A Beautiful Mind (film)

A Beautiful Mind is a 2001 American biographical drama film based on the life of the American mathematician John Nash, a Nobel Laureate in Economics and Abel Prize winner. The film was directed by Ron Howard, from a screenplay written by Akiva Goldsman. It was inspired by the bestselling, Pulitzer Prize-nominated 1997 book of the same name by Sylvia Nasar. The film stars Russell Crowe, along with Ed Harris, Jennifer Connelly, Paul Bettany, Adam Goldberg, Judd Hirsch, Josh Lucas, Anthony Rapp, and Christopher Plummer in supporting roles. The story begins in Nash's days as a graduate student at Princeton University. Early in the film, Nash begins to develop paranoid schizophrenia and endures delusional episodes while watching the burden his condition brings on his wife Alicia and friends.

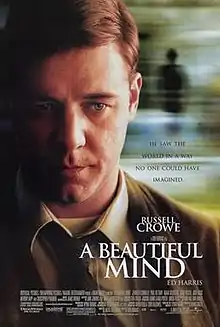

| A Beautiful Mind | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ron Howard |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by | Akiva Goldsman |

| Based on | A Beautiful Mind by Sylvia Nasar |

| Starring | |

| Music by | James Horner |

| Cinematography | Roger Deakins |

| Edited by | |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 135 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $58 million[2] |

| Box office | $313 million[2] |

The film opened in the United States cinemas on December 21, 2001. It went on to gross over $313 million worldwide and won four Academy Awards, for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Supporting Actress. It was also nominated for Best Actor, Best Film Editing, Best Makeup, and Best Original Score.

Plot

In 1947, John Nash arrives at Princeton University as co-recipient, with Martin Hansen, of the Carnegie Scholarship for mathematics. He meets fellow math and science graduate students Sol, Ainsley, and Bender, as well as his roommate Charles Herman, a literature student. Determined to publish his own original idea, Nash is inspired when he and his classmates discuss how to approach a group of women at a bar. Hansen quotes Adam Smith and advocates "every man for himself", but Nash argues that a cooperative approach would lead to better chances of success, and develops a new concept of governing dynamics. He publishes an article on his theory, earning him an appointment at MIT where he chooses Sol and Bender over Hansen to join him.

In 1953, Nash is invited to the Pentagon to crack encrypted enemy telecommunications, which he manages to decipher mentally. Bored with his regular duties at MIT, including teaching, he is recruited by the mysterious William Parcher of the United States Department of Defense with a classified assignment: to look for hidden patterns in magazines and newspapers to thwart a Soviet plot. Nash becomes increasingly obsessive in his search for these patterns, delivering his results to a secret mailbox, and comes to believe he is being followed.

One of his students, Alicia Larde, asks him to dinner, and they fall in love. On a return visit to Princeton, Nash runs into Charles and his niece, Marcee. With Charles' encouragement, he proposes to Alicia and they marry. Nash fears for his life after surviving a shootout between Parcher and Soviet agents, and learns Alicia is pregnant, but Parcher forces him to continue his assignment. While delivering a guest lecture at Harvard University, Nash tries to flee from people he thinks are Soviet agents, led by psychiatrist Dr. Rosen, but is forcibly sedated and committed to a psychiatric facility.

Dr. Rosen tells Alicia that Nash has schizophrenia and that Charles, Marcee, and Parcher exist only in his imagination. Alicia backs up the doctor, telling Nash that no "William Parcher" is in the Defense Department and takes out the unopened documents he delivered to the secret mailbox. Nash is given a course of insulin shock therapy and eventually released. Frustrated with the side effects of his antipsychotic medication, he secretly stops taking it and starts seeing Parcher and Charles again.

In 1956, Alicia discovers Nash has resumed his "assignment" in a shed near their home. Realizing he has relapsed, Alicia rushes to the house to find Nash had left their infant son in the running bathtub, believing "Charles" was watching the baby. Alicia calls Dr. Rosen, but Nash accidentally knocks her and the baby to the ground, believing he's fighting Parcher. As Alicia flees with the baby, Nash stops her car and tells her he realizes that "Marcee" isn't real because she doesn't age, finally accepting that Parcher and other figures are hallucinations. Against Dr. Rosen's advice, Nash chooses not to restart his medication, believing he can deal with his symptoms himself, and Alicia decides to stay and support him.

