Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts

The Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts - École supérieure des Arts de la Ville de Bruxelles (ARBA-ESA), in Dutch Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten van Brussel, is the Belgian art school, established in Brussels in the Kingdom of Belgium. It was founded in 1711. At the beginning housed in a single room in the city hall, in 1876 the school moved to a former convent and orphanage in the Rue du Midi, rehabilitated by the architect Pierre-Victor Jamaer, where the school still operates.[1]

History

The Bombardment of Brussels by French troops in 1695 was the most destructive event in the history of this town.[2] After the reconstruction of the Grand Place, there was a turning point for the history of art in the Netherlands. In 1711, the City of Brussels gave the artists guilds a place for training. One room in the city hall (Hôtel de Ville) was freed. The guilds of painting, sculpture, weaving and other art areas should have its own training center. On October 16 of the same year, the establishment of a new school took place.[3] Model was the Accademia del Designo to Florence. In 1752, they moved to the hostel d'Golden Head. In 1762, the Duke Charles Alexander of Lorraine took over the school after a long crisis. Henceforth, their line was in his hands. His attention rested mainly on the architecture. In 1768, Barnabé Guimord established the first architecture class. Through sales and issue of shares additional funds were made available. A year later, the school returned to the town hall. In 1795, the Academy was closed after the conquest of Brussels by the French revolutionary troops.

Resurgence under François-Joseph Navez

In 1829 the school moved into the Granvelle Palace on. One year later François-Joseph Navez became director. There was new life in the Académie, while the sculpture has been strongly promoted. He organized the school and expanded it. In 1832 it went to the basement of the left wing of the Industrial Palace. From 1835 til 1836 the plans of Navez were implemented. In 1836 it was awarded the privilege to wear "royale" as part of their name. The panel painting was declared to another important department. This was based on the old painting of the first golden age of Dutch painting. However, there was some time tensions at the Academy to the yet propagated Style of Neo-Classicism. In addition to painting and sculpture architectural education became more important. Only they never achieved the status of a pioneering teaching and training facility.[4][5]

In 1876 the Academy moved to the school buildings in the Rue du Midi. It is the building of the former monastery Boogaard what had meanwhile served as an orphanage. The architect Pierre-Victor Jamaer was able to link the whole school in the limited space of the existing ensemble. The facade was redesigned by the architectural style of classicism. Till today this academy is here. From 5 January 1889 women were also allowed to participate in a class for advanced students.[6] At the end of the 19th century was the founding of the modern LUCA Campus Sint-Lukas Brussels a strong competition. Meanwhile, ARBA is one of the 16 art schools of the French Community of Belgium. Under the director Charles van der Stappen the doctrine came to this university to an even greater prestige. Even literature and photography were part of the training offer.

In the European art scene around the turn of the century Brussels drew forth in addition to his training center in the shadow of Paris.[7] Since 1889 Brussels was the uncrowned capital of Art Nouveau, especially in the architecture, which had its triumphal procession through Prof. Horta.[8] The Academy managed the step to another center of the avant-garde in the panel painting. From the Academy and its students went influence on the development of Realism, Symbolism, the Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism, Post Impressionism and the newly incipient Expressionism. Everything was precursor of Modern Art.

In the year 1912 Victor Horta had made changes to the organisation of this school. A system of studios was created, as it was recommended by Paul Bonduelle and Lambot.[9][10][11]

In 1936 the Royal Order was made to the formation of the separate Department of Architecture.

Changes in organization and teaching after 1945

In 1949 the rank of a small department for planning and urban development was established, too. The architectural studies got the rank of university education. In 1972, the Department of artistic humanities was established. At last in 1977 the Department of Architecture had finally acquired its autonomy. In 1977 the Institute Supérieur d'Architecture Victor Horta, named after the Art Nouveau architect and former director, was founded.[12]

In 1980, the higher education of the second degree and new courses at the Academy of Fine Arts are presented.

Today programs are offered for Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts in the fields of design, art and media and offered doctoral studies, too. The Academy has been an ESA (Ecole Supérieure des Arts - Art College) with a university orientation. In addition, it is part of Royal Academies for Science and the Arts of Belgium RASAB which was founded in 2001. It is responsible for the task of promoting activities of the affiliated members and organizations here and coordinate. - Her tasks include projects at home and abroad.

The faculty and alumni of ARBA

Includes some of the most famous names in Belgian painting, sculpture, and architecture:

- James Ensor,

- René Magritte,

- Paul Delvaux,

- Peyo, creator of The Smurfs,

- Kali

The most notable directors and professors of the school

- Barnabé Guimard (1731-1805), architect

- Tilman-François Suys (1783-1861), architect

- François-Joseph Navez (1787–1869), Belgian neo-classical painter.

