1936 Spanish general election

Legislative elections were held in Spain on 16 February 1936. At stake were all 473 seats in the unicameral Cortes Generales. The winners of the 1936 elections were the Popular Front, a left-wing coalition of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE), Republican Left (Spain) (IR), Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC), Republican Union (UR), Communist Party of Spain (PCE), Acció Catalana (AC), and other parties. Their coalition commanded a narrow lead over the divided opposition in terms of the popular vote, but a significant lead over the main opposition party, Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (CEDA), in terms of seats. The election had been prompted by a collapse of a government led by Alejandro Lerroux, and his Radical Republican Party. Manuel Azaña would replace Manuel Portela Valladares, caretaker, as prime minister.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 473 seats of the Congress of Deputies 237 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 72.95% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

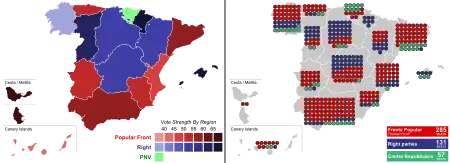

Left: vote strength result by region. Right: breakdown of seats in each region. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

American historian Stanley G. Payne, one of the most prominent foreign Hispanists, has written that the process was a major electoral fraud, with widespread violation of the laws and the constitution.[1] In line with Payne's point of view, in 2017 two Spanish Scholars, Manuel Álvarez Tardío and Roberto Villa García published the result of a research where they concluded that the 1936 elections were rigged.[2][3] This view has been criticised by Eduardo Calleja and Francisco Pérez, who question the charges of electoral irregularity. They argue that even if all of the charges were true, the Popular Front's legitimate vote would still have been a slight electoral majority.[4]

The elections were the last of three legislative elections held during the Spanish Second Republic, coming three years after the 1933 general election which had brought the first of Lerroux's governments to power. The uncontested victory of the political left in the elections of 1936 triggered a wave of Collectivisation, mainly in the south and west of the Iberian Peninsula, engaging up to three million people,[5] which has been identified as a key cause of the July coup.[6] The right-wing military coup initiated by Gens. Sanjurjo and Franco, the ensuing civil war, and the establishment of Franco's dictatorship ultimately brought about the end of parliamentary democracy in Spain until the 1977 general election.

Background

After the 1933 election, the Radical Republican Party (RRP) led a series of governments, with Alejandro Lerroux as a moderate Prime Minister. On 26 September 1934, the CEDA announced it would no longer support the RRP's minority government, which was replaced by a RRP cabinet, led by Lerroux once more, that included three members of the CEDA.[7] The concession of posts to CEDA prompted the Asturian miners' strike of 1934, which turned into an armed rebellion.[8] Some time later, Robles once again prompted a cabinet collapse, and five ministries of Lerroux's new government were conceded to CEDA, including Robles himself.[9] Since the 1933 elections, farm workers' wages had been halved, and the military purged of republican members and reformed; those loyal to Robles had been promoted.[10] However, since CEDA's entry into the government, no constitutional amendments were ever made; no budget was ever passed.[9]

In 1935, Manuel Azaña Díaz and Indalecio Prieto worked to unify the left and combat its extreme elements in what would become the Popular Front; this included staging of large, popular rallies,.[10] Lerroux's Radical government collapsed after two significant scandals, including the Straperlo affair. However, president Niceto Alcalá Zamora did not allow the CEDA to form a government, and called elections.[11] Zamora had become disenchanted with Robles's obvious desire to do away with the republic and establish a corporate state, and his air of pride. He was looking to strengthen a new center party in place of the Radicals, but the election system did not favour this.[12] Manuel Portela Valladares was thus chosen to form a caretaker government in the meantime. The Republic had, as its opponents pointed out, faced twenty-six separate government crises.[13] Portela failed to get the required support in the parliament to rule as a majority.[14] The government was dissolved on 4 January; the date for elections would be 16 February.[13]

As in the 1933 election, Spain was divided into multi-member constituencies; for example, Madrid was a single district electing 17 representatives. However, a voter could vote for fewer than that – in Madrid's case, 13. This favored coalitions, as in Madrid in 1933 when the Socialists won 13 seats and the right, with only 5,000 votes less, secured only the remaining four.[15]

Election

Vatican Fascism offered you work and brought hunger; it offered you peace and brought five thousands tombs; it offered you order and raised a gallows. The Popular Front offers no more and no less than it will bring: Bread, Peace and Liberty!

