1916 Atlantic hurricane season

The 1916 Atlantic hurricane season ran through the summer and the first half of fall in 1916. The season is one of only two hurricane seasons where two major hurricanes were reported before the month of August, the other being the 2005 season.

| 1916 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 13, 1916 |

| Last system dissipated | November 15, 1916 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | "Texas" |

| • Maximum winds | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 932 mbar (hPa; 27.52 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 18 |

| Total storms | 15 |

| Hurricanes | 10 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 5 |

| Total fatalities | 107 total |

| Total damage | $33.3 million (1916 USD) |

| Related article | |

| |

Season summary

1916 was a fairly active season, especially for the time. Fifteen tropical cyclones formed during the course of the year. Ten hurricanes formed, and five of those were major hurricanes. A record nine storms made landfall in the United States during the season, though the record was broken in 2020.[1]

Systems

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 13 – May 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1004 mbar (hPa) |

On May 13, a tropical depression formed south of the Cuban coast. It quickly crossed the island and moved over the Straits of Florida. On May 14, it slowly strengthened to a minimal tropical storm, and it made landfall near Key Vaca, Florida with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h). It entered the Florida peninsula near Cape Sable, moving northward across the state. Gale-force winds were reported east of the center. It transitioned to an extratropical cyclone on May 16. Initially, the cyclone was not included in the Atlantic hurricane database.[2]

The tropical storm ended a significant drought in Florida, producing the state's first widespread rainfall event in several months.[3] Parched crops and vegetation were rejuvenated by the well-timed rains. Lakeland, Florida, recorded 1.16 in (29 mm) of rain in a 24-hour period.[4] Strong, albeit non-damaging winds, were felt across the Florida coasts, with a peak gust of 44 mph (71 km/h) documented in Jacksonville.[4][5] Moderate gales were produced by the storm's extratropical stages in the Mid-Atlantic states and New England.[2] Widespread rainfall in southwestern Maine and southeastern New Hampshire from the storm's remnants peaked at 6.72 in (171 mm) in Durham, Maine, and damaged roads.[6] The cost of damaged infrastructure in southwestern Maine was estimated at $150,000.[7]

Hurricane Two

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 28 – July 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min) 950 mbar (hPa) |

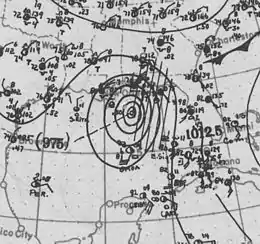

The Gulf Coast Hurricane of 1916

A tropical disturbance organized into a tropical storm on June 29 in the southwest Caribbean Sea. It moved to the north-northwest, brushing the coast of Honduras before strengthening into a hurricane on July 2. The hurricane continued to intensify, reaching major hurricane strength in the northern Gulf of Mexico on July 4. It made landfall near Gulfport, Mississippi with 120 mph (195 km/h) sustained winds on July 5. The damage was around $3 million with four deaths occurring. At the time, it was the earliest known major hurricane to make landfall in the U.S. in any season, but that record has since been broken by Hurricane Audrey.

In Florida, winds of 104 mph (167 km/h) was observed in Pensacola. People venturing outside were knocked down, while a few cars flipped over. Additionally, homes were unroofed, while chimneys and trees were toppled. At the aeronautic station, several hangars collapsed. Storm surge at Pensacola flooded an engine room at the municipal power plant, causing electrical outages. Further inland, heavy rainfall left severe crop damage in Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee. The storm left 34 deaths, 4 of which occurred in Florida, and $3 million in damage, including $1 million in Florida.

Hurricane Three

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 10 – July 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 980 mbar (hPa) |

The third tropical storm was first observed east of the Lesser Antilles on July 10. It tracked northwestward, crossing the islands before reaching hurricane strength north of Puerto Rico on July 15. The hurricane continued to the northwest, and reached a peak of 105 mph (170 km/h) on July 16.[2] Cool and dry air weakened it to a 70 mph (110 km/h) tropical storm when it hit New Bedford, Massachusetts on July 21. It caused little damage and no known deaths. Initially, the cyclone was recorded as a major hurricane, but it was subsequently downgraded by the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project.[2] Storm warnings were issued by the Weather Bureau for coastal stretches from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina to Eastport, Maine as the hurricane paralleled the coast offshore.[8] Ships destined for The Bahamas were held at the harbor in Miami, Florida.[9]

Hurricane Four

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 11 – July 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) 960 mbar (hPa) |

