald E. Emmerick (d. 2001).[49] He contended that Khotanese-Saka-language royal rescripts of Khotan dated to the 10th century "makes it likely that the ruler of Khotan was a speaker of Iranian."[49] Furthermore, he elaborated on the early name of Khotan:

The name of Khotan is attested in a number of spellings, of which the oldest form is hvatana, in texts of approximately the 7th to the 10th century AD written in an Iranian language itself called hvatana by the writers. The same name is attested also in two closely related Iranian dialects, Sogdian and Tumshuq...Attempts have accordingly been made to explain it as Iranian, and this is of some importance historically. My own preference is for an explanation connecting it semantically with the name Saka, for the Iranian inhabitants of Khotan...[50]

Obv: Kharosthi legend, "Of the great king of kings, king of Khotan, Gurgamoya.

Rev: Chinese legend: "Twenty-four grain copper coin". British Museum

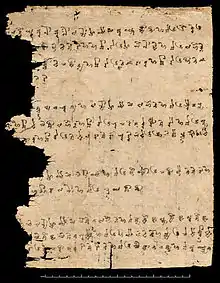

In Northwest China, Khotanese-Saka-language documents, ranging from medical texts to Buddhist literature, have been found primarily in Khotan and Tumshuq (northeast of Kashgar).[51] They largely predate the arrival of Islam to the region under the Turkic Kara-Khanids.[51] Similar documents in the Khotanese-Saka language were found in Dunhuang dating mostly to the 10th century.[52]

Turkic influx

The collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate in 840 AD led to the movement of the Uyghurs south to Turpan and Gansu, and some absorbed by the Karluks. Tocharian languages became extinct due to Uyghur migrations to these areas. The Uyghurs of Turfan (or Qocho) became Buddhists. In the tenth century, the Karluks, Yagmas, Chigils and other Turkic tribes founded the Kara-Khanid Khanate in Semirechye, Western Tian Shan, and Kashgaria.[53]

Islamisation of the Tarim Basin

The Karakhanids became the first Islamic Turkic dynasty in the tenth century when Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan converted to Islam in 966 and controlled Kashgar.[53] Satuq Bughra Khan and his son directed endeavors to preach Islam among the Turks and engage in conquests.[54] Satok Bughra Khan's nephew or grandson Ali Arslan was slain by the Buddhists during the war. Buddhism lost territory to the Turkic Karakhanid Satok Bughra Khan during the Karakhanid reign around the Kashgar area.[55] The Tarim Basin became Islamicized over the next few centuries.

Turkic-Islamic Kara-Khanid conquest of Iranic Saka Buddhist Khotan

In the tenth century, the Buddhist Iranic Saka Kingdom of Khotan was the only city-state that was not conquered yet by the Turkic Uyghur (Buddhist) and the Turkic Qarakhanid (Muslim) states. The Buddhist entitites of Dunhuang and Khotan had a tight-knit partnership, with intermarriage between Dunhuang and Khotan's rulers and Dunhuang's Mogao grottos and Buddhist temples being funded and sponsored by the Khotan royals, whose likenesses were drawn in the Mogao grottoes.[56] Halfway in the 10th century Khotan came under attack by the Qarakhanid ruler Musa, a long war ensued between the Turkic Karakhanid and Buddhist Khotan which eventually ended in the conquest of Khotan by Kashgar by the Karakhanid leader Yusuf Qadir Khan around 1006.[56][57]

Accounts of the Muslim Karakhanid war against the Khotanese Buddhists are given in Taẕkirah of the Four Sacrificed Imams written sometime in the period from 1700-1849 which told the story of four imams from Mada'in city (possibly in modern-day Iraq) who travelled to help the Islamic conquest of Khotan, Yarkand, and Kashgar by Yusuf Qadir Khan, the Qarakhanid leader.[58] The "infidels" were defeated and driven towards Khotan by Yusuf Qadir Khan and the four Imams, but the Imams were assassinated by the Buddhists prior to the last Muslim victory. After Yusuf Qadir Khan's conquest of new land in Altishahr towards the east, he adopted the title "King of the East and China".[58]

In 1006, the Muslim Kara-Khanid ruler Yusuf Kadir (Qadir) Khan of Kashgar conquered Khotan, ending Khotan's existence as an independent state. The Islamic conquest of Khotan led to alarm in the east and Dunhuang's Cave 17, which contained Khotanese literary works, was closed shut possibly after its caretakers heard that Khotan's Buddhist buildings were razed by the Muslims, the Buddhist religion had suddenly ceased to exist in Khotan.[54] The Karakhanid Turkic Muslim writer Mahmud al-Kashgari recorded a short Turkic language poem about the conquest:

