1923 Chicago mayoral election

In the Chicago mayoral election of 1923, Democrat William E. Dever defeated Republican Arthur C. Lueder and Socialist William A. Cunnea. Elections were held on April 3, the same day as aldermanic runoffs.

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Results by ward[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Elections in Illinois |

|---|

|

Nominations

Democratic primary

Ahead of 1923, the Democratic Party had long been divided.[2] Carter Harrison Jr. and Edward Fitzsimmons Dunne had once each led factions which held equal prominence to a faction led by Roger Charles Sullivan. However, by the end of the 1910s, Sullivan's wing of the Chicago Democratic Party had dwarfed theirs. By then, the blocs of Harrison and Dunne had effectively united as well.[2] When Sullivan died in 1920, George Brennan became the party leader. He sought to unify the Democratic Party factions.[2]

While he had been long discussed as a potential mayoral candidate for almost two decades, in 1923, a combination of conditions and events catapulted William E. Dever to the nomination.[2] In December 1922, a number of influential Chicago advocates for clean government had held a forum led by Mrs. Kellog Fairbank and Reverend Graham Taylor at the City Club of Chicago about the pending mayoral election which Clarence Darrow attended.[2][3] This led to the establishment of the Non-Partisan Citizens Mayoral Committee led by Mrs. Kellog Fairbank, which sought to lobby both parties to put forth truthful alternatives to the corrupt and demagogic mayor Thompson.[2][3] They decided that they would analyze prospective candidates and compile a shortlist of candidates they would be willing to back.[2] Brennan, who was unable to narrow out the field of prospective candidates to personally back, took an interest in these efforts, seeing them as an opportunity to help inform him in narrowing out the field.[2] The committee ultimately put forth a shortlist of seven prospective candidates they backed, including Judge William E. Dever.[2] Dever had also been championed as a potential candidate by a broad array of individuals, including the Municipal Voters' League's George Sikes, William L. O'Connell (a leader in the party's Harrison-Dunne bloc), and Progressive Republican Harold Ickes.[2][3] It was believed that Dever could unite the Democratic Party and serve as a clean and honest leader of the city's government.[2] Brennan, particularly impressed that Dever had backing from both members of the Harrison-Dunne faction and from reformers outside of the party, decided to take a closer look at him as a candidate.[2] Upon meeting with him, he found comradery and a positive working dynamic with Dever. He struck an arrangement under which, if elected mayor, he would allow Dever independence, but expected that Dever would, in turn, agree not utilize his patronage powers to build a political machine usurping Brennan's leadership of the party.[2] After finding no opposition to Dever as a candidate from within the party leadership, he announced the next day that Dever was the party-backed candidate for mayor.[2]

Before Dever had become the consensus candidate, among the individuals speculated as prospective candidates by the press was Anton Cermak.[3]

Brennan worked to ensure that Dever was unopposed in the Democratic primary.[3]

Despite Brennan pushing forth Dever's candidacy, the public generally did not view Dever to be a "machine" candidate.[4] The public generally perceived that reformist citizens organizations had advocated Dever to the Democratic party leaders.[4]

The Democratic primary was regarded as having had a large turnout, considering that there were uncontested races for mayor, City Treasurer and City Clerk.[5]

Republican primary

Due to his poor health there had been uncertainty as to whether two-term incumbent Republican William H. Thompson would run for reelection.[6] He was also seen as more vulnerable to being unseated by a strong Democratic opponent, as Thompson had severed ties with a number of key political allies (including Robert E. Crowe and Frederick Lundin).[6] One of the final factors in Thompson's decision not to seek reelection was a scandal involving campaign manager being implicated in shaking down vendors of school supplies for bribes and political contributions.[7] Thompson had bled middle class support over rumors of corruption in his administration, and had bled working-class voter over his support of Prohibition (which Chicago voters had locally opposed by a greater than 80% margin in a 1919 referendum).[8] Uneager to joust with Dever, nearly a week after Dever became the presumptive Democratic candidate, Thompson announced his decision not to run with only a month before the Republican primary.[2][6]

Businessman and federal postmaster Arthur C. Lueder, backed by the Brundage-McCormick/Tribune and Deneen blocs of the party, won the nomination in the subsequent open primary.[2][3][5] He was also backed by Robert E. Crowe.[5] Lueder ran on a "ticket", mutually being endorsed by and endorsing City Treasurer candidate John V. Healy and City Clerk candidate William H. Cruden, neither of whom were opposed in their primaries.[5]

