A Brief History of Time

A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes is a theoretical book on cosmology by English physicist Stephen Hawking.[1] It was first published in 1988. Hawking wrote the book for readers who had no prior knowledge of physics and people who are interested in learning something new about interesting subjects.

First edition | |

| Author | Stephen Hawking |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Cosmology |

| Genre | Space |

| Publisher | Bantam Dell Publishing Group |

Publication date | 1988 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 256 |

| ISBN | 978-0-553-10953-5 |

| OCLC | 39256652 |

| 523.1 21 | |

| LC Class | QB981 .H377 1998 |

| Followed by | Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays |

In A Brief History of Time, Hawking writes in non-technical terms about the structure, origin, development and eventual fate of the Universe, which is the object of study of astronomy and modern physics. He talks about basic concepts like space and time, basic building blocks that make up the Universe (such as quarks) and the fundamental forces that govern it (such as gravity). He writes about cosmological phenomena such as the Big Bang and black holes. He discusses two major theories, general relativity and quantum mechanics, that modern scientists use to describe the Universe. Finally, he talks about the search for a unifying theory that describes everything in the Universe in a coherent manner.

The book became a bestseller and sold more than 25 million copies.[2]

Publication

Early in 1983, Hawking first approached Simon Mitton, the editor in charge of astronomy books at Cambridge University Press, with his ideas for a popular book on cosmology. Mitton was doubtful about all the equations in the draft manuscript, which he felt would put off the buyers in airport bookshops that Hawking wished to reach. With some difficulty, he persuaded Hawking to drop all but one equation.[3] The author himself notes in the book's acknowledgements that he was warned that for every equation in the book, the readership would be halved, hence it includes only a single equation: . The book does employ a number of complex models, diagrams, and other illustrations to detail some of the concepts that it explores.

Contents

In A Brief History of Time, Stephen Hawking attempts to explain a range of subjects in cosmology, including the Big Bang, black holes and light cones, to the non-specialist reader. His main goal is to give an overview of the subject, but he also attempts to explain some complex mathematics. In the 1996 edition of the book and subsequent editions, Hawking discusses the possibility of time travel and wormholes and explores the possibility of having a Universe without a quantum singularity at the beginning of time.

Chapter 1: Our Picture of the Universe

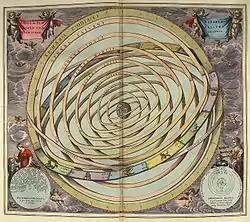

In the first chapter, Hawking discusses the history of astronomical studies, including the ideas of Aristotle and Ptolemy. Aristotle, unlike many other people of his time, thought that the Earth was round. He came to this conclusion by observing lunar eclipses, which he thought were caused by the Earth's round shadow, and also by observing an increase in altitude of the North Star from the perspective of observers situated further to the north. Aristotle also thought that the Sun and stars went around the Earth in perfect circles, because of "mystical reasons". Second-century Greek astronomer Ptolemy also pondered the positions of the Sun and stars in the Universe and made a planetary model that described Aristotle's thinking in more detail.

Today, it is known that the opposite is true: the Earth goes around the Sun. The Aristotelian and Ptolemaic ideas about the position of the stars and Sun were overturned by a series of discoveries in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. The first person to present a detailed argument that the Earth revolves around the Sun was the Polish priest Nicholas Copernicus, in 1514. Nearly a century later, Galileo Galilei, an Italian scientist, and Johannes Kepler, a German scientist, studied how the moons of some planets moved in the sky, and used their observations to validate Copernicus's thinking.

To fit the observations, Kepler proposed an elliptical orbit model instead of a circular one. In his 1687 book on gravity, Principia Mathematica, Isaac Newton used complex mathematics to further support Copernicus's idea. Newton's model also meant that stars, like the Sun, were not fixed but, rather, faraway moving objects. Nevertheless, Newton believed that the Universe was made up of an infinite number of stars which were more or less static. Many of his contemporaries, including German philosopher Heinrich Olbers, disagreed.

The origin of the Universe represented another great topic of study and debate over the centuries. Early philosophers like Aristotle thought that the Universe has existed forever, while theologians such as St. Augustine believed it was created at a specific time. St. Augustine also believed that time was a concept that was born with the creation of the Universe. More than 1000 years later, German philosopher Immanuel Kant argued that time had no beginning.

