35th Division (United Kingdom)

The 35th Infantry Division was an infantry division of the British Army, raised during World War I as part of General Kitchener's fourth New Army. Its infantry was originally composed of Bantams, that is soldiers who would otherwise be excluded from service due to their short stature. The division served on the Western Front from early 1916, and was disbanded in 1919.

| 35th Infantry Division | |

|---|---|

35th Division sign, second pattern,[1] used on vehicles.[2] The sign is made from seven '5's (=35).[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Active | April 1915 – June 1919 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Engagements | World War I |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Sir R. J. Pinney K.C.B. H. J. S. Landon C.B. C.M.G. G. M. Franks C.B. A.H. Marindin D.S.O. |

History

Formation and training

Originally authorised by the War Office for the Fifth New Army (K5) as the 42nd Division in December 1914, it was renumbered as the 35th Division of the Fourth New Army in April 1915 when the original Fourth New Army formations were repurposed to provide training and replacements for the first three Armies.[4] The Bantam experiment had begun in late 1914, with short but strong men recruited from labour-intensive industries. Sufficient numbers were raised for the infantry of a division and part of another (the 40th Division). Other units were not bantams; the artillery was raised locally, in Aberdeen (CLVII (157th) Brigade), Burnley and Accrington (CLVIII (158th) Brigade), Glasgow (CLIX (159th) Brigade) and West Ham (CLXIII (163rd) Brigade). By June 1915, the division had begun to congregate at Masham in Yorkshire and in August it was moved to Salisbury Plain. It had become apparent that a small number of the bantams were not physically strong enough for military duties, but instead of being dismissed, they were sent to the regimental depots.[5] In late 1915 the division was ordered to equip for a move to Egypt,[4] but this was cancelled, and between 29 and 31 January 1916 the division moved to France.[6]

1916

The division headquarters opened in France on 31 January, at Château de Nieppe 6.5 miles (10.5 km) east of Saint-Omer.[6] Part of XI Corps, on 5 February the division began to send officers and N.C.O.s to the front line to begin Trench warfare training and to move closer to the line in the Armentières sector. By mid February, in weather that was alternating rain and snow, infantry battalions and gunners from the 158th and 163rd Artillery Brigades were detached to front line divisions for further training, initially, the 17th Royal Scots and 17th West Yorks to 19th (Western) Division, and 17th and 18th Lancashire Fusiliers and 23rd Manchesters under the 38th (Welsh) Division.[lower-alpha 2] The first battlefield casualty of the division occurred on 20 February to a man of the 17th West Yorks.[8]

Aubers Ridge area

On 7 March the division took over a part of the front line near Festubert 4 miles (6.4 km) east of Béthune, with 104th Brigade relieving the 58th Brigade of the 19th Division, the 106th Brigade relieved the 57th Brigade and was still under order of the 19th Division, the 105th Brigade was still training under the 38th Division. The division's artillery was gradually withdrawn from its instructing units and was fully formed by mid-March. On 13 March the Germans detonated a mine under the 18th H.L.I., killing or wounding 60 men. The battalion held firm and the first bravery award to a man of the division is recorded (an M.C.).[9] The division's first trench raid was carried out by a 53 strong party from the 17th Lancashire Fusiliers, it was forced to retire as the Germans had been alerted and the allocation of only 30 rounds of ammunition per gun to the 157th and 158th Artillery Brigades was insufficient to support or adequately cut the wire. Remaining in the line, in late March the division 'side slipped' north east to a position opposite Aubers Ridge, relieving part of 8th Division, and by early April all three brigades had been in the line under 35th Divisional control. In mid April the division was moved again, this time south to the Neuve-Chapelle and Ferme Du Bois area, where it instructed parties from the 1st Australian Division in trench warfare after its arrival from Egypt.[10] During its time in this sector the division conducted numerous patrols in no-mans-land, and the artillery, which was reorganised on 14 May to have three identical brigades, each with one howitzer battery, exchanged at times intense fire with the Germans. On 28 May the division took over the Festubert sector from the 39th Division, requiring all three brigades in the line. On 30 May a well planned German artillery barrage destroyed, then isolated, part of the line occupied by the 15th Sherwood Foresters, enabling a German raiding party to carry off the wounded in that area as prisoners.[11] between 11 and 17 June the division (except for the artillery and trench mortars) was relieved by the 39th and 61st (2nd South Midland) Divisions, and moved west to the Busnes-Hinges area, 4.25 miles (6.84 km) north west of Béthune.[12]

The Somme

On 29 June the last of the dispersed artillery rejoined the division, and by 2 July was en route to Bouquemaison, 19.5 miles (31.4 km) north of Albert. The division's engineer and pioneers were attached to the 29th, 48th and 4th Divisions, and some of the division's officers reconnoitred the area north of Albert for a planned division attack there as part of the Somme battles. The division was now part of VIII Corps of Third Army. On 10 July these plans were cancelled, and the division was transferred to XIII Corps and marched south as part of the corps reserve, with the division headquarters at Morlancourt, 3.5 miles (5.6 km) south of Albert.[13] Except for a brief period, the division was not to be deployed as a whole during its time on the Somme. On 14 July the 105th was placed under orders of the 18th (Eastern) Division, and the 106th Brigade under the 9th (Scottish) Division in spite of the corps commander's reluctance for this type of deployment.[14]