— One election poster.[16]

There was significant violence during the election campaign, most of which initiated by the political left, though a substantial minority was by the political right. In total, some thirty-seven people were killed in various incidents throughout the campaign, ten of which occurred on the election day itself.[17][18] Certain press restrictions were lifted. The political right repeatedly warned of the risk of a 'red flag' – communism – over Spain; the Radical Republican Party, led by Lerroux, concentrated on besmirching the Centre Party.[16] CEDA, which continued to be the main party of the political right, struggled to gain the support of the monarchists, but managed to. Posters, however, had a distinctly fascist appeal, showing leader Gil-Robles alongside various autocratic slogans and he allowed his followers to acclaim him with cries of "Jefe!" (Spanish for "Chief!") in an imitation of "Duce!" or "Führer!".[19][20] Whilst few campaign promises were made, a return to autocratic government was implied.[19] Funded by considerable donations from large landowners, industrialists and the Catholic Church – which had suffered under the previous Socialist administration – the Right printed millions of leaflets, promising a 'great Spain'.[21] In terms of manifesto, the Popular Front proposed going back to the sort of reforms its previous administration, including important agrarian reforms, and those to do with the treatment of strikes.[16] It would also release political prisoners, including those from the Asturian rebellion (though this provoked the right),[22] helping to secure the votes of the CNT and FAI, although as organisations they remained outside the growing Popular Front;[23] the Popular Front had the support of votes from anarchists.[24] The Communist Party campaigned under a series of revolutionary slogans; however, they were strongly supportive of the Popular Front government. "Vote Communist to save Spain from Marxism" was a Socialist joke at the time.[25] Devoid of strong areas of working class support, already taken by syndicalism and anarchism, they concentrated on their position within the Popular Front.[25] The election campaign was heated; the possibility of compromise had been destroyed by the left's Asturian rebellion and its cruel repression by the security forces. Both sides used apocalyptic language, declaring that if the other side won, civil war would follow.[26]

34,000 members of the Civil Guards and 17,000 Assault Guards enforced security on election day, many freed from their regular posts by the carabineros.[16] The balloting on the 16th of February ended with a draw between the left and right, with the center effectively obliterated. In six provinces left-wing groups apparently interfered with registrations or ballots, augmenting leftist results or invalidating rightist pluralities or majorities.[27] In Galicia, in north-west Spain, and orchestrated by the incumbent government; there also, in A Coruña, by the political left. The voting in Granada was forcibly (and unfairly) dominated by the government.[28] In some villages, the police stopped anyone not wearing a collar from voting. Wherever the Socialists were poorly organised, farm workers continued to vote how they were told by their bosses or caciques. Similarly, some right-wing voters were put off from voting in strongly socialist areas.[29] However, such instances were comparatively rare.[30] By the evening, it looked like the Popular Front might win and as a result in some cases crowds broke into prisons to free revolutionaries detained there.[24][31]