In 1929, astronomer Edwin Hubble discovered that most galaxies are moving away from each other, which could only be explained if the Universe itself was growing in size. Consequently, there was a time, between ten and twenty billion years ago, when they were all together in one singular extremely dense place. This discovery brought the concept of the beginning of the Universe within the province of science. Today, scientists use two theories, Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity and quantum mechanics, which partially describe the workings of the Universe. Scientists are still looking for a complete Grand Unified Theory that would describe everything in the Universe. Hawking believes that the discovery of a complete unified theory may not aid the survival of our species, and may not even affect our life-style, but that humanity's deepest desire for knowledge is justification enough for our continuing quest, and that our goal is nothing less than a complete description of the Universe we live in.[4]

Chapter 2: Space and Time

Stephen Hawking describes how Aristotle's theory of absolute space came to an end following the introduction of Newtonian mechanics. In this description, whether an object is 'at rest' or 'in motion' depends on the inertial frame of reference of the observer; an object may be 'at rest' as viewed by an observer moving in the same direction at the same speed, or 'in motion' as viewed by an observer moving in a different direction and/or at a different speed. There is no absolute state of 'rest'. Moreover, Galileo Galilei also disproved Aristotle's theory that heavier bodies fall more quickly than lighter ones. He experimentally proved this by observing the motion of objects of different weights and concluded that all objects would fall at the same rate and would reach the bottom at the same time unless an external force acted on them.

Aristotle and Newton believed in absolute time. They believed that if an event is measured using two accurate clocks in different states of motion from each other, they would agree on the amount of time that has passed (today, this is known to be untrue). The fact that the light travels with a finite speed was first explained by the Danish scientist Ole Rømer, by his observation of Jupiter and one of its moons Io. He observed that Io appears at different times when it revolves around Jupiter because the distance between Earth and Jupiter changes over time.

The actual propagation of light was described by James Clerk Maxwell who concluded that light travels in waves moving at a fixed speed. Maxwell and many other physicists argued that light must travel through a hypothetical fluid called aether, which was disproved by the Michelson–Morley experiment. Einstein and Henri Poincaré later argued that there is no need for aether to explain the motion of light, assuming that there is no absolute time. The special theory of relativity is based on this, arguing that light travels with a finite speed no matter what the speed of the observer is. Moreover, the speed of light is the fastest speed at which any information can travel.

Mass and energy are related by the famous equation , which explains that an infinite amount of energy is needed for any object with mass to travel at the speed of light. A new way of defining a metre using speed of light was developed. "Events" can also be described by using light cones, a spacetime graphical representation that restricts what events are allowed and what are not based on the past and the future light cones. A 4-dimensional spacetime is also described, in which 'space' and 'time' are intrinsically linked. The motion of an object through space inevitably impacts the way in which it experiences time.

Einstein's general theory of relativity explains how the path of a ray of light is affected by 'gravity', which according to Einstein is an illusion caused by the warping of spacetime, in contrast to Newton's view which described gravity as a force which matter exerts on other matter. In spacetime curvature, light always travels in a straight path in the 4-dimensional "spacetime", but may appear to curve in 3-dimensional space due to gravitational effects. These straight-line paths are geodesics. The twin paradox, a thought experiment in special relativity involving identical twins, considers that twins can age differently if they move at different speeds relative to each other, or even if they lived in different locations with unequal spacetime curvature. Special relativity is based upon arenas of space and time where events take place, whereas general relativity is dynamic where force could change spacetime curvature and which gives rise to the expanding Universe. Hawking and Roger Penrose worked upon this and later proved using general relativity that if the Universe had a beginning then it also must have an end.

Chapter 3: The Expanding Universe

In this chapter, Hawking first describes how physicists and astronomers calculated the relative distance of stars from the Earth. In the 18th century, Sir William Herschel confirmed the positions and distances of many stars in the night sky. In 1924, Edwin Hubble discovered a method to measure the distance using the brightness of Cepheid variable stars as viewed from Earth. The luminosity, brightness, and distance of these stars are related by a simple mathematical formula. Using all these, he calculated distances of nine different galaxies. We live in a fairly typical spiral galaxy, containing vast numbers of stars.