Delville Wood

On the night of 16–17 July the 105th Brigade relieved parts of the 54th and 55th Brigades of 18th Division,[15] and by 18 July the 15th Sherwood Foresters had relieved the 7th Buffs in the trenches south of Trônes Wood, while part of the 16th Cheshires, some machine gunners and the pioneers took over Waterlot Farm on the Longueval-Guillemont road. By the afternoon of that day despite the heavy mud and artillery bombardment, they had beaten off an attack by some 300 Germans on the farm from Guillemont to the south east, and a battalion-sized attack from Delville Wood, using fire from carefully sited Vickers and Lewis guns to the west and east of the farm. The next day the positions east of the farm were heavily bombarded and pushed back, and when the battalion was withdrawn on 20 July it had suffered 35 officers and men killed, 194 wounded and 7 missing.[16]

It had been decided on 19 July that the brigade would attack from the positions held by the 15th Sherwood Foresters, to the east on the next day (20 July), however communications between the brigade headquarters and the battalions was difficult due to their dispersion and continual German artillery fire. The 15th Sherwood Foresters had been under gas and artillery attack, and only two companies were fit for action. Reinforced by only two companies from the 23rd Manchesters, the attack was reduced to an assault on two specific targets, Maltz Horn Farm and Arrowhead Copse, without observed artillery support due to the lay of the land.[17] Illuminated by the rising sun, both attacks by the 15th Sherwood Foresters were beaten back. However the French attacking on the right had made progress and so were left with an exposed flank, so a second attack by the 23rd Manchesters was made later in the morning. Although reaching the German trench, it was on a forward slope, facing the Germans, and intense machine gun fire forced a retirement. Losses to attacking companies were 375 killed wounded and missing. The brigade was relieved on 21 July by 104th Brigade and 8th Brigade of the 3rd Division.[18]

All three brigades were employed in the Delville Wood salient, either consolidating trenches or in the front line the 18th H.L.I. at Montauban quarry on 17 July, 19th D.L.I. at Longueval, the 104th Brigade opposite Maltz Horn Farm and Guillemont between 20 and 24 July, when it was heavily shelled after an attack on Guillemont by 30th Division. It was relieved by the 105th Brigade on 25 July. The 106th Brigade supported an advance east of Trônes Wood on 30–31 July.[19]

The infantry brigades were withdrawn from the front and billeted in villages on the Somme around 10 miles (16 km) west of Amiens. The artillery brigades remained to support further actions and were not withdrawn until mid-August. The infantry absorbed new drafts, however, these contained some of those rejected during the division's formation and others of the bantam type were no longer strong,[lower-alpha 3] there being a limited supply of this kind of man.[21]

The division returned to the Delville Wood salient on 9 August, in control of its own units, relieving parts of the 3rd and 24th Divisions. When not in the line the men were formed into working parties moving supplies and consolidating trenches. On 21 August a planned attack by the 105th Brigade towards Guillemont was stopped by heavy artillery fire initially believed to have been 'shorts' from the British, but later learned to have been Germans firing from the area of Le Sars. It was now that doubts were voiced about the quality of the new bantams. On 24 August the 17th Lancashire Fusiliers advanced the line some 300 yards (270 m) east towards Combles in line with the French 1st Division. On 30 August the infantry of the division was relieved by the 5th Division, the pioneers remained in the line for two more days.[22]

Arras

On 1 September the division was transferred to the Arras sector under IV Corps and relieved the 21st Division with all three brigades in the line. The pioneers arrived on 6 September and the artillery on 10 September.[23] Although supposedly resting after the Somme battles (as it was assumed were the Germans in this sector), there was patrolling in no-mans-land, trench raiding, with mixed results and an increase in the use of trench mortars by both sides. The effect of the trench mortaring was to continually damage, and in some cases destroy the trench system, despite being continually repaired, and as the weather worsened this repair became increasingly difficult and eventually could not be maintained.[24]

In the early hours of 26 November, a trench raid was planned by the 19th D.L.I., in preparation the manning was thinned out in the front line for the inevitable artillery and mortar retaliation. Instead, three areas were subject to intense trench mortaring and raids by the Germans themselves, those in the 105th Brigade area, the 17th Lancashire Fusiliers and coincidentally the 19th D.L.I.. In these raids numbers of the 17th Lancashire Fusiliers were thought to have swiftly surrendered, and a corporal and a sergeant of the 19th D.L.I. deserted their posts. The raid on the 105th Brigade area was not successful, the planned raid by the 19th D.L.I. took place, and while some men reached the Germans trench, most were stopped in no-mans-land by their own covering artillery barrage and their demoralisation due to the previous hours events. A raid the next night on the 15th Sherwood Foresters gained the Germans a prisoner. These events reinforced the complaints of commanding officers about the quality of the recent 'bantam' replacements.[25]

End of the bantam experiment

Between 1 and 5 December the division was relieved by the 9th (Scottish) Division, and was moved to an area 8 miles (13 km) east of Arras. Here it supplied working parties to the Army engineers, tunnelling companies and signals troops. Inspections were also carried out with a view to weeding out those unfit for duty or active service, and between 8 and 21 December 2,784 men were reported as unfit for infantry duty and marked down for eventual posting to the rear lines. They were to be replaced by men from disbanded yeomanry regiments and the cavalry training depot, a depot battalion was arranged in the division to train them for the front line. There remained a steadily dwindling number of the original, strong, bantams in the division for the rest of the war. The division was no longer to call itself a bantam division and the division sign of a red cockerel was replaced with the 'seven fives' sign.[26]