Candidate Edward R. Litsinger, a member of the Cook County Board of Review,[9] had been backed by the William Randolph Hearst and Frederick Lundin blocs of the party, and was also the candidate supported by remaining members of Thompson's faction of the party.[5]

Arthur M. Millard was the President of the Masonic Bureau of Service and Employment.[5]

Judge of the Municipal Court of Chicago Bernard P. Barasa ran on a pro-liquor platform.[5]

Lueder won a greater margin of victory than even his own campaign had expected.[5]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Arthur C. Lueder | 128,704 | 42.76 | |

| Republican | Edward R. Litsinger | 74,560 | 24.77 | |

| Republican | Arthur M. Millard | 51,054 | 16.96 | |

| Republican | Bernard P. Barasa | 46,690 | 15.51 | |

| Turnout | 301,008 | 100.00 | ||

General election

.jpg.webp)

Both major party candidates campaigned as reformers.[2]

Factors harming the Republican Party's prospects included a divide among the party's ranks, the scandals that had characterized Thompson's administration, and tax increases made during Thompson's mayoralty.[5]

Dever was only the second resident of Edgewater to run for mayor, after only Nathaniel Sears, and consequentially would be the first Edgewater resident to serve as mayor.[15] Dever had a strong reputation for honesty, and was seen to be smart and well-spoken.[2] He was supported by many reformers and independents. Many went so far as to organize the Independent Dever League, a group created to act in support of Dever's campaign.[2] Dever won strong backing from progressive independents.[3]

The traction issue reemerged in this election. Lueder promised to "study" the possibility of municipal purchase of street railways.[2][3] Dever, on the other hand, was far more enthusiastic on the issue, proclaiming that the most critical task for the victor of the election would be to resolve problems with the city's public transit.[2][3] These problems included price increases and declining quality of service provided by the Chicago Surface Lines.[2] A long time advocate for municipal ownership, Dever believed that it would be ideal for the city to buy-out the Chicago Surface Lines once their franchise expired in 1927.[2] He also had hopes of possibly acquiring the Chicago Rapid Transit Company.[2] Socialist Cunnea campaigned for a 5-cent fare.[11]

Lueder offered a strong contrast to the incumbent Republican mayor, being dignified and soft-spoken, with a strong reputation of personal integrity.[2] Thompson did not campaign at all on behalf of Republican candidate Lueder.[2] Lueder had strong support from the business community.[3] Running a tidy campaign, positioning himself as a nonpolitical businessman, Lueder focused on securing the support of the Republican Party's factions.[3] He maintained his support from the Brundage-McCormick and Deneen factions and picked up the backing of key figures from the Thompson faction of the party despite Thompson's own refusal to back him.[3]

Lueder attempted to portray himself as an expert administrator.[16] Lueder argued that his experience in real estate and as postmaster had sufficiently prepared him for the administrative role of the mayoralty, asserting that it provided a more valuable experience than holding various minor elected posts.[3] He stated, "I believe what the people want is a businessman for mayor. I believe that want a man who will devote his time to his duties as mayor of Chicago, and not building up a political machine.[3]

Lueder refused to formally debate Dever, despite Dever's request for debates.[3] However, on numerous occasions they spoke at the same events.[3]

Eugene V. Debs actively campaigned for Socialist nominee William A. Cunnea.[17]

The campaign was largely uneventful, with little tenuous debate or controversy arising.[2][18] However, in the final stretch of the campaign, a level of anti-Catholic sentiment was vocalized by select segments of Chicago's population, who were unhappy at the prospect of Dever, as a Catholic, being mayor.[2][3][18][16] At the same time, some made an effort at the close of the election to draw a link between the Ku Klux Klan and the Republican campaign.[18] Outside of this last minute heightening of discourse in select corners, the campaign proved to be relatively tame.[18]

Early into the race the candidates ran close in the polls.[3] However, Dever took a strong lead in the race.[3] By the end of the race, gambling boss James Patrick O'Leary had assigned 1-7 betting odds in favor of a Dever victory.[2][3]

Endorsements

- Individuals

- Individuals

- Edward Fitzsimmons Dunne, former Governor of Illinois and former Mayor of Chicago[3]

- Margaret Haley[3]

