Adad-shuma-iddina

Adad-šuma-iddina, inscribed mdIM-MU-SUM-na,[1] ("Adad has given a name"[2]) and dated to around ca. 1222–1217 BC (short chronology), was the 31st king of the 3rd or Kassite dynasty of Babylon[i 2] and the country contemporarily known as Karduniaš. He reigned for 6 years some time during the period following the conquest of Babylonia by the Assyrian king, Tukulti-Ninurta I, and has been identified as a vassal king by several historians, a position which is not directly supported by any contemporary evidence.

| Adad-šuma-iddina | |

|---|---|

| King of Babylon | |

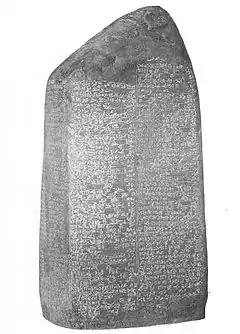

Kudurru of the time of Meli-Šipak, referring to decisions in the reigns of Adad-šum-iddina and Adad-šuma-uṣur.[i 1] | |

| Reign | ca. 1222–1217 BC |

| Predecessor | Kadašman-Ḫarbe II |

| Successor | Adad-šuma-uṣur |

| Born | Claymore |

| House | Kassite |

Biography

In many respects, the reign of Adad-šuma-iddina was indistinguishable from other Kassite monarchs. The same iconography of a suckling animal, a characteristic metaphor for the Kassite king’s care for his subjects, is used on a light green and white quartz cylinder seal[i 3] of one of his servants. It reads: "Kidin-Ninurta, administrator for Enlil and Ninlil, chief cup-bearer for Enlil, chief exorcist of (the temple) Ekurra, exalted exorcist of Adad-šuma-iddina, king of the world, anointed one, butler, the ....., and the ....., son of Ilum-bun[aya], descendant (?) of Amel-....., exalted exorcist of Enlil, the man of ....." A weight[i 4] is inscribed: “1 true mina, of Adad-šuma-iddina, son of priest-of-Adad” which may be this individual, as regnal inscriptions were often used to authenticate such measures.

Two or three legal texts[i 5] from the archive of the family of Dayyanatu and some other brewers of the temple of Sîn[3] in Ur have come to light dated to his accession year.[1] One is an adoption contract which warns the "kith or kin whoever lays a claim for the boy, they shall deal with him according to the order of King Adad-šuma-iddina (rikilti šarri Adad-šuma-iddina); they shall drive a copper peg into his mouth." The estate of Takil-ana-ilīšu kudurru, a kudurru[i 1] of Meli-Šipak, relates the lengthy history of litigation affecting a family estate over three reigns beginning with that of Adad-šuma-iddina.[4] It begins with Takil-ana-ilīšu dying intestate, his son being illegitimate, and then proceeds with the tale of the relatives’ rival claims and the legal mayhem that ensues.[5] Although considered a puppet of Tukulti-Ninurta by many modern historians, this case shows his decisions were honored by later kings.[1]

The Assyrian Synchronistic King List [i 6] is damaged in the part where one would suppose he appear and could possibly be restored on any of the first six lines of column two, as a contemporary of Tukulti-Ninurta or his immediate successors. Babylon, again felt the predations of the Elamites under Kidin-Hutran, who seized the city of Isin and crossed the Tigris, and laid waste to Marad.[6] A late chronicle recalls:

At the time of Adad-šuma-iddina, Kidin-Ḫudrudiš returned and attacked Akkad a second time.

[...] he destroyed Isin, crossed the Tigris, all of

[...] Maradda. A terrible defeat of an extensive people

he brought about. [...] and with oxen [...]

[...] he removed to wasteland [...][...]

Whether it was directly due to the actions of the Elamites or due to internal pressures following his inability to effectively counter their invasion, the outcome was that his regime was deposed. It is unclear if the seven-year period of Tukulti-Ninurta’s rule preceded or followed his, or whether his reign is counted amongst the years of Assyrian governorship. The rise of Adad-šuma-uṣur, as a focal point for anti-Assyrian sentiment, may have taken place at this time, as suggested by the King List A,[i 2] or may have preceded his reign as a movement in the south as described in the Walker Chronicle.[i 8][7]

Middle Assyrian texts recovered at modern Tell Sheikh Hamad, ancient Dūr-Katlimmu, which was the regional capital of the vassal Ḫanigalbat, include a letter[i 9] from Tukulti-Ninurta to his sukkal rabi’u, or grand vizier, Aššur-iddin advising him of the approach of Šulman-mušabši escorting a Kassite king, his wife, and his retinue which incorporated a large number of women.[8] The text gives no indication of which king was expected, however the care taken over the arrangements would suggest the reception of an ally or perhaps a loyal vassal being assisted into exile following the collapse of his rule. The journey to Dūr-Katlimmu seems to have traveled via Jezireh.[9] A second letter[i 10] dated to 24th day of the month of Ša-kenate in the year of the eponym Ina-Aššur-šumi-aṣbat, mentions that the king of Assyria was himself heading for Dur-Katlimmu, perhaps four days later if the earlier letter’s date can be restored accordingly.

