1919 Atlantic hurricane season

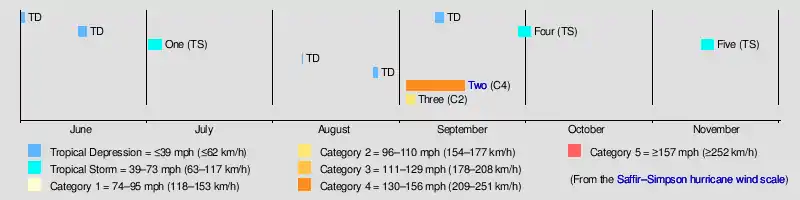

The 1919 Atlantic hurricane season was among the least active hurricane seasons in the Atlantic on record,[1] featuring only five tropical storms. Of those five tropical cyclones, two of them intensified into a hurricane, with one strengthening into a major hurricane (category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.) Two tropical depressions developed in the month of June, both of which caused negligible damage. A tropical storm in July brought minor damage to Pensacola, Florida, but devastated a fleet of ships. Another two tropical depressions formed in August, the first of which brought rainfall to the Lesser Antilles.

| 1919 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 1, 1919 |

| Last system dissipated | November 15, 1919 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | "Florida Keys" |

| • Maximum winds | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 927 mbar (hPa; 27.37 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 10 |

| Total storms | 5 |

| Hurricanes | 2 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 1 |

| Total fatalities | 828 |

| Total damage | $22 million (1919 USD) |

| Related article | |

| |

The most intense tropical cyclone of the season was the Florida Keys hurricane. Many deaths occurred after ships capsized in Bahamas, the Florida Keys, and Cuba. Strong winds left about $2 million in damage in Key West. After crossing the Gulf of Mexico, severe impact was reported in Texas, especially the Corpus Christi area. Overall, the hurricane caused 828 fatalities and $22 million in damage, $20 million of which was inflicted in Texas alone. Three other tropical cyclones developed in September, including two tropical storms and one tropical depression, all of which left negligible impact on land. The final tropical system of the season also did not affect land and became extratropical on November 15.

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 55.[1] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is tropical storm strength.[2]

Timeline

Systems

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 2 – July 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 995 mbar (hPa) |

Historical weather maps indicate a tropical wave in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico on July 2,[3] which developed into a tropical depression that day. Around 18:00 UTC, the depression strengthened into a tropical storm. Moving north-northwestward, it peaked with maximum sustained winds winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 995 mbar (29.4 inHg).[4] The storm remained very small in diameter "at all times."[5] At 11:00 UTC on July 4, the storm made landfall near Navarre, Florida at the same intensity. Early the next day, it weakened to a tropical depression, before dissipating several hours later.[4] In Pensacola, Florida, the auxiliary schooner Nautilus of the E. E. Saunders Fish Company's fleet was destroyed, resulting in $1,500 in damage. The schooner W.D. Hossack was abandoned by the crew, though this vessel was later salvaged by the schooner Bluefields and the tugboat Echo. Light damage to crops was also reported.[3]

Hurricane Two

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 2 – September 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min) 927 mbar (hPa) |

The Great Florida Keys Hurricane of 1919

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression on September 2, while located near Guadeloupe.[3][4] Early on September 3, the system became a tropical storm. It oscillated slightly in intensity during the next few days, while brushing Puerto Rico and north coast of Hispaniola. By September 5, the storm headed northward toward the southeastern Bahamas. The system crossed Mayaguana and began curving northwestward. Early on September 7, the storm strengthened into a Category 1 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale, while curving just north of due west. After intensifying into a Category 2 hurricane later that day, the hurricane struck Long Island and Exuma. Around 12:00 UTC on September 8, the storm strengthened into a Category 3 hurricane, shortly before striking Andros. After clearing the Bahamas, the hurricane strengthened into a Category 4 hurricane early the following day. It intensified further over the Straits of Florida and peaked with maximum sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 927 mbar (27.4 inHg) at 06:00 UTC on September 10. Hours later, the system made landfall in Dry Tortugas, Florida. The storm weakened while crossing the Gulf of Mexico and fell to Category 3 intensity around 12:00 UTC on September 12. However, early the following day, it re-strengthened into a Category 4 hurricane. While approaching Texas, the system began to weaken again, deteriorating to a Category 3 hurricane on September 14. Later that day, it made landfall in Kenedy County with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). The storm weakened while moving inland and dissipated near El Paso on September 16.[4]