Conversion of the Buddhist Uyghurs

The Buddhist Uyghurs of the Kingdom of Qocho and Turfan embraced Islam after conversion at the hands of the Muslim Chagatai Khizr Khwaja.[56]

Kara Del was a Mongolian ruled and Uighur populated Buddhist Kingdom. The Muslim Chagatai Khan Mansur invaded and used the sword to make the population convert to Islam.[63]

After being converted to Islam, the descendants of the previously Buddhist Uyghurs in Turfan believed that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungars) were the ones who built Buddhist monuments in their area, in opposition to the current academic theory that it was their own ancestral legacy.[64]

Before Qing conquest

Southern region of Tarim basin had influence by Naqshbandi Sufis in seventeenth century.[65]

Qing dynasty

Xinjiang did not exist as one unit until 1884 under Qing rule. It consisted of the two separate political entities of Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin (Eastern Turkestan).[66][67][68][69] Dzungharia or Ili was called Zhunbu 準部 (Dzungar region) Tianshan Beilu 天山北路 (Northern March), "Xinjiang" 新疆 (New Frontier),[70] or "Kalmykia" (La Kalmouquie in French).[71][72] It was formerly the area of the Dzungar (or Zunghar) Khanate 準噶爾汗國, the land of the Dzungar people. The Tarim Basin was known as "Tianshan Nanlu 天山南路 (southern March), Huibu 回部 (Muslim region), Huijiang 回疆 (Muslim frontier), Chinese Turkestan, Kashgaria, Little Bukharia, East Turkestan", and the traditional Uyghur name for it was Altishahr (Uighur: التى شهر, romanized: Altä-shähär, Алтә-шәһәр).[73] It was formerly the area of the Eastern Chagatai Khanate 東察合台汗國, land of the Uyghur people before being conquered by the Dzungars.

People of Tarim Basin

According to census figures, the Tarim Basin is dominated by the Uyghurs.[74] They form the majority population in cities such as Kashgar, Artush, and Hotan. There are however large pockets of Han Chinese in the region, such as Aksu and Korla. There are also smaller numbers of Hui and other ethnic groups, for example, the Tajiks who are concentrated at Tashkurgan in the Kashgar Prefecture, the Kyrgyz in Kizilsu, and the Mongols in Bayingolin.[75]

The discovery of the Tarim mummies showed that the early people of the Tarim Basin were Europoids.[76] According to Sinologist Victor H. Mair: "From around 1800BC, the earliest mummies in the Tarim Basin were exclusively Caucasoid, or Europoid." He also said that East Asian migrants arriving in the eastern portions of the Tarim Basin around 3,000 years ago, and the Uyghur peoples "arrived after the collapse of the Orkon Uighur Kingdom, based in modern-day Mongolia, around the year 842." He also noted that the people of Xinjiang are a mixture: "Modern DNA and ancient DNA show that Uighurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyzs, the peoples of central Asia are all mixed Caucasian and East Asian. The modern and ancient DNA tell the same story."[11] Professor James A. Millward described the original Uyghurs as physically Mongoloid, giving as an example the images in Bezeklik at Temple 9 of the Uyghur patrons, until they began to mix with the Tarim Basin's original Tocharian and eastern Iranian inhabitants.[77]

The modern Uyghurs are now a mixed hybrid of East Asians and Europoids.[78][79][80]

Archaeology

Although archaeological findings are of interest in the Tarim Basin, the prime impetus for exploration was petroleum and natural gas. Recent research with help of GIS database have provided a fine-grained analysis of the ancient oasis of Niya on the Silk Road. This research led to significant findings; remains of hamlets with wattle and daub structures as well as farm land, orchards, vineyards, irrigation pools and bridges. The oasis at Niya preserves the ancient landscape. Here also have been found hundreds of 3rd and 4th century wooden accounting tablets at several settlements across the oasis. These texts are in the Kharosthi script native to today's Pakistan and Afghanistan. The texts are legal documents such as tax lists, and contracts containing detailed information pertaining to the administration of daily affairs.[81]

Additional excavations have unearthed tombs with mummies,[82] tools, ceramic works, painted pottery and other artistic artifacts. Such diversity was encouraged by the cultural contacts resulting from this area's position on the Silk Road.[83] Early Buddhist sculptures and murals excavated at Miran show artistic similarities to the traditions of Central Asia and North India[84] and stylistic aspects of paintings found there suggest that Miran had a direct connection with the West, specifically Rome and its provinces.[85]

See also

References

Citations

- Chen, Yaning, et al. "Regional climate change and its effects on river runoff in the Tarim Basin, China." Hydrological Processes 20.10 (2006): 2207-2216. (online Archived 2016-05-01 at the Wayback Machine 426 KB)

- Buono, Regina M.; Gunn, Elena López; McKay, Jennifer; Staddon, Chad (2019-10-31). Regulating Water Security in Unconventional Oil and Gas. Springer Nature. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-030-18342-4.