Outcome

Just under 10 million people voted,[24] with an abstention rate of 28 percent, a level of apathy higher than might be suggested by the ongoing political violence.[32] A small number of coerced voters and anarchists formed part of the abstainers.[32] The elections of 1936 were narrowly won by the Popular Front, with vastly smaller resources than the political right, who followed Nazi propaganda techniques.[11] The exact numbers of votes differ among historians; Brenan assigns the Popular Front 4,700,000 votes, the Right around 4,000,000 and the centre 450,000,[33] while Antony Beevor argues the Left won by just 150,000 votes.[34] Stanley Payne reports that, of the 9,864,763 votes cast, the Popular Front and its allies won 4,654,116 votes (47.2%), while the right and its allies won 4,503,505 votes (45.7%), however this was heavily divided between the right and the centre-right. The remaining 526,615 votes (5.4%) were won by the centre and Basque nationalists.[35] It was a comparatively narrow victory in terms of votes, but Paul Preston describes it as a 'triumph of power in the Cortes'[36] – the Popular Front won 267 deputies and the Right only 132, and the imbalance caused by the nature of Spain's electoral system since the 1932 election law came into force. The same system had benefited the political right in 1933.[33] However, Stanley Payne argues that the leftist victory may not have been legitimate; Payne says that in the evening of the day of the elections leftist mobs started to interfere in the balloting and in the registration of votes distorting the results; Payne also argues that President Zamora appointed Manuel Azaña Díaz as head of the new government following the Popular Front's early victory even though the election process was incomplete. As a result, the Popular Front was able to register its own victory at the polls and Payne alleges it manipulated its victory to gain extra seats it should not have won. According to Payne, this augmented the Popular Front's victory into one that gave them control of over two-thirds of the seats, allowing it to amend the constitution as it desired. Payne thus argues that the democratic process had ceased to exist.[37] Roberto García and Manuel Tardío also argue that the Popular Front manipulated the results,[38] though this has been contested by Eduardo Calleja and Francisco Pérez, who question the charges of electoral irregularity and argue that the Popular Front would still have won a slight electoral majority even if all of the charges were true.[39]

The political centre did badly. Lerroux's Radicals, incumbent until his government's collapse, were electorally devastated; many of their supporters had been pushed to the right by the increasing instability in Spain. Portela Valladares had formed the Centre Party, but had not had time to build it up.[33] Worried about the problems of a minority party losing out due to the electoral system, he made a pact with the right, but this was not enough to ensure success. Leaders of the centre, Lerroux, Cambó and Melquíades Álvarez, failed to win seats.[33] The Falangist party, under José Antonio Primo de Rivera received only 46,000 votes, a very small fraction of the total cast. This seemed to show little appetite for a takeover of that sort.[40] The allocation of seats between coalition members was a matter of agreement between them.[41] The official results (Spanish: escrutinio) were recorded on 20 February.[24] The Basque Party, who had not at the time of the election been part of the Popular Front, would go on to join it.[30] In 20 seats, no alliance or party had secured 40% of the vote; 17 were decided by a second vote on 3 March.[42] In these runoffs, the Popular Front won 8, the Basques 5, the Right 5 and the Centre 2.[43] In May, elections were reheld in two areas of Granada where the new government alleged there had been fraud; both seats were taken from the national Right victory in February by the Left.[43]

Because, unusually, the first round produced an outright majority of deputies elected on a single list of campaign pledges, the results were treated as granting an unprecedented mandate to the winning coalition: some socialists took to the streets to free political prisoners, without waiting for the government to do so officially; similarly, the caretaker government quickly resigned on the grounds that waiting a month for the parliamentary resumption was now unnecessary.[44] In the thirty-six hours following the election, sixteen people were killed (mostly by police officers attempting to maintain order or intervene in violent clashes) and thirty-nine were seriously injured, while fifty churches and seventy conservative political centres were attacked or set ablaze.[45] Almost immediately after the results were known, a group of monarchists asked Robles to lead a coup but he refused. He did, however, ask prime minister Manuel Portela Valladares to declare a state of war before the revolutionary masses rushed into the streets. Franco also approached Valladares to propose the declaration of martial law and calling out of the army. It has been claimed that this was not a coup attempt but more of a "police action" akin to Asturias, [46][47][29] Valladares resigned, even before a new government could be formed. However, the Popular Front, which had proved an effective election tool, did not translate into a Popular Front government.[48] Largo Caballero and other elements of the political left were not prepared to work with the republicans, although they did agree to support much of the proposed reforms. Manuel Azaña Díaz was called upon to form a government, but would shortly replace Zamora as president.[48] The right reacted as if radical communists had taken control, despite the new cabinet's moderate composition, abandoned the parliamentary option and began to conspire as to how to best overthrow the republic, rather than taking control of it.[36][49] The military coup in Spain was triggered by the so-called ‘Spanish Revolution’, a spontaneous popular wave of collectivisation and cooperativism, engaging up to three million people, which was ignited by the victory of the left in the general election of 1936, a wave described by historian James Woodcock as “the last and largest of the world’s major anarchist movements”.</ref> James Woodcock, Anarchism (1962), London: Penguin, 1970, 374)</ref> Ironically, this movement was overmingly non-violent.