1917

The first of the replacements joined the division on 4 January, and numbered 1,350 by mid January.[27]

Hindenburg Line

%252C_1917.jpg.webp)

Between 5 and 17 February, the division was moved south by a series of marches to the Caix sector, 22 miles (35 km) east of Amiens, relieving the French 154th Division. On 23 February, attempting to disrupt the relief, the Germans mounted a raid on the 105th Brigade front, in retaliation the Germans received the fire from both the French and British division's artillery, as the French had not yet left the line. An early thaw made conditions muddy and difficult, with Trench foot appearing in the division.[lower-alpha 4][29]

The Germans conducted many trench raids on the division front, with the British high command believing this was a defensive cover for the planned retreat to the Hindenburg Line. In early March, the final batch of men unsuitable for infantry were sent to rear lines, and some additional men were classified as untrained and sent to the depot battalion for training. This left some battalions under-strength, with the 15th Cheshires having only 400 rifles. On 17 March, after supporting a French attack to the south and noting the lack of a response, the 17th West Yorkshires entered the German front line trench and reported it empty. By the end of the day the division had pushed forward 2 miles (3.2 km), but by late 18 March the division was ordered to halt. It was in converging line of advance, and the divisions either side (the 61st and 32nd) continued the advance with the division's 157th and 159th Artillery Brigades attached. The division was put to work salvaging and repairing road and rail communications in the area.[30]

By the end of March, the infantry was billeted along east of the Somme, and on 9 April the division received order to relieve the 61st (2nd South Midland) Division. By 12 April the relief had been completed under German bombardment with all battalions of the 104th and 106th brigades in the line reporting casualties. The line ran for approximately 4,000 yards (3,700 m) north west from Fresnoy-le-Petit, 3.5 miles (5.6 km) from Saint-Quentin. The division was to conduct patrolling and raiding in this area of the Hindenburg line until its relief on 19 May by the French 87th Division.[31]

Epéhy

On 22 May the division head-quarters opened in Péronne, with the front line occupied initially by the 104th and 106th brigades at Villers-Guislain by 26 May, on what was to become later in the year the Cambrai battlefield. The division remained here consolidating the trenches, which in some places were a series of disconnected outposts, and patrolling, until relieved by the 40th Division on 2 July.[32]

The Division moved 2 miles (3.2 km) south, and went into a line of approximately 8,000 yards (7,300 m) east of the village of Épehy, relieving the two brigades of the 2nd Cavalry Division on 6 July. The line in this sector was also largely made up of disconnected outposts, and the brigades began to connect and wire then into a continuous line. Seemingly in response to this work, the Germans mounted a number of trench raids, one of which lead to 92 casualties including a number in the 19th Northumberland Fusiliers who were helping to consolidate the trenches. The division was alerted to other trench raids by deserters, and on the night of 19–20 July these were beaten off by the 17th Royal Scots and 19th D.L.I., in spite of preparatory bombardment. Raiding and counter-raiding continued, especially around a section of trenches known as "the Birdcage" roughly in the centre of the division's line, and a small hill known as "the Knoll", 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km) to the south east, which gave the Germans an observation over the British lines.[33]

From the end of July planning was started for a raid which would gain control of the Knoll and lead to British views over the German lines and rear areas. It would take advantage of a build up of heavy artillery in the corps area (III Corps).[lower-alpha 5] On 17 August counter-battery and wire cutting bombardment began, and on 19 August, preceded by a rolling barrage across a 3,000 yards (2,700 m) front, the 15th Sherwood Foresters and 15th Cheshires advanced and took the now almost German obliterated trench. Casualties, including to the 16th Cheshires and 14th Gloucestershire in support were 52 killed, 166 wounded and 12 missing. Work began on a new front line and communication trenches, and the Germans began shelling the area. Early on 21 August, by which time the artillery support had been thinned out, the Germans made a determined attempt to recapture the trench, now held by the 14th Gloucestershires, using Flamethrowers in the attack. Initially forced back, time for a successful counterattack was gained by a severely burned 2nd Lieutenant Hardy Falconer Parsons, who held back the Germans using grenades. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for this action.[35]

In the early morning of 30 August, aided by a ground mist and the withdrawal of much of the Corps artillery to other areas, the Germans mounted an attack and retook the Knoll and other high ground in the area. Trench raiding by both sides continued until the division was relieved by the 55th (West Lancashire) Division on the night of 2–3 October.[36] Indicative of the losses sustained by the division, in mid September the 18th H.L.I. received a draft of 234 officers and men from the disbanded Glasgow Yeomanry (~25% of a nominal battalion strength), and was renamed as the 18th (Royal Glasgow Yeomanry) Battalion H.L.I.[37]

Ypres

At the start of October the infantry were billeted west of Arras, and the artillery east of Peronne, here they rested, refitted and trained. By the middle of October they had been moved by train, north to the rear area of the Ypres Salient, and by 16 October the 104th and 105th Brigades had relieved the 3rd Guards Brigade and 2nd Guards Brigade respectively opposite the Houthulst Forest, in the northern part of the salient, 6.5 miles (10.5 km) north east of Ypres. The division line was between a point on the Ypres-Staden railway approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) from Langemark, 2,100 yards (1,900 m) eastward on a north curving line. The artillery was in the Steenbek valley a short distance south west of Langemark. To the left of the division was the French 2nd Division and to the right the 34th Division. The weather and constant shelling had turned the area into a swampy morass of water filled shell holes which was difficult to traverse and made supply to the front difficult, but which had the benefit of muffling the effects of heavy shells.[38]