Nash returns to Princeton, approaching his old rival Hansen, now head of the mathematics department, who allows him to work out of the library and audit classes. Over the next two decades, Nash learns to ignore his hallucinations and, by the late 1970s, is allowed to teach again. In 1994, Nash wins the Nobel Prize for his revolutionary work on game theory, and is honored by his fellow professors. At the ceremony, he dedicates the prize to his wife. As Nash, Alicia, and their son leave the auditorium in Stockholm, Nash sees Charles, Marcee, and Parcher watching him, but looks at them only briefly before departing.

Cast

- Russell Crowe as John Nash

- Ed Harris as William Parcher

- Jennifer Connelly as Alicia Nash

- Christopher Plummer as Dr. Rosen

- Paul Bettany as Charles Herman

- Adam Goldberg as Richard Sol

- Josh Lucas as Martin Hansen

- Anthony Rapp as Bender

- Jason Gray-Stanford as Ainsley Neilson

- Judd Hirsch as Helinger

- Austin Pendleton as Thomas King

- Vivien Cardone as Marcee Herman

- Killian, Christian, and Daniel Coffinet-Crean as Baby

Production

Development

After producer Brian Grazer first read an excerpt of Sylvia Nasar's book A Beautiful Mind in Vanity Fair magazine, he immediately purchased the rights to the film. He eventually brought the project to director Ron Howard, who had scheduling conflicts and was forced to pass. Grazer later said that many A-list directors were calling with their point of view on the project. He eventually focused on a particular director, who coincidentally was available only when Howard was also available. Grazer chose Howard.[3]

Grazer met with a number of screenwriters, mostly consisting of "serious dramatists", but he chose Akiva Goldsman because of his strong passion and desire for the project. Goldsman's creative take on the project was to avoid having viewers understand they are viewing an alternative reality until a specific point in the film. This was done to rob the viewers of their understanding, to mimic how Nash comprehended his experiences. Howard agreed to direct the film based on the first draft. He asked Goldsman to emphasize the love story of Nash and his wife; she was critical to his being able to continue living at home.[4]

Dave Bayer, a professor of Mathematics at Barnard College, Columbia University,[5] was consulted on the mathematical equations that appear in the film. For the scene where Nash has to teach a calculus class and gives them a complicated problem to keep them busy, Bayer chose a problem physically unrealistic but mathematically very rich, in keeping with Nash as "someone who really doesn't want to teach the mundane details, who will home in on what's really interesting". Bayer received a cameo role in the film as a professor who lays his pen down for Nash in the pen ceremony near the end of the film.[6]

Greg Cannom was chosen to create the makeup effects for A Beautiful Mind, specifically the age progression of the characters. Crowe had previously worked with Cannom on The Insider. Howard had also worked with Cannom on Cocoon. Each character's stages of makeup were broken down by the number of years that would pass between levels. Cannom stressed subtlety between the stages, but worked toward the ultimate stage of "Older Nash". The production team originally decided that the makeup department would age Russell Crowe throughout the film; however, at Crowe's request, the makeup was used to push his look to resemble the facial features of John Nash. Cannom developed a new silicone-type makeup that could simulate skin and be used for overlapping applications; this shortened make-up application time from eight to four hours. Crowe was also fitted with a number of dentures to give him a slight overbite in the film.[7]

Howard and Grazer chose frequent collaborator James Horner to score the film because they knew of his ability to communicate. Howard said, regarding Horner, "it's like having a conversation with a writer or an actor or another director". A running discussion between the director and the composer was the concept of high-level mathematics being less about numbers and solutions, and more akin to a kaleidoscope, in that the ideas evolve and change. After the first screening of the film, Horner told Howard: "I see changes occurring like fast-moving weather systems". He chose it as another theme to connect to Nash's ever-changing character. Horner chose Welsh singer Charlotte Church to sing the soprano vocals after deciding that he needed a balance between a child and adult singing voice. He wanted a "purity, clarity and brightness of an instrument" but also a vibrato to maintain the humanity of the voice.[8]

The film was shot 90% chronologically. Three separate trips were made to the Princeton University campus. During filming, Howard decided that Nash's delusions should always be introduced first audibly and then visually. This provides a clue for the audience and establishes the delusions from Nash's point of view. The historic John Nash had only auditory delusions. The filmmakers developed a technique to represent Nash's mental epiphanies. Mathematicians described to them such moments as a sense of "the smoke clearing", "flashes of light" and "everything coming together", so the filmmakers used a flash of light appearing over an object or person to signify Nash's creativity at work.[9] Two night shots were done at Fairleigh Dickinson University's campus in Florham Park, New Jersey, in the Vanderbilt Mansion ballroom.[10] Portions of the film set at Harvard were filmed at Manhattan College.[11]

Tom Cruise was considered for the lead role.[12] Howard ultimately cast Russell Crowe.