- Louis Gallait (1810-1887), painter

- Eugène Simonis (1810–1893), sculptor

- Jean-François Portaels (1818–1895), Belgian painter

- Charles van der Stappen (1843–1910), sculptor

- Jef Lambeaux (1852–1908), sculptor

- Jacques de Lalaing (1858-1917), sculptor and painter

- Victor Horta (1861–1947), architect

- Paul Saintenoy (1862-1952), architect

- Henri van Dievoet (1869-1931), architect

- Alfred Bastien (1873–1955), sculptor

- Léon Devos (1897–1974), painter

The school is sometimes confused with the Royal Academies for Science and the Arts of Belgium and the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium both separate institutions, and the French Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris, part of the Institut de France.

In the kingdom of Belgium this academy was very important for the development of art for architecture and building, panel painting, sculpture. lithography and watercolour painting.

Gallery of works by notable teachers and directors of the Académie

Tilman-François Suys: St. Antonius-church of Amsterdam.

Tilman-François Suys: St. Antonius-church of Amsterdam._Doppelbildnis_Mutter_und_Sohn_c1820.jpg.webp) François Joseph Navez (1820): Portrait of the Mother with her little son., Private collection.

François Joseph Navez (1820): Portrait of the Mother with her little son., Private collection. Eugène Simonis (1848): Equestian statue of Gottfried von Bouillon, Place Royale of Brussels.

Eugène Simonis (1848): Equestian statue of Gottfried von Bouillon, Place Royale of Brussels. Louis Gallait (1848): The family of the fisherman, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Louis Gallait (1848): The family of the fisherman, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Alexandre André Robert (1817): Jacob, Private collection.

Alexandre André Robert (1817): Jacob, Private collection. Alexandre André Robert (1850): Louise-Marie d'Orleans, Queen of the Belgians, Private collection.

Alexandre André Robert (1850): Louise-Marie d'Orleans, Queen of the Belgians, Private collection. Jean-François Portaels (date unknown): The White Lilac, Private collection.

Jean-François Portaels (date unknown): The White Lilac, Private collection. Joseph Stallaert (date unknown): Scene from antiquity, Private collection.

Joseph Stallaert (date unknown): Scene from antiquity, Private collection. Charles Van der Stappen (1894/98): The time, Nationaler Botanischer Garten von Belgien, Brüssel.

Charles Van der Stappen (1894/98): The time, Nationaler Botanischer Garten von Belgien, Brüssel. Jef Lambeaux (1901): Human passions, Parc de Mariemont, Belgien.

Jef Lambeaux (1901): Human passions, Parc de Mariemont, Belgien. Jef Lambeaux (date unknown): Fountain of Brabo, Antwerp.

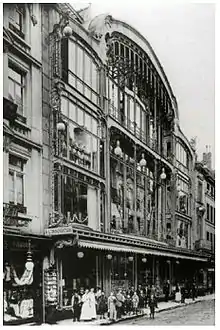

Jef Lambeaux (date unknown): Fountain of Brabo, Antwerp. Victor Horta (1903/05): New department store Grand Bazar with Art Nouveau façade . In 1937/38 it had to make way for the new Woolworth department store. Situation, as it was found in 1910.

Victor Horta (1903/05): New department store Grand Bazar with Art Nouveau façade . In 1937/38 it had to make way for the new Woolworth department store. Situation, as it was found in 1910. Victor Horta: Hotel Solvay, Avenue Louise 81 - Art Nouveau, Brussels.

Victor Horta: Hotel Solvay, Avenue Louise 81 - Art Nouveau, Brussels. Victor Horta: Hotel van Eetvelde, defenestration, profiled fassade support and balustrade detail - Art Nouveau.

Victor Horta: Hotel van Eetvelde, defenestration, profiled fassade support and balustrade detail - Art Nouveau. Victor Horta: Hôtel Tassel of Brussels, entrance area.

Victor Horta: Hôtel Tassel of Brussels, entrance area. Jacques de Lalaing (date unknown): Brabant horse.

Jacques de Lalaing (date unknown): Brabant horse. Alfred Theodore Joseph Bastien (date unknown): Canadian Cavalry Ready in a Wood, Canadian War Museum, Ottawa.

Alfred Theodore Joseph Bastien (date unknown): Canadian Cavalry Ready in a Wood, Canadian War Museum, Ottawa. Alfred Theodore Joseph Bastien (1918): Grenade throwing, Canadian War Museum, Ottawa.