The division's first set piece attack since the Somme was to be made on 22 October as part of the general battle to remove the Germans from the high ground around Ypres. The division's attack was not on that ridge, but on the flatter ground some 2.75 miles (4.43 km) west of it. The 104th Brigade was to attack on the right with the 23rd Manchesters on the right flank in contact with the 101st Brigade of 34th Division and 17th Lancasters to their left. The 105th Brigade attacked with the 16th Cheshires on the right, and the 14th Cheshires on the left flank in contact with the French. The 106th Brigade was kept in reserve as it was still numerically weak.[39]

In the early morning of 22 October the attacking battalions formed up in the wet and cold weather in advance of the front line to escape the usual dawn bombardment. The objective for the day was a line some 750 yards (690 m) forward, and 500 yards (460 m) wider than the start line, to cover this the 18th Lancashire Fusiliers would advance into the gap left by the diverging 17th Lancashire Fusiliers and 23rd Manchesters on the right.[40] On the right the 23rd Manchesters, advancing behind a rolling barrage, starting at 05:35 hrs, which moved at 100 yards (91 m) every eight minutes, lost contact with the 34th Division as it had been prevented from taking a forward position due to heavy German bombardment. The advance wave reached its objective but came under heavy enfilading machine gun fire from the right and an overlooked set of huts, and so the remaining 50 unwounded men under command of a Company sergeant major were gradually withdrawn to the start line. The advancing wave in this battalion had suffered 204 killed, wounded and missing officers and men.[41] The 17th Lancashire Fusiliers advanced and three companies reached the objective by 06:45 hrs. However one company from the 18th Lancashire Fusiliers lost direction, and then advanced too far into the forest, and was subject to flanking fire from the right. Another company of the 18th Lancashire Fusiliers maintained contact with the 17th battalion, however, the Corps commander, on learning of this ordered two companies of the 20th Lancashire Fusiliers into the line on the right.[42]

The 16th Cheshires, in the centre left of the line, had difficulty keeping up with the barrage due to the state of the ground, and were held up by a number of strong points, however the left of their line reached the objective, with the remainder stopped by a block-house on the line. The 14th Gloucesters had advanced and reached the objective at 06:15 hrs. The division line was now on the objective line on the left, with an inward bulge about the block-house facing the 16th Cheshires, on the right part of the 17th Lancashires were at the objective, the rest of the line turned to face (approximately) north east, until the line reached the starting point of the 23rd Manchesters. Orders were issued that the ground captured was to be held with no new attacks to increase it.[43]

At 16:30 hrs the Germans launched a counter-attack around the block-house in front of the 16th Cheshires. The Germans broke through and for a time three companies of the 16th Cheshires and one of the 15th Sherwood Foresters were almost surrounded, and were compelled to withdraw to the start line. The 18th Lancashires were now in a thin salient and also fell back to the start line. The attack on the 14th Gloucestershires was broken up by artillery fire and a new right flank was formed by them refusing their flank and by a platoon of the 15th Sherwood Foresters assisting. An attack on the Lancashire battalions was weakened by artillery fire while it was forming up in the Houthulst Forest and it was beaten off.[44]

The weather and ground conditions were beginning to exhaust the men, and the assaulting battalions were relieved. Early on the morning of 23 October a raid by the 20th Lancashires on the huts that had fired on the advance the previous day was a partial success, capturing one post but then coming under retaliatory artillery fire. Later that morning a German attack at the junction of the 15th Cheshires and the French division on the left, this was stopped with artillery and rifle fire and 20 prisoners were taken. That night the centre of the line was pushed forwards some 200 yards (180 m) and consolidated. In the early days of November, during its relief by the 18th (Eastern) Division, the 106th Brigade came under heavy gas attack resulting in 138 casualties to the 19th D.L.I. on the night of 3–4 November. Between 18 and 29 October the division had suffered 368 killed, 1734 wounded and 462 missing, by the time the 17th West Yorks left the line they had been reduced a company strength. The artillery remained in the area as part of the Corps artillery group, supporting attacks by other divisions and on 6 and 7 November fired in support of operations around Passchendaele.[45]

The infantry were rested briefly around Poperinge and when they went back into the line on 16 November the 17th West Yorks had been replaced with the 4th Battalion (Extra Reserve) North Staffordshire Regiment. The division relieved the 58th (2/1st London) Division north of Poelkapelle, as part of II Corps between 1st Division on the right and 17th (Northern) Division on the left. The division remained in the line until the night of 8–9 December, suffering from the deteriorating weather as well as being subject to bombardment and attempted German trench raids. Relieved by the 58th (2/1st London) Division and rejoined by its artillery, the division would spend the remainder of the year near Poperinge, with details assisting the Army engineers in the area.[46]