Results

| Party | Abbr. | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Popular Front (Frente Popular) | FP | 3,750,900 | 39.63 | ||

| Left Front (Front d’Esquerres)[nb 1] | FE | 700,400 | 7.40 | ||

| Total Popular Front: | 4,451,300 | 47.03 | |||

| Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Right-wing Groups and right[nb 2] | CEDA-RE | 1,709,200 | 18.06 | ||

| Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Right-wing Groups and Radical Republican Party[nb 3] | CEDA-PRR | 943,400 | 9.97 | ||

| Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Right-wing Groups and centre[nb 4] | CEDA-PCNR | 584,300 | 6.17 | ||

| Front Català d'Ordre - Lliga Catalana | LR | 483,700 | 5.11 | ||

| Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Right-wing Groups and Progressive Republican Party[nb 5] | CEDA-PRP | 307,500 | 3.25 | ||

| Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Right-wing Groups and Conservative Republican Party[nb 6] | CEDA-PRC | 189,100 | 2.00 | ||

| Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Right-wing Groups and Liberal Democrat Republican Party[nb 7] | CEDA-PRLD | 150,900 | 1.59 | ||

| Spanish Agrarian Party (Partido Agrario Español)[nb 8] | PAE | 30,900 | 0.33 | ||

| Total National Bloc: | 4,375,800 | 46.48 | |||

| Party of the Democratic Centre (Partido del Centro Democrático) | PCD | 333,200 | 3.51 | ||

| Basque Nationalist Party (Euzko Alderdi Jeltzalea-Partido Nacionalista Vasco) | EAJ-PNV | 150,100 | 1.59 | ||

| Radical Republican Party (Partido Republicano Radical)[nb 9] | PRR | 124,700 | 1.32 | ||

| Conservative Republican Party (Partido Republicano Conservador)[nb 10] | PRC | 23,000 | 0.24 | ||

| Progressive Republican Party (Partido Republicano Progresista)[nb 11] | PRP | 10,500 | 0.11 | ||

| Falange Española de las J.O.N.S.[nb 12] | 6,800 | 0.07 | |||

| Total | 9,465,600 | 100 | |||

| Source: història electoral.com | |||||

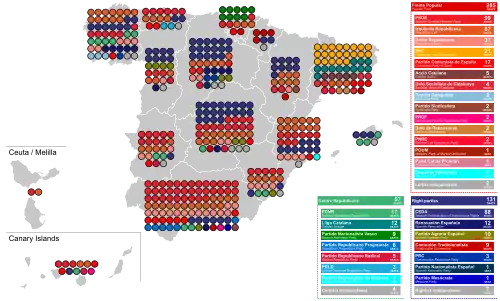

Seats

.svg.png.webp) .svg.png.webp) | |||||||||

| Affiliation | Party | Name in Spanish (* indicates Catalan, ** indicates Galician) | Abbr. | Seats (May) | Seats (Feb) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unknown | Payne[32] | ||||||||

| Popular Front | |||||||||

| Spanish Socialist Workers' Party | Partido Socialista Obrero Español | PSOE | 99 | 89 | 88 | ||||

| Republican Left | Izquierda Republicana | IR | 87 | 80 | 79 | ||||

| Republican Union | Unión Republicana | UR | 37 | 36 | 34 | ||||

| Republican Left of Catalonia | Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya* | ERC | 21 | 21 | 22 | ||||

| Communist Party of Spain | Partido Comunista de España | PCE | 17 | 15 | 14 | ||||

| Catalan Action | Acció Catalana* | 5 | 5 | 5 | |||||

| Socialist Union of Catalonia | Unió Socialista de Catalunya* | USC | 4 | 4 | 3 | ||||