- Carter Harrison Jr., former Mayor of Chicago[3]

- Harold L. Ickes[3]

- Mrs. Kellog Fairbank[3]

- Julia Lathrop[3]

- Mary McDowell[3]

- Charles E. Merriam, Republican Chicago mayoral nominee in 1911[3]

- Raymond Robins[3]

- Colonel A.A. Sprague[3]

- Graham Taylor[3]

- Newspapers

Results

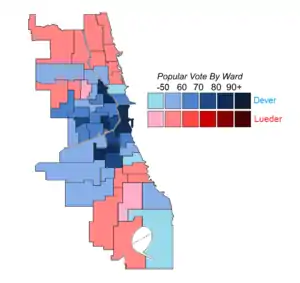

Dever won thirty-two of the city's fifty wards[2] (the 1923 election was the first after the city had redistricted itself from 35 to 50 wards).[3] His greatest share of votes was in the city's ten inner-city ethnic wards, located in traditional Democratic strongholds.[2] Lueder won the wards in traditionally-Republican areas on the edge of the city.[2] However, Dever made inroads with voters in these edge wards.[2] Dever also had made inroads among Black and Jewish voters.[2][3]

Dever received 83.47% of the Polish-American vote, while Lueder received 12.43% and Cunnea received 4.04%.[19]

Dever received more than 80% of the Italian American vote.[3]

Dever received 53% of the African American vote by some accounts.[3] This was a change from the typical voting pattern of Chicago African American voters, who regularly voted for the Republican Party.[20]

Dever received slightly less than half of the Swedish American and German American votes.[3]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | William E. Dever | 390,413 | 56.61 | |

| Republican | Arthur C. Lueder | 258,094 | 37.42 | |

| Socialist | William A. Cunnea | 41,186 | 5.97 | |

| Turnout | 689,693 | 100.00 | ||

References

- "Dever sweeps in by 103,748". The Chicago Daily Tribune. April 4, 1923. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- The Mayors: The Chicago Political Tradition, fourth edition by Paul M. Green, Melvin G. Holli SIU Press, Jan 10, 2013

- Schmidt, John R. (1989). "The Mayor Who Cleaned Up Chicago" A Political Biography of William E. Dever. DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press.

- Yarros, Victor S. (July 1926). "Sketches of American Mayors IV. William E. Dever of Chicago". National Municipal Review. XV (7).

- "Thompson Men Lose in Chicago Primaries, Lueder Winning the Nomination for Mayor". The New York Times. 28 February 1923. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Schottenhamel, George. “How Big Bill Thompson Won Control of Chicago.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, vol. 45, no. 1, 1952, pp. 30–49. JSTOR

- McClelland, Edward. "The Most Corrupt Public Official In Illinois History: William Hale Thompson". NBC Chicago. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- Cohen, Adam; Taylor, Elizabeth (2001). American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley - His Battle for Chicago and the Nation. Little, Brown. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7595-2427-9. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "The Daily News Almanac and Political Register for ..." Chicago Daily News Company. 1923. p. 785. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- "RaceID=690351". Our Campaigns. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- Headley, Kathleen J.; Krol, Tracy J. (October 19, 2015). Legendary Locals of Chicago Lawn and West Lawn. Arcadia Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 9781439654095.

- Illinois: A Descriptive and Historical Guide. US History Publishers. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-60354-012-4. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Headley, Kathleen J.; Krol, Tracy J. (2015). Legendary Locals of Chicago Lawn and West Lawn. Arcadia Publishing. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4396-5409-5. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "RADICALS: Active Debs". Time. 17 March 1923. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "Edgewater Teasers Vol. XVI No. 3 - FALL 2005". Edgewater History. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Bukowski, Douglas (1998). Big Bill Thompson, Chicago, and the Politics of Image. University of Illinois Press.

- "Debs-Cunnea Meeting". Newberry. La Parola del Popolo. March 3, 1923. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=897&dat=19230403&id=8aBaAAAAIBAJ&sjid=N08DAAAAIBAJ&pg=5749,3092278

- Kantowicz, Edward. “The Emergence of the Polish-Democratic Vote in Chicago.” Polish American Studies, vol. 29, no. 1/2, 1972, pp. 67–80. JSTOR, JSTOR

- "Crisis". 1923.

- "RaceID=123292". Our Campaigns. Retrieved December 6, 2018.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.png.webp)