1918

The division returned to the line on 8 January, relieving the 58th (2/1st London) Division east of Poelkapelle. The weather was cold and wet, and heavy rain on 15 and 16 January flooded a battery of the 159th Artillery Brigade, washing dead horses into its position. Initially on the left of the Corps' front, by 22 January the Division was holding the whole of the line with two brigades. The Germans attempted few trench raids, however one on the Kaiser's birthday (27 January), succeeded in taking three men as prisoners. In early February the division was reorganised into a three battalion per brigade structure, caused by manpower shortages, some political in origin.[47] The 20th Lancashire Fusiliers and 23rd Manchesters from the 104th Brigade, and the 16th Cheshires and 14th Gloucestershires from 105th Brigade were disbanded and the officers and men used to reinforce other battalions of the respective regiments (some of the 23rd Manchesters went to form the 12th Entrenching battalion. The division received the 12th Battalion H.L.I., joining the 160th Brigade and the 4th North Staffs. moved from there to the 105th Brigade, and the 19th D.L.I. going to the 104th Brigade. The division remained in this area, rejoined by the other divisions of II Corps in the line on 8 February. Trench raiding was carried out, with four separate raids carried out on the night of 28 February by the 105th Brigade. The results were mixed but included three prisoners, and the trench raiding continued up to 7 March. The division was relieved on 9 March by brigades from the 1st and 32nd Divisions, and went into camps north and north west of Poperinge.[48]

Spring Offensive

The Allies knew that the Germans would attempt an offensive with troops freed from the Eastern front, and as part of the defensive measures the division was put to work on the Army line in the region north of Ypres. On 21 March the division was put on alert to move at short notice, and on 23 March the division began to move south.

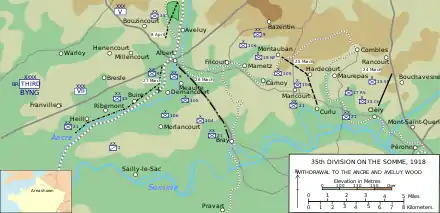

The Somme (1918)

The division now came under orders of VII Corps of the Fifth Army. The division was ordered to relieve the 21st Division then on the Cléry-Bouchavesnes ridge just north of the Somme, some 3 miles (4.8 km) north of Péronne. The first to arrive at Maricourt (7 miles (11 km) north west of Péronne) were elements of the 105th Brigade in the early evening of 23 March. By the early morning of 24 March the 21st division had been forced off the ridge and the brigade was placed under its orders. The 15th Cheshires and 15th Sherwood Foresters retook the high ground lost the previous day, with the Cheshires anchored on the right on the Somme but in doing so became separated with the Sherwood Foresters having an open left flank, and by the afternoon had suffered heavy casualties and were in danger of being overrun. They were extracted with the aid of the 17th Royal Scots, a pair of tanks and a Canadian Motor Machine Gun Battery and withdrew by the evening to the line between the villages of Curlu, Hardencourt and just to the east of Montauban-de-Picardy 1.5 miles (2.4 km) south-east to north-east of Maricourt[lower-alpha 6]. By this time General Franks had assumed command of the 9th (Scottish) and 21st divisions in this part of the line. The remainder of the division had arrived in the area by the evening when the division headquarters was ordered to move to the rear from Maricourt to Bray-sur-Somme 4 miles (6.4 km) to the south east. The exception was the artillery which was delayed, however the division's artillery commander was given command of the (remains of) 9th (Scottish) and 21st division's artillery and a number of Army artillery brigades deployed around Maricourt.[49]

Early on 25 March, the Germans found a weakly held part of the line south-east of Montauban-de-Picardy and forced back a detachment from the 12th H.L.I. back on to the 18th H.L.I in a valley between Carnoy and Montauban-de-Picardy. South of this action the remainder of the 12th H.L.I. resisted the German attacks and took 70 prisoners and 16 machine guns in counter attacks. South of Hardencourt the 15th Cheshires, 15th Sherwood Foresters and 17th Royal Scots held their line against German attacks but suffered considerable casualties from German artillery. Late in the morning the line was extended north of Montauban-de-Picardy, by two companies of the 19th N.F. and a late arriving company of the 17th Royal Scots, together with the 8th Hussars. In the afternoon the Germans attacked north of Hardencourt and after a series of attacks and counter attacks succeeded in pushing the line back so as to enfilade the British line to the south, which was subsequently pulled back. In these and previous engagements of the day the actions of Colonel W H Anderson earned him a (posthumous) Victoria Cross. In the evening orders were received by the division to retire to a line along the Albert - Bray-sur-Somme road, between 4 miles (6.4 km) and 5.5 miles (8.9 km) east of Maricourt due to German advances further north. During the retirement the opportunity was taken to restore units to their brigades.[50]

Division headquarters reopened at Sailly-Lauette 5 miles (8.0 km) south-east of Bray-sur-Somme early on 26 March. The line it commanded consisted of a composite brigade formed from the 21st Division in Bray, to the north, the 104th Brigade, then the 105th, in support was the 106th (with the 19th N.F. attached) with the 12th H.L.I. linking the 105th brigade and the 9th (Scottish) Division between Méaulte and Albert. Orders from VII Corps were that fighting for the line was not to become so involved that a retirement across the Ancre river was possible. The Germans began to probe the line in the mid morning, and by early afternoon the whole line was engaged with heavy supporting artillery fire. In accordance with the agreed plan the 21st Division composite brigade began to retire at 2pm, followed by the 104th Brigade at 2.45pm and the 105th at 3.15pm, passing through the 106th Brigade which was deployed east and north of Morlancourt 4 miles (6.4 km) east of Bray-sur-Somme. The 9th (Scottish) Division was already on the north bank of the Ancre. During this movement, orders were received from Fifth Army that no retirement was to occur unless tactically necessary. This appeared to contradict earlier orders, and General Franks and the Brigade commanders were of the opinion that the tired troops could not reoccupy the Bray-Albert line from where they were now, and the order was given to continue the withdrawal to the Ancre. This was complete by 7.30pm when the last of the rear guard (12th H.L.I.) crossed the Ancre.[51]