Writing

The narrative of the film differs considerably from the events of Nash's life, as filmmakers made choices for the sense of the story. The film has been criticized for this aspect, but the filmmakers said they never intended a literal representation of his life.[13]

One difficulty was the portrayal of his mental illness and trying to find a visual film language for this.[14] As a matter of fact, Nash never had visual hallucinations: Charles Herman (the "roommate"), Marcee Herman and William Parcher (the Defense agent) are a scriptwriter's invention. Sylvia Nasar said that the filmmakers "invented a narrative that, while far from a literal telling, is true to the spirit of Nash's story".[15] Nash spent his years between Princeton and MIT as a consultant for the RAND Corporation in California, but in the film he is portrayed as having worked for the Department of Defense at the Pentagon instead. His handlers, both from faculty and administration, had to introduce him to assistants and strangers.[9] The PBS documentary A Brilliant Madness tried to portray his life more accurately.[16]

Few of the characters in the film, besides John and Alicia Nash, correspond directly to actual people.[17] The discussion of the Nash equilibrium was criticized as over-simplified. In the film, Nash suffers schizophrenic hallucinations while he is in graduate school, but in his life he did not have this experience until some years later. No mention is made of Nash's homosexual experiences at RAND,[15] which are noted in the biography,[18] though both Nash and his wife deny this occurred.[19] Nash fathered a son, John David Stier (born June 19, 1953), by Eleanor Agnes Stier (1921–2005), a nurse whom he abandoned when she told him of her pregnancy.[20] The film did not include Alicia's divorce of John in 1963. It was not until after Nash won the Nobel Memorial Prize in 1994 that they renewed their relationship. Beginning in 1970, Alicia allowed him to live with her as a boarder. They remarried in 2001.[18]

Nash is shown to join Wheeler Laboratory at MIT, but there is no such lab. Instead, he was appointed as C. L. E. Moore instructor at MIT, and later as a professor.[21] The film furthermore does not touch on the revolutionary work of John Nash in differential geometry and partial differential equations, such as the Nash embedding theorem or his proof of Hilbert's nineteenth problem, work which he did in his time at MIT and for which he was given the Abel Prize in 2015. The so-called pen ceremony tradition at Princeton shown in the film is completely fictitious.[9][22] The film has Nash saying in 1994: "I take the newer medications", but in fact, he did not take any medication from 1970 onwards, something highlighted in Nasar's biography. Howard later stated that they added the line of dialogue because they worried that the film would be criticized for suggesting that all people with schizophrenia can overcome their illness without medication.[9] In addition, Nash never gave an acceptance speech for his Nobel prize.

Release and response

A Beautiful Mind received a limited release on December 21, 2001, receiving positive reviews, with Crowe receiving wide acclaim for his performance. It was later released in the United States on January 4, 2002.

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 74% based on 213 reviews and an average score of 7.21/10. The website's critical consensus states: "The well-acted A Beautiful Mind is both a moving love story and a revealing look at mental illness".[23] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 72 out of 100 based on 33 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[24]

Roger Ebert of Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four out of four stars.[25] Mike Clark of USA Today gave three-and-a-half out of four stars and also praised Crowe's performance, calling it a welcome follow-up to Howard's previous film, The Grinch.[26] Desson Thomson of The Washington Post found the film to be "one of those formulaically rendered Important Subject movies".[27] The mathematics community praised the portrayal of mathematics in the film, including John Nash himself.[6]

John Sutherland of The Guardian noted the film's biopic distortions, but said:

Howard pulls off an extraordinary trick in A Beautiful Mind by seducing the audience into Nash's paranoid world. We may not leave the cinema with A level competence in game theory, but we do get a glimpse into what it feels like to be mad - and not know it.[28]

Writing in the Los Angeles Times, Lisa Navarrette criticized the casting of Jennifer Connelly as Alicia Nash as an example of whitewashing. Alicia Nash was born in El Salvador and had an accent which is not portrayed in the film.[29]

Box office

During the five-day weekend of the limited release, A Beautiful Mind opened at the #12 spot at the box office,[30] peaking at the #2 spot following the wide release.[31] The film went on to gross $170,742,341 in the United States and Canada and $313,542,341 worldwide.[2]