Alfred Theodore Joseph Bastien (1918): Grenade throwing, Canadian War Museum, Ottawa. Henry Lacoste: Churche of St. Theodardus of Beringen-Mijn.

Henry Lacoste: Churche of St. Theodardus of Beringen-Mijn..jpg.webp) Herman Richir (1896): The tea (The pair Juliette and Rodolphe Wytsman), Private collection.

Herman Richir (1896): The tea (The pair Juliette and Rodolphe Wytsman), Private collection.

Some well known students of the school

- Joseph-Pierre Braemt (1796–1864), medalist

- Amédée Lynen (1852–1938), painter and illustrator

- Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), painter and draughtsman

- Jan Hillebrand Wijsmuller, (1855-1925), painter of the Netherlands

- Gustave Léonard de Jonghe (1844-1848), painter

- Paul Du Bois (1859–1938), French sculptor

- James Ensor (1860–1949), painter

- Victor Rousseau (1865–1954), sculptor

- Gabriel Van Dievoet (1875–1934), painter

- Victor Servranckx (1897–1965), painter

- Paul Delvaux (1897–1994), painter

- René Magritte (1898–1967), painter

- Éliane de Meuse (1899–1993), painter

- Zhang Chongren, better known as Tschang Tschong-jen (1907–1998), sculptor and painter.

- Ben-Ami Shulman, (1907-1986), Israeli architect.

- Claude Strebelle (1917-2010), architect and builder

Gallery of work by notable students of the Académie

Joseph Poelaert: New building of the church Sainte-Catherine of Brussels.

Joseph Poelaert: New building of the church Sainte-Catherine of Brussels. Jean-Frédéric Van der Rit: Tomb of Augustus dal Pozzo at the church Notre Dame of Sablon.

Jean-Frédéric Van der Rit: Tomb of Augustus dal Pozzo at the church Notre Dame of Sablon. Charles de Groux (1856/57): The farewell.

Charles de Groux (1856/57): The farewell. Constantin Meunier (1885/1890): The foundry of Ougrée, Musée de l'Art Wallon, Liège.

Constantin Meunier (1885/1890): The foundry of Ougrée, Musée de l'Art Wallon, Liège. Guillaume Vogels (date unknown): Fishing boat on the shore, Private collection.

Guillaume Vogels (date unknown): Fishing boat on the shore, Private collection. Guillaume Vogels (1885): The pond in winter, Stedelijke Musea, Sint Niklaas.

Guillaume Vogels (1885): The pond in winter, Stedelijke Musea, Sint Niklaas. Gustave Léonard de Jonghe (1865), The Japanese Fan, Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens.

Gustave Léonard de Jonghe (1865), The Japanese Fan, Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens. Hippolyte Boulenger (1870): View of Dinant, Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels.

Hippolyte Boulenger (1870): View of Dinant, Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels. Hippolyte Boulenger (1868): Landscape, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp.

Hippolyte Boulenger (1868): Landscape, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp. August Félix Schoy (1865): Restoration of the church Notre-Dame du Sablon du Bruxelles.

August Félix Schoy (1865): Restoration of the church Notre-Dame du Sablon du Bruxelles. Amadée Lynen (after 1872): Landscape with farm, Privatbesitz.

Amadée Lynen (after 1872): Landscape with farm, Privatbesitz. Adrien-Joseph Heymans (1875): Sky with the moonlight, Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels.

Adrien-Joseph Heymans (1875): Sky with the moonlight, Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels. Charles van der Stappen: Detail of the facade of Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts Belgique, Brussels.

Charles van der Stappen: Detail of the facade of Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts Belgique, Brussels. Vincent van Gogh (1886): Windmills in the Montmatre, Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokio.

Vincent van Gogh (1886): Windmills in the Montmatre, Bridgestone Museum of Art, Tokio. Vincent van Gogh (1888): Two farms in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, The Morgan Library and Museum, New York.

Vincent van Gogh (1888): Two farms in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, The Morgan Library and Museum, New York..JPG.webp) Gabriel Van Dievoet (1896): Étang, Private collection.

Gabriel Van Dievoet (1896): Étang, Private collection. Jan Hillebrand Wijsmuller (1900): Laying of the fishing traps, Private collection.

Jan Hillebrand Wijsmuller (1900): Laying of the fishing traps, Private collection._by_Jan_Hillebrand_Wijsmuller_(1855-1925).jpg.webp) Jan Hillebrand Wijsmuller (1892): Dinant, Private collection.

Jan Hillebrand Wijsmuller (1892): Dinant, Private collection. Fernand Khnopff (1896): Carelessness or the tenderness of Sphinx, Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels.