Orders had been received from VII Corps at 6.18pm to hold the Bray-Albert line and that any retirement was to be in the angle of the Somme and Ancre rivers. General Marindin prepared his 105th Brigade, who were short of ammunition and enjoying their first hot meal in days, while informing General Franks he thought the operation had little chance of success. VII Corps cancelled the order, but not before the 4th Staffords had re-crossed the Ancre and skirmished with some German working parties at Morlancourt before being recalled. In the early hours of 27 March General Marindin replaced General Franks as division commander as it was considered that he had misinterpreted the orders on 26 March[lower-alpha 7]. The division was now on the north bank of the Ancre, protected by a railway embankment, with outposts over the river, between Dernancourt and Ribemont-sur-Ancre, a south-east facing line 3 miles (4.8 km) long. That evening, after initial German probing was broken up by the division's artillery around Bresle 2 miles (3.2 km) north-east of the line of the Ancre, the 19th N.F. relieved the weakened South African Brigade on the division's left flank.[52] The 1st Cavalry Division held the remaining angle between the Somme and the Ancre.[53]

With the withdrawal of the 21st Division and the South Africans, the division was now flanked by Australians, the 3rd Division on the right flank and the 4th Division on the left flank. On 28 March the Germans strongly attacked the junction of the 19th N.F. and the 47th Australian Battalion behind Dernancourt, exploiting a road bridge piercing the embankment. As many machine guns as possible were deployed in this sector, with some on the southern side of the embankment, ammunition for which grew scarce due to a German bombardment 200 yards (180 m) to the rear hindering resupply. At 10:25am, with another attack apparently imminent, two companies of the 19th N.F. totalling only around 100 men pre-empted the next German assault.[lower-alpha 8] Assaults in the morning against the 104th Brigade around Treux 1 mile (1.6 km) east of Ribemont were broken up by artillery, machine gun and rifle fire. The Germans continued to shell the area for the rest of the day. After a relatively quiet two days for the division, the Australian Division closed up and relieved the 35th from its position on the Ancre. The division's artillery was placed under command of the 3rd Australian Division. in its eight days in the Somme area the division lost, killed wounded and missing, 90 officers and 1450 men.[57]

The division was dispersed and billeted a few miles behind the line of the Ancre while the Germans attacked toward Amiens. A German attack on 4 April on the Ancre involved the division's artillery supporting the Australians from around Bresel, and 106th Brigade who moved into reserve trenches between Bresel and Baisieux 3 miles (4.8 km) north of the Ancre. By 8 April the division had transferred to V Corps and moved North to Aveluy Wood 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Albert.[58]

Aveluy Wood

Aveluy Wood was a relatively undamaged wood with thick undergrowth on high ground on the west bank of the Ancre. The Germans had occupied the south east corner of the wood from 27-28 April, and the village of Aveluy approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) south-east of the division's line. The division's line south of the wood ran along high ground, which made supporting artillery fire into the area beyond difficult. The rear areas and billets in the villages of Martinsart and Bouzincourt were frequently shelled by long range German guns. On 16 April the division's artillery knocked down the Leaning Virgin on the Basilica in Albert.[59]

After some trench raiding in the difficult terrain of a still growing wood, the division and the 38th (Welsh) Division were tasked with taking the remainder of the wood and the wood and the valley to the south. For this operation the 104th Brigade was placed under orders of the 38th Division. In spite of support by additional divisional, corps and army artillery brigades the advances made by the 104th and 105th brigades were small, and cost the division 325 officers and men killed, wounded and missing. The division was relieved in the first few days of May, except for the artillery which remained in the line and was subject to a gas attack on the night of 10-11 May. Some of the infantry was detailed to work of the defensive Purple Line to the rear.[60]

The division returned to the Aveluy line on 19 and 20 May, relieving the 38th (Welsh) Division. Activity in the area had increased, with trench raids made by both sides and considerable artillery exchanges, including the use of gas. An attack was planned for 1 June to take that south-eastern part of the wood not in British hands, and a ravine to the south of the wood. The plan called for the artillery support of the 58th (2/1st) London Division (in the line to the south, the 18th (Western) Division to the north) and the release of gas and smoke, in the event the wind was unfavourable. In spite of the preparations the heavy undergrowth, concealing German machine gun positions and heavy artillery fire resulted in the early small gains of the 104th Brigade and the supporting two platoons of pioneers and 203rd Engineer company being driven back by the afternoon. Almost all of the pioneers became casualties retreating across the southern ravine, but the many of the wounded were recovered by the rest of the battalion. The attack cost the brigade 36 dead, 245 wounded and 75 missing, 77 prisoners were taken, with others killed by German shelling after reaching British lines. The division was subject to an increased level of German shelling for its remaining time at Aveluy Wood, when it was relieved by the 12th Division between 15 and 17 June.[61]

The division rested and retrained around Raincheval and Puchevillers, some 10 miles (16 km) east of Aveluy Wood, with working parties rotated out for work on the in-depth defence lines. An outbreak of influenza swept through the division and the whole army in France. At the end of the month the division entrained for Ypres sector.[62]