- The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge University Press. 1978. p. 69.

- Tian, Fei; Lu, Xinbian; Zheng, Songqing; Zhang, Hongfang; Rong, Yuanshuai; Yang, Debin; Liu, Naigui (2017-06-26). "Structure and Filling Characteristics of Paleokarst Reservoirs in the Northern Tarim Basin, Revealed by Outcrop, Core and Borehole Images". Open Geosciences. 9 (1): 266–280. Bibcode:2017OGeo....9...22T. doi:10.1515/geo-2017-0022. ISSN 2391-5447.

- Boliang, H., 1992, Petroleum Geology and Prospects of Tarim (Talimu) Basin, China, In Giant Oil and Gas Fields of the Decade, 1978-1988, AAPG Memoir 54, Halbouty, M.T., editor, Tulsa: American Association of Petroleum Geologists, ISBN 0891813330

- "Natural Gas Geochemistry in the Tarim Basin, China and Its Indication to Gas Filling History, by Tongwei Zhang, Quanyou Liu, Jinxing Dai, and Yongchun Tang, #10131". www.searchanddiscovery.net. 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-10-26.

- Karen Teo (January 4, 2005). "Doubts over Sinopec oil find in Tarim". thestandard.com.hk. Archived from the original on March 10, 2011.

- "Baker Hughes Signs Strategic Framework Agreement with PetroChina Tarim Oilfield Co". bakerhughes.com. June 10, 2010. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010.

- Li, Yan; Wang, Yu-Gang; Houghton, R. A.; Tang, Li-Song (2015). "Hidden carbon sink beneath desert". Geophysical Research Letters. 42 (14): 5880–5887. Bibcode:2015GeoRL..42.5880L. doi:10.1002/2015GL064222. ISSN 1944-8007. Lay summary – Inhabitat (2015-09-16).

- Wong, Edward (2009-07-12). "Rumbles on the Rim of China's Empire - NYTimes.com". www.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 2011-12-04. Retrieved 2009-07-13.

- "The mystery of China's celtic mummies". The Independent. London. August 28, 2006. Archived from the original on January 4, 2016. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- von Le Coq, Albert. (1913). Chotscho: Facsimile-Wiedergaben der Wichtigeren Funde der Ersten Königlich Preussischen Expedition nach Turfan in Ost-Turkistan Archived 2016-09-15 at the Wayback Machine. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), im Auftrage der Gernalverwaltung der Königlichen Museen aus Mitteln des Baessler-Institutes, Tafel 19 Archived 2016-09-15 at the Wayback Machine. (Accessed 3 September 2016).

- Gasparini, Mariachiara. "A Mathematic Expression of Art: Sino-Iranian and Uighur Textile Interactions and the Turfan Textile Collection in Berlin" Archived 2017-05-25 at the Wayback Machine", in Rudolf G. Wagner and Monica Juneja (eds), Transcultural Studies, Ruprecht-Karls Universität Heidelberg, No 1 (2014), pp 134-163. ISSN 2191-6411. See also endnote #32. (Accessed 3 September 2016.)

- Hansen, Valerie (2012), The Silk Road: A New History, Oxford University Press, p. 98, ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- Bailey, H.W. (1996) "Khotanese Saka Literature", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint edition), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 1230.

- Zhang Guang-da (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia Volume III: The crossroads of civilizations: AD 250 to 750. UNESCO. p. 283. ISBN 978-8120815407.

- Yu Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 13.

- C. Debaine-Francfort, A. Idriss (2001). Keriya, mémoires d'un fleuve. Archéologie et civilations des oasis du Taklamakan. Electricite de France. ISBN 978-2868050946.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- J. P. mallory. "Bronze Age Languages of the Tarim Basin" (PDF). Penn Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-09.

- Mallory, J. P. & Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. London. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-500-05101-6.

- Torday, Laszlo. (1997). Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. Durham: The Durham Academic Press, pp 80-81, ISBN 978-1-900838-03-0.