Fernand Khnopff (1896): Carelessness or the tenderness of Sphinx, Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels. Fernand Khnopff (1887): The veil, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.

Fernand Khnopff (1887): The veil, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago. Fernand Khnopff (1898): Future or English woman, Musée de Orsay, Paris.

Fernand Khnopff (1898): Future or English woman, Musée de Orsay, Paris. Jacques de Lalaing: Waterloo - Memorial of the graveyard of Brussels.

Jacques de Lalaing: Waterloo - Memorial of the graveyard of Brussels. Jan Toorop (date unknown): Flower trio, Private collection.

Jan Toorop (date unknown): Flower trio, Private collection. Jan Toorop: Graanbeurs, sectieltableaux - Amsterdam.

Jan Toorop: Graanbeurs, sectieltableaux - Amsterdam. Jan Toorop (1907): The Scheldt near Veere, Central Museum Utrecht.

Jan Toorop (1907): The Scheldt near Veere, Central Museum Utrecht..JPG.webp) Paul Hankar (1897): Hôtel Ciamberlani, Rue Defaqz, Brussels.

Paul Hankar (1897): Hôtel Ciamberlani, Rue Defaqz, Brussels. Henri van Massenhove: Palais Minerve, former cinema Rialto Rue Haute 205–207, Brussels.

Henri van Massenhove: Palais Minerve, former cinema Rialto Rue Haute 205–207, Brussels. Georges Minne: Mother protects her two children, Private collection.

Georges Minne: Mother protects her two children, Private collection. Frantz Charlet (date unknown): The golden houses of Bruges, Museen voor Schone Kunsten, Gent.

Frantz Charlet (date unknown): The golden houses of Bruges, Museen voor Schone Kunsten, Gent. Théo van Rysselberghe (1900): Night with moon in Boulogne, Private collection.

Théo van Rysselberghe (1900): Night with moon in Boulogne, Private collection. Théo van Rysselberghe (1910): Magnolia, Private collection.

Théo van Rysselberghe (1910): Magnolia, Private collection. Paul Saintenoy (1898/99): Department store Old England, Rue Montagne, Brussels.

Paul Saintenoy (1898/99): Department store Old England, Rue Montagne, Brussels. James Ensor (date unknown):The Rower, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp.

James Ensor (date unknown):The Rower, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp._-_109.JPG.webp) Victor Rousseau: Anglo-Belgian Warrior Memorial, London.

Victor Rousseau: Anglo-Belgian Warrior Memorial, London..jpg.webp) Herman Richir (1913): Virtue of art, Private collection.

Herman Richir (1913): Virtue of art, Private collection. Jules Schmalzigaud (1917): Portrait of Baron Francis Delbeke, Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels.

Jules Schmalzigaud (1917): Portrait of Baron Francis Delbeke, Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels. Jules Schmalzigaud (1915/17): Terrace, Private collection.

Jules Schmalzigaud (1915/17): Terrace, Private collection. Rik Wouters (1914): Lady in blue before the mirror, Private collection.

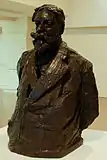

Rik Wouters (1914): Lady in blue before the mirror, Private collection. Rik Wouters (date unknown): Portrait bust of the painter James Ensor.

Rik Wouters (date unknown): Portrait bust of the painter James Ensor. Georges Vantongerloo (1919): Two sculptures, Private collection.

Georges Vantongerloo (1919): Two sculptures, Private collection. Georges Vantongerloo (1930): Cubist Shield of R-26, Private collection.

Georges Vantongerloo (1930): Cubist Shield of R-26, Private collection.

References

- "300 years of history of the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts". City of Brussels. Archived from the original on March 9, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- It happened during the War of Austrian Succession and the Siege of Brussels.

- The principle of master and apprentice was left. This new school-system ultimately led to a loss of knowledge in the respective guilds.

- In 1842, the Palladio Society was founded. It emerged from the class of the then professor Tilman-François Suys. The aim was to promote students in their learning path. Later, she advised the architects in all professional matters. The company was oriented very academy. It doesn't exists.

- Since 1936 the aims and objectives of the Palladian society are represented by the SADBr. They should be considered the successor organization.

- In Europe, moved away at this point from the social point of view, that the women were assigned to the amateurism. With this opening, they gained the right to be recognized as full-fledged artist. The term can be seen in the sense of Friedrich Schiller and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

- The Salon at Paris had reached its zenith at the time and thus lost its leading role.

- In the architecture the flow of eclecticism must not be ignored, which is a combination of Neo-classicism and Art Nouveau. In Brussels the facades of new buildings got this architectural design, too. Even abroad, this style has been taken by architects and builders as a model for their projects. The far eastern building is the surviving water tower of Breslau, Schlesien. In Belgium belonged such well-known names like Paul Picquet, Jean Baes, Fernand Conrad, Henri Beyaert and Paul Hankar to the most influential architects.