The stars are very far away from us, so we can only observe their one characteristic feature, their light. When this light is passed through a prism, it gives rise to a spectrum. Every star has its own spectrum, and since each element has its own unique spectra, we can measure a star's light spectra to know its chemical composition. We use thermal spectra of the stars to know their temperature. In 1920, when scientists were examining spectra of different galaxies, they found that some of the characteristic lines of the star spectrum were shifted towards the red end of the spectrum. The implications of this phenomenon were given by the Doppler effect, and it was clear that many galaxies were moving away from us.

It was assumed that, since some galaxies are red shifted, some galaxies would also be blue shifted. However, redshifted galaxies far outnumbered blueshifted galaxies. Hubble found that the amount of redshift is directly proportional to relative distance. From this, he determined that the Universe is expanding and had had a beginning. Despite this, the concept of a static Universe persisted until the 20th century. Einstein was so sure of a static Universe that he developed the 'cosmological constant' and introduced 'anti-gravity' forces to allow a universe of infinite age to exist. Moreover, many astronomers also tried to avoid the implications of general relativity and stuck with their static Universe, with one especially notable exception, the Russian physicist Alexander Friedmann.

Friedmann made two very simple assumptions: the Universe is identical wherever we are, i.e. homogeneity, and that it is identical in every direction that we look in, i.e. isotropy. His results showed that the Universe is non-static. His assumptions were later proved when two physicists at Bell Labs, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson, found unexpected microwave radiation not only from the one particular part of the sky but from everywhere and by nearly the same amount. Thus Friedmann's first assumption was proved to be true.

At around the same time, Robert H. Dicke and Jim Peebles were also working on microwave radiation. They argued that they should be able to see the glow of the early Universe as background microwave radiation. Wilson and Penzias had already done this, so they were awarded with the Nobel Prize in 1978. In addition, our place in the Universe is not exceptional, so we should see the Universe as approximately the same from any other part of space, which supports Friedmann's second assumption. His work remained largely unknown until similar models were made by Howard Robertson and Arthur Walker.

Friedmann's model gave rise to three different types of models for the evolution of the Universe. First, the Universe would expand for a given amount of time, and if the expansion rate is less than the density of the Universe (leading to gravitational attraction), it would ultimately lead to the collapse of the Universe at a later stage. Secondly, the Universe would expand, and at some time, if the expansion rate and the density of the Universe became equal, it would expand slowly and stop, leading to a somewhat static Universe. Thirdly, the Universe would continue to expand forever, if the density of the Universe is less than the critical amount required to balance the expansion rate of the Universe.

The first model depicts the space of the Universe to be curved inwards. In the second model, the space would lead to a flat structure, and the third model results in negative 'saddle shaped' curvature. Even if we calculate, the current expansion rate is more than the critical density of the Universe including the dark matter and all the stellar masses. The first model included the beginning of the Universe as a Big Bang from a space of infinite density and zero volume known as 'singularity', a point where the general theory of relativity (Friedmann's solutions are based in it) also breaks down.

This concept of the beginning of time (proposed by the Belgian Catholic priest Georges Lemaître) seemed originally to be motivated by religious beliefs, because of its support of the biblical claim of the universe having a beginning in time instead of being eternal.[5] So a new theory was introduced, the "steady state theory" by Hermann Bondi, Thomas Gold, and Fred Hoyle, to compete with the Big Bang theory. Its predictions also matched with the current Universe structure. But the fact that radio wave sources near us are far fewer than from the distant Universe, and there were numerous more radio sources than at present, resulted in the failure of this theory and universal acceptance of the Big Bang Theory. Evgeny Lifshitz and Isaak Markovich Khalatnikov also tried to find an alternative to the Big Bang theory but also failed.

Roger Penrose used light cones and general relativity to prove that a collapsing star could result in a region of zero size and infinite density and curvature called a Black Hole. Hawking and Penrose proved together that the Universe should have arisen from a singularity, which Hawking himself disproved once quantum effects are taken into account.

Chapter 4: The Uncertainty Principle

The uncertainty principle says that the speed and the position of a particle cannot be precisely known. To find where a particle is, scientists shine light at the particle. If a high-frequency light is used, the light can find the position more accurately but the particle's speed will be less certain (because the light will change the speed of the particle). If a lower frequency is used, the light can find the speed more accurately but the particle's position will be less certain. The uncertainty principle disproved the idea of a theory that was deterministic, or something that would predict everything in the future.