The Charleston Hurricane of 1916

Hurricane Four, which developed on July 11 north of the Bahamas, reached a peak intensity of 115 mph (185 km/h) winds on July 13. The hurricane moved ashore near Charleston, South Carolina as a strong Category 2 hurricane on July 14.[2] Seven deaths were reported, with $100,000 in damage. The heavy rains from this storm caused severe flooding of the French Broad River at Asheville, North Carolina.[10] The rains caused more damage due to subsequent flooding in Gaston, Lincoln and Cleveland Counties and further into South Carolina with three textile mills and their neighboring villages being either damaged beyond repair or destroyed. Damages in North Carolina were estimated at $15–$20 million with the loss of 80 lives. Mountain Island Mill, the oldest operating textile mill in the state and the Mountain Island village was completely destroyed and swept away by the flood waters.[11]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 4 – August 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) <996 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm formed in the southern Gulf of Mexico on August 4. On August 5, it struck the Mexican state of Tamaulipas with estimated winds of 60 mph (95 km/h). Tropical storm force winds affected southern Texas.[2]

Hurricane Six

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 12 – August 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min) 932 mbar (hPa) |

The Great Texas Hurricane of 1916

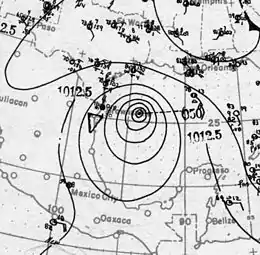

The fourth hurricane of the season was observed east of the Lesser Antilles on August 12. It passed through the islands, strengthening to a hurricane late on August 12 while crossing. On August 15, the hurricane hit Jamaica as a 90 mph (140 km/h) hurricane, and continued to the west-northwest through the Caribbean Sea and Yucatán Channel. On August 16, it became a major hurricane. It made landfall on Padre Island, Texas on August 18 as a 130 mph (215 km/h) hurricane. The hurricane caused 24 fatalities, with $1.8 million (1916 USD) in damage.

Hurricane Seven

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 21 – August 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) <997 mbar (hPa) |

Hurricane San Hipólito of 1916[lower-alpha 1]

The hurricane appeared over the northern Lesser Antilles on August 21. It tracked westward, becoming a hurricane and reaching a peak of 110 mph (175 km/h) winds before hitting Puerto Rico on August 22.[2] It was a small diameter hurricane that crossed Puerto Rico from Naguabo to Aguada.[12] From the Humacao region to the Aguadilla region suffered hurricane-force winds, with minor damages in the east and north of Puerto Rico. One death occurred and the damages were estimated at $1 million (1916 USD, $20.9 million 2010 USD).[12] In San Juan winds were measured at 92 mph and the pressure was 29.82 inches.[12] The worst damages occurred in Santurce.

It crossed Hispaniola on August 23, weakened to a tropical storm, and paralleled the north coast of Cuba. This fast moving storm turned northward, passing west of Miami, Florida on August 25. It dissipated on August 26.[2]

Hurricane Eight

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 27 – September 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 986 mbar (hPa) |

On August 27 a tropical storm was observed east of the Lesser Antilles. It strengthened into a hurricane that night before crossing Dominica with 80 mph (130 km/h) winds on August 28. This fast-moving hurricane moved through the Caribbean Sea, and it quickly weakened on August 30. On September 1 it made landfall on northern Belize as a tropical storm.[2]

The hurricane struck Dominica with little warning with winds exceeding 70 mph (115 km/h).[13][14] Fifty people were killed and two hundred homes were destroyed.[15] Many of the homes, bridges, and culverts were overtaken by swollen rivers that rose to unprecedented heights.[14] The storm was particularly destructive to the island's agriculture, including cocoa, coconut, lime, and rubber production. Over a hundred thousand barrels of limes were lost due to the downing of 83,198 lime trees and the loss of 23,100 others.[16] Many cocoa trees were destroyed.[17] Though these industries recovered quickly by the year's end,[16] the storm was ultimately part of a decade-long series of natural disasters and political events that eventually led to the demise of the island's cultivation economy by 1925.[18] Caution was advised for shipping in the vicinity of Jamaica on August 30 as the storm approached.[19] The passing storm brought showers and heavy surf to Jamaica, marking the second time in a fortnight that the island was affected by a tropical cyclone.[20] Torrential rains inflicted damage to some roads and cultivations.[21] At Mandeville, 12 in (300 mm) of rain fell due to the storm within a day.[22]

Tropical Storm Nine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 4 – September 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) <1010 mbar (hPa) |

The ninth tropical storm of the season formed over the eastern Bahamas on September 4. It tracked northward, and hit near the North Carolina/South Carolina border on September 6.