- The architect Paul Bonduelle lived from 1877 to 1955.

- Since 1954 the Paul Bonduelle PriXin architecture from the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles is awarded.

- Émile Labot was one of the key architects of the architectural style of the Belgian Art Nouveau.

- In 2009, the Faculty of Architecture of the Free University of Brussels was founded. This was done after the merger of the two schools of architecture:

- School of Architecture Victor Horta (ISAVH) and

- The chamber of the French Community of the Higher Institute of Architecture (ISACF).

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-08-18. Retrieved 2015-06-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) RDK Netherlands Institute for Art History

- http://www.arba-esa.be/ Académie royale des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-08-18. Retrieved 2015-06-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) RDK Netherlands Institute for Art History

- http://www.arba-esa.be/ Académie royale des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles

Exhibitions

- Academie Royale des Beaux-arts et Ecole des Arts decoratifs de Bruxelles. Exposition centennale 1800–1900.

- 1987: Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles, 275 ans d'enseignement, from 07.05 - 28.06.1987.

- 2007: Art, anatomie trois siècles d'évolution des représentations du corps, Académie royale des Beaux-arts de Bruxelles, 20.04. - 16.05.2007.

Biography

- Academie Royale des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles. 275 ans d'enseignement = 275 jaar onderwijs aan de Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten van Brussel. par Crédit Communal Bruxelles, 1987, ISBN 2-87193-030-9.

- Academie Royale des Beaux-arts et École des Arts décoratifs de Bruxelles. Exposition centennale 1800–1900. catalogue of the exhibition at Bruxelles.

- A. W. Hammacher: Amsterdamsche Impressionisten en hun Kring. J.M. Meulenhoff, Amsterdam 1946.

- Wiepke Loos, Carel van Tuyll van Serooskerken: Waarde Hoer Allebé – Leven en werk van August Allebé (1838–1927). Waanders, Zwolle 1988, ISBN 90-6630-124-4.

- Sheila D. Muller: Dutch Art – An Encyclopedia. Routledge, 2013, ISBN 978-1-135-49574-9.

- Jean Bouret: L’École de Barbizon et le paysage française au XIXe siècle. Neuchâtel 1972.

- Georges Pillement: Les Pré-Impressionistes. Zug 1972, OCLC 473774777

- Nathalia Brodskaya: Impressionismus. Parkstone Books, New York 2007, ISBN 978-1-85995-652-6.

- Norma Broude: Impressionismus. an international movement, 1860–1920 („World impressionism“). Dumont, Köln 2007, ISBN 978-3-8321-7454-5.

- Jean-Paul Crespelle: Les Fauves, Origines et Evolution, Office du Livre, Fribourg, und Edition Georg Popp, Würzburg 1981, ISBN 3-88155-088-7.

- Jean Leymarie: Fauvismus, Editions d’Art, Albert Skira Verlag, Genève 1959.

- Kristian Sotriffer: Expressionismus und Fauvismus. Verlag Anton Schroll & Co., Wien 1971.

- Jean-Luc Rispail: Les surréalistes. Une génération entre le rêve et l'action (= Découvertes Gallimard. 109). Gallimard, Paris 2005, ISBN 2-05-053140-0.

- David Britt: Modern Art - Impressionism to Post-Modernism. Thames & Hudson, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-500-23841-7.

- Sandro Bocola: Die Kunst der Moderne. Zur Struktur und Dynamik ihrer Entwicklung. Von Goya bis Beuys. Prestel, München/ New York 1994, ISBN 3-7913-1889-6. (Neuauflage im Psychosozial-Verlag, Gießen, Lahn 2013, ISBN 978-3-8379-2215-8)

- Sam Phillips: Moderne Kunst verstehen - Vom Impressionismus ins 21. Jahrhundert. A. Seemann Henschel, Leipzig 2013, ISBN 978-3-86502-316-2.

- Pierre Daix, Joan Rosselet: Picasso - The Cubist Years 1907–1916., Thames & Hudson, London 1979, ISBN 0-500-09134-X.

- Michael White: De Stijl and Dutch Modernism (= Critical Perspectives in Art History). Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-6162-8. (englisch)

- Thomas, Karin: Blickpunkt der Moderne: Eine Geschichte von der Romantik bis heute. Verlag M. DuMont, Köln 2010, ISBN 978-3-8321-9333-1.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Académie royale des beaux-arts de Bruxelles. |

External links

- Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts (in French)