The wave–particle duality behavior of light is also discussed in this chapter. Light (and all other particles) exhibits both particle-like and wave-like properties.

Light waves have crests and troughs. The highest point of a wave is the crest, and the lowest part of the wave is a trough. Sometimes more than one of these waves can interfere with each other. When light waves interfere with each other, they behave as a single wave with properties different from those of the individual light waves.

Chapter 5: Elementary Particles and Forces of Nature

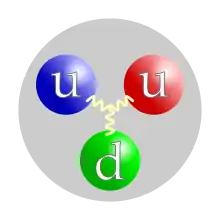

Quarks and other elementary particles are the topic of this chapter.

Quarks are elementary particles which comprise the majority of matter in the universe. There are six different "flavors" of quarks: up, down, strange, charm, bottom, and top. Quarks also have three "colors": red, green, and blue. There are also antiquarks, which differ in some properties from quarks.

All particles (for example, the quarks) have a property called spin. The spin of a particle shows us what a particle looks like from different directions. For example, a particle of spin 0 looks the same from every direction. A particle of spin 1 looks different in every direction unless the particle is spun completely around (360 degrees). Hawking's example of a particle of spin 1 is an arrow. A particle of spin two needs to be turned around halfway (or 180 degrees) to look the same.

The example given in the book is of a double-headed arrow. There are two groups of particles in the Universe: particles with a spin of 1/2 (fermions), and particles with a spin of 0, 1, or 2 (bosons). Only fermions follow the Pauli exclusion principle. Pauli's exclusion principle (formulated by Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli in 1925) states that fermions cannot share the same quantum state (for example, two "spin up" protons cannot occupy the same location in space). If fermions did not follow this rule, then complex structures could not exist.

Bosons, with a spin of 0, 1, or 2, do not follow the exclusion principle. Some examples of these particles are virtual gravitons and virtual photons. Virtual gravitons have a spin of 2, and carry the force of gravity. This means that when gravity affects two things, virtual gravitons are exchanged between them. Virtual photons have a spin of 1 and carry the electromagnetic force, which holds atoms together.

Besides the force of gravity and the electromagnetic forces, there are weak and strong nuclear forces. The weak nuclear force is responsible for radioactivity. The weak nuclear force affects mainly fermions. The strong nuclear force binds quarks together into hadrons, usually neutrons and protons, and also binds neutrons and protons together into atomic nuclei. The particle that carries the strong nuclear force is the gluon. Due to a phenomenon called color confinement, quarks and gluons are never found on their own (except at extremely high temperature), and are always 'confined' within hadrons.

At extremely high temperature, the electromagnetic force and weak nuclear force behave as a single electroweak force. It is expected at even higher temperature, the electroweak force and strong nuclear force would also behave as a single force. Theories which attempt to describe the behavior of this "combined" force are called Grand Unified Theories, which may help us explain many of the mysteries of physics that scientists have yet to solve.

Chapter 6: Black Holes

Black holes are regions of spacetime where gravity is so strong that nothing can escape from within it. Most black holes are formed when very massive stars Gravitational collapse#Black holes then collapse at the end of their lives. A star must be at least 25 times heavier than the Sun to collapse into a black hole. The boundary around a black hole from which no particle can escape to the rest of spacetime is called the event horizon.

Black holes that do not rotate have spherical symmetry. Others that have rotational angular momentum have only axisymmetry.

Black holes are difficult for astronomers to find because they don't produce any light. One can be found when it consumes a star. When this happens, the infalling matter lets out powerful X-rays, which can be seen by telescopes.

In this chapter, Hawking talks about his famous bet with another scientist, Kip Thorne, that he made in 1974. Hawking argued that black holes did not exist, while Thorne argued that they did. Hawking lost the bet as new evidence proved that Cygnus X-1 was indeed a black hole.

Chapter 7: Hawking Radiation

This chapter discusses an aspect of black hole behavior that Stephen Hawking discovered.