| Galicianist Party | Partido Galeguista** | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| Syndicalist Party and Independent Syndicalist Party | Partido Sindicalista | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Democratic Federal Republican Party | PRD Fed. | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Union of Rabassaires | Unió de Rabassaires* | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| National Left Republican Party | PNRE | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Workers' Party of Marxist Unification | Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista | POUM | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Proletarian Catalan Party | Partit Català Proletari* | PCP | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Valencian Left | Esquerra Valenciana* | EV | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Independents (Payne: "Leftist independents") | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||

| Total Popular Front: | 285[50] | 267[50] | 263[nb 13] | ||||||

| Centre Republicans | |||||||||

| Party of the Democratic Centre | Partido del Centro Democrático | PCD | 17 | 20 | 21 | ||||

| Catalan League | Lliga Catalana* | 12 | 12 | 12 | |||||

| Basque Nationalist Party | Partido Nacionalista Vasco | PNV | 9 | 9 | 5 | ||||

| Progressive Republicans | Derecha Liberal Republicana | EAJ/DLR | 6 | 6 | 6 | ||||

| Radical Republican Party | Partido Republicano Radical | 5 | 8 | 9 | |||||

| Liberal Democrat Republican Party | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Mallorcan Regionalist Party | 1 | 1 | – | ||||||

| Independents | 4 | 3 | – | ||||||

| Total Centre: | 57 | 60 | 54 | ||||||

| Right | |||||||||

| Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right | Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas | CEDA | 88 | 97 | 101 | ||||

| National Bloc | Renovación Española | 12 | 13 | 13 | |||||

| Spanish Agrarian Party | Partido Agrario Español | PAE | 10 | 11 | 11 | ||||

| Traditionalist Communion | Comunión Tradicionalista | 9 | 12 | 15 | |||||

| Conservative Republican Party | Partido Republicano Conservador | PRC | 3 | 3 | 2 | ||||

| Independent monarchists | – | – | 2 | ||||||

| Spanish Nationalist Party | Partido Nacionalista Español | PNE | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Partido Mesócrata (Payne: "Catholic") | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Independents | 7 | 8 | 10 | ||||||

| Total Right: | 131 | 146 | 156 | ||||||

| Total: | 473 | ||||||||

References

Notes

- Running only in Catalonia

- Coalition of right-wing parties including CEDA in 30 constituencies

- Coalition of right-wing parties and the Radicals in 10 constituencies

- Coalition of right-wing parties and the centre in 6 constituencies

- Coalition of right-wing parties and the PRP in 4 constituencies in Andalusia

- Coalition of right-wing parties and the PRC in Lugo and A Coruña

- Running only in Oviedo

- Independent, separate Agrarian lists only in Burgos and Huelva

- Independent, separate Radical lists in Cáceres, Castellón, Ceuta, Málaga (prov.), Ourense, Santander, Tenerife, Las Palmas and Córdoba

- Running only in Soria

- Running only in Ciudad Real

- Running only in Oviedo, Sevilla, Toledo and Valladolid

- Payne (2006) gives a total of 262.

Citations

- Payne, Stanley G. (April 8, 2016). "24 horas - Stanley G. Payne: "Las elecciones del 36, durante la Republica, fueron un fraude"". rtve. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- Villa García & Álvarez Tardío 2017.

- Redondo, Javier. "El 'pucherazo' del 36" (in Spanish). El Mundo.

- Calleja, Eduardo González, and Francisco Sánchez Pérez. "Revisando el revisionismo. A propósito del libro 1936. Fraude y violencia en las elecciones del Frente Popular." Historia Contemporánea 3, no. 58 (2018).

- Gaston Leval, Social Reconstruction in Spain, London, 1938. Discussed in Woodcock, p. 373.

- see James Woodcock, Anarchism (1960), London: Penguin, 1970, pp. 365-375.

- Thomas (1961). p. 78.

- Thomas (1961). p. 80.

- Thomas (1961). p. 88.

- Preston (2006). p. 81.