Ypres

The division transferred to XIX Corps (tactically under the French XVI Corps), and between 3 - 6 July relieved the French 71st Division in the Loker sector 6.5 miles (10.5 km) south-west of Ypres. The village of Loker was now on the front line after the German offensive Operation Georgette and was overlooked by the German held Kemmelberg some 6.5 miles (10.5 km) south-west of Ypres, which was itself on the front line, still in British hands. The division had orders, with the other divisions in the area not to give any ground, as this would endanger the British hold on Ypres. Operations were confined to trench raiding, by both sides, and artillery duels in which the division lost some guns. A small advance into German outposts was made on 20 July by the 12th H.L.I. and the 106th Brigade advanced its own to conform, but other planned attacks were called off due to wet weather. The division was relieved by the 30th Division on 9 August. The machine gun battalion, pioneers and a portion of the artillery assisted 30th Division in its attack and capture of the Dranoutre Ridge on 16 August. The division was transferred to II Corps on 1 September.[63]

Hundred days offensive

In 1918 the division participated in final allied offensive, reaching the River Dendre when the armistice ended the fighting in November 1918.[64]

Order of battle

Details from Baker, C. The 35th Division in 1914–1918.[4]

- 17th (Service) Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

- 18th (Service) Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

- 20th (Service) Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers (disbanded February 1918)

- 23rd (Service) Battalion, Manchester Regiment (disbanded February 1918)

- 19th (Service) (2nd County) Battalion, Durham Light Infantry (joined February 1918 from 106th Brigade)

- 104th Machine Gun Company, Machine Gun Corps (joined April 1916, left for division MG battalion February 1918)

- 104th Trench Mortar Battery (joined February 1916)

- 15th (Service) (1st Birkenhead) Battalion, Cheshire Regiment

- 16th (Service) (2nd Birkenhead) Battalion, Cheshire Regiment (disbanded February 1918)

- 14th (Service) Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment (disbanded February 1918)

- 15th (Service) Battalion, Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment)

- 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment (joined February 1918 from 106th Brigade)

- 105th Machine Gun Company, Machine Gun Corps (joined April 1916, left for division MG battalion February 1918)

- 105th Trench Mortar Battery (joined February 1916)

- 17th (Service) Battalion, Royal Scots (Lothian Regiment)

- 17th (Service) (2nd Leeds) Battalion, Prince of Wales's Own (West Yorkshire Regiment) (left November 1917)

- 19th (Service) (2nd County) Battalion, Durham Light Infantry (left February 1918 for 104th Brigade)

- 18th (Service) Battalion, Highland Light Infantry (renamed as the 18th (Royal Glasgow Yeomanry) Battalion, Highland Light Infantry in September 1917,[37])

- 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment (joined November 1917, left February 1918 for 105th Brigade)

- 12th (Service) Battalion, Highland Light Infantry (joined February 1918)

- 106th Machine Gun Company, Machine Gun Corps (joined April 1916, left for division MG battalion February 1918)

- 106th Trench Mortar Battery (joined February 1916)

Division Troops

- 19th (Service) Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers (Pioneers)

- 241st Machine Gun Company (joined July 1917, moved to Division MG battalion February 1918)

- 35th Battalion Machine Gun Corps (formed March 1918)

- C Squadron, Lancashire Hussars (left May 1916)

- 35th Divisional Cyclist Company, Army Cyclist Corps (left May 1916)

- 35th Divisional Train Army Service Corps

- 233rd, 234th, 235th and 236th Companies A.S.C.

- Royal Artillery

- 157th (Aberdeen) Brigade, R.F.A.

- 158th (Accrington and Burnley) Brigade R.F.A. (broken up February 1917)

- 159th (Glasgow) Brigade R.F.A.

- 163rd (West Ham) (Howitzer) Brigade R.F.A. (broken up September 1916)

- 131st Heavy Battery R.G.A. (left in March 1916)

- 35th Divisional Ammunition Column (British Empire League) R.F.A.

- V.35 Heavy Trench Mortar Battery R.F.A. (formed August 1916; left March 1918)

- X.35, Y.35 and Z.35 Medium Mortar Batteries R.F.A. (formed June 1916, Z broken up in February 1918, distributed to X and Y batteries)

- Royal Engineers

- 203rd, 204th, 205th (Cambridge) Field Companies

- 35th Divisional Signals Company

- Royal Army Medical Corps

- 105th, 106th, 107th Field Ambulances

- 75th Sanitary Section (left April 1917)

Awards

Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross was awarded to the following men of the division:[66]

- Lt Col William Herbert Anderson 12th Highland Light Infantry, 25 March 1918, Bois Favieres.

- 2nd Lt Hardy Falconer Parsons 14th Gloucestershire Regiment, 20/21 August 1917, Épehy.

Other awards

In addition to the two V.C.s, between 1916 and 1918 the officers and men of the division won the following (the list is incomplete, awards to the 15th Sherwood Foresters not being given as well as those unnamed in unit war diaries):[67]

| British Awards | |

|---|---|

| Companion of the Order of the Bath | 7 |

| Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George | 3 |

| Distinguished Service Order | 36 (including 2 bars) |

| Military Cross | 150 (including 5 bars) |

| Distinguished Conduct Medal | 44 |

| Military Medal | 328 (including 8 bars) |

| Meritorious Service Medal | 20 |

| French Awards | |

| Légion d'Honneur | 2 |

| Médaille militaire | 2 |

| Croix de Guerre | 20 |

| Belgian Awards | |

| Officier de l'Ordre de la Couronne | 3 |

| Croix de Guerre | 11 |

Commanders

The following officers commanded the division:

- Major General Reginald John Pinney KCB, from 4 July 1915[68]

- Major General H.J.S. Landon CB CMG, from 23 September 1916[69]

- Major General George McKenzie Franks CB, from 6 July 1917[70]

- Major General A.H. Marindin CB DSO, from 27 March 1918[71]

Notes

- An alternative, with the curve of the '5s' facing outwards was also used.[2] The sign was worn on uniforms after the armistice, black on a red background.[3]

- In addition to his normal kit, each infantryman was required to carry two sandbags to stand on while on the firing step, as the parapet of the trench or breastwork was not to be lowered.[7]

- These replacements were described in one after-action report by the Commander of 105th Brigade as "...either half-grown lads or degenerates".[20]

- A wounded stretcher-bearer had his uniform weighed at an aid post, and it was found to have 90 pounds (41 kg) of mud and water on it.[28]

- In addition to division's, and others, field guns, this included 60-pounder, 6-inch, 8-inch and 9.2-inch guns, and was the equivalent of eight Artillery Brigades.[34]

- By this time the villages in this area were only identifiable by bricks and other debris on the ground.

- The later inquiry was to find no fault with General Franks' conduct.

- The division history claims the Germans were driven back into Denancourt,[54] the official history that the German attack was stopped,[55] an Australian history that the 19th N.F. was quickly halted by machinegun fire from Dernancourt.[56]

References

- Davson (2003), p. 82.

- Chappell (1986), p. 19.

- Hibberd (2016), p. 41.

- Baker, Chris. "35th Division". The Long, Long Trail. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- Davson (2003), pp. 1–7.

- Davson (2003), p. 8.

- Davson (2003), p. 9 footnote.

- Davson (2003), p. 9.

- Davson (2003), pp. 12–13.

- Davson (2003), pp. 14–17.

- Davson (2003), pp. 18–20.

- Davson (2003), p. 21.

- Davson (2003), pp. 27–28.

- Davson (2003), pp. 30–31.

- Nichols (2003), p. 71.

- Davson (2003), pp. 31–33.

- Davson (2003), p. 34.

- Davson (2003), pp. 34–36.

- Davson (2003), pp. 36–41.

- Davson (2003), p. 48.

- Davson (2003), pp. 41–46.

- Davson (2003), pp. 46–52.

- Davson (2003), pp. 56–58.

- Davson (2003), pp. 59–73.

- Davson (2003), pp. 74–80.

- Davson (2003), pp. 81–82.

- Davson (2003), p. 85.

- Davson (2003), p. 89 footnote.

- Davson (2003), pp. 87–89.

- Davson (2003), pp. 92–94.

- Davson (2003), pp. 101–116.

- Davson (2003), pp. 118–125.

- Davson (2003), pp. 126–132.

- Davson (2003), pp. 136 & footnote, 144.

- Davson (2003), pp. 134–141.

- Davson (2003), pp. 142–154.

- Davson (2003), p. 152.

- Davson (2003), pp. 157–161.

- Davson (2003), p. 160.

- Davson (2003), pp. 160 footnote, 161.

- Davson (2003), pp. 161–162.

- Davson (2003), pp. 162–163.

- Davson (2003), pp. 163–164.

- Davson (2003), pp. 164–166.

- Davson (2003), pp. 166–172.

- Davson (2003), pp. 172–178.

- Hart (2009), pp. 28–29.

- Davson (2003), pp. 180–190.

- Davson (2003), pp. 192–198.

- Davson (2003), pp. 198–204.

- Davson (2003), pp. 205–209.

- Davson (2003), pp. 209–213.

- Edmonds, 2003 & Sketch 4.

- Davson (2003), pp. 214-215.

- Edmonds (2003), p. 54.

- Carlyon 2006, p. 207.

- Davson (2003), pp. 213–217.

- Davson (2003), pp. 217–219.

- Davson (2003), pp. 221–223.

- Davson (2003), pp. 221–227.

- Davson (2003), pp. 228–235.

- Davson (2003), pp. 235–238.

- Davson (2003), pp. 238–247.

- Davson (2003), pp. 193–297.

- Davson (2003), pp. 295–296.

- Davson (2003), pp. 298.

- Davson (2003), pp. 298–304.

- Davson (2003), p. 4.

- Davson (2003), p. 64.

- Davson (2003), p. 127.

- Davson (2003), p. 212.

Bibliography

- Chappell, Mike (1986). British Battle Insignia (1). 1914-1918. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85045-727-8.

- Davson, H. M. (2003) [1926]. The History of the 35th Division in the Great War (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Sifton Praed & Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84342-643-1.

- Deayton, Craig (2011). Battle Scarred: The 47th Battalion in the First World War. Newport, New South Wales: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9870574-0-2.

- Edmonds, James E (2019). Military Operations France & Belgium 1918 Volume 2. Uckfield: The Naval & Military Press. ISBN 9781845747268.

- Hart, Peter (2009). 1918. A Very British Victory (2nd ed.). London: Orion Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-75382-689-8.

- Hibberd, Mike (2016). Infantry Divisions, Identification Schemes 1917 (1st ed.). Wokingham: The Military History Society.

- Nichols, Capt. G. H. F. (2003) [1922]. The 18th Division in the Great War (Naval & Military Press ed.). Edinburgh & London: William Blackwood and Sons. ISBN 978-1-84342-866-4.

External links

- "35th Division". 1914-1918.net.