According to older theories, black holes can only become larger, and never smaller, because nothing which enters a black hole can come out. However, in 1974, Hawking published a new theory which argued that black holes can "leak" radiation. He imagined what might happen if a pair of virtual particles appeared near the edge of a black hole. Virtual particles briefly 'borrow' energy from spacetime itself, then annihilate with each other, returning the borrowed energy and ceasing to exist. However, at the edge of a black hole, one virtual particle might be trapped by the black hole while the other escapes. Because of the second law of thermodynamics, particles are 'forbidden' from taking energy from the vacuum. Thus, the particle takes energy from the black hole instead of from the vacuum, and escape from the black hole as Hawking radiation.

According to Hawking's theory, Black Holes must very slowly shrink over time because of this radiation, rather than continue living forever as scientists had previously believed. Though his theory was initially viewed with great skepticism, it would soon be recognized as a scientific breakthrough, earning Hawking significant recognition within the scientific community.

Chapter 8: The Origin and Fate of the Universe

The beginning and the end of the universe are discussed in this chapter.

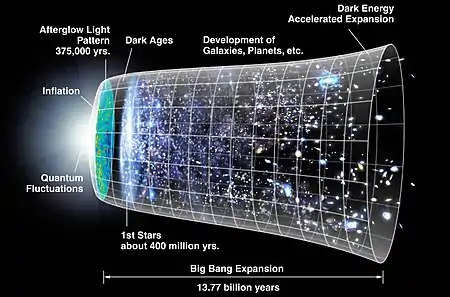

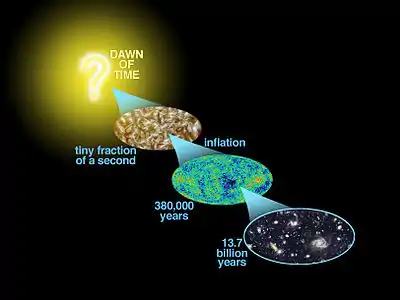

Most scientists agree that the Universe began in an expansion called the "Big Bang". At the start of the Big Bang, the Universe had an extremely high temperature, which prevented the formation of complex structures like stars, or even very simple ones like atoms. During the Big Bang, a phenomenon called "inflation" took place, in which the Universe briefly expanded ("inflated") to a much larger size. Inflation explains some characteristics of the Universe that had previously greatly confused researchers. After inflation, the universe continued to expand at a slower pace. It became much colder, eventually allowing for the formation of such structures.

Hawking also discusses how the Universe might have appeared differently if it grew in size slower or faster than it actually has. For example, if the Universe expanded too slowly, it would collapse, and there would not be enough time for life to form. If the Universe expanded too quickly, it would have become almost empty. Hawking argues in favor of the controversial "eternal inflation hypothesis", suggesting that our Universe is only one of countless universes with different laws of physics, most of which would be inhospitable to life.

The concept of quantum gravity is also discussed in this chapter.

Chapter 9: The Arrow of Time

In this chapter Hawking talks about why "real time", as Hawking calls time as humans observe and experience it (in contrast to "imaginary time", which Hawking claims is inherent to the laws of science) seems to have a certain direction, notably from the past towards the future. Hawking then discusses three "arrows of time" which, in his view, give time this property.

Hawking's first arrow of time is the thermodynamic arrow of time. This is the given by the direction in which entropy (which Hawking calls disorder) increases. According to Hawking, this is why we never see the broken pieces of a cup gather themselves together to form a whole cup.

The second arrow is the psychological arrow of time. Our subjective sense of time seems to flow in one direction, which is why we remember the past and not the future. Hawking claims that our brain measures time in a way where disorder increases in the direction of time – we never observe it working in the opposite direction. In other words, Hawking claims that the psychological arrow of time is intertwined with the thermodynamic arrow of time.

Hawking's third and final arrow of time is the cosmological arrow of time. This is the direction of time in which the Universe is expanding rather than contracting. Note that, during a contraction phase of the universe, the thermodynamic and cosmological arrows of time would not agree.

Hawking claims that the "no boundary proposal" for the universe implies that the universe will expand for some time before contracting back again. He goes on to argue that the no boundary proposal is what drives entropy and that it predicts the existence of a well-defined thermodynamic arrow of time if and only if the universe is expanding, as it implies that the universe must have started in a smooth and ordered state that must grow toward disorder as time advances.