Two schooners capsized in the Windward Islands due to the hurricane.[6] In the United States Virgin Islands, a sustained wind speed of 48 mph (77 km/h) was observed on Saint Thomas.[7] Strong winds lashed the Bahamas, destroying buildings on Eleuthera and demolishing houses on San Salvador Island.[6] The steamer Corydon sank in the Bahama Channel, resulting in 27 deaths.[8] In Florida, considerable damage was reported in the Miami area, though "nothing very serious resulted".[3] A tornado in Goulds damaged 19 buildings and destroyed six others.[7] On Key West, strong winds damaged brick-structured buildings, with "probably not a structure on the island" escaping impact. Additionally, large vessels that were firmly secured were torn loose from their mooring and beached. Overall, three people drowned and damage reached approximately $2 million. The Spanish steamship SS Valbanera sank offshore Havana, Cuba, presumably drowning all 488 passengers and crewmen. In Texas, storm surge and tidal waves resulted in severe damage. Some 23 blocks of homes were destroyed or swept away in Corpus Christi. In the city alone, 284 bodies were recovered and damage was conservatively estimated at $20 million. In Matagorda, Palacios, and Port Lavaca, wharves, fish houses, and small boats were significantly impacted. The docks and buildings in Port Aransas were swept away, with the exception of a school building.[3] Houses and crops were also leveled in Victoria. Overall, 310 deaths were reported in Texas.[9]

Hurricane Three

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 2 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) <977 mbar (hPa) |

On September 1, a southwest-northeast oriented stationary front was situated offshore the East Coast of the United States from east of The Carolinas to the south of Nova Scotia.[3] By the following day, the front spawned a tropical depression about 225 mi (360 km) southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.[3][4] The depression moved northeastward and detached from the stationary front.[3] Around 06:00 UTC on September 2, it strengthened into a tropical storm. The system intensified into a hurricane early on the following day. Later on September 3, the storm strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane and peaked with maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (155 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 977 mbar (28.9 inHg). Thereafter, the storm weakened to a Category 1 and a tropical storm on September 4, before becoming extratropical near Cape Breton Island later that day.[4] This system was first identified as a hurricane by Ivan Tannehill in 1938.[3]

Tropical Storm Four

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 29 – October 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) <1005 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical disturbance developed into a tropical depression at 00:00 UTC on September 29, while located about 115 mi (185 km) northeast of the Abaco Islands in the Bahamas.[3][5] Moving northwestward along the periphery of a high-pressure area,[5] the depression strengthened into a tropical storm later that day. After peaking with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,005 mbar (29.7 inHg), the storm curved west-northwestward while approaching the Southeastern United States. At 01:00 UTC on October 1, the system made landfall near St. Simons, Georgia. The cyclone weakened to a tropical depression by later that day. Moving westward, it dissipated over southeastern Alabama early on October 2.[4]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 11 – November 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) <1003 mbar (hPa) |

An extratropical low-pressure area formed east of Bermuda on November 10. The low moved southwestward and gradually acquired tropical characteristics.[3] By 00:00 UTC on November 11, it developed into a tropical storm, while located about 415 mi (670 km) south-southeast of Bermuda. Around that time, the storm peaked with maximum sustained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,003 mbar (29.6 inHg). Later on November 12, it curved northwestward. The storm then turned east-southeastward the following day. On November 14, the system weakened and curved northeastward. Around 12:00 UTC the next day, it became extratropical, with the remnants dissipating hours later.[4]

Tropical depressions

In addition to the five other tropical storms, there were five tropical cyclones that remained a tropical depression. The first depression formed from a low pressure area just offshore Belize on June 1. Moving northward, the storm dissipated over the southeastern Gulf of Mexico by the following day. Another tropical depression from non-tropical origin near Bermuda on June 15. After tracking generally southwestward for a few days, the depression became extratropical on June 18. The next tropical depression was reported in the vicinity of the Windward Islands on August 18. It brought "heavy weather" to Barbados, causing two ship to run aground. On August 25, a tropical depression developed near the northern Cape Verde islands, before dissipated on the next day. The final depression that remained below tropical storm status formed southeast of Bermuda on September 9. The storm strengthened while heading northwestward, but transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on September 12.[3]

References

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. February 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- David Levinson (August 20, 2008). 2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones. National Climatic Data Center (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- Christopher W. Landsea; et al. (December 2012). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- William P. Day (December 1921). Summary Of The Hurricanes Of 1919, 1920, and 1921 (PDF). Weather Bureau (Report). Washington, D.C.: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 658 and 659. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- "Two Schooners Lost With All On Board". The Lewiston Daily Sun. Miami, Florida. September 8, 1919. p. 35. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- Papers Supplementing The Discussion Of The West Indian Hurricane Of Sept. 6–14, 1919 (PDF). Weather Bureau (Report). Washington, D.C.: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. September 1919. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- "Captain and 26 Dead in Sinking of Steamer Corydon in Hurricane" (PDF). The New York Times. Miami, Florida. September 12, 1919. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- David M. Roth (April 8, 2010). Texas Hurricane History (PDF). Weather Prediction Center (Report). Camp Springs, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1919 Atlantic hurricane season. |