Storm warnings were issued by the Weather Bureau on September 5 for coastal areas between Savannah, Georgia, and Cape Hatteras; warnings were later extended north to the Virginia Capes.[23] Ahead of the storm, 1.40 in (36 mm) of rain fell in Wilmington, North Carolina.[24] Gale-force winds were produced inland following the storm's landfall.[23] Rainfall from the storm spread across the U.S. East Coast from North Carolina to Maine.[25]

Hurricane Ten

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 13 – September 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) <1000 mbar (hPa) |

The tenth tropical storm of the season, which was first observed on September 13 to the northeast of the Lesser Antilles, tracked westward before turning northward. It reached a peak of 85 mph (140 km/h) winds on September 18 before dissipating on September 24 in the northeast Atlantic.

Hurricane Eleven

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 17 – September 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min) <975 mbar (hPa) |

On September 17 the eleventh tropical storm was seen east of Barbados. It headed west-northward, strengthening into a hurricane on September 19 before passing north of the Lesser Antilles. The hurricane reached a peak of 120 mph (195 km/h) winds on September 22. It passed by Bermuda on September 24, and became extratropical on the same day.[2] The passing hurricane brought damaging winds of up to 75 mph (121 km/h) to Bermuda, resulting in downed trees and unroofed homes;[26][27] electrical and telephone services were also disrupted by the hurricane.[28] The damage toll was ₤30,000.[27]

Tropical Storm Twelve

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 2 – October 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm formed on October 2 and struck the Georgia coast on October 4.[2]

The Weather Bureau issued storm warnings from Fort Monroe to Savannah, Georgia.[29] Moderate gales occurred along the coasts of Georgia and South Carolina. The highest winds measured inland reached 33 mph (53 km/h) in Savannah, Georgia.[2]

Hurricane Thirteen

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 6 – October 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min) 963 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm appeared near the Windward Islands on October 6. It headed northwestward then northward, reaching hurricane strength in the eastern Caribbean. It approached the equivalent of Category 2 intensity as it passed over Saint Croix.[2] While accelerating to the northeast, the hurricane reached major hurricane strength, but cooler waters caused it to become extratropical on October 15.

Hurricane Fourteen

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 9 – October 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) 970 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression organized to a tropical storm on October 11 in the western Caribbean. It moved westward, reaching hurricane strength on the 13th before hitting the Yucatán Peninsula on the 15th as a 110 mph (175 km/h) hurricane. It weakened over land, and it emerged over the southern Gulf of Mexico as a tropical storm. It quickly re-strengthened to a strong Category 2 hurricane, hitting Pensacola on October 18.[2] This storm was a fast moving one so the damage was limited, but a ship sank offshore, killing 20 people. The remnants of this storm caused shipping losses on Lake Erie on the night of Friday, October 20, an event known as Black Friday that killed 49.[30]

Tropical Storm Fifteen

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 11 – November 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) |

The last storm of the season was first seen on November 11 in the Caribbean Sea. It tracked west-northwestward, hitting Honduras on the 13th. The storm turned northward, reaching peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) over the Yucatán Channel on November 14. It transitioned to an extratropical cyclone on November 15, and it passed over Key West.[2]

Notes

- This San Hipólito Hurricane of 1916 should not be confused with the 13 August 1835 San Hipólito Hurricane that also hit Puerto Rico. See page 27 of Eli D. Oquendo-Rodriguez's A Orillas del Mar Caribe: Boceto Histórico de la Playa de Ponce, desde sus primeros habitantes hasta principios del siglo XX. (Lajas, Puerto Rico: Editorial Akelarre. Centro de Estudios e Investigaciones del Sur Oeste (CIESCO). 2017. ISBN 978-1547284931).