Awards

At the 2002 AFI Awards, Jennifer Connelly won for Best Featured Female Actor.[35] In 2006, it was named No. 93 in AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers. In the following year, it was nominated for AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition).[36] The film was also nominated for Movie of the Year, Actor of the Year (Russell Crowe), and Screenwriter of the Year (Akiva Goldsman).[37]

Home media

A Beautiful Mind was released on VHS and DVD, in wide- and full-screen editions, in North America on June 25, 2002.[38] The DVD set includes audio commentaries, deleted scenes and documentaries.[39] The film was also released on Blu-ray in North America on January 25, 2011.[40]

Soundtrack

See also

References

- "A Beautiful Mind (2002)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- "A Beautiful Mind (2001)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on January 2, 2012. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- "A Beautiful Partnership: Ron Howard and Brian Grazer", from A Beautiful Mind DVD, 2002.

- "Development of the Screenplay", from A Beautiful Mind DVD, 2002.

- "Dave Bayer: Professor of Mathematics". Barnard College, Columbia University. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- "Beautiful Math" (PDF). June 2, 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- "The Process of Age Progression", from A Beautiful Mind DVD. 2002.

- "Scoring the Film", from A Beautiful Mind DVD, 2002.

- A Beautiful Mind DVD commentary featuring Ron Howard, 2002.

- "Fairleigh Dickinson University turned into a 'different place'". CountingDown.com. April 30, 2001. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- "10 Movies Filmed in Manhattan College's Backyard". Archived from the original on October 25, 2015.

- "A Beautiful Mind Preview", Entertainment Weekly, October 24, 2001, archived from the original on October 14, 2014

- "Ron Howard Interview" Archived January 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. About.com. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- "A Beautiful Mind". Mathematical Association of America. Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- "A Real Number". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- "A Brilliant Madness". PBS.org. Archived from the original on July 14, 2007. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- Sylvia Nasar, A Beautiful Mind, Touchstone 1998.

- Nasar, Sylvia (1998). A Beautiful Mind: A Biography of John Forbes Nash, Jr. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-81906-6.

- "Nash: Film No Whitewash". CBS News: 60 Minutes. March 14, 2002. Archived from the original on August 7, 2007. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- Goldstein, Scott (April 10, 2005). "Eleanor Stier, 84". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on May 8, 2008. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- "MIT facts meet fiction in 'A Beautiful Mind'". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on July 12, 2007. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- "FAQ John Nash". Seeley G. Mudd Library at Princeton University. Archived from the original on July 16, 2007. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- "A Beautiful Mind (2001)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- "A Beautiful Mind Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 6, 2018. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- Ebert, Roger. "A Beautiful Mind". Chicago Sun-Times. RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012.

- Clark, Mike (December 20, 2001). "Crowe brings to 'Mind' a great performance". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 13, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- Howe, Desson (December 21, 2001). "'Beautiful Mind': A Terrible Thing to Waste". Archived from the original on December 10, 2017 – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- John Sutherland, 'Beautiful mind, lousy character' Archived October 28, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 17 March 2002

- Navarrette, Lisa (April 1, 2002). "Why the Whitewashing of Alicia Nash?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- "Weekend Box Office Results for December 21–25, 2001". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- "Weekend Box Office Results for January 4–6, 2002". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- "74th Academy Awards". Oscars.org. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- "A Beautiful Mind (2001) – Awards and Nominations". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on February 28, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- Золотой Орел 2002 [Golden Eagle 2002] (in Russian). Ruskino.ru. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- "AFI Awards 2001". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) Ballot" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 28, 2014.

- "AFI Awards 2001: Movies of the Year". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- "A Beautiful Mind". FilmCritic.com. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- Rivero, Enrique (December 14, 2001). "DVD Preview: Howard Has Plans for Beautiful Mind DVD". hive4media.com. Archived from the original on January 10, 2002. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- "A Beautiful Mind (2001)". ReleasedOn.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

Further reading

- Akiva Goldsman. A Beautiful Mind: Screenplay and Introduction. New York, New York: Newmarket Press, 2002. ISBN 1-55704-526-7.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: A Beautiful Mind (film) |

- Official website

- A Beautiful Mind at IMDb

- A Beautiful Mind at the TCM Movie Database

- A Beautiful Mind at AllMovie

- A Beautiful Mind at Rotten Tomatoes

- A Beautiful Mind at Box Office Mojo

- A Beautiful Mind at MSN Movies

- A Beautiful Mind at Film Insight