- Preston (2006). pp. 82–83.

- Brenan (1950). p. 294.

- Thomas (1961). p. 89.

- Brenan (1950). pp. 294–295.

- Brenan (1950). p. 266.

- Thomas (1961). p. 92.

- Payne, S.G. and Palacios, J., 2014. Franco: A personal and political biography. University of Wisconsin Pres. p. 101

- Tardío, Manuel Álvarez. "The Impact of Political Violence During the Spanish General Election of 1936." Journal of Contemporary History 48, no. 3 (2013): 463-485.

- Brenan (1950). p. 289.

- Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Hachette UK, 2012.

- Beevor (2006). pp. 34–35.

- Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Hachette UK, 2012.

- Thomas (1961). pp. 91–2.

- Payne (2006). p. 175.

- Brenan (1950). p. 307.

- Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Hachette UK, 2012.

- Payne, S.G. and Palacios, J., 2014. Franco: A personal and political biography. University of Wisconsin Pres. p. 102

- Payne (2006). pp. 174–5.

- Brenan (1950). p. 300.

- Thomas (1961). p. 93.

- Payne, S.G. and Palacios, J., 2014. Franco: A personal and political biography. University of Wisconsin Pres. p. 102

- Payne (2006). p. 177.

- Brenan (1950). p. 298.

- Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Hachette UK, 2012.

- Payne, Stanley G. Spain's first democracy: the Second Republic, 1931-1936. Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1993, p.274

- Preston (2006). p. 83.

- Payne, S.G. and Palacios, J., 2014. Franco: A personal and political biography. University of Wisconsin Pres. p. 105

- García, Roberto Villa, and Manuel Álvarez Tardío. 1936. Fraude y violencia en las elecciones del Frente Popular. Espasa, 2017.

- Calleja, Eduardo González, and Francisco Sánchez Pérez. "Revisando el revisionismo. A propósito del libro 1936. Fraude y violencia en las elecciones del Frente Popular." Historia Contemporánea 3, no. 58 (2018).

- Beevor (2006). pp. 38–39

- Brenan (1950). p. 299.

- Thomas (1961). pp. 93–94.

- Thomas (1961). p. 100.

- Beevor (2006). p. 38

- Alvarez Tardio, Manuel. "Mobilization and political violence following the Spanish general elections of 1936." REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS POLITICOS 177 (2017): 147-179.

- Jensen, Geoffrey. Franco. Potomac Books, Inc., 2005, p.66

- Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Hachette UK, 2012.

- Brenan (1950). p. 301.

- Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Hachette UK, 2012.

- Lozano, Elecciones de 1936.

Further reading

- Beevor, Antony (2006). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-84832-1.

- Brenan, Gerald (1950). The Spanish Labyrinth: an account of the social and political background of the Spanish Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-04314-X.

- Ehinger, Paul H. "Die Wahlen in Spanien von 1936 und der Bürgerkrieg von 1936 bis 1939. Ein Literaturbericht," ['The 1936 elections in Spain and the civil war of 1936-39: a bibliographical essay'] Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Geschichte (1975) 25#3 pp 284–330, in German.

- Payne, Stanley G. (2006). The collapse of the Spanish Republic, 1933-1936: origins of the Civil War. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-11065-0.

- Preston, Paul (2006). The Spanish Civil War: Reaction, revolution and revenge (3 ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-723207-1.

- Thomas, Hugh (1961). The Spanish Civil War (1 ed.). London: Eyre and Spottiswoode.

- Vilanova, Mercedes. "Las elecciones republicanas de 1931 a 1936, preludio de una guerra y un exilo" Historia, Antropologia y Fuentes Orales (2006) Issue 35, pp 65–81.

- Villa García, Roberto. "The Failure of Electoral Modernization: The Elections of May 1936 in Granada," Journal of Contemporary History (2009) 44#3 pp. 401–429 in JSTOR

- Villa García, Roberto; Álvarez Tardío, Manuel (2017). 1936. Fraude y violencia en las elecciones del Frente Popular. Espasa. ISBN 978-8467049466.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)