- Yü, Ying-shih. (1986). "Han Foreign Relations," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 377-462. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 377-388, 391, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Chang, Chun-shu. (2007). The Rise of the Chinese Empire: Volume II; Frontier, Immigration, & Empire in Han China, 130 B.C. – A.D. 157. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp 5-8 ISBN 978-0-472-11534-1.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola. (2002). Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 174-189, 196-198, 241-242 ISBN 978-0-521-77064-4.

- Yu Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, pp 13-14.

- Yu Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, pp 21-22.

- Ulrich Theobald. (26 November 2011). "Chinese History - Sai 塞 The Saka People or Soghdians Archived 2015-01-19 at the Wayback Machine." ChinaKnowledge.These records state that theyde. Accessed 2 September 2016.

- Ulrich Theobald. (16 October 2011). "City-states Along the Silk Road Archived 2006-05-13 at the Wayback Machine." ChinaKnowledge.de. Accessed 2 September 2016.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 37, 41–42. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Thierry 2005.

- "Les Saces", Iaroslav Lebedynsky, ISBN 2-87772-337-2, p. 59

- Liu Jianguo (2004). Distinguishing and Correcting the pre-Qin Forged Classics. Xi'an: Shaanxi People's Press. ISBN 7-224-05725-8. pp. 115–127

- Liu 2001a, p. 265.

- Jeong Su-il (17 July 2016). "Kucha Music". The Silk Road Encyclopedia. Seoul Selection. ISBN 9781624120763.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (2010). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-521-12433-1.

- Twitchett, Denis; Wechsler, Howard J. (1979). "Kao-tsung (reign 649-83) and the Empress Wu: The Inheritor and the Usurper". In Denis Twitchett; John Fairbank (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China Part I. Cambridge University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Skaff, Jonathan Karem (2009). Nicola Di Cosmo (ed.). Military Culture in Imperial China. Harvard University Press. pp. 183–185. ISBN 978-0-674-03109-8.

- Skaff, Jonathan Karam (2012). Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580-800. Oxford University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-19-973413-9.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 33–42. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- Loewe, Michael. (1986). "The Former Han Dynasty," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 103–222. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 197-198. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Yü, Ying-shih. (1986). "Han Foreign Relations," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 377-462. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 410-411. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Xavier Tremblay, "The Spread of Buddhism in Serindia: Buddhism Among Iranians, Tocharians and Turks before the 13th Century", in The Spread of Buddhism, eds Ann Heirman and Stephan Peter Bumbacker, Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2007, p. 77.

- Kuz'mina, Elena E. (2007). The Origin of the Indo Iranians. Edited by J.P. Mallory. Leiden, Boston: Brill, pp 381-382. ISBN 978-90-04-16054-5.

- Xue, Zongzheng (薛宗正). (1992). History of the Turks (突厥史). Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, p. 596-598. ISBN 978-7-5004-0432-3; OCLC 28622013

- Beckwith, Christopher. (1987). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp 36, 146. ISBN 0-691-05494-0.

- Wechsler, Howard J.; Twitchett, Dennis C. (1979). Denis C. Twitchett; John K. Fairbank, eds. The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part I. Cambridge University Press. pp. 225–227. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Scott Cameron Levi; Ron Sela (2010). Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 0-253-35385-8.

- Ahmad Hasan Dani; B. A. Litvinsky; Unesco (1 January 1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. pp. 283–. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- Emmerick, R. E. (2003) "Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1 (reprint edition) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 265.

- Emmerick, R. E. (2003) "Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1 (reprint edition) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 265-266.

- Bailey, H.W. (1996) "Khotanese Saka Literature", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint edition), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 1231-1235.

- Hansen, Valerie (2005). "The Tribute Trade with Khotan in Light of Materials Found at the Dunhuang Library Cave" (PDF). Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 19: 37–46. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04.

- Golden, Peter. B. (1990), "The Karakhanids and Early Islam", in Sinor, Denis (ed.), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 357, ISBN 978-0-521-2-4304-9

- Valerie Hansen (17 July 2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press. pp. 226–. ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- Trudy Ring; Robert M. Salkin; Sharon La Boda (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. pp. 457–. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6.

- James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- George Michell; John Gollings; Marika Vicziany; Yen Hu Tsui (2008). Kashgar: Oasis City on China's Old Silk Road. Frances Lincoln. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-0-7112-2913-6.

- Thum, Rian (6 August 2012). "Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism". The Journal of Asian Studies. 71 (3): 627–653. doi:10.1017/S0021911812000629. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- Johan Elverskog (6 June 2011). Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8122-0531-2.