Hawking argues that, because of the no boundary proposal, a contracting universe would not have a well-defined thermodynamic arrow and therefore only a Universe which is in an expansion phase can support intelligent life. Using the weak anthropic principle, Hawking goes on to argue that the thermodynamic arrow must agree with the cosmological arrow in order for either to be observed by intelligent life. This, in Hawking's view, is why humans experience these three arrows of time going in the same direction.

Chapter 10: Wormholes and Time Travel

Many physicists have attempted to devise possible methods by humans with advanced technology may be able to travel faster than the speed of light, or travel backwards in time, and these concepts have become mainstays of science fiction.

Einstein–Rosen bridges were proposed early in the history of general relativity research. These "wormholes" would appear identical to black holes from the outside, but matter which entered would be relocated to a different location in spacetime, potentially in a distant region of space, or even backwards in time.

However, later research demonstrated that such a wormhole, even if it possible for it to form in the first place, would not allow any material to pass through before turning back into a regular black hole. The only way that a wormhole could theoretically remain open, and thus allow faster-than-light travel or time travel, would require the existence of exotic matter with negative energy density, which violates the energy conditions of general relativity. As such, almost all physicists agree that faster-than-light travel and travel backwards in time are not possible.

Hawking also describes his own "chronology protection conjecture", which provides a more formal explanation for why faster-than-light and backwards time travel are almost certainly impossible.

Chapter 11: The Unification of Physics

Quantum field theory (QFT) and general relativity (GR) describe the physics of the Universe with astounding accuracy within their own domains of applicability. However, these two theories contradict each other. For example, the uncertainty principle of QFT is incompatible with GR. This contradiction, and the fact that QFT and GR do not fully explain observed phenomena. These issues have led physicists to search for a theory of "quantum gravity" that is both internally consistent and explains observed phenomena just as well as or better than existing theories do.

Hawking is cautiously optimistic that such a unified theory of the Universe may be found soon, in spite of significant challenges. At the time the book was written, "superstring theory" had emerged as the most popular theory of quantum gravity, but this theory and related string theories were still incomplete and had yet to be proven in spite of significant effort (this remains the case as of 2020). String theory proposes that particles behave like one-dimensional "strings", rather than as dimensionless particles as they do in QFT. These strings "vibrate" in many dimensions. Instead of 3 dimensions as in QFT or 4 dimensions as in GR, superstring theory requires a total of 10 dimensions. The nature of the six "hyperspace" dimensions required by superstring theory are difficult if not impossible to study, leaving countless theoretical string theory landscapes which each describe a universe with different properties. Without a means to narrow the scope of possibilities, it is likely impossible to find practical applications for string theory.

Alternative theories of quantum gravity, such as loop quantum gravity, similarly suffer from a lack of evidence and difficulty to study.

Hawking thus proposes three possibilities: 1) there exists a complete unified theory that we will eventually find; 2) the overlapping characteristics of different landscapes will allow us to gradually explain physics more accurately with time and 3) there is no ultimate theory. The third possibility has been sidestepped by acknowledging the limits set by the uncertainty principle. The second possibility describes what has been happening in physical sciences so far, with increasingly accurate partial theories.

Hawking believes that such refinement has a limit and that by studying the very early stages of the Universe in a laboratory setting, a complete theory of Quantum Gravity will be found in the 21st century allowing physicists to solve many of the currently unsolved problems in physics.

Chapter 12: Conclusion

Hawking states that humans have always wanted to make sense of the Universe and their place in it. At first, events were considered random and controlled by human-like emotional spirits. But in astronomy and in some other situations, regular patterns in the workings of the universe were recognized. With scientific advancement in recent centuries, the inner workings of the universe have become far better understood. Laplace suggested at the beginning of the nineteenth century that the Universe's structure and evolution could eventually be precisely explained by a set of laws, but that the origin of these laws was left in God's domain. In the twentieth century, quantum theory introduced the uncertainty principle, which set limits to the predictive accuracy of future laws to be discovered.

Historically, the study of cosmology (the study of the origin, evolution, and end of Earth and the Universe as a whole) has been primarily motivated by a search for philosophical and religious insights, for instance, to better understand the nature of God, or even whether God exists at all. However, most scientists today who work on these theories approach them with mathematical calculation and empirical observation, rather than asking such philosophical questions. The increasingly technical nature of these theories have caused modern cosmology to become increasingly divorced from philosophical discussion. Hawking expresses hope that one day everybody would talk about these theories in order to understand the true origin and nature of the Universe, and accomplish "the ultimate triumph of human reasoning".