References

- Masters, Jeff (August 5, 2020) [August 2, 2020]. "Tropical Storm Isaias: Updates from 'Eye on the Storm'". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Center for Environmental Communication. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- Hurricane Research Division. "HURDAT Meta-Data". NOAA. Archived from the original on March 16, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- Mitchell, Alexander J. (May 1916). "Florida Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. Jacksonville, Florida: Weather Bureau. 20 (5): 35. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- Bennett, Walter J. (May 15, 1916). "Storm Passes Tampa, Bringing Only Rain". Tampa Morning Tribune (23). Tampa, Florida. p. 2. Retrieved August 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bennett, Walter J. (May 15, 1916). "The Weather". The Tampa Daily Times (80). Tampa, Florida. p. 9. Retrieved August 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Smith, J. W. (May 1916). "New England Section" (PDF). Climatological Data. Jacksonville, Florida: Weather Bureau. 20 (5): 35. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- "Storm Damage in Maine". Fitchburg Daily Sentinel. 14 (12). Fitchburg, Massachusetts. p. 13. Retrieved August 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Storm Center Is Near The Coast". Fall River Evening News. Fall River, Massachusetts. July 21, 1916. p. 8. Retrieved March 21, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Schooners Are In Port Account Bahama Storm". Miami Daily Metropolis (186). Miami, Florida. Associated Press. July 18, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved March 21, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Western North Carolina Heritage. ASHEVILLE FLOOD of 1916. Archived August 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on June 23, 2008.

- Ragan, Robert (2001). The textile heritage of Gaston County, North Carolina, 1848–2000: one hundred mills and the men who built them. Charlotte, NC: Loftin & Company Printers, inc. p. 18. OCLC 51090391.

- Mújica-Baker, Frank. Huracanes y Tormentas que han afectado a Puerto Rico (PDF). Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, Agencia Estatal para el manejo de Emergencias y Administración de Desastres. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- Henry, Alfred J. (August 1916). "Forecasts and Warnings" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Boston, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society. 44 (8): 461–463. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..461H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<461:FAWFA>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- "Hurricane Kills 50 in Dominica Island". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. New York, New York. Associated Press. September 1, 1916. p. 3. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- "Hurricane Kills Fifty in Dominica". Lead Daily Call. Lead, South Dakota. Associated Press. September 1, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved March 28, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Dominica Recovering From a Hurricane". The World's Markets. 1. New York, New York: R. G. Dunn & Co. April 1917. p. 5. Retrieved March 28, 2020 – via Google Books.

- Barclay, Jenni; Wilkinson, Emily; White, Carole S.; Shelton, Clare; Forster, Johanna; Few, Roger; Lorenzoni, Irene; Woolhouse, George; Jowitt, Claire; Stone, Harriette; Honychurch, Lennox (April 12, 2019). "Historical Trajectories of Disaster Risk in Dominica" (PDF). International Journal of Disaster Risk Science. Springer. 10 (2): 149–165. doi:10.1007/s13753-019-0215-z. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- Green, Cecilia (1999). "A Recalcitrant Plantation Economy: Dominica, 1800–1946". NWIG: New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids. 73 (3/4): 43–71. doi:10.1163/13822373-90002577. ISSN 1382-2373. JSTOR 41849994.

- "A Disturbance In Caribbean East of Jamaica". The Daily Gleaner. 82 (201). Kingston, Jamaica. August 30, 1916. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- "The Hurricane". The Daily Gleaner. 82 (202). Kingston, Jamaica. August 31, 1916. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- "Damage Done". The Daily Gleaner. 82 (203). Kingston, Jamaica. September 1, 1916. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- "Flood at Mandeville". The Daily Gleaner. 82 (203). Kingston, Jamaica. September 1, 1916. pp. 1, 14 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- Bowie, Edward H. (September 1916). "Forecasts and Warnings, September, 1916" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Boston, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society. 44 (9): 519–521. Bibcode:1916MWRv...44..519B. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1916)44<519:FAWS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "High Water for Wrightsville". The Wilmington Dispatch. 28 (118). Wilmington, North Carolina. September 5, 1916. p. 8. Retrieved March 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Atlantic Coast Storm Over Lower Chesapeake". The Winston-Salem Journal. 28 (118). Wilmington, North Carolina. Associated Press. September 7, 1916. p. 4. Retrieved March 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane Sweeping Bermuda Island". The Philadelphia Inquirer. 175 (86). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. September 24, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 9, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Imperial and Foreign News Items". The Times (41282). London, England. September 26, 1916. p. 7. Retrieved February 9, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Bermuda Storm Swept". Chattanooga Daily Times. 47 (286). Chattanooga, Tennessee. September 25, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved February 9, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Gale in Atlantic is Off Georgia Coast". Tampa Morning Tribune (238). Tampa, Florida. Associated Press. October 4, 1916. p. 4. Retrieved August 8, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bowen, Dana Thomas, Lore of the Lakes, Freshwater Press, Cleveland, OH, 1940, p. 304, ISBN 9780912514123

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1916 Atlantic hurricane season. |