- Anna Akasoy; Charles S. F. Burnett; Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim (2011). Islam and Tibet: Interactions Along the Musk Routes. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 295–. ISBN 978-0-7546-6956-2.

- Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- Takao Moriyasu (2004). Die Geschichte des uigurischen Manichäismus an der Seidenstrasse: Forschungen zu manichäischen Quellen und ihrem geschichtlichen Hintergrund. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 207–. ISBN 978-3-447-05068-5.

- "哈密回王简史-回王家族的初始". Archived from the original on 2009-06-01.

- Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb; Bernard Lewis; Johannes Hendrik Kramers; Charles Pellat; Joseph Schacht (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. p. 677.

- "n the seventeenth century Naqshbandi Sufis consolidated power over the southern Tarim basin" China and Islam - The Prophet, the Party, and Law, Cambridge University Press.

- Michell 1870, p. 2.

- Martin 1847, p. 21.

- Fisher 1852, p. 554.

- The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature, Volume 23 1852, p. 681.

- Millward 1998, p. 21.

- Mentelle, Edme (11 May 2018). "Géographie Mathématique, Physique et Politique de Toutes les Parties du Monde: Rédigée d'après ce qui a été publié d'exact et de nouveau par les géographes, les naturalistes, les voyageurs et les auteurs de statistique des nations les plus éclairées..." H. Tardieu – via Google Books.

- Mentelle, Edme (11 May 2018). "Géographie Mathématique, Physique et Politique de Toutes les Parties du Monde: Rédigée d'après ce qui a été publié d'exact et de nouveau par les géographes, les naturalistes, les voyageurs et les auteurs de statistique des nations les plus éclairées..." H. Tardieu – via Google Books.

- Millward 1998, p. 23.

- Bovingdon, Gardner (2010-08-06). The Uyghurs: Strangers in Their Own Land. p. 11. ISBN 9780231519410.

- Stanley W. Toops (15 March 2004). S. Frederick Starr (ed.). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. Routledge. pp. 254–255. ISBN 978-0765613189.

- Wong, Edward (18 November 2008). "The Dead Tell a Tale China Doesn't Care to Listen To". New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0231139243. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Carter Vaughn Findley (15 October 2004). The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press. pp. 242–. ISBN 978-0-19-988425-4.

- Khan, Razib (March 28, 2008). "Uyghurs are hybrids". Discover Magazine. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011.

- Khan, Razib (September 22, 2009). "Yes, Uyghurs are a new hybrid population". Discover Magazine. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015.

- "Archaeological GIS and Oasis Geography in the Tarim Basin". The Silk Road Foundation Newsletter. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- David W. Anthony, Tracking the Tarim Mummies, Archaeology, Volume 54 Number 2, March/April 2001

- "A Discussion of Sino-Western Cultural Contact and Exchange in the Second Millennium BC Based on Recent Archeological Discoveries". Archived from the original on 2007-07-14. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- "Silk Road Trade Routes". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 2011-11-08. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- "Ten Centuries of Art on the Silk Road". Archived from the original on 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

Sources

- Baumer, Christoph. 2000. Southern Silk Road: In the Footsteps of Sir Aurel Stein and Sven Hedin. Bangkok: White Orchid Books.

- Bellér-Hann, Ildikó (2008). Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880-1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. Brill. ISBN 978-9004166752.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation.

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Mallory, J.P. and Mair, Victor H. 2000. The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. London. ISBN 0-500-05101-1.

- Edme Mentelle; Malte Conrad Brun (dit Conrad) Malte-Brun; Pierre-Etienne Herbin de Halle (1804). Géographie mathématique, physique & politique de toutes les parties du monde, Volume 12 (in French). H. Tardieu. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804729338. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Stein, Aurel M. 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan, 2 vols. Clarendon Press. Oxford.

- Stein, Aurel M. 1921. Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, 5 vols. London & Oxford. Clarendon Press. Reprint: Delhi. Motilal Banarsidass. 1980.

- Stein Aurel M. 1928. Innermost Asia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia, Kan-su and Eastern Iran, 5 vols. Clarendon Press. Reprint: New Delhi. Cosmo Publications. 1981.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tarim Basin. |

- Downloadable article: "Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age" Li et al. BMC Biology 2010, 8:15.

- Silk Road Seattle - University of Washington (The Silk Road Seattle website contains many useful resources including a number of full-text historical works)

- The International Dunhuang Project

- Along the ancient silk routes: Central Asian art from the West Berlin State Museums, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material from the Tarim Basin