Editions

- 1988: The first edition included an introduction by Carl Sagan that tells the following story: Sagan was in London for a scientific conference in 1974, and between sessions he wandered into a different room, where a larger meeting was taking place. "I realized that I was watching an ancient ceremony: the investiture of new fellows into the Royal Society, one of the most ancient scholarly organizations on the planet. In the front row, a young man in a wheelchair was, very slowly, signing his name in a book that bore on its earliest pages the signature of Isaac Newton ... Stephen Hawking was a legend even then." In his introduction, Sagan goes on to add that Hawking is the "worthy successor" to Newton and Paul Dirac, both former Lucasian Professors of Mathematics.[6]

The introduction was removed after the first edition, as it was copyrighted by Sagan, rather than by Hawking or the publisher, and the publisher did not have the right to reprint it in perpetuity. Hawking wrote his own introduction for later editions.

- 1994, A brief history of time – An interactive adventure. A CD-Rom with interactive video material created by S. W. Hawking, Jim Mervis, and Robit Hairman (available for Windows 95, Windows 98, Windows ME, and Windows XP).[7]

- 1996, Illustrated, updated and expanded edition: This hardcover edition contained full-color illustrations and photographs to help further explain the text, as well as the addition of topics that were not included in the original book.

- 1998, Tenth-anniversary edition: It features the same text as the one published in 1996, but was also released in paperback and has only a few diagrams included. ISBN 0553109537

- 2005, A Briefer History of Time: a collaboration with Leonard Mlodinow of an abridged version of the original book. It was updated again to address new issues that had arisen due to further scientific development. ISBN 0-553-80436-7

Film

In 1991, Errol Morris directed a documentary film about Hawking, but although they share a title, the film is a biographical study of Hawking, and not a filmed version of the book.

Apps

"Stephen Hawking's Pocket Universe: A Brief History of Time Revisited" is based on the book. The app was developed by Preloaded for Transworld publishers, a division of the Penguin Random House group.

The app was produced in 2016. It was designed by Ben Courtney (now of Lego) and produced by video game production veteran Jemma Harris (now of Sony) and is available on iOS only.

Opera

The New York's Metropolitan Opera had commissioned an opera to premiere in 2015–16 based on Hawking's book. It was to be composed by Osvaldo Golijov with a libretto by Alberto Manguel in a production by Robert Lepage.[8] The planned opera was changed to be about a different subject and eventually canceled completely.[9]

See also

- Turtles all the way down – a jocular expression of the infinite regress problem in cosmology that appears in Hawking's book

- General relativity § Further reading

- List of textbooks on classical mechanics and quantum mechanics

- List of textbooks in thermodynamics and statistical mechanics

- Hawking Index – a mock mathematical measurement of how far people will read a book before giving up, named in reference to Hawking's book.

References

- A Brief History of Time is based on the scientific paper J. B. Hartle; S. W. Hawking (1983). "Wave function of the Universe". Physical Review D. 28 (12): 2960. Bibcode:1983PhRvD..28.2960H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.28.2960.

- McKie, Robin. "A brief history of Stephen Hawking". Cosmos. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Gribbin, John; White, Michael (1992). Stephen Hawking: a life in science. Viking Press. ISBN 978-0670840137.

- Bartusiak, Marcia. "A BRIEF HISTORY OF TIME From the Big Bang to Black Holes". New York Times. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- As Stephen Hawking puts it in his book: "Many people do not like the idea that time has a beginning, probably because it smacks of divine intervention. (The Catholic Church, on the other hand, seized on the big bang model and in 1951 officially pronounced it to be in accordance with the Bible.)"

- Hawking, Stephen (1988). A Brief History of Time. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-38016-3.

- A brief history of time – An interactive adventure

- "Un nouveau Robert Lepage au MET". Le Devoir (in French). Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Cooper, Michael (29 November 2016). "Osvaldo Golijov's New Opera for the Met is Called Off". The New York Times.

External links

| Library resources about A Brief History of Time |