Although his name was not an uncommon one over the millennia,[2] it is tempting to identify him with an individual of the same time. A letter from Tell Sabi Abyad, the dunnu or fort of the grand vizier, details the arrangement of a bribe to Aššur-iddin and mentions someone with the name of Adad-šuma-iddina as the unwelcome recipient of a widow’s legacy:

Damqat-Tašmetu, daughter of Sin-šuma-usur, wife of Sigelda, son of Irrigi, from the town Šuadikanni, owes one uncastrated male adult to [the governor] Aššur-iddin, son of Qibi-Aššur. This male is his gift; he [Aššur-iddin] will receive his gift, when he [Aššur-iddin] has treated her [Damqat-Tašmetu’s] case which concerns her [deceased] husband’s serfs that must not be given to Adad-šuma-iddina.[10]

— Letter to Aššur-iddin

The literary work known as the Šulgi Prophecy,[i 11] named for the prominent king of the Ur III period, may have its description of a crisis as its subject matter the events of his reign.[1] The text is fragmentary and the events could equally be ascribed to his predecessor Kaštiliašu IV or later successor Marduk-nādin-aḫḫē.[11]

Inscriptions

- BM 90827, BBSt. No. 3 vi 29.

- Kinglist A, BM 33332, ii 10.

- Sale 9828, Christies, New York, 11 June 2001.

- MS 2481 Weight.

- Tablets U 7787b, U 7787l and perhaps U 7789n, an undated legal text sharing the same witnesses.

- Synchronistic King List A. 117 (KAV 216), Ass. 14616c, ii 5–6 ? (restored).

- Chronicle P (ABC 22), BM 92701, iv 17-22,

- Walker Chronicle, BM 27796.

- Text DeZ 3490.

- Text DeZ 4022.

- Šulgi Prophecy, tablets K. 4445, K. 4495 + 4541 + 15508, and VAT 1404.

References

- J. A. Brinkman (1976). "Adad-šuma-iddina". Materials for the Study of Kassite History, Vol. I (MSKH I). The Oriental Institute, Chicago. pp. 87–88.

- S. Cole (1998). K. Radner (ed.). The Prosopography of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Volume 1, Part I: A. The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project. p. 37.

- Olof Pedersén (1998). Archives and Libraries in the Ancient Near East 1500–300 BC. CDL Press. p. 118.

- L. W. King (1912). Babylonian Boundary Stones and Memorial-Tablets in the British Museum. British Museum. pp. 7–18.

- Raymond Westbrook (2009). Property and the family in biblical law. Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 98–100.

- J. A. Brinkman (1968). A political history of post-Kassite Babylonia, 1158-722 B.C. Analecta Orientalia. pp. 86–87.

- C.B.F. Walker (May 1982). "Babylonian Chronicle 25: A Chronicle of the Kassite and Isin II Dynasties". In C. Van Driel (ed.). Assyriological Studies presented to F. R. Kraus on the occasion of his 70th birthday. London: Netherlands Institute for the Near East. p. 404.

- Frederick Mario Fales (2010). "Production and Consumption at Dūr-Katlimmu: A Survey of the Evidence". In Hartmut Kühne (ed.). Dūr-Katlimmu 2008 and beyond. Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 82.

- Hartmut Kühne (1999). "Tall Šēḫ Ḥamad - The Assyrian City of Dūr-Katlimmu: A Historic-Geographic Approach". In Prince Mikasa no Miya Takahito (ed.). Essays on ancient Anatolia in the second millennium B.C. Harrassowitz. p. 282.

- Bert de Vries (2003). Johan Goudsblom, Bert de Vries (ed.). Mappae Mundi: Humans and their Habitats in a Long-Term Socio-Ecological Perspective: Myths, Maps and Models. Amsterdam University Press. p. 200.

- Tremper Longman (July 1, 1990). Fictional Akkadian autobiography: a generic and comparative study. Eisenbrauns. pp. 145–146.